The Folklore Project

Phoenicia, New York

My Racist Friend

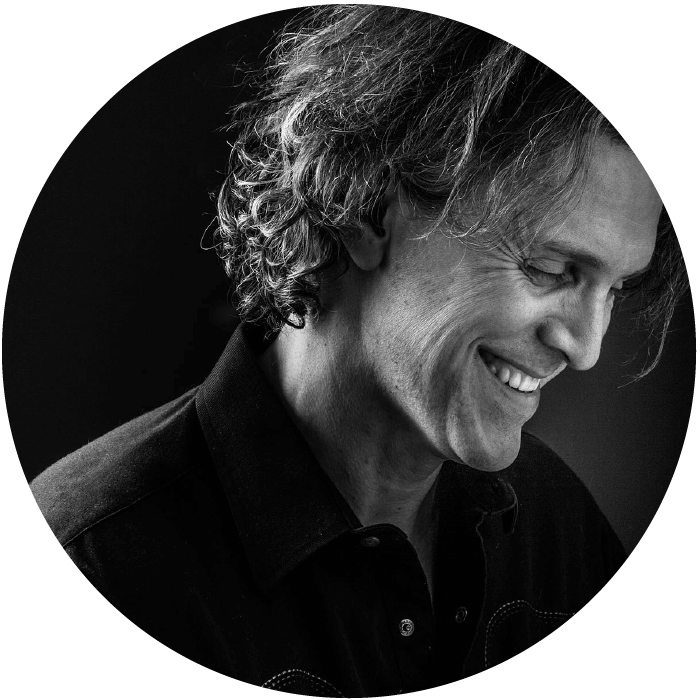

By Robert Burke Warren

When I see the hate-filled faces of the neo-Nazis, Ku Klux Klan, and assorted white supremacists, I feel revulsion, anxiety, and sadness. I also feel familiarity. Like most white Southerners, my family tree contains a carefully taught, particularly intense fear of difference.

My maternal grandmother, Gammie, was in the United Daughters of the Confederacy – her grandfather, Josephus Camp Sr., fought for the South – and she cleaved to the “Gone With the Wind” fantasy of “the good old days” of Dixie: The Civil War was about state’s rights, the generals were men of honor with rebel spirits, slaves were often “family,” and the Jim Crow South was when “everyone knew their place,” etc. You can boil down all of the above to fear, learned at her daddy’s knee: fear of difference and desire to remain separate from and feel superior to that which is feared.

My estranged father died driving drunk in 1972, when I was 7, and my mother, Mary, never remarried, so she depended on Gammie to help raise my brother and me. For that, we were lucky. Gammie loved us, we loved her, she showed up. It pains me to write anything negative about her, lest she be reduced to something she was not. But in truth, among many other things, she was an apologist for the Confederacy.

Interestingly, although raised Southern Baptist, Gammie married and bore the children of Salvatore “Sam” Lucchese, my grandfather, a Sicilian Catholic son of immigrants and lifelong Democrat, not a racist. Her distraught mother would only ever refer to him as “the wop.” I like to tell myself that an unconscious yet engaged part of Gammie, a genuinely good and brave element discouraged and suppressed by her forebears, sought to commingle her DNA with Sam’s to begin the process of breaking the cycle of racism, of hate. If so, it worked. Mostly.

My mom, a baby boomer, rebelled against her upbringing. She exposed my brother and me to narratives and morals wildly different from what we saw and heard in Gammie’s house. We were hippie kids, grubby, longhaired, and barefoot, raised feminist (in our house, at least), taught that the absolute worst word in the world was nigger. (To this day, I have a visceral reaction when I hear it.) Mom presented the rising multiculturalism of post-Civil Rights Act Atlanta as something to embrace. And embrace it we did.

The times were on Mom’s side. The 1973 election of Atlanta’s first African-American mayor, Maynard Jackson, signaled a shift that felt as normal to me as a change in season. We enjoyed the brief, post-Watergate, welcome novelty of our state’s former governor, Jimmy Carter, an erstwhile peanut farmer and blue-collar Democrat, rising to the White House in 1976. Other aspects of this environment that shaped us were integrated schools, friends and teachers of color, Jewish neighbors, queer neighbors, immigrant-owned businesses, and pervasive, genre-bending, rainbow-fueled music. Gammie’s politics didn’t stand a chance. They actually made no sense.

Yet somehow, I strayed. For years, when I’ve told the story I concoct of my life, I’ve omitted an aberrant period of a year or so, when I rebelled against my mother’s rebellion. From age 12 to 13, I ran with a rich, charismatic, racist kid. I’ll call him Ricky Green. Today, when I see the so-called alt-right, I see Ricky, and I cringe at the version of myself that maintained a friendship with a kid who routinely said nigger, even as I protested. Especially as I protested.

I wonder why, exactly, I put up with it, as I didn’t before and haven’t since. I can say this: As a child, I was often afraid, obsessed with thoughts of death, made all the more intimate by losing my dad, having him here one day, gone forever the next. I was acutely aware of my connection to other people, and the prospect of another rupture terrified me.

Ricky Green’s cardinal trait was a dumb kind of fearlessness, and engaging with that helped alleviate my fears, of that I’m sure. To 13-year-old me, his racism was worth the payoff of feeling unafraid. Until it wasn’t.

Ricky’s and my story began in the summer between seventh and eighth grade – the summer of ’78. Abruptly, our shoulders had broadened, we’d grown taller, and girls bloomed all around us. They paid particular attention to sandy-haired, movie-star handsome, foulmouthed Ricky, who was not yet my friend, though we’d attended the same school for years. Even as he gleefully popped their bra straps, I noticed how girls nevertheless drank him in, how they convulsively giggled at his quips. How everyone gasped as he talked back to the teacher, even as that teacher hit him with a hockey stick, and pulled him, still seated at his desk, by his hair across the classroom. All the while, Ricky just laughed.

Soon after the hockey-stick incident, Ricky seemed to sense my admiration, and invited me to his house. On the way home, we stopped at the Majik Market to play the Kiss pinball machine. Ricky mercilessly made fun of the Pakistani counter guy’s accent (behind his back). My face went hot with shame, but Ricky’s magnetism won out. Even as he whispered nigger in my ear when we passed an African-American man on the sidewalk – in part because it upset me, which he found hilarious – I continued hanging out with him.

Like me, Ricky was a latchkey kid. His successful attorney father – who I never saw – had divorced his mother, and she was either not at their splendid, pine-shrouded home in an upscale neighborhood, or she was asleep in her upstairs bedroom, or, as Ricky said, she was “at the fat farm,” leaving us the run of the place. I have no recollections of her present as we raided the pantry, and/or watched R-rated movies – Ricky called them “fuck movies” – on HBO. (The Greens were the only family I knew with HBO.) She slept so soundly, Ricky could sneak into her room and grab her car keys from her pocketbook.

“Let’s go for a ride in the Caddy!” he said, laughing. “You gotta help me push it into the street, though.”

“You can drive?”

“Fuck yes, I can. I’ll drive us to Kathy’s house. Ally’s there. It’ll be like the panty raid on ‘Happy Days’!”

Of course I helped. In the wee hours of the morning, we pushed his mom’s 1979 Cadillac DeVille down their driveway and into the street. I hopped in as Ricky started it up, wrestling with my nerves as he caromed through the suburbs, wind in his hair, laughing, radio blasting Styx and Kansas. We had no drugs or alcohol, just Ricky’s contagious bravado, perhaps the most potent intoxicant I’ve ever imbibed.

Incredibly, we got away with it. This further emboldened us to joyride several times that summer, two 13-year-old boys in a Cadillac in the dead of night, dropping in on girls having sleepovers. We were never caught.

Eventually, Ricky got his hands on a bag of pot, and we began to get high, which dampened the impulse to sneak out the Caddy. We just sat around smoking joints, watching HBO, and eating junk food. As I dragged on the joint, Ricky was fond of saying, “Don’t nigger-lip it!”

Later, while smoking a joint with my friend Johnny and his much older, disco dandy brother, Gus, I aped Ricky. I said, “Don’t nigger-lip it!” This was the only time in my life I’ve used that word. Gus and Johnny’s parents had emigrated from Cuba, and I thought Gus was the coolest. He said, “Don’t say that, man. I got a lotta black friends.” He seemed personally hurt, disappointed.

In that moment – an older person acting parental, calling me out, caring – something shifted. It would take a night of wingin’ for me to fully awaken.

Wingin’ entailed hiding in bushes and hurling rocks at cars. These episodes pain me the most, even more than my wimpy protests to the word nigger. Because we endangered people. For fun. The night our mutual friend – I’ll call him Jim – joined us, things escalated. Jim was particularly insecure, desperate to be liked, and would do anything Ricky asked. After a few volleys of rocks at cars, followed by running into the woods, Ricky held up an aluminum baseball bat.

“Wing this at the next car,” Ricky said to Jim.

Jim readily agreed, laughing maniacally. Soon, a Volkswagen Bug much like my mom’s headed our way. Jim flung the bat as hard as he could and it slammed into the car door with a resonant bang. The car screeched to a halt, and we bolted into the woods by Ricky’s house.

Instead of my usual adrenal euphoria, I felt a cold wave of guilt. Clueless Jim and Ricky cackled, pushing pine branches out of the way, and once again, we escaped retribution. But for me, the thrill was gone. Was it because the VW reminded me of my mom and reignited what she’d taught me, clarified my shame? Perhaps.

Soon after, Jim told me Ricky was sick of me talking about my dad’s death. My father had been gone for six years, and to my horror, memories of him were fading. And I did, in fact, often mention him as a means of keeping his memory alive and, honestly, to gin up sympathy. As sad as that seems now, I can actually understand how it could irritate a 13-year-old. But at the time, I seized on Ricky’s insensitivity toward my grief; I would use it to sever ties. This particular affront produced actionable rage. I challenged him to a fight next to the tire swings at school.

“Don’t say shit about my dad,” I said, as kids gathered to watch.

“I didn’t say shit about your dad!” Ricky said.

Ricky and I grappled and swung for about 10 seconds before a teacher broke it up, and gave us a talking to. The teacher made us shake hands, and Ricky said, “Can we be friends again now?” I nodded, but we both knew it was over.

Summer came. I kept to myself. I slept on our screened-in porch, and rode my bike all over Atlanta in the middle of the night, thinking about finally learning to play bass. I’d been procrastinating picking up an instrument, resisting a pull from my future, but I was about to give in. One night, riding in the middle of a deserted road, I nearly wept with sweet anticipation, a sense of destiny. Mom bought me a plywood starter bass, and I immediately devoted myself to it. Within three years, I would be gigging in clubs, a working musician.

The last time I saw Ricky was junior year of high school. He was hanging out with the druggies, waving to me from the smoking area, a glazed Cheech & Chong expression on his face. He would soon either drop out or transfer. Years passed, I moved to New York, and my time with the racist kid faded, in part because I was loath to revisit it, afraid of being judged for having been so cowardly. My brother occasionally crossed paths with Ricky, though, and reported that he had become a restorer of old Atlanta houses, but had subsequently developed an anxiety disorder, become addicted to Xanax, and never left his home. A couple years ago, I learned Ricky committed suicide.

Had he changed in those post-school years? I do not know. Truthfully, I hadn’t thought much about him until I saw those young white supremacists marching, and I recalled childhood time spent with Ricky, thinking we were invulnerable. The pleasure I experienced in his company was in feeling unconnected to others, until I woke up to the painful, beautiful fact that no one really is.

Robert Burke Warren is a writer, performer, and musician. He was one of The Bitter Southerner’s earliest contributors, with his story “Southern Belles, Latchkey Kids & Thrift-Store Crossdressers.” His work has also appeared in Paste, Salon, The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Texas Music, Brooklyn Parent, Woodstock Times, Vulture, The Rumpus, and the Da Capo anthology “The Show I‘ll Never Forget.” He's ghostwritten for Gregg Allman, and his debut novel, “Perfectly Broken,” was just released in paperback. As a songwriter, he has released seven CDs – two as Robert Burke Warren and five as family musician Uncle Rock. His music appears on albums by Rosanne Cash, RuPaul, and rockabilly queen Wanda Jackson. In the mid ’90s, he portrayed Buddy Holly in the West End musical “Buddy: the Buddy Holly Story.” Prior to that he traveled the world as a rock and roll bass player. He came of age in Atlanta, became a man in New York City, and now lives, works, and serves on the school board in rural Phoenicia, New York.