Live auctioneering is a dying industry, with the pandemic pushing even more auctions and sales to online platforms. But professional auctioneer Eli Detweiler’s clear, precise, concise chant is performance art: massaging listeners to dig deeper for money they hadn’t planned to spend.

Story by Jarrett Van Meter | Photos, Video, and Audio by Kate Medley

It’s 9:50 a.m., 10 minutes before showtime, the temperature has already topped 80 degrees, and Eli Detweiler Jr. is sweating. Watching farmers inspect the tractors that he will soon sell, he knows the day will get hotter. It’s already noisier, as prospective buyers crank up three McCormick Farmalls, a blue Ford 5000, and a John Deere 4430. The caps of their exhaust stacks clap like syncopated cymbals.

This is a goodbye auction for the Hepler farm, which has been run by the same family since the 1930s. Detweiler is an expert auctioneer hired to manage the sale of farm equipment and tools as well as antique furnishings and household appliances. Nearby farmers have brought a few items to be sold on consignment, but almost everything belongs to the Hepler family.

There is a hand-crank washing machine from the 1930s and a vintage cider press, metal livestock gates speckled with rust, and handmade quilts tented over the tops of ladders so their intricate patterns can be admired. These are the fading remnants of a time when artistry and craftsmanship were prized by farmers who also knew how to pivot when the larger marketplace changed.

Brothers Charles Larry and Robert Hepler, third-generation owners of this 38-acre farm in Thomasville, North Carolina, know what “adapt or die” means. Their family originally raised dairy cows and sold milk, then switched to beef cattle, and finally left the livestock business two decades ago to grow soybeans, hay, and corn for sale.

Now the fields are fallow and the grim reaper of urbanization looms over the far fence. Neighboring farms have been replaced with residential developments and a golf course. New owners will take over the Hepler land with plans to build houses, condos, and a grocery store. Everything goes today: This is a total liquidation sale. Many are leaving the farming business, says Charles Larry Hepler, sitting on the open tailgate of his pickup. “You can’t make no damn money.”

The Heplers are part of an exodus that is happening throughout the United States. In 1935, there were 6.8 million farms in the U.S., but in 2020, that number had dropped to 2 million. About 6,000 farming operations in North Carolina have shut down since 2007, leaving 46,000 still in business in 2018. Auctioneering, which brings music and rhythm to the sale of just about anything, animate or not, has experienced a similar decline. In 2000, when big tobacco switched from live auctions to fixed contracts with growers, North Carolina had 2,500 licensed auctioneers. Today, there are 1,800 in the state, director and past president of the Auctioneers Association of North Carolina Bill Forbes says. Membership in professional associations is shrinking like a farm pond in a drought, and the future of the craft is unclear.

Detweiler has a boot planted in each of these changing worlds. He is an expert when it comes to selling farms left behind by economic change. He grows hay and raises cattle on 140 acres in Ruffin, about an hour’s drive north of the Hepler farm. He knows the differences between steel and fiberglass T-posts, what Larry’s Farmall Super M is worth, and what the John Deere 4400 combine should bring him today. The Heplers hired E.B. Harris Inc./Auctioneers, and they, in turn, brought in Detweiler to manage the day’s proceedings. Although he’s mostly an independent auctioneer, Detweiler occasionally takes on management gigs like this one for other outfits, visiting the site ahead of time and uncovering saleable items like old wagon wheels or antique plows. He wants to bring in as much as possible for the customer, which also means his commission for the day will be higher.

Just before the 10 a.m. start time, Detweiler puts on his sunglasses, dons a cap with an E.B. Harris logo, wets his whistle, and limbers up with some tongue twisters.

The handle goes up, the hammer comes down.

Let a little in, let a little out. Let a little out, let a little in.

Detweiler, E.B. Harris, and two helpers mount the flatbed trailer, and buyers gather round. Wearing Wranglers, boots, a white oxford shirt, and a red necktie, Detweiler looks like a country preacher. Nobody tops Detweiler as a bid caller, but Harris is the day’s emcee. He takes the microphone and greets the in-person crowd before turning to the proverbial elephant in the room staring down at the action from the truck bed. It’s a webcam.

“All you folks on the internet, thank y’all,” Harris calls out in his Foghorn Leghorn voice. “Thank y’all for being here. Wherever you are, if you’re sitting at the kitchen table, or you’re in your shop, in the tractor, at the beach, thank ya for being here.” Today, the internet is the auctioneer’s friend because it brings in more bidders. But virtual marketplaces like eBay and Copart are gradually making live bid calling irrelevant, an effect that was only exacerbated by the Covid-19 shutdown.

Harris jumps down from the truck, and the game is on. He auctions off the first few items from the ground as the other three hoist them high from the flatbed. A few items in, in the midst of selling a brass-tagged rabbit feeder, he stops.

“Y’all take a mental picture of what y’all are seeing today,” Harris says. “These are getting fewer and farther in between, farmsteads like this, now.”

Then he goes right back to calling bids.

Birdman Simmons of Halifax, North Carolina, puts forth a bid for a school bus at the auction.

Some boys fall in love with trains, trucks, or baseball. Detweiler was beguiled by auctioneers. He grew up in a large Amish family and accompanied his dad to livestock auctions, where they bought cows to milk and horses to work the fields and pull the buggies. He was entranced by the music and rhythm of the auctioneer’s chant, and soon he was riffing on what he’d heard while milking cows or chopping row crops. His uncle lived one farm over, and when he heard the chant, he knew which Detweiler boy was doing chores that day. After church on Sundays, a young Detweiler would stage pretend sales, casting his 13 siblings as buyers or sellers. He was always the auctioneer.

He was 10 when his family decided to auction their 140-acre farm in Iowa and move to a 320-acre parcel in Wisconsin. The auctioneer was Howard Buckles, whom Detweiler remembers as towering above him. By that time, Buckles had already served a term as president of the National Auctioneers Association and won two state auctioneering championships. Buckles had a strong, clear chant. Detweiler knew excellence when he saw it and resolved to become an auctioneer as good as, if not better, than Buckles.

The problem was that auctioneering was a forbidden profession in his Amish community. So was singing country music, the other dream Detweiler harbored. For 18 years he worked quietly and earnestly on the family farm, honing his chant in solitude. In July 1992, when he turned 18, he packed a bag, left a note for his parents telling them not to worry, and left the Amish community to become a professional bid caller, moving in with a friend in Coloma, Wisconsin.

When Detweiler set out to pursue his dream, the golden age of auctioneering was already over. Lucky Strike cigarettes had sponsored “Your Hit Parade” on radio and television for almost three decades, and their commercials made auctioneer Lee Aubrey “Speed” Riggs a celebrity and his sign-off phrase, “Sold, American,” inescapable. But when Congress banned broadcast advertising for cigarettes with the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act that was signed into law in 1970, the voice of auctioneering went silent in popular culture.

There were still live auctions, of course, and training schools and competitions where aspiring auctioneers honed their skills. Detweiler was untutored, untested but still determined to succeed in a field where only a few elite practitioners got by without a second job.

He found temporary work laying irrigation pipe on a nearby farm and spent every free minute cold-calling or writing job-hunting letters to auctioneers all over Wisconsin. He admitted he had not been to auctioneer school and had no formal training, but he swore he’d do anything to get into the business. A former Green Beret named Billy Bickford, who had taken up the craft after 20 years in the Army, hired him that fall. Detweiler spent the winter hauling and setting up sales, loading and carrying when they were over. He watched and learned, and practiced his chant on his own.

In March of 1993, on a cold, overcast afternoon, Detweiler stood on the flatbed truck at a farm auction similar to the Hepler liquidation sale he would preside at some 28 years later. He hoisted items high while Bickford called bids. The day was winding down and he had already helped buyers load the good pieces into their cars and trucks. Only the scraps remained, and the crowd was melting away like spring snow. Detweiler felt a hand grab his leg. Bickford was looking up at him.

“Time to sell that milk can,” he said.

So Detweiler grabbed it and held it up as high as he could, waiting for Bickford’s chant to begin.

“No, you sell it,” Bickford said.

So he did, for $7. Not only that, but Bickford let him finish out the day, selling off some tools and the contents of a few sheds dotting the property.

“People were taken aback, like, ‘Whoa, he actually can auctioneer,’ and by the second or third item, they were falling right in there, bidding on stuff,” Detweiler remembers.

Bickford helped Detweiler get a job with Wild Rose Auction and Realty Company, and less than one year later he was calling bids for antique, real estate, farm, and estate auctions run by the company. He won a novice bid calling competition in 1994, catching the eye of Jack Hines, a renowned professional who had been teaching for two decades at the World Wide College of Auctioneering (WWCA) in Mason City, Iowa. Hines offered Detweiler a scholarship to attend the school.

Hines ranks Detweiler among the top 10 graduates of the program, an intensive, nine-day course that covers everything from bid calling to real estate sale and clerking. The word on Detweiler’s chant as he was coming up was that he was too fast and didn’t breathe enough, which WWCA helped him smooth out.

More importantly, he learned to sell every item as if it were his grandmother’s.

Two men inspect a red Farmall tractor before the auction begins.

At the Hepler sale, the bidders move slowly around the house, not unlike a herd of cattle, and then concentrate when the auctioneers reach the row of tractors out back. The truck with the mounted webcam is along as well, looming over the crowd. Detweiler takes the microphone and sells the first one, the McCormick Farmall 100. He starts the bidding at $2,000.

Will you go, will ya bid? Will you bid one, will you bid two, will you bid three, who’s gonna give four?

It is performance art, massaging listeners to dig deeper for money they hadn’t planned to spend, coaxed by his powerful stage presence and the chant. Oh, the chant. Clear, precise, concise.

Detweiler rides the rise all the way to $4,200. SOLD. Then he sells another Farmall for $4,000. There’s a concession tent next to the house, and the aroma of burgers on the grill drifts over the crowd. It’s 11:30 now, the temperature nearing 90, and everyone is jockeying for spots in sparse patches of shade.

A farmer named Tom, who owns 200 acres on the line between Forsyth and Davidson counties, has come to purchase the giant Ferguson hay rake that will come up in a few minutes. He devours one, then two sausage biscuits while he waits. Tom used to grow tobacco on his farm, but now raises cattle, soybeans, hay, and corn. He lives in the part of the state now being marketed as “the Piedmont Triad,” where Greensboro, High Point, and Winston-Salem are increasingly desirable places to live. He worries that rampant development will squeeze out all the farms — like his and the Heplers’ — and turn the area into “another Atlanta.” Small profit margins keep him on a budget and he expects to pay about $350 for the rake.

~ Click images to view larger ~

After the last tractor is sold, the crowd thins and the diehards trail into the back pasture for the last of the farm equipment. Tom’s rake comes up, and the bidding zooms to $500, $600, $650. Tom goes in for $700. Going once, twice, SOLD for $700. “Well, I got what I came for,” he says, sounding resigned.

A Ford F250 pickup sells for $2,500 and a flatbed trailer for $4,000. The crowd dwindles to half a dozen people, who huddle around the remaining scraps like pigeons. The last item sold is an orphan tractor tire that goes for $3.

When Detweiler is hired solely to call bids, his favorite part of the work, he earns between $300 and $1,000 per day. He’ll take home a lot more from the Hepler auction because he was brought in to set up the sale in advance and manage the day. Neither he nor E.B. Harris, who hired him, will talk about the gross for the day or what percentage Detweiler will pocket.

“The most fun of the auction business is calling the bids,” Detweiler says. But experience taught him that the real money was in commissions that sellers pay auctioneers who set up and manage sales.

Potential bidders keep a close eye on the proceedings.

Detweiler won the Wisconsin State Auctioneer Bid Calling Championship in 1995, the year that eBay launched as the first online auction and shopping site. His calendar filled with paid auctioneering jobs, but to live comfortably he still needed to read residential meters for a gas company. His schedule was flexible enough that he began competing nationally with Jack Hines. He traveled to auctioneering competitions and conferences, and he met his future wife in North Carolina during one of those trips. Detweiler read his last meter, left Wisconsin for good, and settled in North Carolina in 1998. Two years later, he won the North Carolina state title. The marriage didn’t last, but he bonded with his adopted home.

Before he arrived, tobacco was king in North Carolina, an industry that built cities, universities, parks, museums, and hospitals — while gradually killing its customers. Since moving to the South, Detweiler has become friends with Sandy Houston, a man who was arguably the world’s best tobacco auctioneer when big tobacco companies bought sheets of dried leaves in huge, dusty warehouses. But when they started contracting directly with farmers, the auctions and the auctioneers were history. Between 1997 and 2000, 35 North Carolina tobacco warehouses closed.

“People say the auction system is dying,” Houston told the Greensboro News & Record in 1999. “I say it's been dead for five or six years. They just decided to bury it.”

Detweiler, of course, doesn’t grieve tobacco auctions like his friend does, because he’d never been part of that system. But still, they got along. The two got to know one another because they both lived in the Piedmont Triad and carpooled twice a week to auto auctions in Myrtle Beach and Darlington, South Carolina.

Twenty years later, Detweiler and Houston are best friends. Detweiler thinks his career hasn’t peaked yet, and Houston sees himself on the home stretch. Both have full schedules despite the growth of eBay, Copart, and other virtual marketplaces. These platforms have been competing with live auctions for 25 years, and the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated their growth. eBay reported more than $10 billion in revenue in 2020, nearly 20% more than the previous year. Copart, a much smaller digital platform, has also prospered due to the pandemic.

Detweiler and other auctioneers hate to talk about whether the ease of bidding online will make them obsolete. Jack Hines, Detweiler’s teacher and mentor, insists there will always be live auctions. That said, he has watched his son, Jeff, transform their 60-year-old business into a largely online auction site.

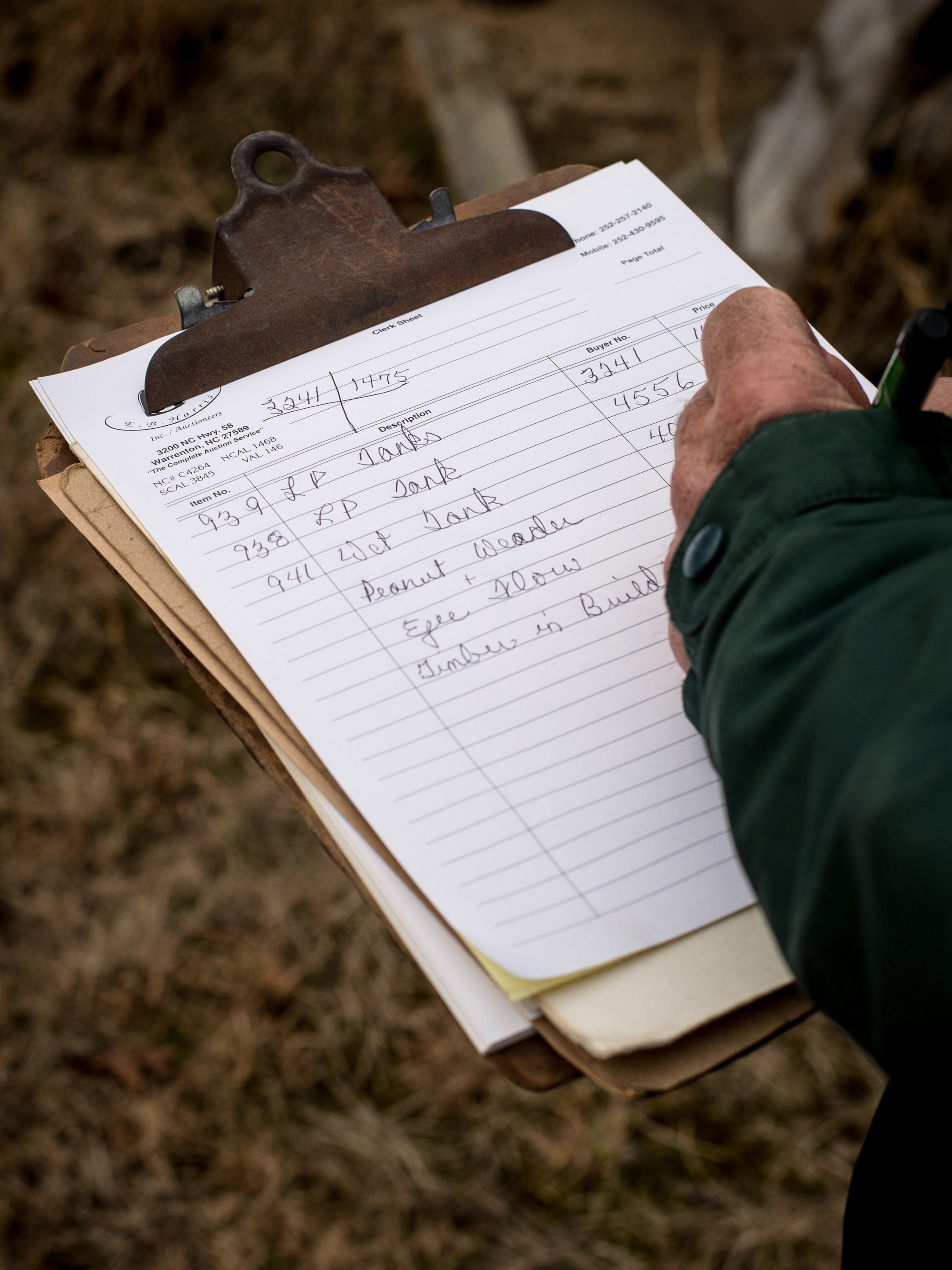

(Left) Birdman Simmons stands in front of the bus he won at the auction. An E.B. Harris employee takes notes during the auction.

Numbers tell the story. At a live auction, a turnout of 100 bidders is solid, Hines says. But if the same items are offered online, his company’s database holds more than 550,000 names. They can ship to buyers anywhere in the world. “Most of our real estate auctions we do live and online at the same time,” Hines says. “But most of the time, we are an online auction company. You’ve got to change with the technology.”

Although the chant was what captivated Detweiler and made him want to be in the business, the same is not true for current students at the Carolina Auction Academy. When Betty and Bill O’Neal founded the school in 2005, the students would have been rushing to study the art of bid calling with Eli Detweiler. The class he teaches is still required, but Betty O’Neal estimates that more than half of her students would skip it if they could. Most want to build their businesses using online platforms like HiBid and BidWrangler. “A lot of them will tell you, ‘I’m only going to do online auctions, and I don’t have to have a chant,’” she says. She begs to differ, telling them, “You never know. Technology could break.”

If he were just starting out in the business, Houston says, he would focus on web sales. It took years for tobacco auctions to disappear, and although it pains him to say so, he thinks that live auctions of cars and other manufactured goods aren’t far behind. “I’m in the fourth quarter and almost retired, so it won’t make an impact on me,” he says, “but some of the younger auctioneers, I do feel for them.” He says this is a scary time for young people in the business that has been his livelihood and passion for so long.

“There won’t be a live auction at some point in time,” he says. “That would be my prediction. And like I said, I wouldn’t put a date on it, wouldn’t try to, but I think it is headed that way for sure.”

Bobby Lee (third from left) stands with others during the auction.

On Monday night, two days after the Hepler farm sale, Detweiler is in Greensboro to sell cars at Ray’s Southern Auto Auction. In contrast to Saturday, where he had to worry about logistics, tonight he can focus on what he loves most, what brought him to the profession nearly three decades ago. Tonight he is a bid caller.

After a burger at Wendy’s, he makes his way to a large asphalt compound at the edge of town where he sells used cars two nights a week. This is a dealers-only auction, with 144 cars on the evening’s run list. It’s a different sort of crowd and a different sort of event from the weekend farm sale. Instead of oxford shirt and tie, Detweiler wears a short-sleeve plaid shirt. Most of the cars being sold need work. There are dented fenders, busted windows, and a few of them even die on the runway through the garage. These days, Detweiler and Houston sell more cars than any other item. Detweiler will be in Statesville tomorrow morning, back in Greensboro on Wednesday morning, and then back here at Ray’s on Thursday evening. He’ll be auctioning cars at every stop.

While he is the lead-off auctioneer at Ray’s on Thursdays, he closes the proceedings on Mondays. He quietly works through some tongue-twisters and sips on water under a large screen displaying the online bids. A second lane of the garage is opened and more cars roll in. One by one they stop at the front of the line and are surrounded by a gaggle of bid spotters, a sort of “Dukes of Hazzard” appraisal unit who yell out new bids like umpires calling third strikes. Detweiler climbs into the booth perched a few feet above the crowd. At 7:43 p.m., he begins to sell.

~ Watch Video ~

Tonight, he’s firmly entrenched in the proverbial zone. His voice electrifies the room. He feels the power and knows that his speed and cadence are much better than they were on Saturday, when he was sweating in a farmyard. He mounts a hill of filler words, letting them crest like a wave as he takes a single inhale, then speeds down the open face of the pause.

“32-2-2-2-All-Done?”

A streak of lightning flashes outside the garage. Online bids, piped in from the digital beyond, blink green across the monitor as he flies through another sale. Fast-fast-fast before gracefully high-stepping through “SEVEN-teen, EIGH-teen, NINE-teen,” and then sprinting again. He may not do this forever, but he’s sure as hell here tonight. A 2011 Subaru Legacy for $3,100. A Chevrolet Astro for $2,500. From 7:43 until 8:27, when he sells the night’s final car — a no-title, parts-only 2007 Mitsubishi Eclipse for $375 — everyone in the garage has experienced what is undeniably art, the transcendent flow that only the great ones achieve.

Detweiler climbs down from the booth and grabs his water bottle. The taste is magnificent. On the drive back to his farm, he will decompress. He will listen to old country music — Waylon Jennings, Loretta Lynn, George Jones. He will rehydrate, and come back down to Earth. Tomorrow he will tend the hayfields, doctor an injured calf, and sell some more cars. But until he leaves the auction tonight, he is going to feel the magic.

Jarrett Van Meter is a writer based in Asheville, North Carolina, where he also coaches high school basketball. He is currently enrolled in UGA’s Narrative Nonfiction MFA program. His first book, How Sweet It Is, is available for purchase on Amazon.

Kate Medley, a native of Mississippi, is a photojournalist and filmmaker in the American South. Her work, which explores themes at the intersection of culture and social justice, regularly appears in publications including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and NPR. She lives in Durham, North Carolina. You can find more of her work at katemedley.com.

More from The Bitter Southerner