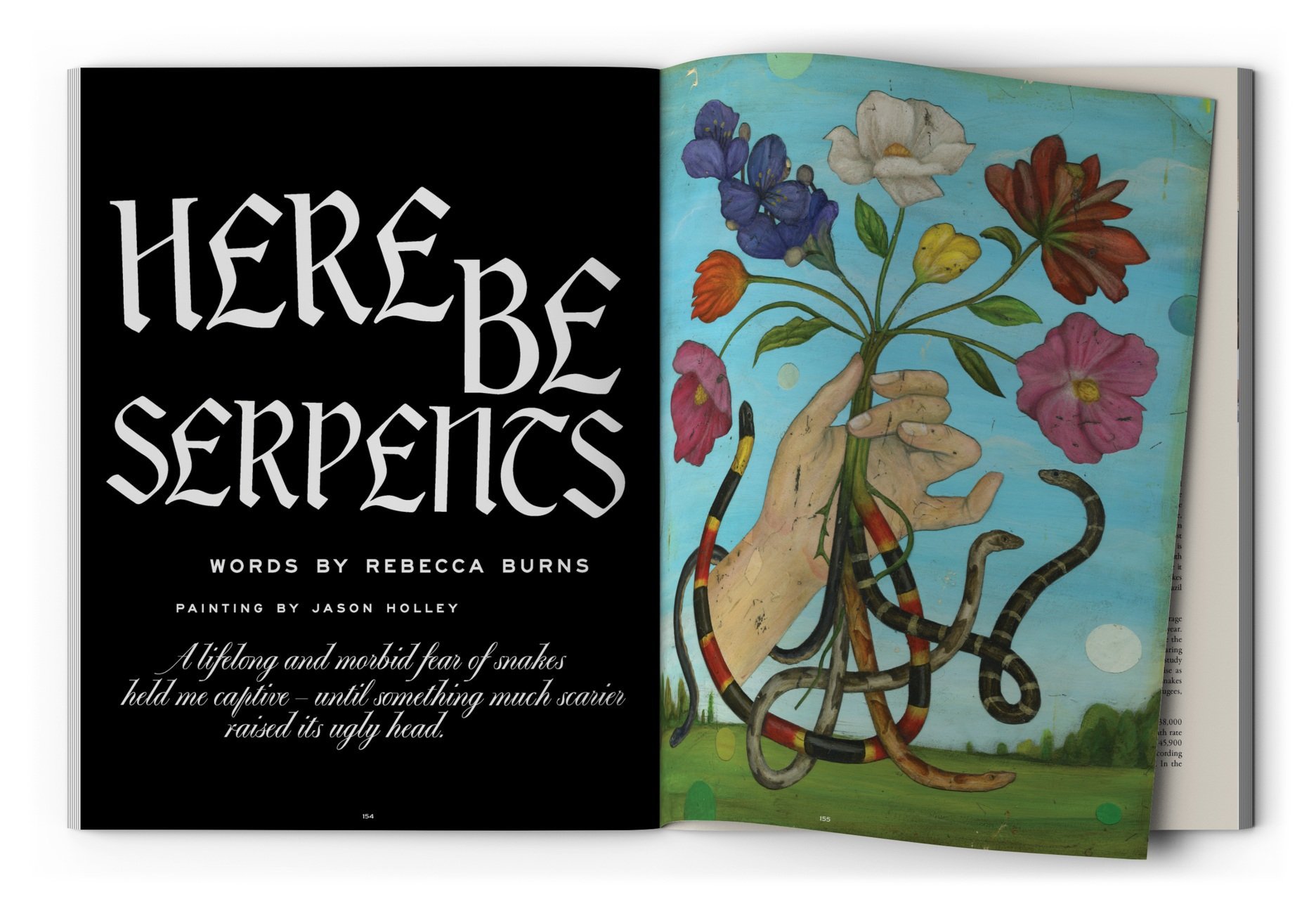

A lifelong and morbid fear of snakes held me captive — until something much scarier raised its ugly head.

Words by Rebecca Burns | Painting by Jason Holley

November 12, 2024

few months ago, as I cleaned the yard following a violent thunderstorm, my Apple Watch sent an ominous alert: Your heart rate is in the danger zone. Do you want to send a 911 call for help?

No, I did not. My pounding heart had nothing to do with the exertion of picking up fallen branches and everything to do with my hypervigilant scanning for snakes. Ignoring the watch, I reached down into the leaf mold to grab a stick. At least I hoped it was a stick — not a lurking copperhead.

A trick of the mind that transforms everyday objects into snakes is one hallmark of ophidiophobia — from the Greek ophis, snake, and phobia, fear. There’s nothing rational about my fear, but I think it’s understandable, thanks in part to spending a chunk of my childhood in India. Long story. But here are a few short stories to illustrate my point: A Russell’s viper once shed its skin in our bathtub. Our next-door neighbor, a snake charmer, kept dozens of snakes in sheds behind his house, and his 10-foot cobra once made its way to our verandah. Before that incident, we’d slept on traditional straw mats on the cool tile floors. Afterward, my mother made us sleep in beds, the mosquito netting tucked in on all sides.

Some kids take field trips to farms where they pet goats or milk cows. We trekked to a snake farm and watched workers milk venom from snakes kept writhing in pits.

I called my mom to confirm these memories, and she mentioned one I’d suppressed — or at least softened. “There was that time you were banging with sticks on this clay pile that looked like a termite hill. Then a guy came racing over telling you to stop. It was a king cobra nest.” Oh. “I remembered digging in a dirt mound filled with worms,” I told her.

When we lived in Kerala, in southern India, we were cautioned never to walk through the backyard after 3 p.m. “The snakes will be out in the grass and stay there until evening,” the housekeeper warned.

Then again, we heard similar warnings when we came back to visit family in the U.S. There were the glossy swamp snakes near our great-grandmother’s house in Lake Charles, Louisiana; the rattlesnakes in the bamboo behind our grandmother’s garage in Corpus Christi, Texas; the water moccasins in the rivers where we swam with our Arkansas cousins. We spent a summer visiting my mom’s family in Norway, where it was so cold that no fish lived in the lake, but adders sunned themselves on the rocky shoreline.

“When we start to list them all, you really did have a lot of encounters with snakes,” my mom said.

What I remember most vividly was not an actual snake, but the possibility of one. In India, eggs were delivered and stored in the same kind of straw baskets snake charmers used to schlep their cobras. Once, sent to get eggs from the pantry, I could not bring myself to open the basket. I stared for what seemed like an hour, chest clenched, skin clammy, envisioning the cobra that would rise from the basket as soon as I touched the lid, its hood flared, its tongue flickering. I returned to the kitchen empty-handed.

Five decades later, I remain terrified of walking across a moonlit lawn or even strolling along the sidewalk after dusk. Every fallen twig looks like a baby rattler. To avoid snakes, I have never tubed down the Chattahoochee or hiked through the Oconee Forest. I decline invitations to lake houses and cookouts. Forget camping.

Snakes live rent-free in my mind, not to mention — I’m certain — my home. An exterminator once told me snakes live in the walls of 90 percent of Southern homes. They wiggle behind the drywall to get from the crawl space — where they hunt mice or palmetto bugs — to the attic, where they soak up heat. “You have a long-term tenant,” a friend was told during her home inspection, which revealed an attic festooned with dried snake skins.

Avoiding snakes — by avoiding the outdoors — guided my behavior for most of my life. Then, during the dull months of the COVID lockdown, boredom finally drove me out into the yard.

Some people plan gardens with lovely pastel-shaded maps plotting annuals, perennials, and trees. I maintain a mental map — it has sunlit areas and flower beds where I feel safer, and overgrown green zones I have ceded to the snakes. “Here be dragons,” bygone cartographers wrote across unknown territories. I look at the dense ivy that borders our property on one side, the snarled privet and mimosa on the other, and the overgrown rhododendron in the back, and declare: “Here be serpents.”

Ancient mariners feared sailing off the flat edge of the earth when they ventured into uncharted, monster-infested waters. I simply need to summon the courage to stroll into some English ivy. How hard can it be?

• • •

Lots of people are scared of snakes; they rank in our collective top fears, along with spiders, public speaking, thunderstorms, vaccinations, and doctor visits. Ophidiophobia, on the other hand, is a debilitating anxiety that affects life decisions, triggers physical manifestations, and includes imagining everyday objects are snakes. A Freudian will offer an obvious serpent/phallus interpretation, while a Jungian will insist snakes represent new life phases. One of my past shrinks, a behaviorist, advocated exposure, which led to my forays into the Zoo Atlanta reptile house. These visits triggered swooning spells worthy of a Jane Austen heroine — but did not reduce my anxiety.

Snakes play an outsize role in our mythologies. The Bible’s first antagonist is, of course, that serpent who tempted Eve. The story I always found most terrifying was when Moses and his brother, Aaron, go to Pharaoh to demand freedom for the Israelites. At God’s direction, Aaron transforms his walking staff into a snake. All Pharaoh’s magicians turn their staffs into snakes. Aaron’s serpent morphs into a sort of King Snake that gobbles up all the others. Against that biblical backdrop, my mental switch that transfigures branches into boa constrictors doesn’t seem so crazy.

Across cultures, snakes are considered central to the earth itself, from the Maya Vision Serpent that coils in the World Tree to the Norse Jörmungandr, a giant sea serpent circling the realm. Kaa is the terrifying villain of The Jungle Book. Even fearless Indiana Jones is rattled by snakes. Samuel L. Jackson fought snakes on a plane. A serpent kills Le Petit Prince. Before he created Dracula, horror master Bram Stoker wrote The Snake’s Pass, a twist on the legend of St. Patrick driving serpents from Ireland.

My favorite childhood book, The Secret Garden, opens with a particularly grim variation of the orphan trope: A cholera outbreak kills everyone in heroine Mary’s India home; the only living soul left in the house with her is a green snake. Mary eventually ends up in Yorkshire and reclaims an abandoned garden. As a kid, I fantasized about doing the same, but it seemed impossible to reconcile the desire to dig in the dirt with the fear that the soil would be writhing with serpents. (I suppose I did internalize that muddy cobra nest incident accurately.) As an adult, I limited yardwork to mowing and edging — noisy tasks certain to scare off snakes. I preferred living in lofts, no gardening required.

When we moved from Atlanta to Athens, Georgia, we ended up buying a 1950s ranch house on a sloping half-acre lot. This is the closest I will get to country life, and some of the wildlife encounters have been enchanting, like the fawn twins grazing on the lawn or the neighborhood fox who patrols at night. But shortly after we moved in, we saw a 5-foot black racer wriggle across the backyard. Later, I found a scarf-sized snake skin on a downspout and another at the base of the mailbox. Chatting with my neighbor — as he stood on one side of the tangle of ivy and thorny olive shrubs between our yards and I stood on the other — he casually mentioned that he’d seen 20 snakes there in a month, before he gave up counting. “A lot of snakes drown in my pool, too,” he said. I excused myself and tried not to die.

According to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, there are 47 snake species in the Peach State, among them the yellow-bellied water snake, the southern hognose, the coachwhip, the scarlet king, the racer, the ringneck, the rainbow, and the mud snake. Seven species are venomous: the copperhead, the eastern cottonmouth, the Florida cottonmouth, the eastern coral snake, and a trio of rattlesnakes — timber, eastern diamondback, and pygmy. One of the most snake-infested places in the United States is Lake Hartwell, Georgia. The American South is home to dozens of snake species. Maybe it should be a comfort knowing Southern snakes have nothing on India (305 species) or Brazil (420). But it’s not.

The Georgia Poison Center takes an average of 500 venomous snakebite calls a year. That number is projected to surge. Like the rest of us, snakes are affected by soaring temperatures. An Emory University study showed that in Georgia, snakebites rise as temperatures do. Across the world, snakes have become climate change refugees, migrating as their habitats overheat.

Globally, snakebites kill up to 138,000 people a year — with the highest death rate in India, which records an average of 45,900 deadly “envenomations” annually, according to the World Health Organization. In the United States, according to the CDC, only five snakebite deaths occur annually.

• • •

If you have an irrational fear, statistics aren’t very calming. So back in 2020, when I decided to actually venture into the yard, I enlisted my husband, Jim, for moral support and to stand guard.

“I’m going into Snake Land and I need you to come watch,” I would say.

As I raked leaves and debris, I ordered him to stand a few yards away, a shovel in one hand and a mobile phone in the other, ready to either clobber a snake or call 911.

“Do you think the EMTs routinely stock antivenom?” I wondered.

“You’re not going to die of a snakebite,” Jim said. “You’re going to die from heat stroke out here.”

“No, I am pretty certain it will be a snakebite,” I insisted.

The immediate danger, it turned out, was not serpents but smilax. With a name out of Dr. Seuss and behavior out of the Brothers Grimm, smilax is a nasty briar that had spiraled through all the plants on our property, evidently never controlled since our house was built in 1958. As I yanked vines that twisted 30 feet into the trees, thorns scratched my arms and shredded my work gloves. I wondered: If orphan Mary had been shipped off to live with relatives in Georgia instead of Yorkshire, would she have been as interested in uncovering a secret garden hidden by smilax? A year into the yard project, I learned that smilax — the type at my house is also known as deer thorn or catbrier — grows from rhizomes that spread below ground, squeezing between the roots of other plants. Simply cutting off the vines at ground level was not enough. I had to excavate.

“These are like Harry Potter’s herbology homework,” I told Jim as I dug up hideous lumps, some the weight and size of bowling balls.

Despite a total lack of interest in yardwork, Jim patiently stood watch and made congratulatory sounds when I insisted he come over to inspect a particularly gruesome specimen.

Quarrying the smilax meant getting really close to the ground. “I’m pretty sure I’ll dig into a snake pit,” I fretted.

Eventually, we learned the only tool to break through Georgia clay and loosen smilax rhizomes was a mattock, or pickax — heavy-bladed and long-handled. Thus armed, I felt braver.

“Just come out while I rake things out of the way and get started,” I told Jim. “You don’t have to stay after that.”

I found no serpents among the smilax roots, but I did once wake up a little DeKay’s snake napping under the mulch. I surprised a bigger brown snake under a stack of pruned tree limbs. I did not vomit or panic or faint. I felt pretty proud of myself.

When I got a little more comfortable, I became obsessed with dahlias, cursed the adorable eastern cottontail who ate my perennials, started a pollinator garden, distributed a literal ton of mulch, and assembled compost bins.

Smugly, I watched — from the safety of my home office window — as a 6-foot rat snake writhed through the flower beds. I spotted him a few times, gave him an unoriginal nickname, The Snake, and felt sure I’d made progress.

Then one day, I went into the backyard shed to put away some flowerpots and found The Snake stretched out luxuriously across the floor. He stared at me. I fled to the house.

“Are you having some kind of panic attack?” Jim wondered, as I slumped to the floor, back against the wall, panting.

“Yes. The Snake has taken over the shed. You need to go shut the door,” I finally managed to gasp. “Or maybe it’s time to demolish that shed.”

To his credit, Jim did not laugh at me. Eventually he went and closed the shed door. Eventually I caught my breath. I have not been back inside the shed since.

• • •

Away from the smilax and shrubbery, I mounted a self-education campaign. I joined the “Snakes of Athens” group on nextdoor.com and forced myself to look at the photos posted by my neighbors: copperheads in carports, rat snakes climbing rain gutters, mystery serpents in kids’ sandboxes or coiled in planters. Most people simply post a snapshot and ask, “Is this a good snake or is it poisonous?” Herpetology enthusiasts point out “all snakes are good” because they supply natural pest control and haughtily note the correct term is venomous, not poisonous. There’s always one person who insists the only solution is a gun. I study PSAs from the Department of Natural Resources that, like those old Magic Eye puzzles, challenge you to spot snakes camouflaged against tree bark and leaf piles.

These days, when we encounter a dead snake on our walks (once we’re sure it’s truly dead), I practice my snake ID skills.

“They say you can tell a copperhead because it has markings that look like Hershey’s Kisses,” I tell Jim. “That’s a whole new twist on ‘death by chocolate.’”

“I was told that copperheads smell like cucumbers,” he says. “But honestly, I don’t think I can tell you what that smells like.”

Still, when I’m out in the yard, I find myself sniffing for cucumbers.

One section of my Snake Land is also home to a glorious old gardenia, 7 feet tall, laden with blooms each spring and fall. It’s a cultivar you can’t find in Lowe’s. It’s also entangled with smilax. Two years ago, with Jim standing guard, I removed a barrow of rhizomes from in front of the gardenia. There’s another section, behind the gardenia, densely overgrown, that I’ve been too scared to approach.

• • •

As I progressed in conquering my ophidiophobia, I faced a new fear.

Last winter, Jim was diagnosed with Stage IV prostate cancer. This spring, we stayed in Atlanta, where he underwent six weeks of daily radiation treatment. When we returned to Athens, our yard was a riot of flowers. But once again, smilax vines coiled up the gardenia.

As Jim recovered from radiation and dealt with the side effects of multiple medications, it was wrong to ask him to stand guard. Heading out to the yard alone, stretching as far as I could, I swung the mattock and hacked away. But I knew it wasn’t enough. To really make progress, I’d have to venture into the scary area behind the gardenia.

If you don’t remove all of a smilax rhizome, fragments left in the soil will take root and send up new shoots. We don’t know if the radiation has destroyed all of Jim’s cancer cells. We don’t know if the meds still stave off new cancer from growing. For months, I stayed preoccupied by attending medical appointments, parsing the verbiage on lab reports, offering moral support, doing chores. I kept myself too busy to give into grief or acknowledge my fears. But on this day, as I tugged on vines, tears streamed down my face along with the sweat.

You can see a snake. You can identify its markings. Cancer cells are invisible. I was so overcome by this other fear, this rational one, that for a while, I forgot about the snakes.

Snakebites kill only five Americans a year. A projected 611,000 Americans will die of cancer in 2024.

• • •

It’s time for professional help.

To conquer my phobia, I decide to venture into Snake Land with the help of a guide. I schedule an appointment with Ian Bachli, an Athens herpetologist. He makes house calls that include surveying your property for snakes — and relocating any that are found. For an extra fee, he’ll examine the attic or crawl space. I book him for all three services.

He arrives wearing jeans, Crocs, and a baseball cap, carrying a long metal hook in one hand and a pair of snake tongs in the other. As we walk through the yard, Bachli prods at plants and swirls the pine mulch, while I describe past snake sightings.

“Snakes want to hang out where it is warm in winter and cool in summer,” he explains, lifting up lantana in the front flower bed. “They need to regulate their temperature.”

We make our way up the sloped backyard and to the shed. It is fully my intention to venture inside, but I just can’t do it. Bachli pushes open the door, shining a flashlight into the dim interior and holding the hook in front of him. I am not sure if this is to reassure me he’s taking me seriously or because he thinks there might actually be snakes in there. I stand paralyzed a few yards from the shed and listen to him tap around inside.

“There are no signs of snakes,” he cheerfully reports. “No snake skins, and no mouse droppings, meaning there’s no food to tempt them.” He tells me there are a lot of holes in the flooring where snakes could easily get in, and suggests repairing them. “You don’t want 20 snakes moving in here,” he says. Absolutely not.

Bachli says the mistake gardeners make is getting low and starting to work without checking. Tap around with a rake or shovel before you reach down to pull weeds or prune plants, he advises. “Snakes won’t attack you, even if you startle them, if you do it from a distance. You are so much bigger. They think you want to eat them.”

We reach the gardenia and I ask him how to approach the overgrown area behind it. He suggests wearing tall work boots. While there are fancy boots made with materials like Kevlar, you just need sturdy rubber ones. “Even if copperheads strike the boots, they can’t bite through the rubber,” he says. “Their fangs are short.”

We go to the crawl space. A while back — if I think about it, around the time The Snake moved into the shed — we had mice. Exterminators replaced the crawl space door and sealed openings. “They did a good job,” Bachli says. “If snakes were getting back in here, you’d see shed skins near the doorway.” No signs of mice, either.

In the attic, he reaches out with his snake hook, and a mousetrap left behind by the exterminators snaps. There are no signs of (living) mice or snakes.

Snakes will never be driven away, but if you know where they are likely to hang out, you can be prepared, Bachli tells me. “You need to reclaim your yard.”

• • •

In search of work boots, Jim and I head to the farm supply shop. While I try on boots, he wanders off to see if there are any baby chicks in the incubator in the middle of the store.

I buy heavy-soled navy-and-red muck boots with reinforced toes. They reach to my knees and are about twice as thick as the cute ankle-high Smith & Hawken “garden boots” I’ve been using.

A few days later, it’s time to brave the overgrowth near the gardenia.

“Do you need me to come with you?” Jim asks.

“No. I need to do this alone,” I say.

Outfitted in the boots, heavy jeans, a long-sleeved tee, and work gloves, I make my way to the gardenia bed. With a 5-foot-long pitchfork, I poke around the ivy in my best imitation of Bachli. No snake movements. One step, two steps, three steps, I make it behind the gardenia, where I have never ventured before. The ivy is ankle height. With swings of the mattock I begin to hack away at briars and dig up roots, not even flinching when the vines wriggle as they fall to the ground. ◊