The world we want and need isn’t one we have lived yet. Memphis taught a photographer that we all play a role in our collective narratives.

Words & Photos by Andrea Morales

On the evening of April 3, 1968, an intense rainstorm shook the windows of the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee. Thousands sat in the auditorium seats as thunder clapped, lightning struck, and the wind blustered. The city’s sanitation workers, a largely Black workforce, had been on strike for nearly two months after Echol Cole and Robert Walker were killed on the job on a rainy day in February of that year. The strike called for safer working conditions, better pay, and a union. Henry Loeb, the white mayor of a city with a large Black population, met these demands with contempt. The workers and others had gathered at the temple ahead of a planned march the next day.

The workers’ fight had drawn the attention of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who traveled to Memphis in support of the strike. He had been organizing across the country as a part of the Poor People’s Campaign, what he called a “revolution of values” with the goal of building lasting power for the poor. What was happening in Memphis was not a formal part of this, but King supported the workers and fellow ministers, such as the Rev. James Lawson, in the fight for economic and racial justice.

King stood at Mason Temple’s pulpit on that stormy April night and delivered one of the most historic speeches of the 20th century. “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” is known for its sweeping, powerful, and evocative calls for a future defined by what he had seen in the Memphis strike: a powerful challenge to racism through organizing by the working poor and a successful coalition of Black people across class.

“Something is happening in Memphis, something is happening in our world,” King said.

Being the experienced preacher that he was, parables spun into punchlines and excitement inspired ecstasy as he spoke about the power of the boycott while reflecting on the successes that nonviolent civil disobedience brought to Black people in America. He evoked one of his favorite prophets, Amos, whose writings boldly denounce the oppressive and unjust systems that target the poor and extract from abundance.

“Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream,” King proclaimed as a call to action.

Memphis sanitation worker Cleo Smith (at left) stands near a street sign honoring the work of the city’s sanitation workers in the 1968 strike. Smith was one of the workers who went on strike then.

As the storm intensified outside, he spoke about the real threats faced in challenging white supremacy. Constant threats were aimed at his home and family; he’d been jailed in Birmingham and other places and attacked elsewhere. The images of violence against Black people standing up against the racism of the country were prevalent reminders of what the response to resistance would be.

“Few of the people in that room felt any certainty about the future, but now the preacher and his followers moved together beyond the harsh moment of Memphis to some higher, biblical truth,” historian Michael K. Honey wrote about that evening at the temple in his book Going Down Jericho Road.

King’s voice came to a tremble toward the end of the speech and, as Honey wrote, “water came to his eyes, revealing not fear, but a transcendent hope.” In the 53 years since its delivery at that pulpit, the “Mountaintop” speech is remembered as a piece of prophetic oration. We know now that the following day, King was assassinated, struck by a fatal bullet while standing on the balcony at the Lorraine Motel in downtown Memphis.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life,” King said as his speech drew to a close. “Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

The passion was so urgent, King had to be caught as he stepped away from the pulpit and helped back to his chair. “Pandemonium swept Mason Temple as people came to their feet — applauding, cheering, yelling, crying,” Honey wrote. “Just as King appeared to have been transported to some other place, so were they.”

In 1989, my family and I migrated to the United States from Lima, Peru. Our country was experiencing a difficult chapter in its prolonged relationship with neocolonialism and globalization. Inflation was high, and social and political unrest made daily life difficult and sometimes dangerous. I was only 4 when we moved, so these stories are partially based on memories and partially based on stories I was allowed to know. I believe my parents thought they were protecting me from narratives that revealed something too frightening or too complicated.

In retrospect, the liminal space we occupied in the first few years after our arrival in Miami served to light a fuse. We moved in the quiet immigrant networks that scaffold a cosmopolitan town. Stories here sometimes serve as a liability rather than a commodity. We overstayed our visa and that requires discretion. So I became a citizen of the books and television that came in a language I was learning quickly. I raced to learn English because I thought then I could start making my own stories in the quiet of my own life.

I thought words would be my medium, but when I realized my English was still more Spanglish than anything by the time I left for college, I learned there were other ways to tell stories. When I arrived at photography as my language for this, I thought it was inherently rooted in truth because I was witnessing through a lens. I learned, in a much slower way than I learned English, that there is a whole lot that goes into who gets to hold the lens.

When I arrived in Memphis in 2014, I came with a set of ideas about the place historically and culturally, and I set out to illustrate some of those assumptions (many rooted in pathetic tropes about Graceland and fallen Kings). The community, familiar with struggle and exceptionally generous with grace, corrected me while welcoming me in to listen, to unlearn my tendencies for interlocution that my training as a journalist had afforded me, and to embrace collaboration.

A city-sponsored event pays tribute to the 50th anniversary of the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis.

Memphis taught me that we all play a role in our collective narratives. For example, in 1956, photographer Ernest Withers and writer L. Alex Wilson covered the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott for the Tri-State Defender, a Black newspaper in Memphis. Preston Lauterbach, the narrative historian who wrote a book on Withers called Bluff City, also noted that in the process of their work, the two men inadvertently became the first Black men to ride at the front of a Montgomery city bus. Their work was an act of courage, and after they dispatched their experiences back for publication, that edition of the Tri-State Defender sold out in Memphis. According to Lauterbach’s book, a group of white citizens bought all the papers in town and dumped them into the Mississippi River.

The power of a narrative can be so mighty that those threatened by it would drown it beneath a river’s charging currents. When the Lorraine Motel, where King’s life was extinguished, became the National Civil Rights Museum, it was worth questioning our own complicity in convenient narratives.

“Photography, of course, always shows us history as content: every image is in some sense a representation of a moment in the past,” Grace Elizabeth Hale wrote in an essay about the medium as history in the U.S. South. “But photography can also show us history as form — how the past gives rise to the present and sets up the possibility of the future.”

The world we want and need isn’t one we have lived yet. Memphis has portals to this world that allow us to feel this, rather than see it, because of its complicated history as well as what Zandria Felice Robinson calls the “real museums” of the city: its elders.

On April 3, 2018, heavy rains fell once again in Memphis on the eve of the 50th anniversary of King’s assasination. Thick humidity clung to the media tents outside Mason Temple where I was gathering myself after a long day. While international attention on Memphis upheld the narrative of the past as something behind us, members of the community had spent the morning and afternoon organizing protests across town to counter that notion.

One protest was directed at FedEx, whose international headquarters in Memphis enjoys significant tax breaks. It also maintains a low-wage labor force. A caravan of more than 20 cars stopped on Tchulahoma Road outside an employee entrance, blocking traffic to hold space, dance, and wave signs that read “Things Are Not OK.” Another protest was staged outside the county criminal justice center to press on the issues of bail and collaboration between local law enforcement and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Nine people were arrested, including one of my colleagues, Manuel Duran, a journalist who was reporting at the time of his arrest. He would spend more than a year in ICE custody as a result.

“Churches themselves are places of return,” Hale writes in her essay “Signs of Return.” “... By going back and looking at something again, maybe we can see where it all went wrong. Maybe we can unwind it. Maybe we can pinpoint that one essential and probably photographed moment, return to it, and then move forward again in a different path.”

In March 2018, a wreath commemorates where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot at the Lorraine Motel. It’s now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum.

The 50th anniversary event at the temple was meant to evoke and honor the spirit of that evening when King delivered the “Mountaintop” speech, but this time with a guest list of dignitaries, lighting design, and an official program.

In the front row were eight of the surviving men who participated in the 1968 sanitation strike. They were dressed sharply and had been treated like celebrities throughout the week. A few of them, like Elmore Nickleberry and Cleo Smith, still worked shifts as sanitation workers.

It took Loeb, then the Memphis mayor, about two weeks after King’s death to reach an agreement with these workers. The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, was recognized as their union, some changes to their working conditions were made, and the workers received a slight raise to their low hourly wages. Jim Strickland, Memphis’ current mayor, announced in 2017 the city would award the surviving sanitation workers a grant of $50,000 each that year, $1,000 for every year since King’s death.

A few seats down from the workers, two of King’s children, Bernice King and Martin Luther King III, were present, visibly uncomfortable as photographers knelt at their feet, snapping at the hems of their personal space. It was clear that for all the hope the program was performing, it was a painful moment for them. They kept their heads bent toward their laps, so I kept my camera tucked into mine.

“As I look at the landscape of our world today, America may still go to hell,” Bernice King said from the same pulpit where her father had stood while a storm pelted raindrops on the roof of Mason Temple. Scanning the sanctuary, I raised my lens to make a photo that is very straightforward (a speaker behind a podium) but felt like it traced a circle. “Fifty years later,” she said, “I’m here to declare and decree not only must America be born again, but it’s time for America to repent.”

This story was published in Issue No. 1 of The Bitter Southerner magazine.

Andrea Morales is a documentary photographer and journalist that was born in Lima, Peru and raised in Miami, Florida. Her personal work attempts to lens the issues of displacement, disruption and everyday magic. Adding glimpses of daily life to the record is central to how she makes work. While earning a B.S. in journalism at the University of Florida and an M.A. in visual communication at Ohio University, she worked as a photojournalist at newsrooms like the New York Times and The Concord Monitor. She is currently a producer at the Southern Documentary Project, an institute of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi and the visuals director for MLK50: Justice Through Journalism.

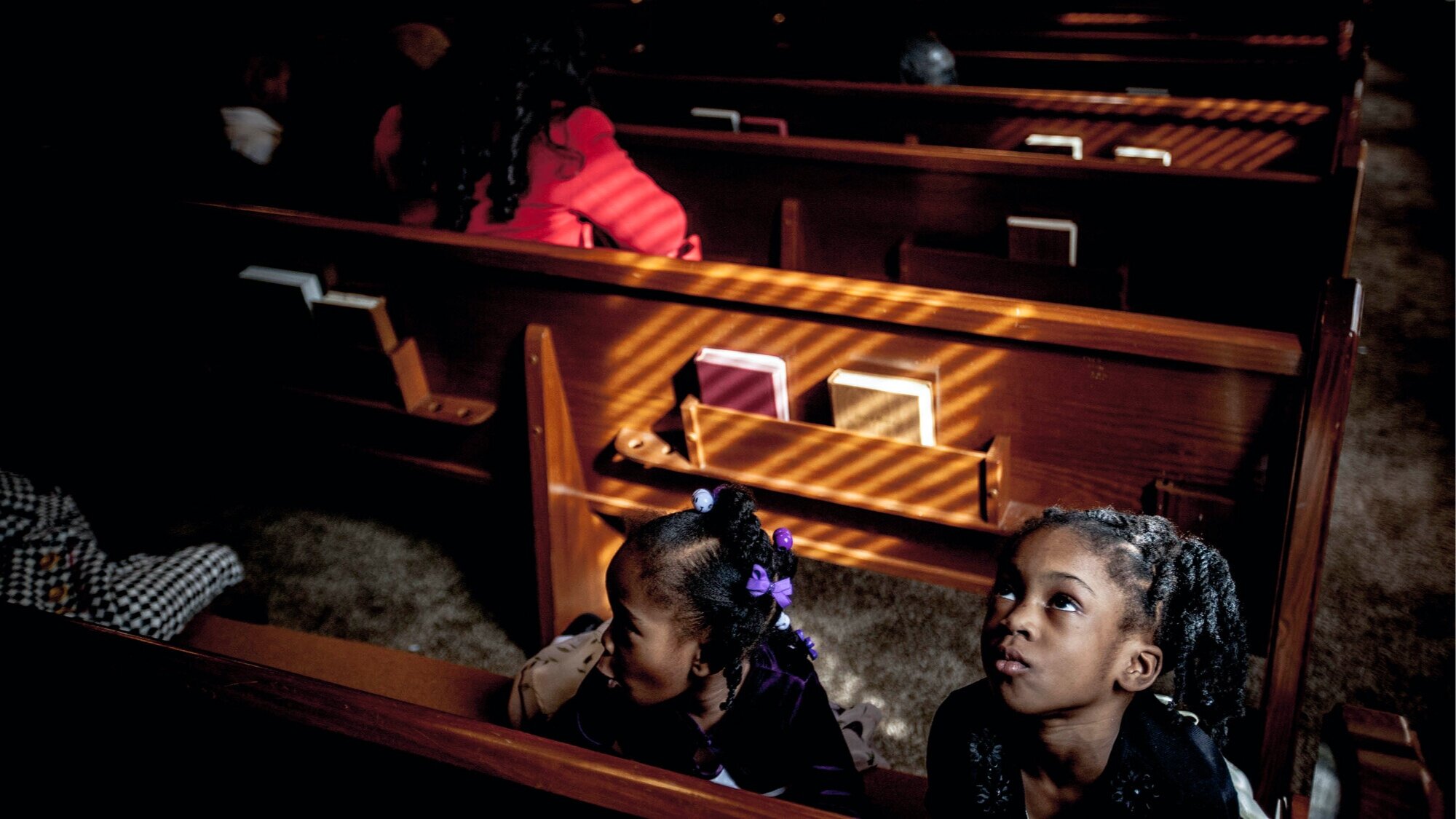

Header photo: Kaylin McCain and Jakayla Davis wait for their grandmother to sign up for the Affordable Care Act at Impact Baptist Church in Frayser, a Memphis, Tennessee, neighborhood, in February 2015.