Story by Jason Christian

Camp Livingston, deep in the Louisiana pines, used to be the site of a World War II Japanese internment camp. Drawing from the memories of internees, the research of two Louisiana State University librarians and other historians, and the activism of survivors and their descendants, this story uncovers a buried piece of American history.

“We are like birds in a cage

Moonlight shines on barbed wire.”

—

Kumaji “Suikei” Furuya, An Internment Odyssey

Kumaji Furuya set his gaze upon a wedge of geese crossing the Louisiana sky. It was October 1942, and unaccustomed to the climate and family separation, the prisoner was in search of ways to temper the pain. To the guards keeping watch, the birds may have meant nothing, but the 53-year-old Japanese man had only ever seen wild geese in books. He later wrote in his memoir, An Internment Odyssey, that they looked motionless and beautiful, a promise of cooler weather, an end to days wasted lying in cool pits dug beneath barrack floors.

Built in 1940 in a clearing of pines, one of a cluster of Army posts in the area, Camp Livingston was installed 12 miles northeast of Alexandria, Louisiana, for the purpose of training entire divisions. After the attacks on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, a portion of Livingston was converted to an internment camp. In June 1942, after a month at Camp Forrest in Tennessee, Furuya transferred to Livingston. He was among dozens of other civilians and a single prisoner of war, Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, who was captured in Hawaii, after the coordinated attack, when his “midget” submarine smashed against coral reefs and sank. (As the war raged on, a few dozen more Japanese POWs came and went.)

For the approximate year, civilians were held in camp — before German and Italian POWs replaced them. They came in waves, arriving by train, more than 1,100 Japanese immigrants (“Issei” in Japanese), who left behind families and communities across the United States.

Furuya didn’t know if he would die in this camp, but he knew he’d committed no treasonous crimes. None of the civilians had, and faced with the enormity of this injustice, some of them barely coped. Some fell into depression and poor health and some died. At least seven, in various camps, were shot and killed. At Fort Sill, in Oklahoma, a fellow Issei from Hawaii, Kanesaburo Oshima, was gunned down for trying to scale a fence. Witnesses said leaving his wife to care for 11 children and a failing business was too much for him to bear. Nobody knew when — or if — this war would end. Rumors that it might last 25 years, perhaps 100 years, prompted some internees to reluctantly volunteer for a prisoner exchange with Japan, a country many hadn’t seen in more than half a lifetime. At least there, they reasoned, they could live outside of the barbed wire.

Aerial view of the 106th Cavalry (Chicago National Guard) encampment at Camp Livingston, Louisiana.

This nightmare began before 353 Imperial Japanese aircraft showered bombs on Pearl Harbor: Dec. 7, 1941. The surprise attack stunned Furuya as much as anyone else. Nevertheless, that afternoon, while his son, an ROTC cadet, defended Farrington High School nearby, two officers hauled Furuya away. He left without a struggle and with only the clothes on his back, assuming the matter would quickly resolve. But it didn’t turn out that way. Unbeknownst to him, Furuya had been placed on the Custodial Detention Index (aka the A-B-C classification matrix), a covert government program established to surveille “aliens” and rank them into three levels of ostensible risk to national security, in case war should break out. Fueled by xenophobia and paranoia, thousands of people were interned based on their ethnic background: “17,447 of Japanese ancestry, 11,507 of German ancestry, 2,730 of Italian ancestry, and 185 others,” writes historian and camp survivor Tetsuden Kashima.

After two hellish months at a makeshift camp at Sand Island, at the mouth of Honolulu Harbor, the federal government finally gave Furuya a kangaroo court. A panel of five men posed questions about his life and loyalty to the United States. Furuya was the founder of the first Japanese radio program in Hawaii, the owner of a successful furniture store, the vice president of the Honolulu Japanese Chamber of Commerce, a published haiku poet, and a beloved leader of his community. He had lived in Hawaii since 1907, the same year the U.S. restricted Japanese immigration to the mainland under the Gentlemen’s Agreement. Furuya’s five children were “Nisei” (second-generation Japanese Americans), U.S. citizens. Furuya and his wife might have become naturalized citizens as well, but the Immigration Act of 1924 prevented it. The panel asked if Furuya had given money to the “Japanese cause,” and he admitted that before the war, he’d “donated about $25” to the families of wounded Japanese soldiers, a gesture interpreted as “pro-Japanese.” His fate was then sealed, and likely already had been. He was reduced to a serial number, officially labeled an “enemy alien.”

Furuya waited around with scores of Issei leaders who had just suffered through the same routine, many of them charged with even less “evidence.” They milled around in silence, fighting bouts of sobs, as fear and racism from the public, the media, and politicians reached a fever pitch. Then, on Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, a vaguely, yet cleverly-worded document which gave the Secretary of War and military commanders power to establish “military areas” and “exclude” from them anyone they deemed a threat to national security. Much of the West Coast was labeled a military area, and of the three Axis powers, most of the effort went into rounding up Japanese immigrants and their descendants and forcing them to live in concentration camps.

The camps we tend to remember were called relocation centers, and they were run by the newly minted War Relocation Authority or WRA. Ten of them dot the map: Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho each had one; California, Arizona, and Arkansas had two. While the WRA camps were featured in Life and made headlines in The New York Times, the 18 camps run by the U.S. Army, Camp Livingston among them, and the others controlled by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), an agency of the Department of Justice (DOJ), remained in relative obscurity. And the whole effort was for naught. “Not a single American of Japanese descent, alien or citizen, [was] charged with espionage or sabotage during the war,” writes Richard Reeves in Infamy: The Shocking Story of the Japanese Internment in World War II. “These men, women, and children were locked up for the duration of the war because they looked like the enemy.”

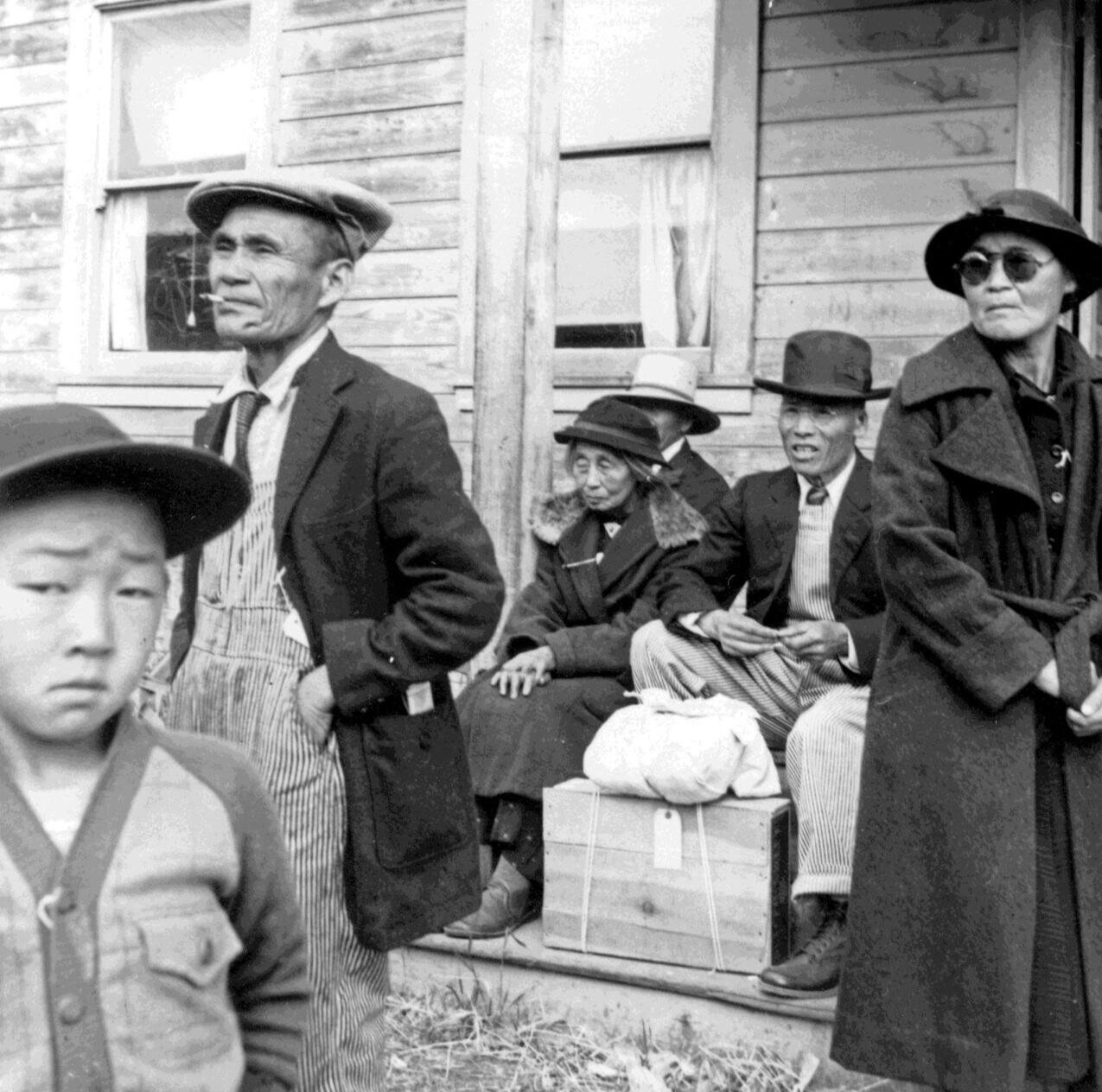

May 9, 1942. Farm families wait for a bus to Tanforan Assembly Center with 595 others from nearby Centerville, California. Photo by Dorothea Lange.

At the end of his administration, President Ronald Reagan passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, an official apology and admission that incarcerating 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — half children, and two-thirds American citizens — was “a grave injustice … motivated by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The federal government gave former internees $20,000 reparation payments and set aside funds for education. In February 2020, California’s state congress apologized for its role in internment as well. And while these measures are certainly important, what the government did to Japanese Americans is hardly understood, and internees from the A-B-C lists rarely enter the conversation.

History, too, has forgotten the more than 2,200 Japanese nationals (and some 3,000 others) ensnared in the Latin American Enemy Alien Control Program, yet another classified operation in which the U.S. made a pact with more than a dozen countries to remove (with the FBI’s help) Japanese, German, and other immigrants from within their borders to be used in prisoner exchanges. Many of the Japanese were taken from Peru, but 10 Panamanian Japanese were held at Livingston, according to Furuya, mostly men in their 20s, with whom he shared a barrack. They arrived via Camp Algiers, a small DOJ camp in New Orleans, notorious for imprisoning “an unlikely contingent of 60 Jewish refugees,” writes Marilyn Miller, a Tulane University professor and author of the forthcoming book, Port of No Return: Enemy Alien Internment in World War II New Orleans. The refugees fled Germany to avoid its death camps, only to be swept up, along with pro-Nazi Germans, and placed in camps in the United States.

The day after Roosevelt issued EO 9066, Furuya boarded the USS Grant steamer bound for the mainland. He would hopscotch from camp to camp (six in total) for four years before returning to Hawaii to rebuild his life. In 1964, under the pen name Suikei Furuya, he published his memoir, Haisho Tenten (An Internment Odyssey), which wasn’t available in English until 2017. “It would please me greatly if my writing helps to enrich the history of the Japanese in Hawaii,” Furuya wrote.

He was looking inward to his community, and there this story is better known. But in Wisconsin, where he stayed for 78 days at Fort McCoy, and in Montana, New Mexico, and Washington — where he was sent after leaving the South — efforts to educate the public are nascent if they exist at all.

“Each story preserved, like a fabled grain of rice, has been guiding us to find our way home to the truth and to the reality of our historical experience.”

—

Satsuki Ina, Keynote Speech at Densho Dinner, November 2019

In 2016, Hayley Johnson, a librarian at Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, Louisiana, watched a video of Muslim-American children reading letters to elderly Japanese American camp survivors, letters written by interned Nisei children during the war. The film, created by Frank Chi, was part of an exhibit at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, drawing connections between historical and current racial oppression in America. At the time, the Syrian Civil War had created a refugee crisis, triggering an outpouring of worldwide sympathy, but also stoking Islamophobic flames. Meanwhile, then-presidential candidate Donald Trump was ramping up his anti-immigrant rhetoric, condemning Muslims and Mexicans, solidifying support based on fear.

Although the video lasted just over two minutes, it moved Johnson immensely and got her thinking about her own backyard. Information was scarce, but she learned people had it wrong: a camp in central Louisiana housed quite a lot of civilians, not only POWs as she had heard all her life. How had the public been so misled? She shared her findings with her colleague and friend, Sarah Simms, and together they scoured the internet and dug up a name: the Koharas, a Japanese American family that ran a photography studio in Alexandria during the war and helped visitors en route to see relatives in the camp. This was a start, but so much was still unknown. What they needed was access to the mother lode of government information: the National Archives. They wrote some grants, sent them off, and the news soon arrived; they would get their funding through the American Library Association. In the spring of 2017, the two librarians flew to Washington, D.C. This was more than a passing curiosity. There would be no turning back.

***

Before COVID-19 destroyed our sense of normalcy, before average Americans could enter public spaces without fear of getting sick, I spoke with Johnson and Simms in a conference room inside the cloistered inner sanctum of Troy H. Middleton Library at Louisiana State University, where they now work. (Last summer, Middleton’s name was dropped after a long campaign stemming from the former LSU president’s efforts to maintain segregation.) As the women guided me past rows of office cubicles, I noticed a shelf full of unopened bottles of hand sanitizer and wondered if an employee had hoarded them. Life felt more like a “tragedy of the commons” with each passing hour. The university would shut down the next day. Classes would move online. Our world would turn more uncertain overnight.

Johnson and Simms have worked together for years. In their view, a primary goal of librarianship is to gather marginalized histories and voices and make them accessible to the public. Since 2013, they have created, expanded, or hosted traveling collections and exhibits on Muslim Americans, African Americans, and Latinx Americans living across the South. Finding out what really happened at Camp Livingston would be another worthy pursuit.

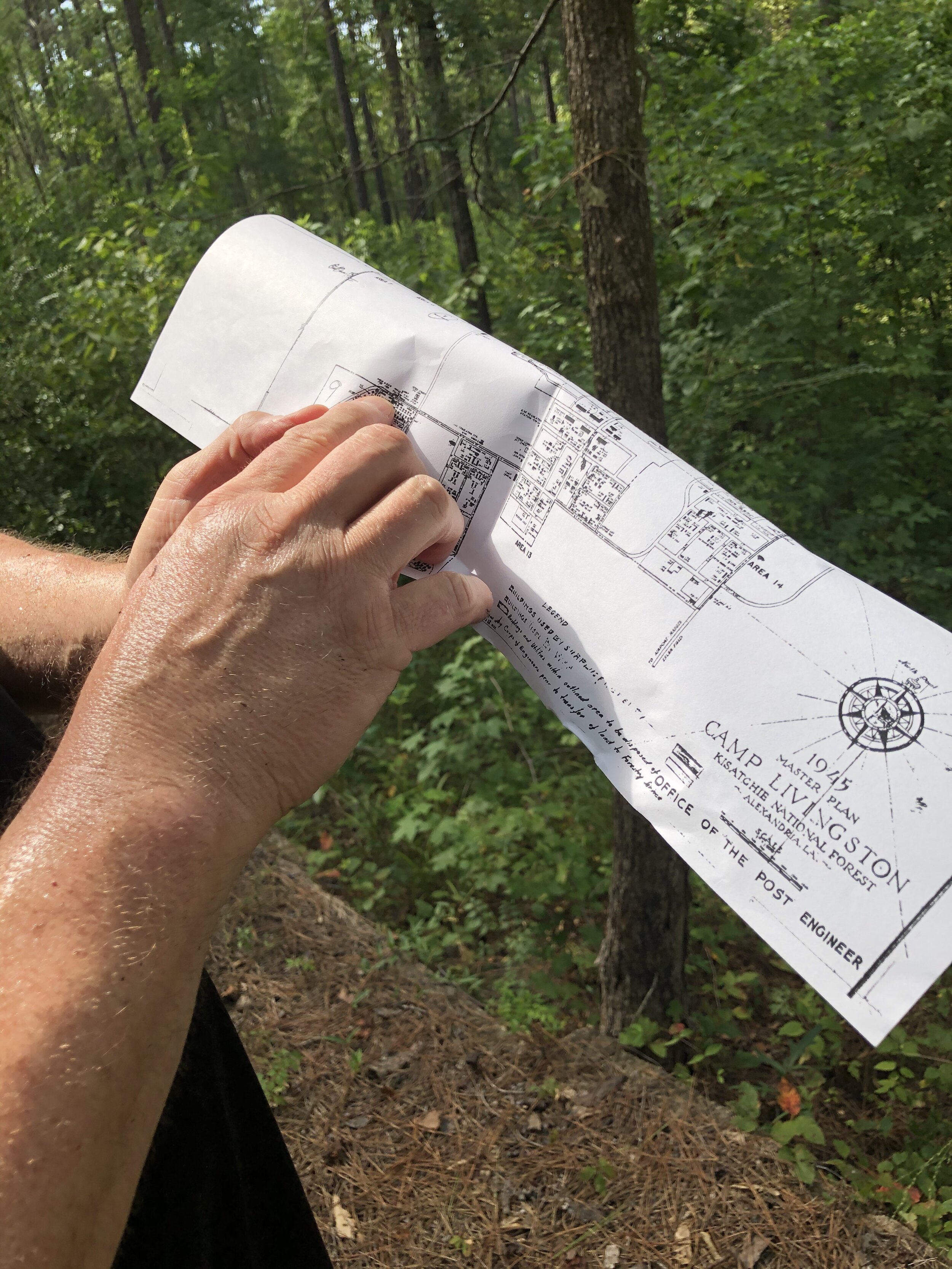

The first major breakthrough came on that trip to the National Archives. They’d expected it to resemble a university archive. Instead, it seemed more like Fort Knox: badges and trainings; cameras and guards watching their every move. Eventually, they located a full roster with more than a thousand names on it, and they found the camp “completion reports,” which held all available information about the camp — architectural plans, invoices, memos, photos, and so forth. The first three volumes only pertained to the military base — not that useful — and when they opened Volume 4’s box, it was gone. Missing. “I was just livid,” Johnson said, and, nodding her head toward Simms: “She had to take a lap around the building.”

That might have stopped the project, but they had anticipated setbacks. They requested the boxes on either side of the missing file, and sure enough, there it was: a blue file labeled “alien internment camp,” the number 4 scrawled in the corner in red ink, misfiled for who knows how long. And now they held it in their hands. Inside they found reports, blueprints, more memos, and a black-and-white photo of internees planting a garden beside a latrine. “That was the first time we saw photographic proof of these men in camp,” Johnson said. “It just made it so much more real.”

The librarians won another round of ALA grants to dig through the archives at the Japanese American National Museum at UCLA. While in Los Angeles, they met with Duncan Ryūken Williams, a Buddhist priest, professor, and author of American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War, a look at nearly 300 Buddhist priests who served time in various camps, and how faith helped internees survive. Furuya wrote about the priests at Livingston, too, recalling a Buddhist funeral attended by 58 Buddhist priests, 22 Shinto priests, and seven Christian ministers. The religious leaders prayed for the man who had died of illness, while “the voices of dozens of Buddhist priests reciting sutras blended in harmonic rhythm with the sound of the wind blowing through the pine forest, a strange atmosphere of both solemnity and splendor.”

With the help of oral histories, letters, government documents, and more, Johnson and Simms corroborated Furuya’s recollections. The commander of the camp allowed internees to largely govern themselves. They kept house, ran the mess hall, and maintained latrines. Two camps back, their families had sent each of them a suitcase full of clothes, which they preferred over hand-me-down fatigues. They were allowed to write one letter per week, but postage was expensive and letters were censored and sometimes lost. Most of the men were in their 50s, but they ranged from 20-80. In their lives before the war, the majority were professionals — teachers, bankers, businessmen, journalists — men invested in the life of the mind, practiced in diversion and sport. They read books, prayed, sang traditional songs, weaved pine needles into hats, carved sculptures out of tree roots, and showed them off. They taught each other singing, crafting, agriculture, theology, Spanish, and English, calling the project “Internee University.” It was a small society with various roles. Furuya was nominated chief of the athletic department and oversaw the construction of a crude golf course and a baseball diamond. He organized games and procured the equipment to play them. His favorite game was Go, which he played with rocks and scraps of cardboard. Only kendō was banned. The guards thought it risky to allow the men to practice a martial art. But no revolts were in the offing. The internees were simply whiling away the days, retaining from their old lives whatever they could.

Johnson and Simms are finishing up a book titled Beneath Heavy Pines: Louisiana, Camp Livingston, and Japanese Enemy Alien Internment, which is forthcoming with LSU Press. With the help of a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, they’ve also partnered with historian Greg Robinson, a professor at the Université du Québec À Montréal, to create a digital repository of Livingston-related material to archive on Densho.org, a website run by a nonprofit of the same name. (In Japanese, Denshō means “to pass on to the next generation.” For more than two decades, the group has preserved oral histories and other materials related to Japanese American incarceration during the war.) Robinson has published several books on the subject, including By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans. In his early research, he came upon a series of articles that FDR wrote in the 1920s that gave insight into his views on Japanese immigration. “He had supported the exclusion of Japanese immigrants and the laws that kept them from becoming citizens or owning property,” Robinson told me. “All because that was how he needed to defend white racial purity against intermarriage.” FDR held a rather common white view of what it meant to be an American, Robinson said. The Japanese, not European white and often not Christian, didn’t fit the mold.

In the summer of 2019, Johnson and Simms traveled to Honolulu where they met with descendants of the camps and pored over more documents at a university archive and at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii or JCCH. Going to Hawaii changed everything. “It brought it full circle,” Johnson said. “Closed the gap.” They visited temples where internees had worshipped and saw schools where they had taught. They were asked to give a talk at the JCCH. They had given presentations like this before, but never for a crowd of Japanese Americans.

“The people who came to our presentation were all affected by this,” Simms said. “Hawaii was the first time we had an audience come up to us afterward and thank us, validating that yeah, you’re not Japanese, but it doesn’t matter. The important thing is sharing the history.” Simms likes to say the story wants to be told. Doors have opened at every turn. “Once you pull on those threads, they are everywhere, and they are all incredible,” Simms said. “All the stories are just fascinating and heartbreaking, and at the same time uplifting.”

Troop B of the 106th Cavalry (Chicago National Guard) marching at Camp Livingston in 1941.

I pulled on a few of those threads. Jane Kurahara is an 89-year-old retired school librarian and volunteer at the JCCH who led the charge to rediscover another forgotten camp. In 1997, Kurahara was at the JCCH when a television producer called and asked the whereabouts of Honouliuli Internment Camp. Kurahara knew little about the camp, but she called around and people either knew almost nothing or had never even heard of the place. “We realized there was this hole in our history,” Kurahara said.

Finding the camp took five years. Preserving it and making it an educational destination took much longer. The camp had been nestled in a gulch in the interior of Oahu, earning it the nickname “Hell Valley.” It was run by the Army, the largest and longest-running internment camp in Hawaii. At the time of its rediscovery, the land was privately owned. Five years later, the Monsanto Corporation bought it and pledged to work with Kurahara and the preservation group that she led. As the group was raising funds to buy the land, Monsanto decided to donate the entire gulch to the federal government.

“We were just flabbergasted,” Kurahara said. “All along the way it seemed like every time we hit a wall, gradually, someplace along the wall would open up, and we’d keep going. It happened with Obama, too.” In 2015, Honouliuli Internment Camp was named a national monument, and President Barack Obama welcomed Kurahara to the Oval Office at the signing of a bill to protect Honouliuli and several other sites of cultural importance.

Kurahara and the JCCH have been working with Hawaii’s Department of Education for years. They created lesson plans with primary sources that have become standard curricula for all the schools and libraries in the entire state. She recalls a teacher telling her once: “I can teach them the information. I need you to help us help the kids develop empathy.”

So, Kurahara set out to do just that. For years, the JCCH has routinely invited high school students to volunteer to reenact the Issei hearings, reading verbatim from the transcripts. A question that consistently startles students is: “If your blood brother was in Japan and you met him in battle, would you kill him?” To say no signaled disloyalty to the United States. If they answered yes, then the board thought they were lying. Either way, they were sent to the camps. The hearings amounted to an exercise in cruelty.

Kurahara said to really understand how the internees endured you have to know something about Japanese values. “‘Gaman’ has to do with quiet endurance,” she said. “And ‘shikata ga nai,’ has to do with just accepting something that you cannot change.”

Satsuki Ina’s mother, Shizuko Ina, her brother Kiyoshi, and herself at Tule Lake Segregation Center in California, February 1945. Cameras were contraband at Tule Lake, Ina said, but when the young men who were drafted into the military out of the prison camp came to visit their families during R and R, people would ask them to take photos of the children. (Photographer unknown.)

Kurahara was 10 when Pearl Harbor was attacked. Her family lived nearby, and she remembers that Sunday morning well. It was incredibly noisy, but by that afternoon her world had calmed down. She ventured out with her father to speak with the neighbors, who showed them shrapnel that had fallen on their porch and crashed through their walls. “As we were talking, this car pulled up, and this great big policeman came out with a great big rifle and he came straight for us, ” she said. She hid behind her father as the policeman questioned him and ordered them back inside. “We were terrified,” she said.

I asked Kurahara why she thought the feds went after the leaders of the community, rather than ordinary people. “If you imprison the leaders, maybe the rest of the community will be easier to manage,” she speculated. The federal government was attempting to quell espionage, an alleged “fifth column.” A plan to intern Hawaii’s entire Japanese American population — all 158,000 of them, more than a third of the population — was scrapped at the last minute. In the end, about 2,000 were sent to camps, a decision more economic than of national security. The Japanese worked the sugar plantations. They dominated commercial fishing, and ran markets and stores. And so after Pearl Harbor, life continued in Hawaii under martial law.

Kurahara had a friend whose father was taken away, and the girl kept it secret from everyone at school. “She didn't tell me this until 60 years later,” Kurahara said. Shame and fear hung over the islands. Japanese Americans left behind often viewed the ones interned with suspicion.

But those who stayed were still profoundly changed. Kurahara stopped speaking Japanese. It was too dangerous, she said. “That cut me off from my grandma because she couldn't speak English.” It was only later that she understood the cost. I asked if justice was possible, and if so, what it would look like. Of all my questions, she said this was the hardest to answer. “The redress and the reparations helped the healing,” she said and drifted off.

Kurahara pondered a better response, then continued: “When John Lewis passed away” — the civil rights hero and Georgia congressman had died six days earlier, on July 17 — “this is a quote I picked up that author Michelle Alexander put out, and I thought, maybe this is it: ‘We must face our racial history and our racial present. We cannot solve a problem we do not understand.’”

“History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people.”

—

Martin Luther King Jr.

Satsuki Ina has spent a lifetime studying collective trauma among Japanese Americans, and as a licensed clinical therapist, she has helped individuals and families who have endured trauma for generations. “After Pearl Harbor, people knew that it was dangerous to be Japanese,” she told me. “There was so much hatred and racism. People burned their Japanese clothing and photographs and letters.” It was a matter of survival, forced assimilation. For the first time, parents gave their children English names and gave up teaching them Japanese. Many stopped going to Buddhist temples. They rarely, if ever, spoke of their internment. Ina’s parents lost hope America would protect them.

Ina, 76, was born at Camp Tulelake in Northern California. Later, she and her family reunited with her father at Crystal City Alien Enemy Detention Facility, a DOJ camp in south Texas, where they stayed for six months after the war ended, awaiting deportation in terror, an outcome that miraculously never transpired.

Ina’s experience informs her clinical work and led her to make two documentaries: “Children of the Camps” and “From a Silk Cocoon.” During the Obama administration, in 2015, she learned about a new Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility in Karnes City, Texas, built to hold women and children, most of them Central American. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, she decided to go undercover as a member of an interfaith group to investigate the facility and how it was run. It was a “chilling firsthand experience,” she told me, revealing “clear symptoms of severe depression and trauma” among the children detained there. “Children who were regressing in their behavior, who were angry, who couldn't sleep, who had night terrors, and becoming more angry with their mothers.”

Ina went back many times, going as far as testifying in hearings against its licensure as a childcare facility, an effort that was ultimately lost. As her work around the issue grew, she helped create an informal coalition of camp survivors and their descendants, formed to protest the locking up of asylum seekers, especially children, without due process of law. They called the network Tsuru for Solidarity. (“Tsuru” means crane, a symbol of “peace, compassion, hope, and healing.”)

In March 2019, Tsuru made its first public appearance at the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, the largest ICE detention center in the United States. The site is only a 45-minute drive east of Crystal City, where Ina and her family had been interned. The activists, some of them in their 80s and 90s, affixed thousands of brightly-colored origami cranes to the fence surrounding the place. Accompanied by Latinx activists and other allies, they gave speeches in front of banners that read “Stop Repeating History!” and “No More U.S. Concentration Camps!”

Next, they staged a protest at Fort Sill, where the Trump administration intended to send 1,400 immigrant and refugee children to be detained. Elderly camp survivors stood toe-to-toe with military police, vowing to go to jail if necessary. (The threat was real: bases have the legal right to ban protests on their grounds.) Less than a week after the demonstration, the government reversed course and canceled the plan, blaming a lack of “immediate need.”

Tsuru has teamed up with Black Lives Matter, United We Dream, Detention Watch Network, and other grassroots activists groups, and carried their messages across the county. Following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, Tsuru members joined the global uprisings this summer against police brutality and mass incarceration and protested in front of the Cook County Jail in Chicago. The movement continues to grow.

Tsuru for Solidarity is an informal coalition of camp survivors and their descendants who have staged protests against the locking up of asylum seekers, especially children, without due process of law. “Tsuru” means crane, a symbol of “peace, compassion, hope and healing.” Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, 2019. Photo courtesy of Nancy Ukai.

Last August, I drove from my home in New Orleans to the Kisatchie National Forest to visit the Louisiana Maneuvers and Military History Museum at Camp Beauregard, a National Guard installation in Pineville, Louisiana, not far from where Camp Livingston once stood.

That part of Louisiana, the woodsy center, is more Protestant than Catholic, more white than Black, and Asian Americans make up less than 2% of the population.

I’m greeted by Richard Moran, a 53-year-old retired Army officer and curator of the museum. Having served two tours in Iraq, Moran has devoted much of the past two decades to running this museum and learning military history. He walked me through the exhibits, from the days when William T. Sherman ran the Louisiana Seminary of Learning and Military Academy (which relocated later to Baton Rouge and became LSU) to the history of the Louisiana Maneuvers, the name given to field trainings in the area before and after World War II, the largest of which involved close to half a million American soldiers in September 1941.

Richard Moran, a 53-year-old retired Army officer and curator of the Louisiana Maneuvers and Military History Museum at Camp Beauregard.

Moran explained the new display he was building with input from Johnson and Simms, which, for the first time at the museum, would recognize the nearby internment of both POWs and civilians. “I want to show the duality,” he said. “We had legitimate prisoners of war — Italians, Germans, and Japanese — and then we had Americans.” The display will also feature Japanese American visitors to the camp, including members of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an army unit of more than 4,000 volunteer “Nisei” soldiers stationed at Camp Shelby in Mississippi. Some of these soldiers had relatives in Camp Livingston. Putting together a display takes time, Moran said. He’d need to acquire mannequins, wardrobes, and artifacts, and the pandemic has slowed things down. Moran hopes the display will be ready for the public sometime later this year.

The previous week marked the 75th anniversary of the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As we stood beside the museum’s rarest artifact, a tattered Japanese battle flag that once flew above a warship in Hiroshima’s harbor, Moran said, “I always ask everyone. Should we have dropped the atomic bomb?”

“There's a lot of evidence to suggest that it wasn't necessary,” I said. “But there's a big debate about that, especially the second bomb.” I was thinking of an op-ed that claimed President Harry S. Truman knew Japan’s surrender was imminent before the bombings but ordered them anyway — not one bomb, but two — a grim signal of global military superiority and, in my view, an unconscionable twist of the knife.

In response, Moran said that had ground troops invaded Japan in lieu of bombing, both sides would have sustained more casualties. He also mentioned a Japanese man from Hiroshima who once visited the museum and “didn't hesitate” to side with the standard American account: “[The bombings] ended the war, and now we're vast allies. It was a horrible thing to do, but a necessary evil.”

I rode along in Moran’s SUV as we talked about the land and our lives and all of this history. It was as hot and muggy as you’d expect. I imagined Furuya, the same age as Moran, lugging his suitcase from the train to his barrack beneath a punishing sun, wondering how in the world he’d ended up in this far-flung forest through no fault of his own. I was also worried about my stepfather, who lay in an ICU bed in Oklahoma, having endured open-heart surgery two days before. Moran’s own father was in the hospital battling COVID-19. (Days later, the terrible disease took his life.) The fragility of life was on my mind that afternoon, how easily our loved ones can be taken away.

Moran turned onto a single lane, dense woods cleaving to both sides, trees so tall you had to look up to see the sky. Many thousands of acres had once been cleared to build the camp, and after its closure, the structures were dismantled and sold off by the board foot. We’ll likely never know how many nearby homes and stores were built with the lumber. After the war, Moran said, the Forest Service replanted these trees. The forest filled in and healed.

Moran made a curve, pulled onto the shoulder, and parked. This was the place, the north edge of a rectangle he showed me on a map, labeled “Area 20.” Without warning, he dashed into the woods, and I followed as he beat a path through lush undergrowth, knocking down spider webs, gingerly stepping through tangles of thorny briars.

“In the winter you can actually see it from the road,” he said, but he still hadn’t told me what exactly we were looking for.

Minutes later, he pointed out a chunk of concrete protruding from the ground. We walked a little farther and more concrete appeared among the trees: a whole slab, the base of a long-gone structure, the face of it painted white or gray, now weathered and peeling away. This was most likely an administrative building; the barracks had been made of wood, and no sign of them remained.

An ant bore its stinger into Moran’s knuckle, and he spoke up about it just as I noticed we were standing in what looked like poison ivy. There were more slabs like this one, Moran said, but he wanted to show me other parts of the camp, where the troops had stayed and entertained themselves. We located the remnants of an enormous swimming pool and the floor of the old basketball court, where Moran said soldiers would roller skate. We found a large loading dock, its brittle concrete falling away, exposing rusty rebar, weeds, and small trees sprouting from its cracks. Supplies would have come in on trucks and trains, Moran said. It was also likely where internees came by rail before they walked with armed guards to their barracks on that desolate road.

Moran pointing out “Area 20,” where the internment camp was located at Livingston’s southern edge (left). A crumbling loading dock where trucks would come in to deliver supplies. On the other side of the dock was a train platform where prisoners would have arrived before walking to the barracks (right).

I didn’t belong in these woods. Nobody does, not even Moran, and he grew up only a few miles away. To the extent that the area is maintained, the Forest Service is charged with the job. The only people who venture there now are the occasional camper, hunter, or carload of bored teenagers, looking for seclusion to get into mischief. Among illegally dumped trash, I saw empty beer bottles and bullet-scarred targets nailed to trees.

Back at the museum, my car wouldn’t start, but Moran jumped it and escorted me to the auto shop. It was early Friday evening, and I was grateful for the help. After a new battery, I was good to go. On the way home, I passed one sugar cane field after another and pondered what I had just seen.

I grew up in rural Oklahoma, attending predominantly white, small-town public schools for 13 years, and never heard a word about most of its ugly past: not the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, nor the Osage Reign of Terror, nor the fact that 700 Japanese civilians (90 of them priests) had been forcibly interned at Fort Sill.

In 2015, Ina wrote, “It has been a life-long mission for me to educate others about this dark chapter of American history with hopes that it would never happen again.” Justice, for her, can only be achieved if our country makes Japanese American history a standard part of education, beginning in elementary school. In this respect, Hawaii is leading the way. I mentioned this to Ina and she said, “This sounds wonderful. And here's what I would love, programs like that in Arkansas.” I asked why she thought some people hesitated to confront this history head-on. “Rocking the boat,” she said without hesitation. “You don't have to be a traitor to say America has failed in its humanity to its people.”

Jason Christian’s essays and journalism have appeared in the Baton Rouge Advocate, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Country Roads Magazine, Gulf Coast, The New Republic, Scalawag, and elsewhere. He lives in New Orleans with his wife. You can find more of his work at jasonchristianwrites.com.