Words by Dr. Grace Bagwell Adams

Dr. Grace Bagwell Adams is a public health expert, professor, and mother. She submitted this essay to The Bitter Southerner as a righteous call to anger — a professional and personal take on one of the most urgent situations our country has faced in decades.

October 30, 2025

On Saturday, November 1, 42 million Americans will be cut off from the lifeline that keeps their families from starving: SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the federal program formerly known as Food Stamps). The South, where so many folks already live on the margin, will be one of the hardest-hit areas. More than 40 percent of all SNAP-receiving households in the United States live in our region — a higher percentage than in any other part of the country. In just a few days, this new hardship will hit the bank accounts and dinner tables of SNAP recipients in a tsunami that will have ripple effects in our grocery stores and throughout the economy. The whole country is being held hostage by federal politicians, but the ransom is higher for the South. We have more to lose here.

The humility and time-sensitivity of these conditions is real and connects to my professional reason for writing this essay. Here in Athens, I’m a professor of health and social policy at the University of Georgia. My favorite supper to this day is pinto beans and biscuits with onion and chow chow on the side. It tastes like home, and I honestly still prefer beans over a steak dinner. But I also know it’s one of the hallmark meals of the South because it was one of the most filling ways to stretch a dollar, a dish that could feed large families.

The South has always maintained a strange intimacy with hunger. We know what it means to make something out of nothing, to turn scraps into supper, to feed whoever shows up at the table. This is part of the sacredness of Southern survival — potluck generosity that has kept families alive for generations.

There is another side of this coin, though. It’s the side that is frightening to me. We’ve come to not only accept hunger, but to expect it in the South. Maybe this is why we can stomach, quite literally, the idea that the politicians we elect to represent our families are the ones that are ripping down the very programs that keep us from starving to death.

I write from both professional expertise and personal connection. Hunger is written into my genetic memory. My family’s story begins on a small farm in Enoree, South Carolina, where my grandmother and my namesake, Grace West O’Shields, was born in 1918. The eldest of 11 children, she came of age in the iron grip of the Great Depression and spent her adolescence caring for her 10 siblings, while her mother, Minnie, cycled in and out of institutions for “mental breakdowns.”

Years later, while I was in graduate school studying poverty and food insecurity, my mother called with a realization that connected our history to my work: “Gracie,” she said, “your Great-Grandma Minnie had pellagra. It made her mentally ill.”

Pellagra. A disease once endemic to the rural South, driven by poverty and a lack of niacin (vitamin B3) in everyday diets. Untreated, niacin deficiency and resulting pellagra can cause mental health symptoms, including mania, psychosis, and dementia. In the early 20th century, pellagra appeared anywhere poverty and poor nutrition collided — in textile towns across the Carolinas, in the mining camps of West Virginia, in tenements from Chicago to New York. My great-grandmother Minnie lost her mind to hunger. Many others lost their lives.

That conversation with my mother revealed a hard truth: I am one generation removed from the kind of hunger that breaks both body and mind. My grandmother lost her mother to mental illness and her childhood to caregiving because of food insecurity. Now, 100 years later, we stand on the edge of the same precipice.

I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the SNAP program and how it mitigates hunger for low-income families. I spent my first seven years as an academic researcher looking at every aspect of this food assistance program — how it functions, who it serves, how it might be improved, what barriers are present to participation, and how families perceive and experience the process of applying.

I’ve come to a few meaningful conclusions. First and foremost, SNAP is essential to poor families. The average $300 a month received by a family provides about $75 a week to buy food. This support keeps the worst effects of starvation at bay, but it rarely, if ever, stops recipients from completely going hungry. Second, SNAP is typically used by families who are the “working poor,” those piecing together multiple jobs to survive. And these households, more often than not, include children, older adults, and/or people with disabilities. Third, and somewhat surprising to most, is that SNAP is an economic stimulus. Families who get these benefits do not keep them in their bank accounts, as they aren’t able to spend the benefit on other goods. These dollars are spent in grocery stores and are often the engine of our food economy, especially in rural and low-income neighborhoods. Every dollar given to a family on SNAP supports the local food economy.

SNAP is just one casualty of the government shutdown. Many more programs that barely facilitate survival for low-income families are also paused or gutted completely. Among them are WIC, the nutrition program for babies and their mamas that serves 40 percent of infants born in the United States. Any parent who has heard the cry of their hungry child knows it’s a sound you want to respond to immediately. Imagine not having enough food to soothe your child. Without vouchers, breastfeeding mamas won’t be able to buy the whole, nutrient-dense foods that allow their bodies to produce milk. Parents using vouchers to purchase formula won’t have access to that, either.

SNAP and WIC were never designed to solve the problem of poverty or to eliminate all food insecurity. They were, however, designed to ameliorate the very worst effects of privation. Quite literally, they exist to prevent people from starving to death. In the richest nation in the world, a substantial portion of our citizens, even with these programs fully funded and functioning, are hungry on a daily basis. Now, with SNAP and WIC unavailable, millions will be pushed beyond the brink.

The domino effect of such a shift will have near-immediate impacts on these families’ abilities to pay their rent or mortgages, too. Evictions will go up. So will emergency room use. When a family has to choose between putting food in their children’s mouths and keeping a roof over their heads, some desperate decisions will become necessary. When these same families — many of whom have Type 2 diabetes diagnoses or other chronic conditions that require careful management — don’t have access to consistent, nutritious food, some will experience blood glucose shocks or other crises that will land them in the hospital. Other dominos will also fall. Families will have to make a myriad of choices like whether to put gas in the car, take their sick baby to the doctor, get their prescription filled, or buy groceries. Each of the choices will gnaw at their bellies and consciences as they try to do what’s “best” and “right” by the loved ones in their home. There is no “best,” though, there is only survival.

In my classroom, I teach policy students to understand the “counterfactual.” This is a fancy word for an ancient concept, which is best understood by asking a simple question: What would the state of the world be if the policy had never happened? In this case, the SNAP counterfactual is a South that would have seen preventable diseases like pellagra — which plagued my own great- grandmother — persist in the population until modern times, with far greater and worse effects as transfers of poverty and disease are passed down from generation to generation. My concern is that without SNAP and WIC, this will become our reality again in the very near future. Our nation could revert back to Depression-era levels of hunger and starvation.

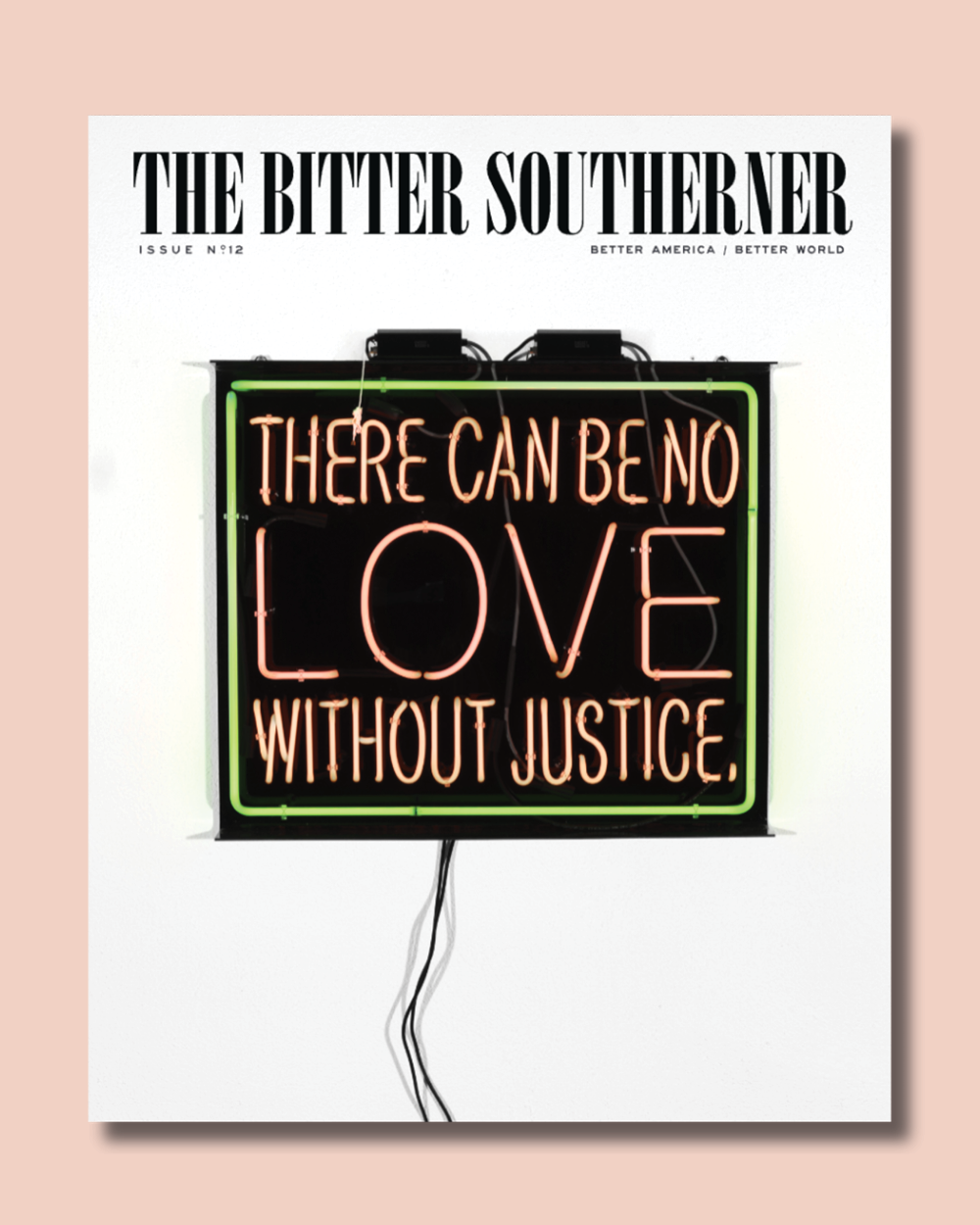

So this is my call to righteous anger. The call to wake up and realize what is happening to our families, our children, our communities. A call to stop blaming people who don’t vote like you and instead join hands to fight against both hunger and our inept politicians. A call to see, with clear eyes, that every empty plate is a policy choice.

Many families will sit at tables today where there is too little, or worse yet, no food. Hunger is not a monolith — it looks different from household to household. But it almost always involves shame, grief, pain, suffering, and sacrifice. The families in our communities who are going hungry are not strangers; they are our neighbors and our friends. We cannot be complacent and allow the dam to burst, as the life rafts that have held us afloat drift away. Call your representatives in Congress and let them know — We are angry. And we will not tolerate allowing even one family in our midst going hungry.