With the arrival of Thank You Please Come Again, our new book by Kate Medley, we present its opening essay.

Essay by Kiese Laymon | Photos by Kate Medley

December 6, 2023

It started on date night and in Jr. Food Mart, my obsession with Mississippi restaurants that served gas.

This was date night in 1984.

Ofa D, my grandmama’s boyfriend, would come over Friday nights in the summer. Ofa D wore head-to-toe camouflage decades before it was in style, then out of style, then back in style to wear head-to-toe camouflage. He smelled like tobacco and, most importantly to everyone in Forest, Mississippi, Ofa D had an actual Coke machine in the front yard of his trailer. Not the goofy plastic kind, either. The kind where you had to pull out the ice-cold bottle. As quiet as it was kept, Ofa D was the sexiest man in Forest off of that fact alone. Ofa D would pick Grandmama and me up maybe 20 minutes before “The Dukes of Hazzard” came on Friday evening.

They’d sit in the front cab of a raggedy Ford listening to a Tina Turner tape. I’d sit in the back, next to burnt orange pine needles, a few broken lawnmowers, and all forms of rust. Friday nights smelled like dead chickens, piney woods, browning water, burning yard, and the insecticide that the mosquito man sprayed over every mile of Forest.

Grandmama didn’t wear her Sunday best, or even her Friday best, to Jr. Food Mart on date night with Ofa D. She’d drape herself in this baby blue velour jogging suit sent down from Mama Rose in Milwaukee. Grandmama was the best chef, cook, food conjurer, and gardener in Scott County. Hence, she hated on all food, and all food stories, that she did not make.

But Grandmama never, ever hated on the cuisine at Jr. Food Mart, our favorite restaurant that served gas.

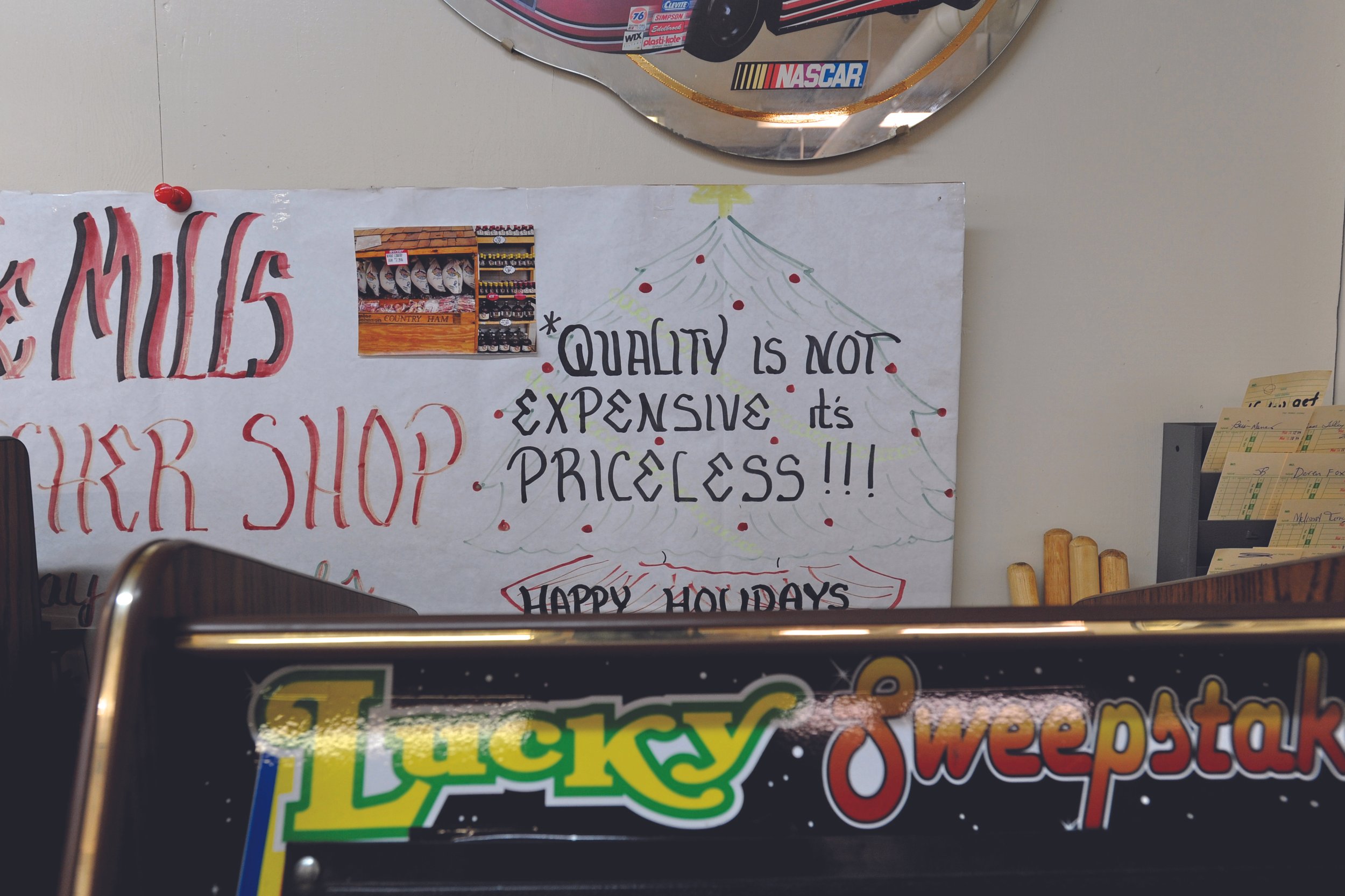

Cooper’s Country Store, Salters, South Carolina

I have no idea what I wore any of those Friday nights. I just knew that there was no more regal way to move through space in Forest, Mississippi, at 8 years old, no matter how you were dressed, than the back of a pickup truck near dusk.

At this time of evening, even on a Friday, or maybe especially on a Friday, there were more gangs of TGIF dogs roaming the roads than people walking to and from work. But I swear, even the gang of TGIF dogs were jealous of how we looked going where we were going on Friday night.

I loved everything about where we were going. I loved the smell of friedness. I loved the way the red popped in the sign. I loved how the yellow flirted with the red. I loved that the name of the restaurant started with Jr. instead of ending in Jr. Like, Food Mart Jr.

I loved that we could get batteries and gizzards. I loved that we could get biscuits and Super Glue. I loved that we could get dishwashing soap, which was also bubble bath, which was also the soap we used to wash Grandmama’s Impala, and the good hot sauce in the same aisle. I was 8 years old. I never knew, or cared, that my favorite restaurant served gas. My Grandmama and Ofa D were deep into their 50s. They seemed to never know or care that our favorite restaurant served gas, either.

I suppose there were choices of where you’d eat out in Forest. There was a Pizza Inn. There was a McDonald’s. There was Penn’s Fishhouse. There was Kentucky Fried Chicken. But there were no choices in what we’d eat on Friday. Ofa D would order a box of dark meat, a Styrofoam container of fried fish, and a brown bag filled with ’tato logs. Grandmama would grab a box of a dozen donuts. Grandmama and Ofa D would let me pick my own cold drank. I picked the six-pack Nehi Peach or RC Cola every single time.

Maybe 35 minutes later, I’d eat myself into a lightweight coma while Grandmama and Ofa D lightly petted and pecked each other on the couch with the week’s greasiest lips. This was our practice.

This was their romance.

I would have to get kicked out of college in Mississippi, then transfer to a school in Oberlin, Ohio, then go to graduate school in Bloomington, Indiana, then get a job in Poughkeepsie, New York, at 26 before I really understood that my favorite restaurant served gas, and this discovery didn’t happen at a gas station or restaurant in any of the places I went to school or worked.

I was driving back to Mississippi with my partner, a Black woman raised in the Northeast, when she commented how there were so many more McDonald’s and Subway restaurants connected to gas stations on I-81 South. “Isn’t it just so American that we will eat anything right next to literal oil and gas.”

The sentence shocked me. I’d never, ever thought about what it meant that so many restaurants on the way down to Mississippi from New York were parts of gas stations. That revelation tasted like crude oil. It didn’t taste fried at all. I remember saying, “Gotdamn. That’s so foul.”

And I’m still sure it is.

But I’d never really thought about the fact that my favorite restaurants, as a child, as a teenager, as an adult returning to Mississippi, nearly all served gas. And I never, ever thought of them as gas stations that served food. That is, until I moved back to Mississippi to teach and write in 2015.

Oxford, Mississippi, was, in many ways, as far from home as one could imagine. That’s where I came back to Mississippi to teach. But there were three restaurants that served gas between Batesville and Oxford that honestly gave my memory of Jr. Food Mart a run.

Joel Baldree, J.R.’s Aucilla River Store, Lamont, Florida

Yvonne Mires, Buckhorn Cafe, Lottie, Louisiana

This is where the story gets a bit shameful, because though my favorite restaurants serve gas, and a staple of restaurants that serve gas is fried chicken and fried fish, I haven’t eaten meat in 30 years. Granny worked the line at the chicken plant my entire childhood and I saw enough the few times I visited her at work to feel some kind of way about those little chickens, and the way the humans paid to kill, clean, slice, and wrap the chickens were paid.

Still, the restaurant that serves gas leading to the square has the best chicken-on-a-stick ever, I’ve been told. They definitely have the best fried potatoes, I know. The restaurant that serves gas on the other side of the square has the best banana pudding I’ve had anywhere other than Grandmama’s kitchen.

And the restaurant right off 1-55, at the first Batesville exit, where Highway 6 takes you to Oxford, has the best pecan pie and sweet potato pie on earth. They only sell it by the slice, though, and on my worst days — which were also my best days in Oxford — I’d drive down to Batesville, pick out two pieces of each, look over at all the fish, chicken, potato salad, macaroni and cheese, greens, and green beans and just feel so happy to be home, in a place where brutality leaves bruises, and a place that truly expects incredible restaurants to serve gas.

I missed that up North.

Yet it is the experience of eating food from restaurants that serve gas that really elucidates our American, or our deeply Southern American, conundrum. Our practices are literally poisonous. Mississippi charges me a tax for driving a hybrid car. It literally charges me for not wanting to fuck up our environment more. And. But. The friendships we make while experimenting and/or surviving the poisonous parts of Mississippi are what make our lives and definitely our childhoods — if we are willing to mine them — heavier, and actually most wonderfully Southern.

I missed that up North.

The Gizzards & Livers Store, Wilson, North Carolina

My grandmother had her 94th birthday last week. It was the first birthday we’ve had for her where the only people left (alive) were family, except for one woman who was slightly younger than Grandmama. This woman knew me and thought I should have known her. She introduced herself as Ms. Joyce. Ms. Joyce made all the food for my Grandmama’s birthday, and apparently, she was the person I’d paid to cook for Granny before she had to move in with my Auntie Sue. Ms. Joyce, I learned that day, also was a head cook at Jr. Food Mart all those decades ago.

I found a time to tell Ms. Joyce thank you for the birthday food and for the food she made at Jr. Food Mart. I asked her if she thought of Jr. Food Mart as a restaurant that served gas or a gas station that served food. Ms. Joyce said she thought of Jr. Food Mart as “my damn job.”

She said she was the cook, the custodian, the shopper, the manager, the security guard, and the server. All for minimum wage. She said the job was actually the worst job of her life in terms of pay and labor, but she never had a better time at work because she got to love on her people every Friday night. Ms. Joyce compared Friday nights at Jr. Food Mart to Saturday evenings when the bus from Jackson would arrive in Forest and all these parents and grandparents would see kids who’d moved to Jackson.

I told her I understood, and said that my favorite restaurant still serves gas. Ms. Joyce looked at me and said, “Oh, OK,” then hugged Grandmama’s neck and said, “I miss my job. But I’m shole glad not to be washing them damn dishes and fooling with them gizzards no more.”

My favorite restaurant served gas.

My favorite restaurant served gas.

My favorite restaurant paid its most important asset, a human we called Ms. Joyce, as little as one could get paid to work in any restaurant. She was paid as little as one could get paid while smelling, and sometimes pumping, gas for folks unable to pump until her shift ended at 11 p.m. This, now, is part of my favorite restaurant memory, too. And while I smell the memory as deeply as I’ve smelled anything in my life, I’m shole glad Ms. Joyce ain’t cooking, cleaning, or washing no more damn dishes in any restaurant on Earth that serves gas.

I do miss her ’tato logs, though. I can’t even lie about that. I miss our date night.

Betty Campbell, Betty’s Place, Indianola, Mississippi

Header Photo: Cooper’s Country Store Salters, South Carolina

KATE MEDLEY is a Durham, North Carolina-based visual journalist and filmmaker documenting the American South. Her work focuses on storytelling and environmental portraiture and often explores issues of social justice and the shifting politics of the region. As a kid growing up in Jackson, Mississippi, her first job was making snowballs at a gas station.

KIESE LAYMON is a Black Southern writer from Jackson, Mississippi, and the Libbie Shearn Moody Professor of English and Creative Writing at Rice University in Houston. Laymon is the author of Long Division and How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. His best-selling Heavy: An American Memoir won the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence and was named one of the 50 Best Memoirs of the Past 50 Years by The New York Times.