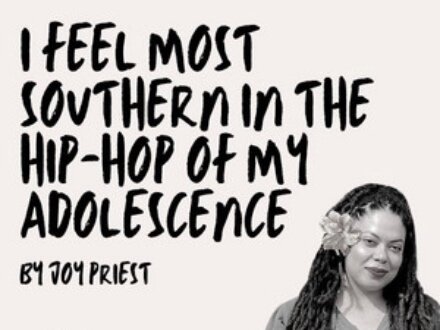

Each writer in the new book A Measure of Belonging: Twenty-One Writers of Color on the New American South (Hub City Press, edited by Cinelle Barnes) dances with the question: “Who is welcome?” In this excerpt, Joy Priest creates a Southern rap soundtrack of the cars, songs, and forces that sculpted her sense of freedom and confinement coming of age in Louisville, Kentucky, in the early 2000s.

My Southernness was seeded by the matriarchs on my father’s side, Black women who came up from Alabama sharecropping fields in the twentieth century to do “day work” — the language a euphemism for taking care of white families, a pentimento of the plantation schedule. In my own lifetime, I found affirmation of my Southern identity in the music of my adolescence, where I spent a lot of time in cars. In the aughts, Kentucky didn’t have a definitive sound on mainstream radio, but Black Kentuckians heard our experiences in Southern hip-hop no matter which state it came out of — Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Virginia. We didn’t feel Southern because we were listening to Southern rap. We felt Southern rap because the tempo matched the cadence of our lives and kept a record of the peripheral cultures that shaped our language and movement.

“Back that A** Up,” Juvenile feat. Mannie Fresh & Lil’ Wayne | “I Need a Hot Girl,” Hot Boys

New Orleans

The seminal, intra-regional anthem for the Black South came down at the end of the twentieth century. There wasn’t a party “Back That A** Up” failed to play at up through my exit from high school in 2007. A hood cult classic like Mr. Bigg’s “Trial Time.” To know every single word, affect, ad-lib was a mark of belonging.

It was at a grown folks’ house party. It was at a school dance. A family reunion, barbecue. It was at the car wash, corner store. Sundays at Cox Park. From a car radio, sound distorted as it passed from right ear to left, or a chance snippet at the stoplight. On Broadway after school, where the old skools swerved like one slow-moving, shimmering river, mimicking the Ohio running parallel nine blocks away. It was on 106 & Park, BET Uncut, Video Countdown, Cita’s World, Hits from the Streets, Rap City. It was practicing in front of the mirror. It was when we still called it “poppin.” In pantsuits, capris, sundresses, air-brushed t-shirts or spaghetti straps, basketball & booty shorts. Hair store flip-flops or fresh, white Forces. Gold nameplates and jumbo hoop earrings airborne in the slow-motion music of our millennial turn.

It was at the F.Y.E. music store on Dixie Hwy in Louisville — our city twinned with New Orleans by the fleur-de-lis. It was in a bin that held piles of compact discs, a medium so delicate and ephemeral we kept cotton pads and light-abrasive polishing solutions in the medicine cabinet. In one bin, the CD covers featured the late-nineties Ca$h Money Records D.I.Y. graphics: diamond-encrusted block letters, old skools, and cash raining down to douse flames circling Lil Wayne or Juvenile or B.G. or Turk. The flames were always the most prominent feature. The rapper was depicted in the underworld — it was easy to internalize the evil and immorality projected onto us by residents from the ‘good’ side of town — in the ghetto as purgatory, necessarily a wellspring of creativity. We invented strategies to get by, made a way out of no way. The alchemical rapper demonstrated his three-pronged strategy for keeping the heat under control — money, mobility, ice.

It wasn’t just the cover designs that held fire, but the titles too: The Block is Hot, 400 Degreez. “I need a hot girl,” sang The Hot Boys. The heat was everywhere in the Black enclaves of the lower United States: kitchen fires and hood summers; blocks saturated with police; a specific kind of girl who usually didn’t get the gift of serenade. So, when Mannie Fresh sung his ode to hoodrats, we celebrated this newfound exclusivity by blessing someone who shared our claustrophobic swelter with a dance.

Stankonia, Outkast | “Danger,” Mystikal prod. by Neptunes

Atlanta, New Orleans, Virginia Beach

In Old Louisville — a well-preserved historic district downtown, populated exclusively by Victorian houses — Ninth Street branches off from Seventh Street like an empty aqueduct. From there it begins its journey northwest toward the West End (Somebody said: “the West End the Best End!”). By the time Ninth Street makes it to Broadway — the city’s major downtown thoroughfare — it has become a border with enough narrative resonance in our city to have earned a nickname: The Berlin Wall. Called such because it separates the West End economically, politically, visually, and psychically, the Ninth Street Divide is a common phrase uttered to tourists by downtown bartenders as a boundary not to venture beyond.

Historically, it served as a divide between urban renewal “projects” and the business district. Currently, it corrals Black Louisvillians within thirty or so blocks, effectively cut off from the rest of the city, its sit-down restaurants and hospitals, movie theaters and stores. Thirty percent of West End residents do not own a vehicle. But the bus route will eventually get you to work on the other side of town, and on foot you can get to church or the liquor store, depending on what kind of spirit you are trying to catch — fire in your belly or fire on your head.

In the first year of the new century, your slightly older, teenage uncle has a 1983 Z28 Camaro, T-top. It’s a bucket, but you want the same car when you get older. There’s a detaching face CD player and some rattle in the trunk, but the power windows won’t come down, and it’s burning up in the early morning heat wave. At every pothole or railroad track, the radio cuts out. There’s a short in the wiring, but his guy says it’s not worth the cost to fix it, so he resorts to the usual: banging on the dashboard until it cuts back in.

2001. “Raise Up,” Petey Pablo, produced by Timbaland |

2002. Watermelon, Chicken & Gritz, Nappy Roots | Choppa Style, Choppa

Greenville, Norfolk, Bowling Green, New Orleans

At the end of every week, we started in early with pleas to convince our parents to let us go to Saturday Skate at Champs roller rink, located on the ominously curvy Manslick Road, where the working-class white and Black sides of town converged. It was, each time, a difficult convincing, considering the night always ended prematurely with a fistfight or a skate opening someone’s scalp. But somehow, we managed to arrive under the glow-in-the-dark purple lights with money-in-hand for speed skates and Surge soda.

There was always a favorite cut that got everyone to the floor, when the rink reached capacity and speed skates became pointless inside the slow-turning mass. Petey Pablo was talking about a place none of us had thought about before, but when “rep yo city!” refrained from the rink speakers — in that gravel-crunch voice that held the church and the liquor store — we raised up.

Maybe North Carolina hated this song. Maybe the “big city” Black folks in Charlotte were embarrassed by that country shit, the way “big city” Black folks in Louisville were embarrassed by the first, mainstream Kentucky rap group that would debut the next year with Watermelon, Chicken & Gritz — a corny misrepresentation too public to defend. When they sang about their newfound contentment with lifelong poverty, in an over-pronounced twang, we weren’t trying to hear that. Being poor definitely still mattered to us and the struggle wasn’t something we were in a place to look back on, as teenagers, and celebrate. Still, these songs of representation at the beginning of the millennium portended a come up for those of us living in American obscurity.

As we transitioned into the Crunk era, reppin' your city became reppin' your set. Our spaces shrunk and our divides multiplied beyond North-South or poor Black-poor white. The block got hotter and our square radius became even more constricted.

In the meantime, back at the rink, we kissed our teeth at the boys and skated onto the floor to the “ooawwwww” and wop wop drums that signaled the start of “Choppa Style.” In that moment, wasn’t none of us trying to parse our circumstances with intellect. We were trying to feel it. Trying to turn so many revolutions around that rink that we couldn’t feel the heat anymore for the wind. We knew what difference a breeze made inside a cage, how much mobility mattered inside a loop you couldn’t figure out how to exit.

“Never Scared,” Bone Crusher | “24s,” T. I. | “Like a Pimp,” David Banner | “Ridin’ Spinners,” Three 6 Mafia | Gangsta Musik, Boosie & Webbie

Atlanta, Baton Rouge, Jackson, Memphis, New Orleans

After roller skates, but before rims, there were the wheels on the bus. School bus. City bus. For a few hours a day, passing between the enclosure of our neighborhood and the enclosure of a school building, you got to be rogue and alone. Or, at least you didn’t have to talk to nobody. Inside the private experience of the Walkman, the CD revolved silently. Some songs you spun so much the CD began to skip…swer-swer-swer-swer-swerve on ‘em. Or, after a while, the wire to the headphones would short, at which point you’d have to find the spot in the wire and pinch it just right for the duration of the ride lest your music sound distorted and distant, like someone had thrown a low pass filter on it. Once the wire shorted, you had to find someone to let you hold $10, and then you had to walk down to that Walgreens to get new earphones. The Walgreens past your ex-best friend’s house, where, after he had bought you a large McDonald’s fry, her older brother lured you to his room under the guise of music and tried to get you to let him lick you between your legs. You could man up and go down to Walgreens, vulnerable on foot or, the next day, you could ride in the 6 a.m. silence with the whole, deadening school day ready to come down on you.

Nuthin But Fire Records, New Orleans, Louisiana

Crime Mob, Crime Mob | Tha Carter, Lil Wayne | Urban Legend, T.I. | Straight Outta Cashville, Young Buck

Atlanta, Nashville, New Orleans

Some of us left in the furnaces of steamboats. Some left as porters on the train. Some stayed. Some migrated North, but not far enough. If you landed in Kentucky, say, from Alabama, you might have thought of it as the North before you got there, but realized it was still Dixie once you arrived. Everywhere in America, Dixie. Everywhere a running history of bondage beneath the surface of society, peeking out.

In the nineteenth century, rather than a plantation structure, the Louisville economy was organized around a bondsman system — an ironic mobility for Black folks who were “rented out” to various proprietors around the city for task-based jobs, rather than confined to an estate, physically-speaking. In the mid-twentieth century, this class structure remained in place, but mobility became increasingly more restricted after 24/7 electric streetcar service ended in 1948. As Black folks bought homes, white flight commenced in the West End, and the Ninth Street Divide became a defining reality.

To have your own car meant everything. It was a symbol of mobility and success in a Southern city that did not have a mass public transportation system or an Amtrak rail to ride out of state — just a fraught inner-city bus line to get you downtown to your restaurant job or assembly line. Fast-forward to the aughts and car culture was a thriving, Black Southern art genre, a canvas for one’s personality and style. This was one of the peripheral cultures that Southern rap preserved for us, alongside our dance anthems and idioms, gold grill fronts, lunch table beats and internalized misogynoir.

The fall of her sophomore year, a girl drives her 1988 Cutlass Supreme Classic to school with just a permit (a perfectly acceptable thing to do as a 15-year-old in Kentucky). Her father’s co-worker at Hytec Cutting Services has sold it to her for a charitable $500.

When she drives up to Central High Magnet Career Academy — a fancy name that belies the poor state of Muhammad Ali’s historically-Black alma mater — she has the respect of men. They begin to invite her on exclusive dips to practice formations for “cruising” at the park or on Derby. In the era of Crime Mob, when even the dudes rap Princess’ and Diamond’s verses, it is acceptable to have a girl in your crew. And, as a girl, if you have something that interests boys besides your body, it saves you a lot of trouble.

The body of her car is in mint condition. Oxblood drip. 307 V8. At post-9/11 gas prices, her entire Sonic Drive-In paycheck starts going to gas. It doesn’t matter, as long as she can take herself wherever she wants to go and leave whenever she wants to leave, as long as she isn’t the girl Young Buck raps about in “Shorty Wanna Ride,” trapped in some dude’s fantasy, just another commodity, or feature of his car.

Thug Motivation 101, Young Jeezy Savage Life, Webbie | Who is Mike Jones? Mike Jones | The People’s Champ, Paul Wall | Tha Carter II Lil Wayne | The Sound of Revenge, Chamillionaire

Atlanta, Baton Rouge, Houston, New Orleans

2005 was the definitive year. We stayed with a burnt copy of Thug Motivation 101 on repeat and by now some of us had managed to get two 12s in the trunk with whatever was left over from our busboy tips and dime bag sales after helping out at home. It was the year Mike Jones gave out his number on record, the year we rapped along to “Flossin” at the top of our lungs out the window. It was the year Chamillionaire gave us an anthem for racial profiling, and Webbie spit every car known to man in a 16. It was the year even a white boy came with that heat on “Sittin Sidewayz,” “Still Tippin,” and “Drive Slow,” and had the internet going nuts before most of us even had the internet.

“Let’s meet up on 11th street tonight,” Man-Man yells out his window at the Marathon gas station before we get tight out of the parking lot and down 18th street: our after-school tradition. The heat built up over the course of a day inside our air condition-less school building.

Sometimes we’d drive in a formation. We had the choreography down because we rode together a lot, went on dips out on the empty, old roads. We knew one another’s cars down to the transmission, and how a certain person drove, their idiosyncrasies and inclinations toward stupidity and recklessness. We were made lion-hearted by our mobility.

We were also made more vulnerable. Having a car meant more encounters with the police.

That year a girl gets her first reckless driving charge for burning rubber as she turns from 18th onto Broadway, and, just in case her high yellow ass is still confused about how white people and authority figures see her after 12 years in public school institutions, the officer makes sure to check “Black female” on the citation.

King, T.I. | Port of Miami, Rick Ross | Thug Motivation 102: The Inspiration, Young Jeezy Dedication 2, Lil Wayne | Underground Kingz, UGK | “Throw Some Ds,” Rich Boy | “Shoulder Lean,” Young Dro

Atlanta, East Texas, New Orleans, Miami, Mobile

By 2006, we were in an era of sequels. The murder count in our city rose, and loss became so mundane as to be anti-climactic, sublimating our joy and suspicions of an elsewhere. Some encounters lasted longer than others. Sometimes we were each pulled out of our cars and questioned individually. Sometimes we asserted our rights — “no you may not search my car” — but most of the time we had none. Sometimes they made us leave our means of transport behind. Sometimes we chose to leave it, voluntarily, while the whip was still in motion. A ritual for our ghosts to ride.

One day a girl walks out of the school building to find her parking spot empty. Weeks later, her Cutty is found in Victory Park, a Crip-heavy block in Louisville’s California neighborhood. Unwilling to walk in and retrieve it, she has to wait for it to be towed.

A month later, on her way home from the impound lot, the rods are knocking and the motor running hot, turning off at every light she comes to. Some young kids on a joy ride dogged it. Eventually, it locks up, right where 18th turns into Dixie Hwy — the engine gone quiet, the music persisting into the warm night. She sends word to one of her boys to come get her and he comes.

Rapsody | Missy Elliott | Megan Thee Stallion | Janelle Monae | Diamond & Princess | City Girls | Trina | Left Eye | Lizzo | Big Freedia | CHIKA | Mulatto | Jacki O Khia | La Chat | Gangsta Boo | Chyna Whyte | Mia X

Some fifteen years later, I look back on the soundtrack of my teenage angst and realize that women rappers — while tucked into a verse here and there in our CD cases and LimeWire files — were not as prolific or celebrated in the rap we gloried in as the men. I was trying to survive my girlhood, not make it conspicuous via loud recitation.

If this was the record of our lives and, if the voices of women rappers were non-existent or accessory, then so were ours, so were we. What this archive reveals is that, when we were young, what started as a weak solidarity between boys and girls advanced to a game of chase, the psychology of the hunt, and graduated to expectations of sexual favors and harassment as a measure of one’s manhood. In this progression, all association with femininity became dangerous; to distance yourself from the feminine in you was a survival strategy.

However, Southern women make legible a whole periphery of possibilities. What kind of mobility would they have offered to a 16-year-old Black girl wanting out of a male-oriented cypher? What vehicle? Self-possession: “I remember when hot girls and hot boys needed one another,” read a recent tweet in response to Megan Thee Stallion’s 2019 Hot Girl Summer campaign. The tweet was a clever reference to the 504 Boyz hit twenty years earlier. A lament, but a necessary one. Hot girls and hot boys definitely need one another, but this togetherness requires a revisioning: a solidarity in which we recognize and honor the full humanity of one another, and ourselves. If we continue to look at women/femmes as potentially exploitable, we are only mobilizing toward more airless purgatories.

Mental mobility: Last year, Rapsody put out a 16-track album — each track eponymously citing a Black woman, a small liberation of the archive. And, a few years before, on Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 To Pimp a Butterfly, she dropped her anti-white supremacist ethos. For her language and thought are the currents on which we take flight.

Joy Priest grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, on the backside of the world’s most famous horseracing track. She is the author of Horsepower, winner of the 2019 Donald Hall Prize for Poetry from AWP, and a 2019-2020 Poetry Fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. Her poems and essays have appeared in numerous publications, including Callaloo, Connotation Press, Four Way Review, espnW, Gulf Coast, Mississippi Review, The Rumpus, and Third Coast.

Landon Antonetti is a photographer from Louisville, Kentucky whose photography focuses on the unique cultures that make up not only Central Kentucky but the surrounding southern states.