Chris Owens danced in her French Quarter nightclub for 66 years. Her defiance of time and over-the-top style made her an icon, beloved by a surprising cross-section of New Orleanians and visitors.

Story by Jordan Hirsch | Photos Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection

December 1, 2022

When Chris Owens died in April, it felt a little untoward, and somehow reductive, to say she was 89 years old. The Queen of Bourbon Street remained famously mum about her age, and for half a century media coverage of her had deferentially sidestepped it, focusing instead on her enduring appearance and energy — “statuesque” and “vivacious.” She’d been doing the cha-cha in her French Quarter nightclub for so long that no one seemed to recall when she started, and in any case New Orleanians were invested in the legend of her timelessness. Even as portable neon drinks became Bourbon Street’s main draw, Owens’ staying power offered some assurance that the modern tourism industry hadn’t steamrolled the version of the city that preceded it, and that a bold sense of self could conquer all.

Owens made her name dancing in form-fitting, glittering outfits of her own design — which, she often pointed out, stayed on throughout the show, lest anyone get the wrong idea. But most New Orleanians under 50, like me, knew Owens not from her act but her celebrity, as a staple of the society pages and local television, and Grand Duchess of the annual Chris Owens French Quarter Easter Parade. For most of my life, one of the comforts of returning home from a trip out of state was being greeted by her smiling face — red lipstick, silver microphone, tidal wave of black hair — on an advertisement in the airport that, like Owens herself, shone in the same spot for decades. Jokes about her age were ubiquitous, but not mean-spirited; most of us hoped, and some assumed, that she would shake her maracas in perpetuity. It was only after Hurricane Katrina impressed on me that nothing in New Orleans would last forever that I went to see her perform at her namesake club.

Two promotional photographs of Chris Owens.

For my first visit I made a reservation, an exercise less about ensuring the availability of a seat and more about building anticipation. A sign permanently announcing “Chris Owens” in blue neon hung over a low-rise stage in the corner of the room with a few tables radiating from its edge. Colored lights pinged off reflective surfaces everywhere.

Owens came out beaming, backed by a full band, neckline plunging, hemline reaching for the heavens, hitting some athletic dance steps and throwing an arm in the air. The repertoire was current, including a spirited rendition of “Save a Horse (Ride a Cowboy),” but the showmanship was classic. At one point she winked and whipped me a hot pink matchbook emblazoned with her image. I was delighted, and mystified by where she’d been holding it.

Owens lived directly behind her club, in a custom-built townhouse that she revealed to the public in magazine spreads, television segments, and during the occasional home tour event. She told The (New Orleans) Times-Picayune that her design aesthetic was “glamour, pure glamour,” manifested in marble floors, mirrored walls, an enclosure for white doves on the patio, and an “opulent boudoir, with a striking flowered carpet created to pick up the colors of her headboard.”

The stage was an extension of the world she’d built for herself. Or maybe her life was an extended performance. Either way, she enticed her audience to come inside her reality, fostering the hope that you could make your own world once you finished the visit. As playwright Lisa D’Amour said in 2015, “When you are around Chris, she makes you feel like you can do anything.”

Owens reigned as New Orleans royalty but appealed to the masses, a trait that set her apart from the city’s traditional aristocracy. On Mardi Gras, while elite Carnival krewes held private balls, Owens perched herself on her club’s balcony, looking fabulous for the Bourbon Street crowd and the cameras. A lotus blooming from the muck below — unsullied by it, but nurtured from it, too.

***

Chris Owens inside her French Quarter home in 2014, taken for the New Orleans Life Story Project. (Photo by Keely Merritt)

For as long as I can remember, Owens has been celebrated as a paragon of self-determination, but that’s not how she started her career. Born on a West Texas ranch during the Depression, she was working in a New Orleans doctor’s office in the early 1950s when she caught the eye of Sol Owens, a wealthy car dealer and bon vivant. He told her, “Kid, you do as I tell you and I’ll drape your shoulders with mink.”

They each held up their end of the bargain. She turned heads when the couple went dancing, including visits to the Tropicana in pre-Castro Havana, where she started appearing in shows. In 1956, Sol bought a club at 809 St. Louis Street, just off Bourbon, and she drew crowds as a performer. In those days, Bourbon Street was a plausible feeder to mainstream show business, and Owens fielded interest from Hollywood and Broadway. But, “Sol, of course, handled my career,” she would later explain to OffBeat Magazine, “and we opted to stay here.” Sol thought children would cramp their lifestyle, and Owens said she was fine with not having any. They’d periodically shut down the club to go party in Paris or some exotic port of call.

Sol also shaped his wife’s audience. While Owens danced to Black Caribbean music, she began performing exclusively for white crowds. The 809 Club was segregated by law until the 1960s, and, like many clubs on Bourbon Street, continued to discriminate for years afterward. In 1976, Sol told a reporter, “Oh, we got nothin’ against well-dressed Blacks, but everybody gets a subtle screening at the door, you know? If they don’t look like our kind of people, we just gently discourage them.” (Practically all accounts of Owens’ heyday omit this racism. A feature in The Times-Picayune from 1996 invoked Bourbon Street’s “genteel past.”)

In 1969, the club moved to a huge building Sol bought at the corner of Bourbon and St. Louis streets, the performance space “complete with zebra upholstery.” It was later renamed for Owens, its main attraction, though she still demurred as Sol managed the business. (New Orleans) States-Item reporter Allan Katz once noted that, in the couple’s relationship, “Sol does most of the talking.” In another article for The Times-Picayune, Owens dismissed “Women’s Lib,” remarking, “The only thing I go along with is the bra-burning.”

When Sol died in 1979, Owens said later, “It was like my world ended.” But she fashioned a new one in the ’80s. By that time, tourism had emerged as the city’s only economic hope, and Bourbon Street was its backbone. The strip had transformed since Owens started out. Back then, live entertainment catered to couples in suits and dresses. Now, following the popular taste of vacationers looking to cut loose in the Big Easy, original stage acts declined and to-go drinks proliferated. In 1983, when her friend Al Hirt, the Grammy-winning trumpeter, shut down his namesake club across the street from hers due to “the degeneration of the French Quarter,” Owens dug in and ruled over the neighborhood’s Easter Parade.

As her old competition — burlesque acts like Evangeline the Oyster Girl, who disrobed after emerging from a giant bivalve with a beachball-sized pearl — gave way to modern strip clubs, Owens stuck with her PG-rated brand of titillation. Posters showing her bare legs announced a “Hot, Hot, Hot!” show, which it was, in its way. She was known for audience participation bits, like coaxing a bashful older man into a chair onstage, sitting on his lap, and singing “My Heart Belongs to Daddy.” Some locals nostalgic for old Bourbon Street might show up, or party people looking for a dose of camp — men who flew B-52s, or, one night, Fred Schneider, lead singer of The B-52s.

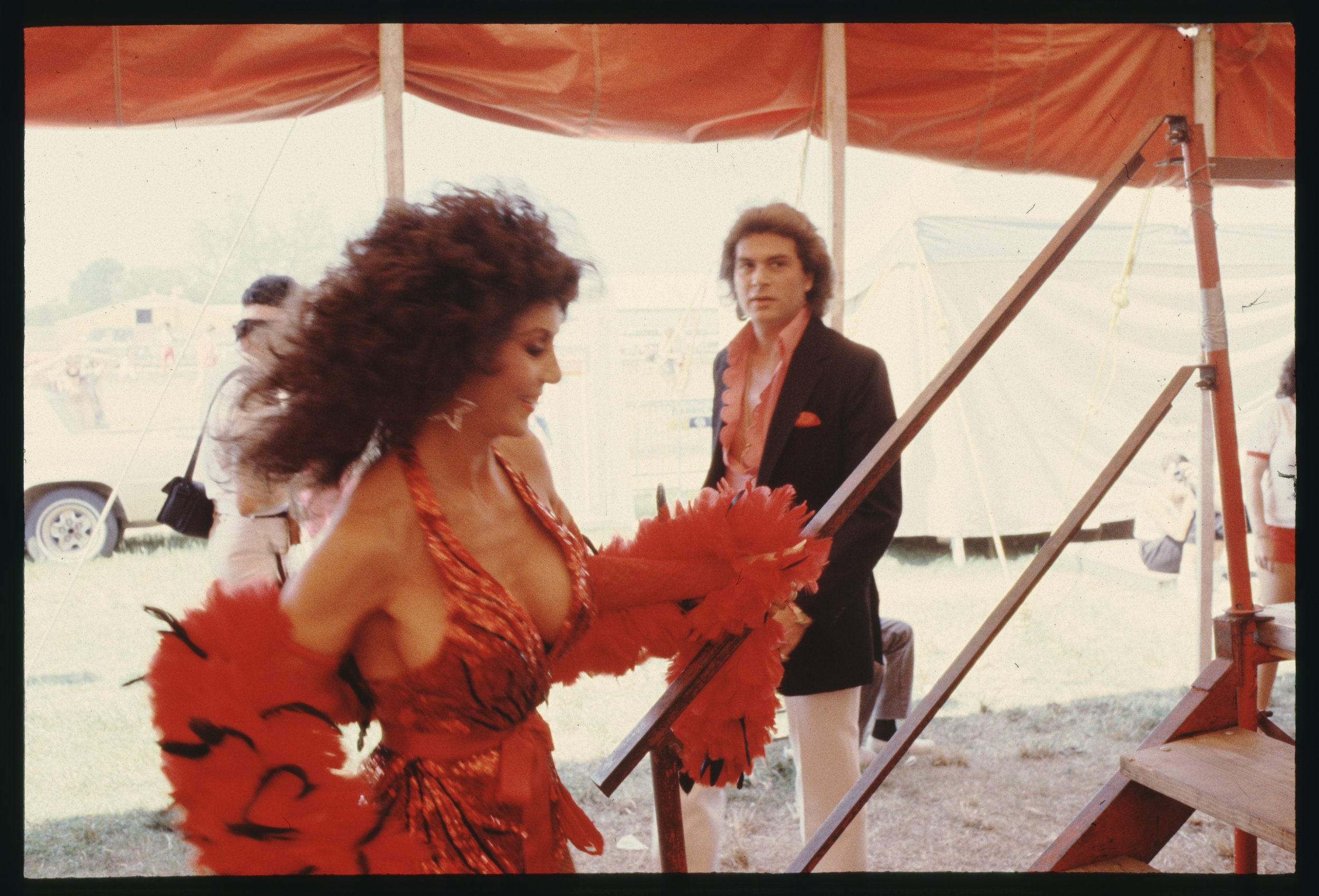

An act with staying power: Sol and Chris Owens.

Though Owens’ act became a niche, the real estate she owned on the block was gaining value. In 1991, The Times-Picayune reported that “12 years after Sol’s death, Owens manages everything — home, nightclub, 28 upstairs apartments, four rental shops, vintage Mercedes — and dominates this hive of enterprise like a queen bee.” She expanded in subsequent years, licensing a hot sauce, Chris Owens’ Bourbon Street Heat. She hired hip-hop DJs to fill the club after her shows, attracting a new Black clientele. (It took a while, but Bourbon Street eventually became the most racially diverse spot in the city.)

While Owens continued to play the coquette, her silhouette defying the years, she developed the steel of a no-nonsense landlord and club owner. I felt it myself one day in 2008 when I answered a knock on the door of my office and found myself face to face with Owens, wearing a velour tracksuit, with her hair pulled back. She was there to collect rent owed by one of her tenants, a musician. I ran a nonprofit that was helping the music community reconstitute itself after Katrina, and we had apparently made a mistake with a check mailed to her on the tenant’s behalf. Starstruck, I wanted to offer her a seat and discuss our mutual disdain for linear time, but her posture conveyed that she was there to get what was hers. She left as soon as I gave her a new check.

For most of us, the flood in 2005 represented a violent break with the past, but Owens had the wherewithal to keep doing her thing. (While 80 percent of the city was underwater, The Times-Picayune reported that she was high and dry at home, with “guns, ice and all the liquor from her club.”) Bourbon Street was the first part of town to get back up and running, and Owens hit the stage twice a night, six nights a week. Elected officials channeled recovery dollars into the tourism industry, benefiting downtown property and business owners like Owens while others struggled to recover. She was reputedly a quiet donor to worthy causes, but for me her contribution to the new New Orleans era was the way she connected it to the old one.

By the 2000s, Owens’ reputation as an entrepreneur had elevated her in the local power structure. She’d joined the business community at charity galas, recorded videos for the city’s Chamber of Commerce, and publicly supported politicos, including former Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards. At the same time, her longevity helped make her a populist hero, an aspirational figure who stayed on top without compromising who she was, her legs still drawing stares.

***

Carnival Time on Bourbon Street collage, made by Owens in 1978.

The best shot everyday people had to live like Owens was on Carnival, when we have license to wear whatever we please and let go of our inhibitions. On Mardi Gras in 2011, my partner Aimee dressed up as Owens while I went as her longtime companion, Mark Davison, and we set out for the corner of Bourbon and St. Louis.

Davison, who had been by Owens’ side for most of her public appearances for the last quarter-century, had a feathered blond mane with an accompanying mustache. Multicolor jacket draped over his broad shoulders, he looked like a former Chippendales dancer who was still partying in the 1980s. He had an air of celebrity, too, though not much name recognition. Davison quietly ensured that Owens was always the center of attention. He also underscored her everlasting youth — their relationship began in 1994, when he was 32 and she was 62 (not that most of the public exactly knew their ages). When Aimee and I got to the club, the staff greeted us with guffaws and high-fives, and posed with us for pictures under the neon “Chris Owens” sign. Walking on the empty stage, I noticed a support beam in an awkward spot. It had been made to look like a stark white palm tree, a structural necessity turned into a surreal piece of set decoration that blended into the décor.

Eight years later, we went to a Carnival ball in a suburban theater where Owens and Davison reigned as the king and queen of the Krewe of Stars. The curtain lifted on them to the recorded strains of “Also sprach Zarathustra.” That segued into a jazzy shuffle by a live band as the couple made their way to two thrones at the edge of the stage, resplendent in white and silver, she with a soaring Medici collar and mantle, he in a cape, both with crowns and scepters.

Afterward, Owens and Davison emerged in the lobby — wearing a different gown and suit — and posed for pictures with fans. For the first time I’d seen, Owens had the bearing of an older person — fragile, not quite steady on her high heels. Davison, who’d held her hand from his throne, may have clocked it, too; they left after a few minutes. Having lost my father the year before after a prolonged illness, Davison’s devotion struck me as noble — choosing a partner 30 years his senior, knowing he’d be a caregiver at the end of her life and reconciling himself to living a long time without her.

But three months after the ball, it was Davison who died: liver failure at age 57. I couldn’t think of anything sadder than Owens, at 86, having to bury him. Three days after he was buried, she led the Easter Parade as scheduled, in a white bustier and oversize white hat with Day-Glo flowers on the brim, her name in quotation marks behind her on the title float.

The next two parades were canceled due to the pandemic, and though Owens returned to the stage when restrictions on indoor gatherings lifted last year, I didn’t see her perform again before she died. Her funeral was a week before this year’s Easter Parade, which rolled in her honor following a silent prayer and dove release.

Chris Owens poses in her dining room. (Photo by Keely Merritt)

An estate sale was announced online in June. Scrolling through pictures of the offerings, Aimee spotted a framed portrait of Davison. The doors would open at 8 a.m. I would ride at dawn.

The first person in line, Hannah Joffray, got there at 4. Two friends met her with orange juice and champagne in an antique ice bucket to mix sidewalk mimosas. As the drag performer Visqueen, Joffray co-created Choke Hole, a drag wrestling show that has become an underground sensation since its 2018 inception. She was there to buy some of Owens’ fur shawls to incorporate into one of her acts. It would be a fitting succession. Owens inspired generations of drag performers in New Orleans, as well as a burlesque revival that gathered steam in the 2000s. Her self-invention and maximalist style made her an outré icon.

Farther back in line, Mary Massengill told me more about Owens’ special standing in the city’s LGBTQ community. In the early ’80s, Massengill had to be careful going to lesbian bars because the license plates of cars parked nearby were sometimes reported back to the military, where she had to serve in the closet. Then, word spread that Owens’ club was a safe space, somewhere Massengill could go and be herself without looking over her shoulder. On any given night people showed up in drag or costume, and Owens welcomed them all. When Massengill got married, the first thing she and her wife did as an out couple was hit the Easter Parade in pastel polo shirts. “We’ve come so far,” she said, “and Chris was such a big part of it.”

Another woman, Shari Sinwelski, was carrying a copy of a book she’d made, Everybody Wants To Be a Queen. It was about her pursuit of Owens’ signature on an exquisite Chris Owens doll made by the drag performer and artist Vinsantos. Sinwelski is from Florida but fell in love with New Orleans, and Owens was one of the reasons why. “She inspires me,” Sinwelski said. “Just the way she lived her life, [doing] whatever she wanted to do. That’s my dream.”

At 8 a.m., the first 30 people entered. I was the 31st, and had the door politely closed on me. Then opened: It was so hot outside, the next 30 could wait in the air conditioning. To make room for people behind me, I walked through a showroom of furniture to a cordoned-off area holding the Owens bounty: leather recliners, candy-colored martini glasses, Chinese vases, Thai lion bookends. In the distance, Owens’ voice, from one of her records, sang ABBA: “If I had to do the same again / I would, my friend, Fernando.”

And then, a gift: I was waved inside. While Joffray and a dozen others busied themselves around a rack of Technicolor coats, I spotted the portrait of Davison in a far corner. It was bigger than I expected, over 3 feet tall. When I got close, I saw it wasn’t a painting but rather a blown-up, glaringly pixelated photograph. Even better. Davison and Owens had made themselves larger than life, beyond the limits of bourgeois aesthetics. I had to heft it off the wall — the frame, ornately patterned gold, weighed a ton. I paid and left in a rush, before my luck could run out. The previous day Aimee had looked around our apartment, musing about where we might hang it. I said it didn’t matter. It would look great everywhere, always.

Jordan Hirsch is a writer in New Orleans, his hometown. He edits the interactive map of the city’s music history at ACloserWalkNola.com.

Header Image: Ever flamboyant and faithful to her audience, Chris Owens, bounds onstage at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 1986. (Photo by Michael P. Smith)