Eighteen years ago, John Edwin Mason, who teaches African history and the history of Photography at the University of Virginia began making photographs at Eastside Speedway, a minor-league drag racing outpost in Waynesboro, Virginia. There, to his surprise, he found a multiracial community of racers, fans, and track personnel, united by their love of racing, with tight, interracial friendships going back decades. Eastside is closed now due to COVID-19, but Mason believes the track’s community will hold together because, despite its flaws, he argues, it has “come closer to fulfilling the promise of equality than the country as a whole.”

Essay & Photographs by John Edwin Mason

All Photos Copyright John Edwin Mason, 2002-2012

It's a strange thing to be writing about these photos during a pandemic and what amounts to a nationwide police riot. I began this project in 2002 and was done with most of the shooting by 2010. That's long enough ago that both the time I spent at Eastside Speedway, just outside of Waynesboro, Virginia, and the images themselves have taken on the rosy glow of nostalgia. I remember the days and nights that I spent making these pictures as some of the happiest times in my life. I can't say that's wrong. But the truth is I started going to the track because I was lonely. The people in these photos became friends when friendship was what I desperately wanted. Collectively, they formed a community when a sense of belonging is what I needed. I'll always be grateful for that.

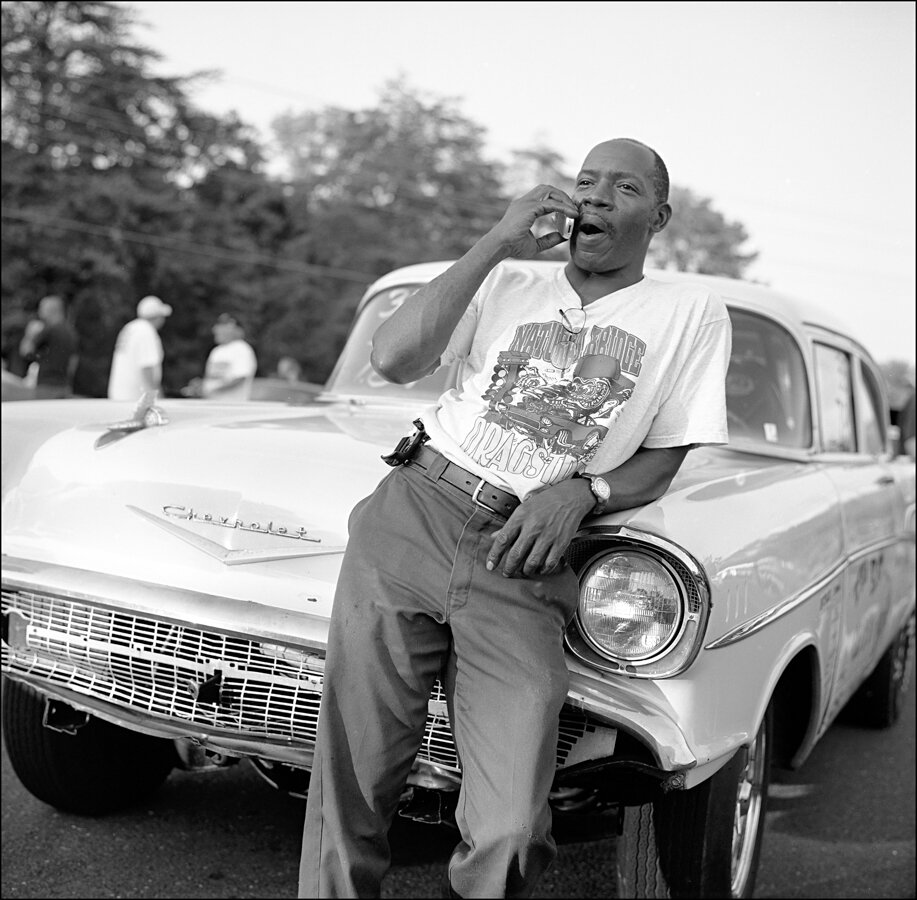

When I drove out to Eastside for the first time, I didn't know I'd make friends and become part of a surprisingly diverse racing community. I was just thinking it would be fun to spend an evening making photos of fast cars and smoky burnouts. I'd seen an article in a local newspaper that made me suspect that I could get close to the action. On the way out, I felt a touch of trepidation. I'd been into racing all my life, but I'd never been to a dragstrip. I wasn't sure exactly what to expect, but overt hostility didn't seem to be out of the question. Waynesboro is a small Southern city that's struggling economically. Drag racing is a macho, working-class sport. And I'm black. That added up to me being apprehensive.

But I've never been much good at math. The first thing I noticed after I parked the car and walked toward the pits, is that I wasn't the only African American there. Far from it. Many of the racers were black. So were plenty of the spectators and one or two of the track's personnel. Most of the people at the track, from racers to workers, were white, and many of them had friendly relationships with the black people who were there. (I was to learn that these friendships often went back decades.) None of this made much sense to me. In all my years of reading automobile magazines, watching races on TV, and occasionally going to a track in person, I'd never heard of more than a handful of black racers, none of whom were drag racers. I had a lot to learn.

It turns out that no motorsport has been more open to African Americans and to other people of color than drag racing. What I saw on my first trip to the track is duplicated all over the country, from small, grassroots dragstrips, like Eastside, to the large corporate tracks that attract the National Hot Rod Association's top professional racers. The same is true for women racers, and it's been this way for a long time.

African Americans started racing at Eastside when it opened in 1965 — that is, when the "Whites Only" signs were only beginning to come down throughout the South. Women were racing there by the 1970s. Elsewhere, African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans had been a part of the drag racing scene since its beginnings as a formal sport in the late 1940s. Women also have an extensive history in the sport, one that starts in the 1950s and includes world champions like the late Carolyn "Bunny" Burkett, who appears in several of these photos.

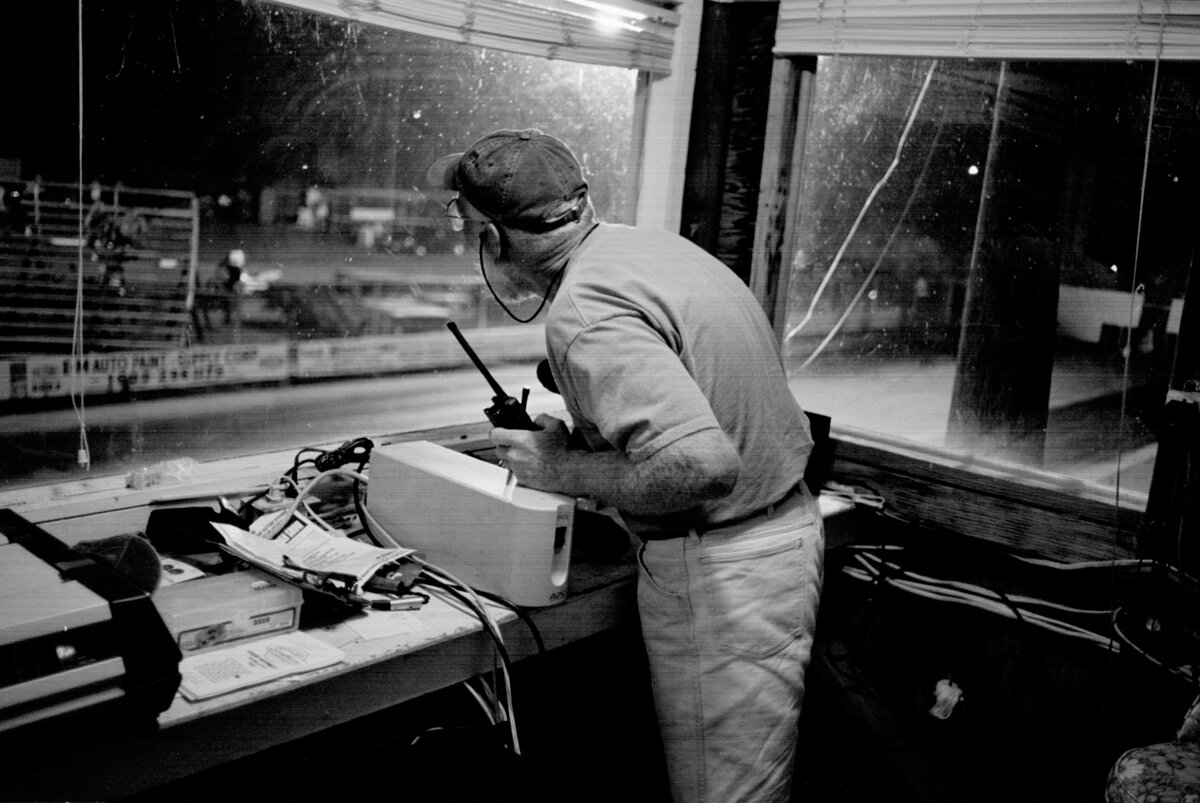

Eastside is silent now. The racing season had barely begun when the coronavirus pandemic shut it down. Gary Gore, whose family has owned the track since it opened in 1965, doesn't know when he'll be able to reopen. One driver I got to know the best — let's call him Larry — caught the coronavirus and spent several weeks in the hospital. He's recovered well enough to return to work but doesn't know if he's ready for the physical and psychological demands of racing. And Bunny Burkett, a genuine icon within the East Coast racing community, died from cancer just before the track's 55th annual Easter Sunday Funny Car Classic. She and her alcohol-fueled, brutally loud, and impossibly fast Funny Car had been mainstays at the event from virtually the beginning. Fans adored her, filling the grandstands and scooping up T-shirts, worn-out and signed engine parts, and other souvenirs at her stand in pits.

Bunny Burkett (holding dog) with an assistant in her souvenir stand. Sales, which were always brisk at Eastside, contributed significantly to her team's budget. Easter Sunday, 2006. Bottom: Bunny Burkett in her Alcohol Funny Car does a burnout just before racing her opponent, in the far lane, down the track. Fans love burnouts — the louder and smoker the better. Easter Sunday, 2009. Burkett passed away in April 2020.

The violence surrounding the protests over the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer only adds to my gloom. Uniformed agents of the state have sparked, escalated, and perpetrated much of it, assaulting protesters that they seem to see as the enemy, rather than as members of the public they're sworn to serve.

All of this could make a mockery of the name I gave to this project many years ago: “Democracy of Speed”. It sounds too optimistic for these times, and optimistic is how I mean it. Eastside, I thought, showed me America at its best. It was a place where black folks and white folks formed a genuine community of friends — a "family," they almost invariably called it — dedicated to the fine art of making cars go fast. The community has unspoken rules. One of them is that what's inside the track stays inside, and what's outside stays outside. Many of the friendships, genuine though they are, don't extend beyond the track. This is particularly true of the interracial ones. Politics is another silent taboo. In the years since I was a constant presence at Eastside, Trump's candidacy and presidency, with their appeals to white nationalism, have strained some friendships. Although there's little political talk at the track, black members of the community inevitably see their white friends' posts on Facebook. Many have been pro-Trump; a few were antiblack.

Racing is what matters most, however, and, at this start of this interrupted season, it was clear that the community endures.

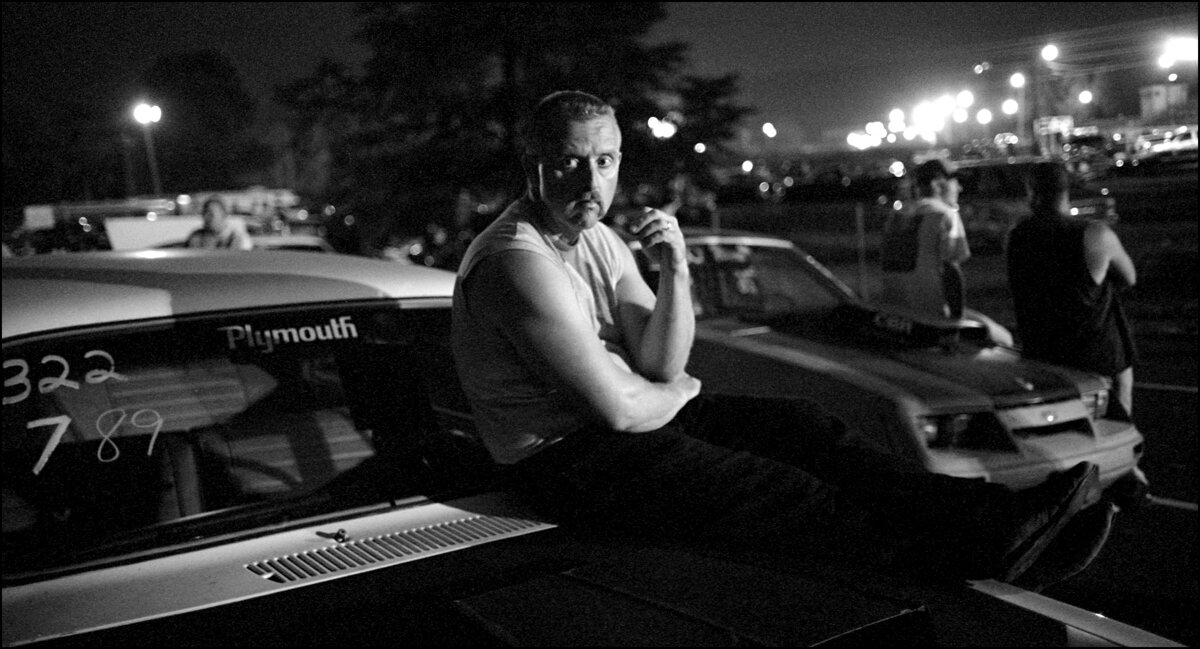

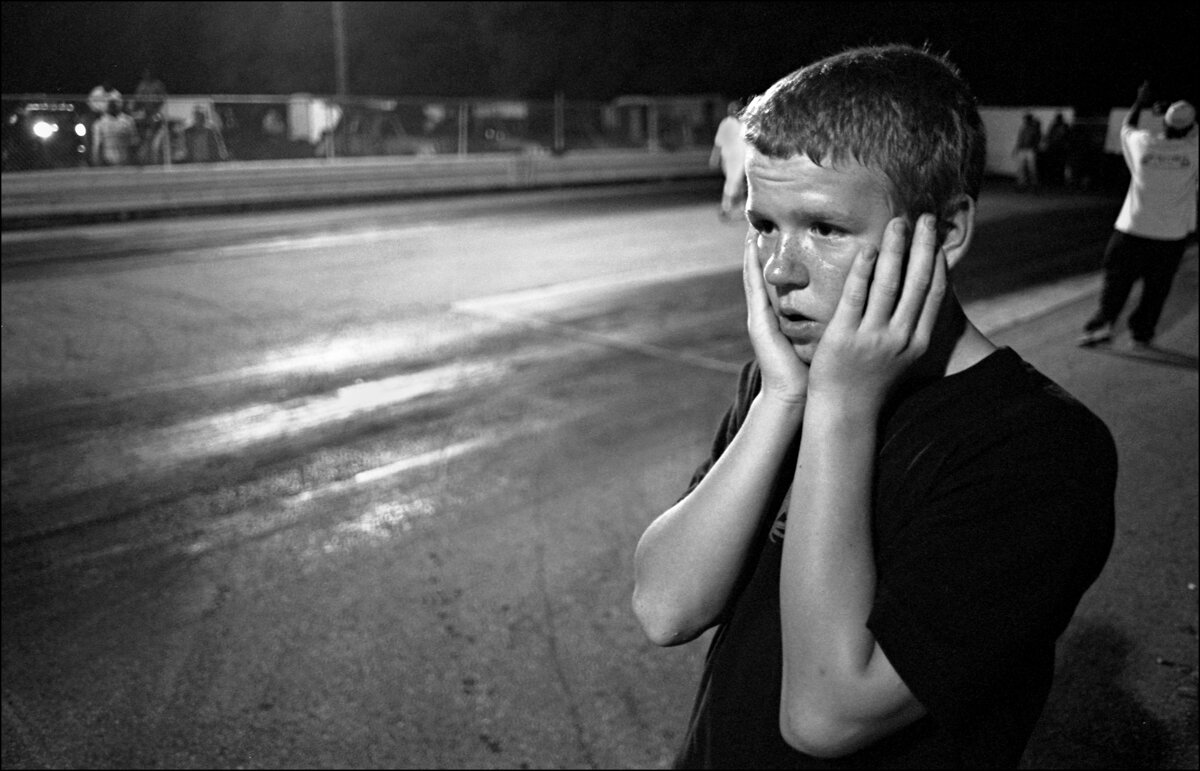

I wasn't entirely wrong about what I'd find at Eastside, when I first drove out on a summer's afternoon in 2002. The track was dirty, smelly, smoky, and loud. (I learned, quickly enough, that was half the attraction.) And there were cool pictures to be made. At first, I focused on the racing — the cars, the motorcycles, and all that smoke. But I was more interested in the people, and, as we got to know each other, more and more of my photos were about them.

Bunny Burkett, kneeling in prayer before her first pass down the track in her Alcohol Funny Car. Burkett credited her recovery from the life-threatening injuries she sustained in a 1995 racing accident to her faith in God. Easter Sunday, 2011. Members of Bunny Burkett's racing team gather in a circle to pray prior to the first race of the day. Easter Sunday, 2011.

The racing at Eastside is on a ⅛-mile track, one of the standard lengths for dragstrips. They divide cars into three classes, depending on speed. In the slowest of the classes, Street Eliminator (which is still very fast), racers sometimes drive the car they'll take to work on Monday morning. Drivers in the Super Pro class, the fastest, have often spent well over $100,000 on a car that will take them down the track in less than four seconds, at over 150 miles per hour. That's about twice as fast as a Ferrari could do it. There are separate classes for motorcycles and Jr. Dragsters, for racers under 18 years old. (The rules impose speed restrictions on Jr. Dragsters.)

Many of the Jr. Dragster racers I met when I began the project now have families and children of their own. “Democracy of Speed” is that old. It feels like history, now, something that Bunny Burkett's death confirms. But the name remains the same as it was almost two decades ago. That's because the drag racing community at Eastside, for all its limitations, has come closer to fulfilling the promise of equality than the country as a whole. Even in times like the present, I like to think it offers a glimpse of America's future.

John Edwin Mason teaches African history and the history of photography at the University of Virginia. He has written extensively on South African social and cultural history and on photography in Africa and the United States. He is now working on a book about the American photographer, writer, and filmmaker Gordon Parks.