Story by Shane Mitchell | Photographs by Amanda Greene

In a dream I meet

my dead friend. He has,

I know, gone long and far,

and yet he is the same

for the dead are changeless.

They grow no older.

It is I who have changed,

grown strange to what I was.

Yet I, the changed one,

ask: “How you been?”

He grins and looks at me.

“I been eating peaches

off some mighty fine trees.”

— Wendell Berry, “A Meeting”

“Where the hell is this grave?”

Late on an afternoon when the heat index hovered near second-degree murder, I stood on a slope overlooking hundreds of squat white headstones descending row by regimented row to the railroad tracks at the verge of Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Georgia. Each marked by a dollar store battle flag stuck in the ground. A plaque erected by the Ladies Memorial Association identified the plot as Confederate Soldiers’ Square.

I was clearly in the wrong place. No guitar hero here.

“Go ask someone,” shouted my husband, Bronson, answering his phone when I called home for guidance.

A man walking his pit bulls finally pointed the way, and I scrambled across a series of overgrown terraces, apologizing to the forgotten dead in an effort to find the man nicknamed Skydog, who adopted an empty glass Coricidin bottle as a slide for his Fender Stratocaster.

Established in 1840 as a final resting place and parkland for Macon’s elite, Rose Hill contains a multitude of neoclassical mausoleums and obelisks, punctuated by specimen trees choked with climbing ivy, the ideal hideout for broke young musicians who wanted to get high on mushrooms and scribble song lyrics.

Helium balloons floated from the fence protecting their graves. Jasmine enveloped one corner where the first of the original band members lay at rest. A car pulled up on a pathway and several grizzled men climbed out. All lit up smokes and shambled to the brick terrace leading to the plot. They looked like bikers long past a last ride. One spotted me.

“Do you know where Elizabeth Reed is buried?” he asked.

I shrugged.

Another bent on creaky knees and scrabbled in the dirt, hunting for a rock to carry away as a memento. (Fans used to steal the decorative mushroom statuettes studding the graves until the family erected the fence.) After they drove away, I paid respect, texting pictures to my husband, the true believer, who should have been there with me.

The Allman Brothers Band formed during a volatile era of Vietnam War protests and the Civil Rights Movement, and the release of a live double album, “At Fillmore East,” which included the song “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” propelled them to fame in 1971. Before lead guitarist Duane Allman died at age 24 in a motorcycle crash, and was interred here later that same year, Good Times Magazine journalist Ellen Mandel interviewed him.

“How are you helping the revolution?” she asked.

Skydog’s reply would become Southern rock legend.

“Every time I’m in Georgia I eat a peach for peace.”

No tree of any other kind stood amongst them, but there were fragrant flowers, delicate and lovely to the eye, and the air was filled with drifting peachbloom.

— Tao Yuanming, “Peach Blossom Spring,” Jin Dynasty

Peaches arrived in Georgia by way of a circuitous route from China. (The earliest fossilized peach pits, discovered in the southern province of Yunnan, date back 2.6 million years.) The stone fruit known as táo was conveyed to the West by Silk Road trade caravans, gaining its Latin name, Prunus persica, from a stopover in Persia — then arrived elsewhere as persik, pesca, pêssego, pêche — and finally, across the Atlantic sometime after 1539, when Hernando de Soto, who apparently carried pits among the seed stores onboard his vessels, landed in La Florida. Peaches proceeded along de Soto’s trail from Tampa Bay to the Mississippi River. At least, this is one of the accepted narratives, since expedition chroniclers failed to mention peaches specifically. Another has peaches introduced by missionaries first to St. Augustine, and then St. Simons and Cumberland islands, later in the 16th century.

Once on the ground, peaches propagated so effectively that by the time naturalist John Lawson published A New Voyage to Carolina in 1709, he labeled them a pest:

We have a great many sorts of this Fruit, which all thrive to Admiration, Peach-Trees coming to Perfection (with us) as easily as the Weeds. A Peach falling to the Ground, brings a Peach-Tree that shall bear in three years, or sometimes sooner. Eating Peaches in our Orchards makes them come up so thick from the Kernel, that we are forced to take a great deal of Care to weed them out; otherwise they make our Land a Wilderness of Peach-Trees.

Lucky the pest tasted good. Peach butter, peach leather, peach cobbler, peach pie, peach sonker, peach marmalade, brandied peaches, pickled peaches, peach sherbet, peach cordial, peach bread, and an archaic curiosity, peach quiddany, all appear in the earliest Southern journals, household diaries, and cookbooks. A recipe for ratafia dating from 1830 calls for 1,000 peach kernels to be soaked in madeira wine. Lettice Bryan, author of The Kentucky Housewife (1839), provided an elaborate method for a jellied confection she titled “A Dish of Peaches,” the successor of quiddany (fruit jellies) and precursor to those Jell-O molds laid out on picnic tables at family reunions.

And peaches were a rare sweet fruit available in abundance, even to enslaved people.

That’s before peaches became an agricultural crop more valuable than cotton. In 1844, a London Horticultural Society botanist stumbled on the Chinese Cling growing in a walled orchard south of the city of Shanghai. Peaches are generally classified as freestone or clingstone, and fall into two further categories, depending on whether they have white or yellow flesh. From these traits come a world of varieties, but when the Chinese Cling, also known as Shanghai’s Honey Nectar, was subsequently imported as a potted plant in 1850 by nurseryman Charles Downing, it quickly caught on in American pomology circles for its size and flavor, equally balanced between tart and sweet, with a distinct almond note.

Then the Civil War changed everything and nothing. Cotton faded a bit. Peaches flourished a bit more. Somebody still had to pick the crops.

From the Chinese Cling comes the daughter peach we most often visualize neatly arranged in baskets at roadside stands or on the jacket of a Capricorn Records album dedicated to a deceased guitar hero. In 1875, Georgia peach grower Samuel H. Rumph crossed an open-pollinated Chinese Cling with Early Crawford, and the resulting juicy yellow freestone was characterized by a crimson blush on its cheek. He named it for his wife, Clara Elberta Moore. One of the earliest paintings in the splendid U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection is a Chinese Cling by Deborah Passmore Griscom from 1893. Her 1902 cross-section study of an Elberta affected by Leaf Curl sings of fruit gone bad. Yet Elberta became the commercial standard, so much so that Southern growers still identify the ripening season of other varieties either as days before, or days after, this prunus goes sploosh on the ground.

Seasonal peach stands open at the height of summer in the South.

Peaches come from a can,

They were put there by a man

In a factory downtown

If I had my little way,

I'd eat peaches every day

— The Presidents of the United States of America,“Peaches”

Lawton Pearson yanked open the door to his silver pickup and a peach rolled out. More were scattered on the dashboard, piled in the center console cup holder, and tossed on the back seat, hues from sunny yellow to muddy magenta, in stages of decay and ferment. His office manager, Vicki Hollingsworth, calls these “seat peaches.” The fifth-generation farmer holds a law degree from the University of Georgia but returned home 15 years ago to manage the family business.

“One day, when I just came back, I asked my dad, ‘What do you do for a living? What do you do? What do you actually do?’”

Pearson climbed behind the wheel.

“He told me, ‘I ride and look at peaches.’”

Fifth-generation peach farmer Lawton Pearson inspects fruit for ripeness in his family’s orchards.

Lawton Pearson adjusted his blue-and-white trucker hat over sweat-damp hair and rolled down the windows so the baked-cobbler smell in the hot cab swirled as we peeled out of the parking lot at the Pearson Farm packing shed.

In 1885, Moses Winlock “Lockie” Pearson, and his wife, Emma, moved to Crawford County, Georgia, during the postwar era that could be loosely termed the Peach Rush. They switched from milling timber to growing fruit, but he died at 48, leaving his widow with a dozen children. By 1917, their oldest, John W. “Papa John” Pearson, expanded the property with the purchase of a larger farm that included a boarding hotel for seasonal workers, a company store, a packing shed, and post office. At one point, he had 5,000 acres under cultivation. Pearson also patented a peach. According to his great-grandson, that didn’t go as well.

“Papa John found an Early Hiley sport in 1946,” Pearson said, turning down a dirt lane. “And an Early is always more in demand; you’d get better prices for them. He wouldn't share, so everybody was mad at him for patenting it. But then the market up North figured out that it was a miserable eating peach. The story goes he got a telegram that said, ‘Have received your shipment of Pearson Hiley peaches. When will you send sugar?’”

“What happened?” I asked.

“If a peach ain't sweet, there's no point in it.”

Fruit headed for the Pearson packing shed in Crawford County, Georgia.

Pearson passed a row of crew houses opposite the old boarding hotel. Men done with picking for the day waved from the porches. Like other orchards in the South, H-2A visa holders from Latin America have replaced mostly Black sharecroppers, and at the height of the season, the farm employs seven crews, each consisting of 16 pickers, two tractor drivers, and a crew boss; fathers and sons, who have crossed the border for multiple generations. Harvesters walk from tree to tree, scanning fruit for color and size, gathering the best in a picking bucket strapped to their chests. Pearson currently has 45 varieties, and 50 others in experimental trials on 1,700 acres; the daily yield at the height of the season is almost 10,000 half-bushel boxes.

“There’s yet to be a mechanized way to picking peaches,” he said. “And it’s going to be real difficult to teach a robot which one is ripe.”

“When do you know which varieties are ready?” I asked.

“It’s in my head. Have to be out there every day.”

Pearson Farm harvester Santos Grajeda selects peaches by hand.

Pearson steered between rows of trees bowed with fruit, close enough so he could reach out and grab peaches as low limbs whipped the side of the truck. He yanked several, took bites, and discarded them. Handed me a couple as well. One had a distinctly boozy aftertaste.

“I’m always trying to root out the good tasting from the bad. I don't want to ship something that somebody gotta spit out.”

Pearson cut another open with his pocket knife, grimaced, and pointed to a split pit caused by frost.

“Cold weather in March is what just makes or breaks us every year, so we're real particular about where we put orchards. Sometimes all I need is one degree. Just one degree. It’s the difference between profitability and loss. If you think too hard about it, you'll go crazy.”

He talked about altitude, airflow, and the equipment used to keep an orchard warm during a killing snap. Back in the day, hay bales were set ablaze. Now, it’s wind turbines. Husbandry still relies to a certain extent on acute observations a peach farmer makes among his trees every day.

“The birds will tell you where the sugar is,” Pearson said. “Jays are mad for them. You'll see crows, too. A lot others you don't realize are here, like brown thrashers and mockingbirds. Although they don’t like some varieties, they have preferences.”

A pecan grove cast shade on one side of the orchard. The Pearsons started interplanting three generations ago, because a fall nut crop keeps the lights on and bills paid after the 12-week peach season ends.

“That's some really good peach dirt right there, but it will never get back in peaches.”

“What makes good peach dirt?” I asked.

The sweet spot for growing peaches lies in a 20-mile swath of rolling hills known as the Fall Line, a geological transition zone between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. Stretching from middle Georgia into upcountry South Carolina, this sandy, loamy soil essentially parallels what would have been beachfront in the Mesozoic Era. It runs straight through Peach County and is home to Georgia’s “big four” peach growers: Pearson, Lane Southern Orchards, Dickey Farms, and Fitzgerald Fruit Farms.

Lawton Pearson cuts open one of his “seat peaches.”

Pearson parked next to his heirloom block, a grouping of tightly clustered trees less pruned than his commercial blocks. Oddball trees, nearly obsolete, just for the heck of it.

“Most of these peaches we grew at one time or another, but they didn’t have enough red color. Because now the consumer thinks red means ripe, and that’s sad.”

He pointed to each tree.

“This is Southland, one of the best eating peaches there is, and nobody grabs it. That’s a Topaz. It often doesn’t set well, goes all cattywumpus, still it’s delicious. There’s the Virginia series: Jefferson, Monroe, Washington, all the presidents. We also have a block of Elberta that can be traced back to the original tree.”

“Hands down finest peach to eat?”

“Probably an August Prince or Scarlet Prince.”

“Pie or cobbler?”

“Cobbler.”

Both our seats were piled with fruit; a few more landed on the rubber floor mats. I reached out the passenger window and pried loose a desiccated peach wedged in the crotch of the rearview mirror.

“And this one?”

He beamed.

“Sun dried.”

The heritage-variety block.

With my whole body I taste these peaches.

— Wallace Stevens, “A Dish of Peaches in Russia”

“I always think about young trees as small babies,” said Dario Chavez. “When you first plant them in the field, you want to actually take care of them like a newborn.”

Born to a family of dairy cattle farmers in the Ecuadorian Andes, Chavez first studied blueberries, then switched to stone fruit for his doctorate. Since 2014, he has served as the peach specialist at the University of Georgia’s Department of Horticulture, where he was offered his pick of land parcels to build a research station specifically devoted to nursing peaches. He chose Dempsey Farm, an overgrown 12-acre plot near the Griffin campus, an hour north of Peach County. Every major peach grower in Georgia has his cell number on speed dial; his phone kept jangling in the pocket of his cargo shorts as we hiked through the orchard on a sweltering morning.

Peach specialist Dario Chavez surrounded by his “babies” at University of Georgia’s Dempsey Farm.

“How many varieties are you growing?” I asked.

“About 185. All of these trees that you see here basically were grafted and propagated by us.”

He bent to lift a limb loaded with fruit that was weighing down his new trials of dwarfing rootstock. Originally, all peaches had white flesh. Yellow is a genetic mutation.

“The flavor of a white is different, milder; it also has more florals,” he said.

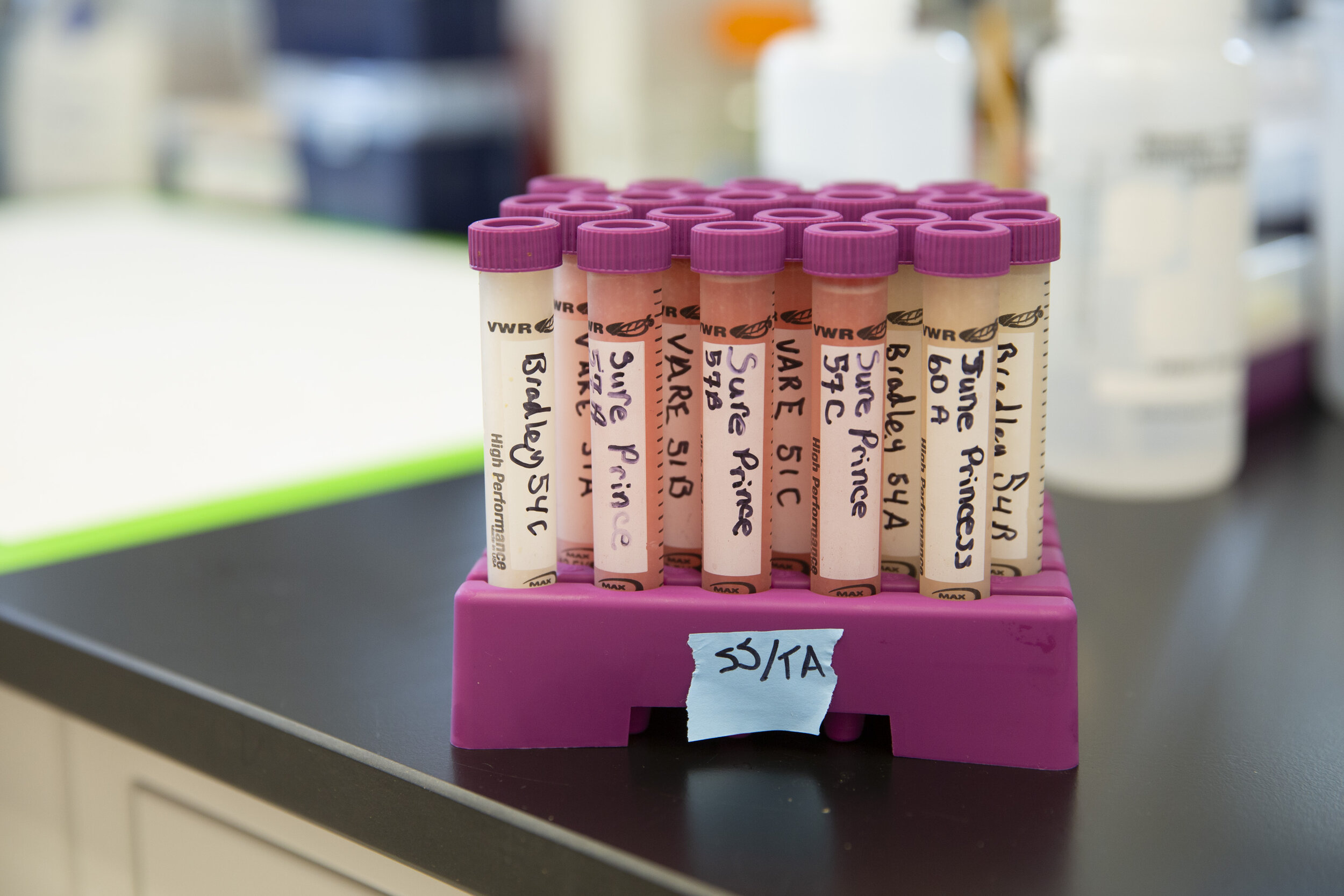

The Chavez Lab conducts experiments on pollen, germplasm, rootstocks, and the brix (sugar content) of peach juice.

The flesh of peaches can be classified as either melting, nonmelting, or stony hard. This means some varieties have a firmer texture than others, more suitable for canning or cooking, while the mouthwatering “melters” are most anticipated when signs advertising ripened fruit appear along the road during their all too fleeting midsummer season.

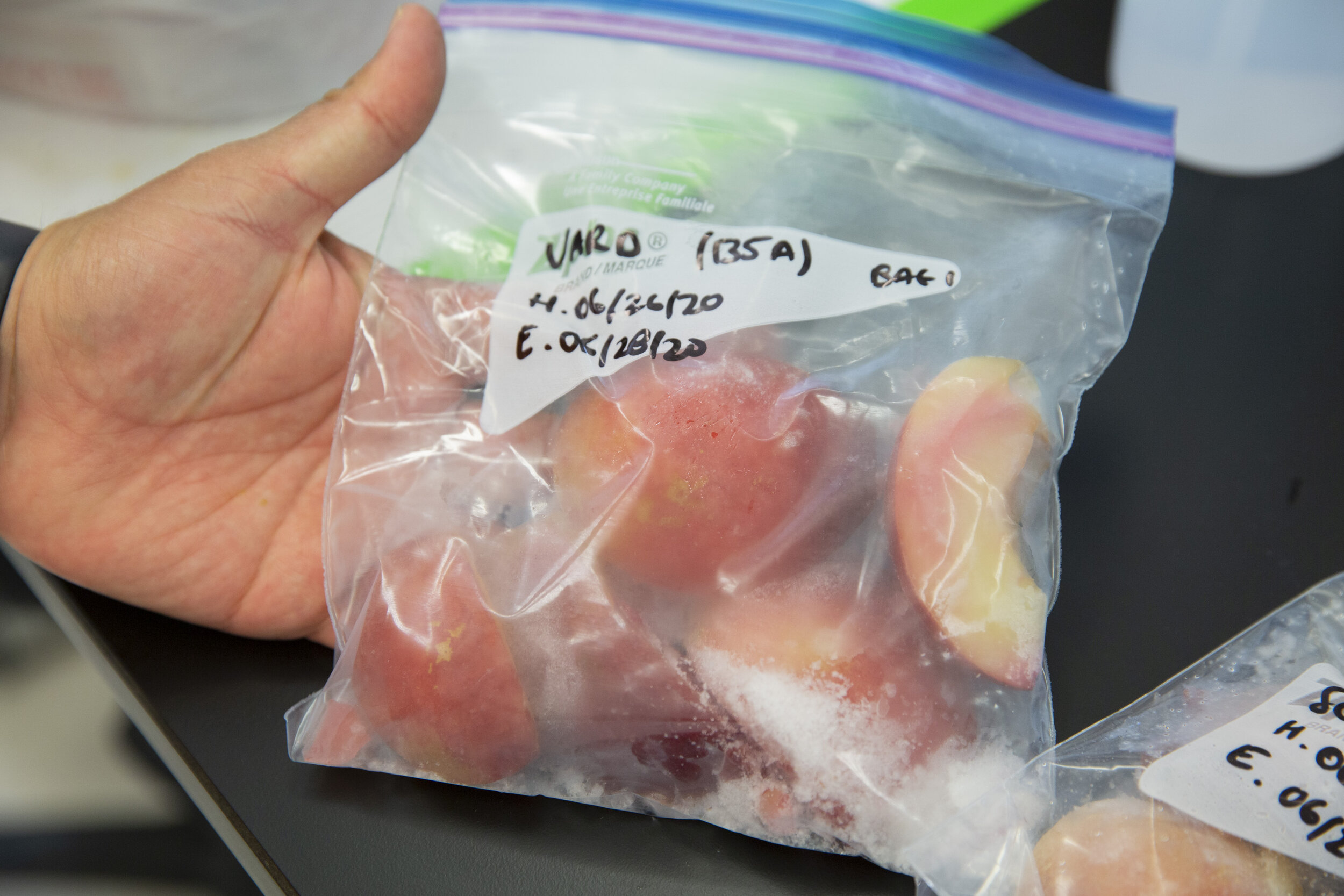

Peach research at the Chavez Lab.

I began to melt a little as well. We found shade in a mixed-variety block, where the red soil was littered with brown pits from last season’s fruit.

“If you want to grab some, you're welcome,” Chavez said.

Several trees had white tape floating from their branches.

“We mark the plants that are ready for people to harvest. Anyone from UGA can just come pick. When we’re doing research trials on yield, we actually gather all the fruit and truck it to campus. We don't send an email or anything, people start telling everybody, and in an hour or two, the trucks are empty.”

I reached up into a tree.

“Which is this variety?”

“Flavorich.”

One of the pretty, freckled peaches came away wet in my hand. Then I heard plop-plop-plopping among the leaves.

“Oh my gosh, it’s raining juice!”

Chavez laughed.

“That’s the difference from getting one in the store, right?”

“So, pie or cobbler?” I asked.

“Ice cream. OK, cobbler, because I can put peach ice cream on top. The growers sell it at their fruit stands. Cannot make a mistake buying a little of it.”

Chavez walked ahead, happy to be among his babies. After standing too long under the obstinate sun, I sucked that Flavorich dry.

Si te gusta el durazno, bancate la pelusa.

If you like the peach, put up with the fuzz.

— Argentinian saying

“What’s the difference between a peach and nectarine?” asked Jeff Hopkins, the farm manager at Clemson University’s 240-acre Musser Fruit Research Center.

“Fuzz?” I said.

“What else?”

Caught off guard, I squinted at specimens arranged in cartons on a lab table.

“Uh, nothing?”

“Right. That was a trick question.”

We were joined by pomologist Greg Reighard, who thumbed through his first edition of U.P. Hedrick’s The Peaches of New York (1916) to show me illustration plates of 19th-century varieties favored by fanciers on the Eastern seaboard, including some cultivated in the Carolina Piedmont centuries earlier. Family Favorite, Late Crawford, Old Mixon Free, Summer Snow. Lemon Cling. Blood Cling. Before 1897, Blood Cling was also known as Indian Blood, Indian Redmeat, Indian Cling. An astringent peach with dark red flesh mostly good for fruit leather or pickling.

“Peaches were really a common fruit crop for Indigenous Americans from the 1600s onward,” said Reighard, whose specialty is disease-resistant rootstock.

“Historically, this was a peach-growing area?” I asked.

“Well, it was for the Cherokee. But they didn't have the diseases we have now, and the climate had to be different, because they planted their orchards along the Seneca River. That's a low spot. We plant on a high spot.”

Lab samples at Musser Fruit Research Center in Seneca, South Carolina. An illustration plate in U.P. Hedrick’s The Peaches of New York.

The Musser orchards occupy Oconee Point on Lake Hartwell in Seneca, South Carolina, and lie above the Fall Line in the Piedmont region. The Upper Road of the Occaneechi Path passed through here; this Indigenous trade route network was a conduit for furs, shells, seeds, and other valuable commodities. Those peach pits, too, soon after de Soto marched to his vainglorious death on the banks of the Mississippi. The Muscogee Creek and Cherokee became the continent’s first true peach orchardists. (The Cherokee word for peach is ᏆᏅ or qua-na.) Accounts by European explorers and botanists describe villages along the great trading paths surrounded by fruit trees, which thrived until white settlers coveted those autonomous territories and treaties got trashed.

When President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, Cherokee leaders protested. On July 24, 1830, the Cherokee Phoenix, the tribal newspaper, published these words of Going Snake, a respected Speaker of Council, “... orders may arrive to prevent us from working in our fields, planting Orchards, or putting down wood to make our fires.” Resistance proved futile. Land confiscated, livestock looted, farms and towns destroyed. Compensation paltry, if at all. Between 1830 and 1850, almost 100,000 Indigenous people in the Southeast were forced on a genocidal march across the Mississippi. The Cherokee named this deadly journey ᏅᏃᎯ ᏛᎾᏠᎯᎸ, Nv-no-hi dv-na-tlo-hi-lv, or the Trail Where They Cried.

Their peaches went feral.

“No one was maintaining those orchards,” said David Anderson, tribal horticulturalist for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, when I asked for clarification. “But this is where the nurserymen of the South came to get their genetic stock to work with, here in northern Georgia, western North Carolina.

“You find these peach trees scattered on Appalachian homesteads, freaks planted on tribal land for preserving and fresh eating, isolated in western North Carolina,” he said.

Greg Reighard concurred.

“When I started here in the ’80s, my predecessor collected a lot of what they call Tennessee Natural and Indian Cling peaches,” he said, turning pages in his book to find the Blood Cling plate. “These were wild peaches growing in the forest or on fence rows. We also selected samples from some trees in the mountains two years ago. Someone told us about a pocket of them, but you don't find peaches as an invasive species anymore. Most times when I see wild peaches now is along roadways where people throw out a pit.”

We talked about how different peaches got their names. Unlike heirloom apples, modern peach varieties lack the same hype, although that wasn’t always the case. In the late 19th century, the American Pomological Society had final approval of new name releases, and after the Civil War, the focus shifted from presidents and generals to hue and character, with an emphasis on sunshine and pretty ladies, hence the Belle of Georgia, introduced by Lewis A. Rumph, uncle to Samuel of Elberta fame.

“Hedrick wanted to stop these ridiculous multiple names that were coming up, like Stump the World,” said Reighard. “He hated that name.”

We left him in the lab, and on the way out to the orchards, Hopkins stopped at the walk-in cooler in the farm’s post-harvest room. The potpourri scent inside reminded me of the perfume counters at the old Davison’s Department Store on Peachtree in Atlanta.

“How are you testing for aroma?” I asked.

“With peaches, it's interesting,” he said, examining bins of plums, apricots, and nectarines collected that morning. “Once you cool a peach, the aroma gets locked up. Fresh off the tree it’s always going to smell like peach; if you get one out of a cooler, it takes a day or two on the counter to recondition and have that nice peachy aroma again.”

Georgia put peaches on license plates and the tails side of quarters. South Carolina branded itself the “tastier peach state.” The rivalry remains as deep as that between certain bulldogs and tigers. No contest, Carolina grows more. Both states are dwarfed by California, and China still produces the most by volume.

We walked across a sloping field into the advanced-selection block on the high point of a hill facing a sluice pond. Birds chattered in the still summertime air. Hopkins explained they evaluate hundreds of varieties for flavor and aroma.

“But these are ones that, you know, for one reason or another, may become the future of the Southeast.”

He pulled several fruit off a random tree, rubbed one on his Clemson Tigers shirt.

“One of my personal pleasures is to browse the variety trials when everything’s tree ripe. I mean, just as ripe as they can get; perfect peaches. And they’ll have flavors of coconut, pineapple, black pepper, lemons, limes.”

Hopkins shook his head, wonderingly, and handed me one.

“How can there be so many flavors in a peach?” I asked.

We both took bites.

“Um, this is gorgeous,” I said.

“Best lunch of the week. You're one of the select few that’ll ever try this one.”

“What’s it called?”

He made note of a tag on the trunk.

“It's SC-10.”

“Needs a better name than that,” I said.

Later that afternoon, the woman responsible for the SC-10 hybrid hopped on a golf cart handed down from Clemson’s athletic program and drove out to the mother block. A Lowe’s tool apron tied at her waist, Ksenija Gasic is Clemson’s peach breeder and geneticist. She consulted her phone and counted down the row until we reached a couple of sorry-looking, buggy specimens. While commercial growers tend to keep heritage peaches as novelties, she hangs onto them like an ancestral portrait in a treasured family album.

“These are the oldest tree varieties at Clemson?” I asked.

“Old Mixon Free and Late Crawford. I got the germplasm from the USDA prunus repository in California.”

She walked down the row, checking for disease.

“I need to have a block where I can put the material, or cultivars, that I like as the ‘parents.’ I can get pollen from anywhere around the world, but I need a mother tree, you know, with the good qualities that I like.”

Clemson University’s peach geneticist Ksenija Gasic amid the oldest varieties in her “mother” block.

Born in Serbia, Gasic emigrated to the States in 2001, and was hired by the university to kick-start a breeding program for peaches compatible with current Carolina growing conditions.

“Serbia has a different environment,” she said. “The issues for peaches are different. That was a learning curve, because everything here is a month earlier, even the ripening times, you know?”

“How many trees have you planted at Clemson?” I asked.

“Around 30,000 over the years,” she said. “Every year we would put in 4,000 trees, then in 2010, we put in 10,000. When they all started ripening, I said never again, because I would basically be eating peaches the whole week, and by the time I got to the end of a block, I had to start over again on Monday.”

“I haven’t had anything else today, and my stomach feels it,” I said.

“The first week this year, I ate so much that my teeth acidified,” she said. “Early peaches are not sweet, so I had to neutralize the pH in my mouth. A lingering taste on the palate can throw off the flavor of the next sample. But I couldn’t stop, I just love them. That’s insanity.”

Then I mentioned the fantastic white peach. She brightened, climbed into the golf cart, and went looking for it. We picked and picked, trying not to be greedy, two short women entangled among branches, arms stretched for really ripe ones inches beyond our reach. Pinky orange, the color of smudged rouge. Bins on the back seat of the cart filled with fruit.

“You cannot beat the white ones,” Gasic said, “because the carotenoids that get spent creating yellow flesh, they all stay in the white ones and that's what gives them the aroma.”

She took a breath, and coughed sharply.

“Too much fuzz in the air.”

She's so cool and I'm so ugly

I'd be a fool to think that she could love me

This kinda girl's always out of reach

She's a peach

— Prince,“Peach”

“Oh! This cobbler is so good,” said Sydney Dorsey, politely covering her mouth while juggling a plastic bowl, spoon, microphone, and the rhinestone tiara wobbling on her head.

Miss Georgia Peach had the first taste of the “World’s Largest Peach Cobbler” — 75 gallons of peaches, 70 pounds of butter, 150 pounds of sugar, 150 pounds of flour, 32 gallons of milk — baked in a brick oven lined with school bus floor panels next to the county courthouse during Fort Valley’s annual peach festival. The line for free cobbler wrapped around concession stands and down the block.

It’s a long day for Dorsey, from flipping breakfast pancakes to signing autographs at one of the orchards outside town. The 19-year-old pageant winner and her sister queens gathered early in the lobby of the Austin Theater, an opera house that had seen better days, where the five girls changed into semiformal dresses and reapplied makeup already melting. Dorsey wore a peach-orange pleated chiffon mini-dress and glitter ankle boots. The youngest, Tiny Miss Georgia Peach, was 6 years old. She had a loose front tooth, and proudly wiggled it for the others.

“Where did you leave your sash, Ava?” Dorsey asked, helping to bind her hair into angel wings.

Their mothers, one dad, and two pageant chaperones bundled the court off to parade vehicles parked on a side street. A field tractor with bins of fresh fruit. One Shriner, no go-kart. The deputy mayor in a flatbed. A lemonade van. A ladder truck. Convertibles for the girls. When the fireman burped his siren to signal the start, the peach queens rolled.

A day in the life of a Peach Queen. Georgia Peach Festival, Fort Valley, Peach County.

The Miss Georgia Peach pageant was revived in 1996 — after a hiatus for lack of participation — and a talent segment was mandatory back then, even for the youngest titles. Now, the emphasis is on poise and charm. Scholarships, not swimsuits. Contestants don’t wear hairpieces, cupcake gowns, or false teeth, known in the glitz trade as “flippers.” For the pageant this year, pandemic masks were mandatory offstage, and the audience was limited to immediate family. The winners serve as industry ambassadors during their yearlong reign while attending community events — the Georgia Peach Festival in Fort Valley, a Peaches & Politics rally sponsored by one of the “big four” farms, the District 8 GOP fish fry, even the Peach Blossom Cluster dog show. According to certified judge and board president Donna Long, the girls receive invitations for all sorts of things related to peaches. The pageant is also a gateway to bigger competitions. Two peach queens have gone on to win the Miss Georgia title.

“How do you keep the tiaras on their heads?” I asked, sipping peach ice tea with the queens and their mothers at the Peach County Historical Society luncheon.

“See these clips?” said Long, holding one up. “We take pantyhose and thread it through holes in the base before we crown them. So when you put it on, the snap clips got something to attach to.”

“Pie or cobbler?” I asked.

“Pound cake.”

Tiny Miss Georgia Peach Ava Carpenter shows off her bracelet. Memorabilia from the Peach Blossom Festival, first held in 1922, on display at the Peach County Historical Society.

Having changed into “It’s a Fuzzy Thing” festival logo T-shirts, the girls poked at their plates of chicken salad. Took selfies. Shared concession stand candy and kettle corn from the midway. Their mothers talked about the cost of pageants, hair and makeup artists. Tiara carrying cases. Favorite couture knockoff seamstresses and the brisk trade in secondhand evening gowns. Dorsey’s mother, Tanisha, a former pageant queen herself, operates an online clothing boutique.

Is a fruit queen any different from head cheerleader or debutante? Maybe. Peaches and feminine beauty have been conflated across cultures since the Taoist legend of Xiwangmu, Queen Mother of the West, who tended the Peaches of Immortality in her palace garden and decided which gods would be permitted a taste of the fruit that granted life everlasting; she hosted the chosen at an elaborate banquet known as the Feast of Peaches. Mystic peaches aside, what about the mundane kind baked into a giant soupy cobbler? Easily the subject of far too many sexy love songs. Search for Georgia+peach+lyrics and it gets raunchy fast.

Sydney Dorsey knows about body image. The reigning peach queen was awarded additional titles for prettiest dress, smile, hair, and eyes. But pretty girls can be bullied, and after her freshman high school year, Dorsey switched to home schooling.

“There’s not a lot of [body] positivity in my county,” she said.

When you wear skintight gowns, ample curves can receive comments by judging panels. And they’re not always kind. Stubbornly upbeat, she cited model and size-acceptance advocate Ashley Graham as inspiration.

“That's the thing about pageants, as my mom reminds me, it’s just a set of opinions on a certain day.”

The court returned to mingle on the midway. A little girl with hair tied in bunches stopped Dorsey at a lemonade stand and begged for a pose, face flushed with excitement to be close to a real queen. As Dorsey bent to give her a hug, the mother caught the moment on camera.

“What’s your daughter’s name?” I asked.

“Scarlett.”

Little peach queens Jessa Grinolds and Ava Carpenter on the midway.

Several days later, back home in Swainsboro, two hours east of Fort Valley, Dorsey showed me her collection of tiaras. She has over 100, some mothballed in storage, the most ornate displayed in a converted gun case painted white and gold. In a hallway off the family room, she opened the glass door for a better look at the trophies, satin sashes, and rhinestone crowns.

“This is my shrine,” she laughed.

“What is Miss Real Squeal?”

“A barbecue festival pageant.”

Her path in pageants, as Dorsey explained, started as a baby. She has reigned as Teen Miss Southeast Georgia Soapbox Derby, Miss Uvalda Farm Festival Queen, UNM Georgia Teen, Miss Tattnall Shrine, Pinetree Festival Queen, Teen Miss Peach State. Her biggest win, Miss USA National Teen, came with a $140,000 prize package. This year is her second go-round as a peach queen; in 2018, she held the title of Teen Miss Georgia Peach.

“I'm a big festival girl,” she said, straightening the sashes in the case. “And I love [organizers] Miss Donna and Miss Diane. They continue to follow your journey, whatever it may be. It's not like you give up your Miss Georgia Peach crown and you never hear from them again.”

Dorsey learned hair and makeup with YouTube tutorials, and practiced on her pageant friends. In the fall, she’s enrolled to study cosmetology at Southeastern Technical College, and then her mother will help set up a hair salon in town. Their boutique operates out of a spare bedroom in her parents’ brick-and-clapboard ranch. Her gowns were temporarily hung between racks of casual wear they sell at pageant pop-ups.

“Red is my power color,” she said, unzipping garment bags to fluff silk and chiffon dresses.

One had sheer side panels and a train.

“This is my baby. I wore it at Miss Georgia Peach.”

A costume feather headdress hung on one of the racks.

“I don't know why this is in here, but I have Cherokee heritage.”

“You do?”

“On my mom’s side. For one of my senior pictures, I wore this with a black bodysuit and jeans.”

She tucked it away.

“You seem to have a clear vision of what all this can do.”

“Yes, ma’am. But a lot of people think it's girls prancing in fancy dresses, and there's definitely a stigma around it.”

“People make fun because you're in pageantry?”

“You can get on social media, especially TikTok, and they'll make fun of girls onstage or, you know, talking on the microphone, announcing who they are and where they're from.”

“Well, that sounds like more bullying.”

“My first year of college was completely paid for through the pageant scholarships I've earned. That alone should just make people zip it.”

Miss Georgia Peach Sydney Dorsey in her winning pageant gown and tiara.

Dorsey walked into the kitchen, where her pet chaweenie, Ellie, demanded our attention. The peach queen flipped open an album and pulled out a childhood snapshot. A heart tiara tangled in her hair, she held a bouquet while perched next to a trophy.

“This is baby pageant me.”

“How was that giant peach cobbler, honestly?”

“Well, my grandma makes the best cobbler,” Dorsey said. “I know to go over to her house with a bucket of ice cream.”

Before leaving, I opened my phone’s music app.

“Have you ever heard of the Allman Brothers Band?”

She looked at me blankly.

“They produced an album called ‘Eat a Peach’ in 1972.”

Dorsey listened to the final track, Duane Allman’s acoustic guitar duet “Little Martha,” which he reportedly composed after a vivid dream about Jimi Hendrix teaching him the melody in a motel bathroom. The song’s namesake, Martha Ellis, was a 12-year-old girl who died in 1836. (It was also the nickname of his girlfriend Dixie Lee Meadows.) Visitors still tuck flowers in the stone hands of little Martha’s memorial statue at Rose Hill Cemetery.

“Almost sounds like something you would hear in a Lifetime movie,” Dorsey said.

If you don’t like my peaches, don’t shake my tree.

— Shirley Jackson, in a letter to her neighbor Mrs. White, July 24, 1957

“Did you eat a peach?” asked my husband.

“One or two.”

“I meant in Macon.”

Now would be a good time to admit that Bronson and I attended the farewell concert at the Beacon Theatre in New York City, one of the Allman Brothers Band’s favorite residencies over its long touring career, just before Gregg came back home to rest beside his older sibling. The final encore on the set list that night in 2014 was a cover of Muddy Waters’ “Trouble No More.” A live recording of the song from the original Fillmore East sessions was included on “Eat a Peach.”

So here at the end, parked under a loblolly pine between the shrine to the Allmans and those Confederate graves, I scrambled for a seat peach of my own. Might have been from Pearson, or UGA, or Clemson, or any of the roadside stands in between; not really sure, because by then quite a few rolled around in the back of the car, escaping their paper bags after jolting from Seneca to Swainsboro. The peach juice dripped on my last clean shirt. Then the pit flew out the car window. Maybe a feral will grow in the peaceful confines of Rose Hill Cemetery.

Can someone please name a peach for Skydog? And Sydney Dorsey, too? Until that happens, let’s relish this passage from naturalist James Alexander Fulton, who wrote Peach Culture (1870), a baseline textbook on the stone fruit that has come to define the often terrible but persistent beauty of the South.

It ripens in perfection only in the glow of a midsummer’s sun; and the hotter the weather, the more delicious are its rich cooling juices. It is eminently suited to the season. When the weather is so hot that even eating is a labor, the peach is acceptable, for it melts in the mouth without exertion.

It is the Queen of Delicacies.

That’s a title worth a tiara.

Shane Mitchell has received three James Beard Foundation awards for stories about problematic crops and food insecurity. “The Queen of Delicacies” is the seventh installment in her Crop Cycle series for The Bitter Southerner. She still hates grits.

Amanda Greene is a photographer and artist living near Athens, Georgia.