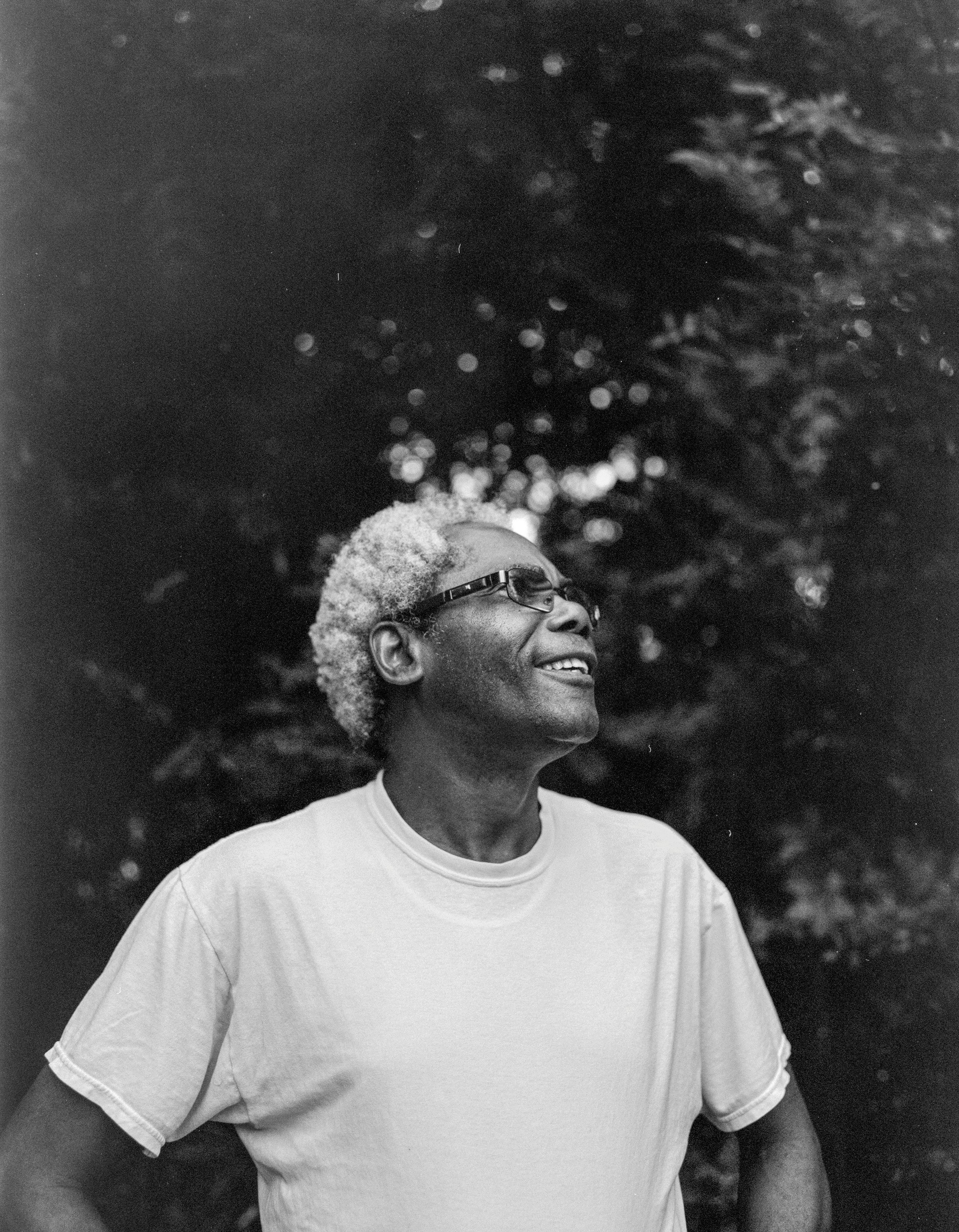

One part of the duo called the Ivory Coast’s Simon & Garfunkel, Peter One left behind his life as a popular musician in West Africa for a new one as a nurse in Nashville. He could have never imagined that he would release a new record at 67 after an American student found a cassette tape in a Ghana street market.

Words by Hannah Hayes | Photos by Ryan Hartley

September 21, 2023

On a trip to New Orleans a decade ago, I visited for the first time what would become my favorite record store. Inside Domino Sound Record Shack, a cash-only shoebox-sized shop on Bayou Road in the city’s Seventh Ward, I faced a nook of LPs sliced with Sharpie-scrawled dividers unfurling an alphabetical parade of African countries from Angola to Zimbabwe. Back then, most record stores I regularly shopped in the South had a small, afterthought “World” section — sometimes tabs for Africa’s better-known artists Fela Kuti or Ali Farka Touré. Entranced by the Technicolor covers and the promise of Saharan blues, Zambian psych rock, and Ethiopian jazz I’d never heard, I ran across six lanes of traffic to an ATM so I could bring home as many albums as I could afford.

Back in my living room, I carefully placed each disc on my dad’s old Pro-Ject One player, sat crisscross on the hardwood floor, and examined the track listings on the back covers as the records spun. I noticed the same upside-down-triangle label logo stamped in the corner on those back covers. It stood for Awesome Tapes From Africa (ATFA). One quick Google search and suddenly it was 2 a.m. I had spent hours reading the label’s blog and listening to its other artists that night on my laptop. But one album — the cover art an acoustic guitar and a piece of sheet music left behind in a rattan rocking chair — mesmerized me: Our Garden Needs Its Flowers by Jess Sah Bi and Peter One. Their high, crystalline harmonies garlanded over the warm opening strums of “Clipo Clipo” moved me much like Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” had the first time I played it while sitting on the rug of my high school bedroom a decade before.

Brian Shimkovitz, who founded ATFA, felt the same way when he happened upon the duo’s folk-country songs on a cassette tape he bought in Ghana while studying ethnomusicology — specifically, the country’s hip-hop scene — on a Fulbright scholarship in the early 2000s. Although other formats for sharing music were taking hold, the durable, pass-aroundable plastic tape deck endured in West Africa. Electrified by music he had never heard before, Shimkovitz scoured public markets for vendors with shiny spreads of DVDs, CDs, and tapes. He returned to the U.S. with suitcases full and uploaded the finds to his blog. (Spotify wouldn’t launch in the U.S. until 2011.) Keenly aware of how little money the artists had made in handshake deals with little legal copyright control, Shimkovitz turned his blog into a reissue label, releasing some of the albums from the cassette collection in partnership with the musicians so they could financially benefit from their creations.

“I quickly posted Our Garden Needs Its Flowers because I thought it was very distinctive,” he says. “Like many people, I was surprised that there was a burgeoning country Americana scene in Ivory Coast. If I could just generalize about Ivorian music, it’s extremely fast and rhythmic. So it’s interesting that their music is so laconic and so chill. Their music stuck with me for many, many years, and that’s why I just kept searching for them to try to meet them.”

Decades before Shimkovitz heard Our Garden, at the beginning of this cosmic crate-digging bridge, One himself had decided to buy a few albums for his new turntable at a local record shop in Abidjan, where he was a college student in the 1970s.

“I remember when I entered that little music store, I saw on the wall, Simon & Garfunkel,” he says. “I said, ‘This one, I want this one.’ So he brought it down and the first song he played was ‘The Boxer.’ I said, ‘Yeah, that’s what I want.’” He left with Bridge Over Troubled Water, along with records by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Bob Dylan, and Cat Stevens.

Four decades after he walked back to his dorm from that shop, One now lives in Nashville, where so much of the country music that influenced those musicians was first recorded. And at 67 years old, he recently stepped onto the Ryman Auditorium stage with one of its biggest stars.

While many in the U.S. have only seen the Ivory Coast from afar through a media lens of conflict and poverty, Abidjan (recognized as the de facto capital since the country won independence in 1960) remains a buzzing, cosmopolitan hub despite colonization’s leftover chaos.

“In Abidjan, Dakar, and the big cities in Francophone West African countries, a lot of people were traveling overseas to study or even just to go shopping,” says Shimkovitz. “So you better believe a ton of those country and Americana records got brought back. Some of the bigger ones were even distributed and sold through the normal channels.”

One, born Pierre-Evrard Tra, didn’t hear American country music until high school. As a kid in the factory town of Bonoua, One’s daily soundtrack was a mix of African music, American R&B and pop, and tunes from France emanating from a radio at the French-run pineapple processing plant. His family and nearly every other one in the rural outpost grew pineapples for the company, which One remembers as a “real cultural melting pot” of people. At home, his mother sang all the time and his stepfather made a guitar out of an automobile oil can for him, but he didn’t start strumming a real one until he was 17. When he moved to Abidjan to study, he would play at night in the kitchen he shared with his college roommates. One evening, a friend opened the door.

“He said, ‘I’ve been listening to what you’re playing. My uncle does the same music as you. I think he will have an interest in connecting with you,’” One recalls. He replied, “OK, have him come here.”

His friend’s uncle was Jess Sah Bi, and soon after they started playing together, the duo appeared on radio shows and TV spots, and put on a few shows. In July 1984, One and Sah Bi drove to a filling station and waited on a girlfriend who had promised them a pass for free gas. She never showed, but a music producer filling his tank recognized them. “He said, ‘OK, I love what you’re doing. I’m really interested. What are your plans?’ We say, ‘Yeah, we are looking for somebody to help us release a record,’” One remembers. “He said, ‘OK, I’m interested. Let’s go to my house, we’ll talk.’”

When Our Garden debuted the next year, One and Sah Bi ascended from local band to a continent-wide name — partially by One’s design to write the album’s eight tracks in three languages: French, English, and their native Gouro, the tongue of their same-named tribe. “I do that because I want my message and my music to go far,” he says. “I don’t want to just stay in a small area of the Ivory Coast. A lot of musicians in Africa just sing in their language. I want to go beyond that. So I added in French so all of Africa can hear what I’m saying. And then, I want to go further, so that’s why I added English.”

Wavering harmonicas, well-deep guitar twangs, and pedal steel runs spangle each song, but the haunting dissonance and luminosity in his and Sah Bi’s voices keep the album from sounding like a lo-fi imitation of American jukebox country. When One heard “The Boxer,” it wasn’t just the guitar tones or Paul Simon’s tenor that made it special, it was “all the atmosphere around it,” he says — the difference between a suburban patch of Knockout roses in noon light and a palm-shaded courtyard, humid and heady with jasmine and gardenias at golden hour.

One and Sah Bi played stadiums and performed for the president of the Ivory Coast. The BBC used their song “African Chant” to soundtrack the moment South African President Nelson Mandela left prison after 27 years. But it still wasn’t enough to provide the kind of financial stability either needed as the country turned tumultuous. One kept a day job as a schoolteacher and studied how to set up a production company. But the more he learned about copyright laws, the more frustrated he grew at the lack of enforcement. He attended a meeting between people in the music industry and the copyright office manager. Producers, musicians, concert promoters, and everyone adjacent flooded in with a tidal wave of questions. One saw that the overwhelmed manager had few solutions to float.

“I raised my hand and I said, ‘OK, I see that you guys are asking a lot of questions to this gentleman. He doesn’t have the answers. If we want the answers to those questions, we need to come together and think about how we are going to conduct our own thing, to have answers to those questions,’” One remembers. “That’s how they all ended up saying, ‘OK, we follow you. Do something about it.’”

With their encouragement, One took the lead on setting up the musicians union, driving around the city and its suburbs to inform and enlist people to join. Still, he had to earn the trust of this burgeoning collective.

“We knew that the more we have, the stronger we are,” says One. “Instead of going to talk on your own, if you talk for everybody in just one voice, it’s stronger.”

But the victory was short-lived as the Ivory Coast descended into violence. In 1995, One knew he was a target for his activism and chose to leave. Soon he found himself standing in New York City’s JFK airport, his expatriation relatively quick because he’d applied for a U.S. visa as a musician. Many political activists and teachers he knew who stayed behind lost their jobs; some were assassinated. Music quite possibly saved One’s life.

He walked through the airport doors to the taxi cab stand outside, and watched from the backseat window as the skyline collapsed into abandoned buildings and trash-strewn streets. This wasn’t the Manhattan from the movies that he expected. Still, people in the neighborhood helped him as he found his footing.

“I found people there who love music,” One says. “Some of them recognized me. Some just heard about me from other people. And they adopted me. They helped me in ways that I could not think of.”

From the house he shared with his sister in Los Angeles, Shimkovitz kept searching for Sah Bi and One on and off for years. Since he’d posted Our Garden to his blog, ATFA had become a respected reissue label connecting paying customers with African artists whose work would otherwise have been lost in the analog-digital divide. Starting in 2011, Shimkovitz had put out records with Malian singer Nahawa Doumbia, Ghanaian highlife artist Ata Kak, and most famously, Hailu Mergia — the Ethiopian jazz keyboardist who was driving a cab around D.C. when Shimkovitz tracked him down. Now, Mergia tours internationally and The New York Times featured his 2018 album of new material, Lala Belu, in a full-color Sunday feature. Shimkovitz wanted to give Our Garden the encore it deserved, too.

“I couldn’t really locate them in America,” says Shimkovitz. “I had a sense that they were here. I didn’t really know for sure, but I had some weird clues around on the internet.”

Shimkovitz often cold called for connections, phone numbers, anything that might lead him to a musician or producer from one of his cassettes. But even when he did get ahold of someone, he knew he was pitching an eyebrow-raising scenario.

“For the first 20 releases, I had to call people many times and really be persistent to get them to believe that I was a real person doing a real thing. In the last several years, it’s been much easier. And even occasionally people ask me to work with them. But for a long time it was like, ‘Hey, I’m some super-random guy. You don’t even know me face to face. I’m just calling you on Skype and I hope that you can trust me.’”

Finally, Shimkovitz found a woman on Facebook who had purportedly been married to Sah Bi at one point. She didn’t respond to his messages “for the longest time,” but when she did, she provided Sah Bi’s phone number. By some twist of fate, he also lived in California, up in San Francisco. When Shimkovitz then contacted One by way of Sah Bi, he had already left New York, attended nursing school in Delaware and New Jersey, and moved to Nashville in 2013. Now that Shimkovitz had their attention, he had to earn their trust.

“When he first reached out, I wanted to understand what was his goal,” says One of his first encounter with Shimkovitz. “To me, that album was already in the past, 30 years ago. But I thought, OK, if he releases that here, it’s probably going to open new doors for us. But when? And what kind of door?”

Luckily, One’s job at a nursing home gave him the flexibility to tour and a steady paycheck while Our Garden took a victory lap (although he never told his patients about his life as a musician). He had chosen his current career pragmatically to support his family but grew to love it.

“I know if I can help other people, it helps me help myself. If you’re not comfortable, you cannot create,” he says. “It’s challenging, but working here builds your personality. Makes you humble, makes you wiser. You have to change your way of seeing other people, because one day you can be where they are.”

But having a steady day job never tempered One’s tenacity to continue making music. Before he moved to Nashville, he had self-released an album he called Alesso, a Gouro word that means “doors opened.” Now that he lived in a town where you couldn’t throw a guitar pick without hitting a musician, he felt possibility — alesso.

“When I first came here, of course I had in mind that I want my music to be known here,” he says. “But I had no ideas how I’m going to make that happen. I had no plan. So to me, it was meeting the right people to release the album in a better condition.”

One attended songwriter meet-ups around town, hoping to connect with other people “who were interested in going forward, not just playing for fun.” But even when he met someone ambitious, they rarely understood One’s music or his experience. He says they’d often pigeonhole him into playing Afrobeat or reggae. He tried to record his own album twice, but the producers he worked with couldn’t see his vision. Frustrated with the time and resources he had put into two scrapped projects, One got Shimkovitz’s call just when he needed it most.

Reissuing Our Garden wasn’t easy. Shimkovitz had to navigate a legal quagmire between Spotify corporate and a distributor in Abidjan who had been collecting money from a bootleg. Once they had the rights to the music, they extracted the audio from a high-quality cassette and remastered the album in San Francisco. After they successfully rereleased Our Garden, Shimkovitz took a trip to the Ivory Coast and appeared on Abidjan’s version of “Good Morning America.”

“They were like, ‘Oh, wow, you work with those guys? Let’s have you on TV!’” Shimkovitz says. “They’re such a household name there that they gave some random dude from overseas who kind of tangentially works for them a segment on national, live TV because these guys are a big deal.”

Back in the U.S., the reissue gathered attention much more slowly. The New Yorker ran a small blurb in the “Night Life” department about One and Sah Bi’s show; a review in Pitchfork gave the album a 7.7 rating. Like Shimkovitz finding Sah Bi, I was blown away to find out One lived just a few hours away from me. I was working in Birmingham at the time when I happened upon a Nashville Scene article about him and Sah Bi performing in support of Our Garden’s rerelease in 2018.

But sure enough, as One had hoped, the right people eventually heard him. One’s manager introduced him to Memphis-born-and-based producer Matt Ross-Spang, who has worked with Margo Price, Al Green, and John Prine, among other headliners. A few others inquired, too, but One wanted to find someone who lived closer to him in the South. When he heard Ross-Spang’s other production work, he said, “Wow, yeah, that’s the young man I want to try.”

The two worked together to add in instrumentation and effects at Sam Phillips Recording, the namesake Memphis studio of the producer who discovered Elvis — a font of so much iconic American music and many of the songs One heard on the radio at the pineapple factory or bought at that little Abidjan record store. Importantly, music that couldn’t have been created without the traditions and instruments of West Africans enslaved in the South centuries ago.

Unlike other producers One had tried to work with in Nashville, Ross-Spang wanted to serve One’s vision, so much so that he made him a co-producer after he saw how One directed the band and background singers, an impressive cast including Allison Russell, Wilco’s Pat Sansone, Uncle Tupelo drummer Ken Coomer, and pedal steel pro Paul Niehaus — not lightweights by any means.

The album they created, Come Back to Me, doesn’t sound like a reprise of Our Garden (although its essence lingers, especially in the moments where Sah Bi joins his old friend). How could it? In the nearly 38 years since then, One has rebuilt his life several times over. Not a young man emulating Paul Simon’s soaring runs, he’s firmly settled into himself and secure to sing with all of wisdom’s hard-earned patina and power. “I love my voice now,” says One. “It’s firmer to me. It’s more, I would say, down to earth.” Instead of an indirect influence across an ocean, the Nashville Sound is the daily soundtrack of One’s adopted hometown, and it resonates in his songs with a realness reflective of his life’s arc.

“The musicians are from Nashville. The banjo and guitars sound like Nashville. The string pedal, it’s not the same as what we used in 1985. It’s real pedal steel,” One says elatedly.

And while Our Garden’s message felt petitionary for the future’s great unknowns, One now unearths his lyrics from a deep-rooted perspective, still written in a mix of English, French, and Gouro. The ebullient “Cherie Vico” chronicles a reunion story inspired by a cousin; “Sweet Rainbow” unfurls a chromatic admiration of a longtime layered love; and “Birds Go Die Out of Sight” eulogizes a friend killed after a homesickness-fueled return to the Ivory Coast — singer Allison Russell echoes his heartbreaking chant “Don’t go home.” In the background, chairs occasionally squeak and feet shuffle — the gravity-giving atmosphere One conjures.

A close friend of Ross-Spang’s also heard One’s music: Jason Isbell. The current king of Americana became so much of a fan, he invited One to open for him at Ryman Auditorium this past October. When he got the ask, One wasn’t aware of Isbell, so he looked him up on YouTube. “When I found out, I said, ‘Wow, I’m opening for this guy?’ I thought, I’m lucky, because I loved his music. He has great audiences. He’s a big, big star.” After a small run of shows with Isbell, One made another milestone: his debut at the Grand Ole Opry. With his halo of gray hair tucked under a black fedora, he sang for a packed house.

“When I first came to Nashville, I had no ideas of which venues to play whatsoever,” he says. “So when I had the opportunity to play in places like the Ryman, the Grand Ole Opry, it’s like the puzzle pieces of my dream are being put together.”

Since Shimkovitz started ATFA, African music, past and present, has experienced a renaissance. Today, it’s near commonplace to hear Saharan blues, Ethiopian jazz, or Zam Rock at the coffee shop or cocktail bar. But despite the revived popularity, which came hand-in-hand with streaming’s accessibility, Shimkovitz knows One’s story unfolded against all odds.

“It’s just been such a thrill to see Peter experience a whole new level of success with his songwriting on a solo level,” Shimkovitz says. “It’s great to see artists who have immigrated to the States who actually are able to swim with the fish here. The industry is extremely difficult to break into, which I know sounds like a really obvious thing to say, but the American system is completely bootstraps-oriented. His new record sounds really good.”

Like Our Garden, I found Come Back to Me in New Orleans, now the city I’m lucky to call home, but at a very different time in my life — particularly after a year that hasn’t been easy. In my living room with that same record player, I listened to the chorus of “On My Own.”

On my own

I came a long, long way

And you came along in my heart

It will take time to go through my pain

It will take time for me to love again

It’ll take time for me to trust again

One’s life couldn’t be more different from mine, but even though we don’t share the same geography or challenges or age, the hope he shares in that song was exactly what I needed to hear. That wisdom he’s earned from his unfathomable journey is a gift for everyone.

I asked One if he thought the name of his album felt like another way of saying alesso.

“A little bit, yeah” he said. “I think Come Back to Me is a way of saying that all the good things I experienced in the past, I want them to come back in a stronger way, in a better way, and keep me moving forward.”

Leave the door open. You never know who will come through or what waits on the other side.

Hannah Hayes is the former deputy editor and producer at The Bitter Southerner. Previously, she was a lead editor at Wildsam Field Guides, where she produced 10 books about American cities, regions, and road trips and, prior to that, was Travel + Culture Editor at Southern Living. She lives in New Orleans.

Ryan Hartley is an award-winning filmmaker, writer, and photographer. In his youth, he roamed the outskirts of his small town, skateboarding, making home movies, and photographing both his friends and the eccentric, yet unnoticed, locals. He now travels the American landscape, capturing the desolation of equally unique communities and the unseen people that inhabit them. He currently lives in Nashville, where he helps tell the stories of local musicians and artists.

More from The Bitter Southerner