The Folklore Project

Atlanta, Georgia

The Leader of the Band

By Timothy Cook

Dad was born in Quanah, Texas, in 1933.

He was the son of a sharecropper and a woman who taught in a one-room schoolhouse. His early years were spent picking cotton, helping around the farm with the cows and the hen house and the hogs and, later, following the wheat harvest into North and South Dakota.

When his number came up for the draft, he enlisted and took part in the Korean conflict, which it seems we are still fighting today. Because he did not want to fight or kill anyone but was delighted to serve, Dad soon joined the Army Band. He played the saxophone and clarinet.

The band performed at important ceremonies and kept up the soldiers’ spirits. To him, that was as important as all the killing. Returning to Quanah after his service, he was soon teaching music for the McLean school district, where he met his future wife after her storied and heroic career with Tulia High School.

She was the school's beloved drama teacher. When they first started dating (and probably still today), Tulia was a "dusty nothing" of a small town and people were super nosy, so they had their first few dates at cafes near Amarillo, just in case things didn't work out between them.

When they eventually announced their wedding in 1965, the band, the chorus, and the drama students surprised them by interrupting their rehearsal of "The Unsinkable Molly Brown" with a wedding processional.

Bruce, Tim, and Sean Cook

In 1966, Dad followed his college roommate (whom he was friends with until his passing in 2014) to Clemson University, where he soon became the assistant band director, then director of the marching band program. The early years were tough, as the band was mostly an afterthought. Clemson was a former military school that had evolved into an agricultural and engineering powerhouse.

Many times, I believe, Dad thought about quitting, returning to Texas and farming, or possibly teaching again at a tiny high school. Life would have been so much simpler. I still remember angry phone calls from locals who were annoyed that the band practiced across the street from their houses.

"I can't even hear ‘General Hospital.’"

Until the football team started winning. They started winning a lot. So much that in 1981, under Danny Ford's leadership, Clemson won the national championship. Tainted by hints of corruption, Danny Ford was eventually ousted. To this day though, he remains a local hero,and folks in the community still catch glimpses of him at Dyar's Diner.

The national championship?

Yeah, I can still vividly remember the steamy, oppressive night in Miami where the Tigers surprised the Nebraska Cornhuskers — and the world, for that matter.

And, just like that, Clemson was on the map.

Sports commentators, who had no idea where Clemson was, frequently mispronounced its name, referring to it as "Clemzon," when everyone else who mattered to me pronounced it "Clempson."

As you might imagine, I didn't have much of a chance to see dad from 1981 and that national championship until his retirement in the late 1990s. On the weekends, I'd look for the top of his head (he had a bald spot that always burned to a crisp) from the bleachers, yards and yards away in the distance.

When the team travelled, especially to bowl games, Dad would do his best to take us with him. But again, I only saw him from afar. He was usually busy babysitting our 200 to 300 surrogate brothers and sisters.

They all loved him, and so did we, but I longed for something different. I wanted to know this man who was my father. For years, I begged him to tell me stories from his youth — jackrabbits, ornery cows, tractor belts, hogs, and chickens. His early life of subsistence seemed both difficult and magical to me. I wanted to know more about it. To me, it was what made my dad the man who everyone loved at Clemson.

He talked about as much as he could remember. But, as he told me in late 2013, "I can remember 1935 like it was yesterday,but don't ask me to remember what I ate for breakfast."

Such is the case for so many of our heroes.

You can only hope that someone else captured the moments for you, so that you could at least dream about people, times, places, and events you wish you'd been part of.

In 2012 to early 2013 dad was struck with an extremely rare and incurable blood cancer. During the year and a half when he tried desperately to live, he saw the beginnings of a memorial practice field, being built to honor him and his college classmate.

We talked on the phone almost daily. I've got that to hold onto.

"What's up?" I'd ask, with hope that whatever he was doing brought him pleasure.

"Marking time," he'd respond, but he'd thank me for calling, and we'd talk for at least 10 or 15 minutes,about what he thought was nothing.

To me, it was everything, and the most I could hope for.

I wanted him to beat cancer so badly I convinced myself that if I could feel better about his ailments, somehow he'd keep living and we'd talk about the things that I had begged to know about since childhood.

I can still remember sitting in the serenity garden of a local counseling center, talking to him over the phone. It was the day when he was told by his doctors that the end was nigh, and that they were very sorry. The most beautiful, tragic, and horrible day of my life.

I had spent the entire year leading up to his death trying to feel better about it, and before you know it, we were with him in hospice.

Word got out that he was dying, and there was a steady stream of well-wishers who either came to see him or sent handwritten letters.

We read the letters to him while he slept.

I guess they were more for us than anyone.

The moment he passed, a beautiful red cardinal lit on the window outside his room. I had heard that meant an angel had come to collect him.

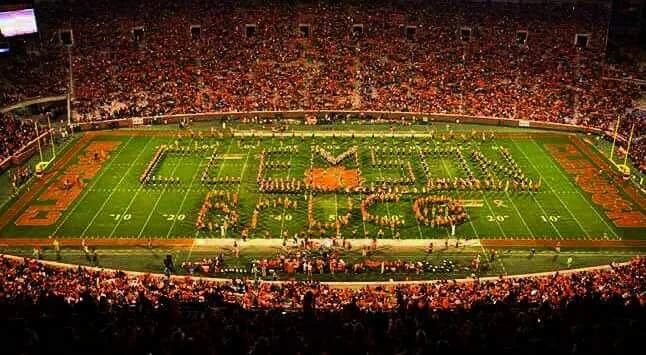

His memorial tribute was in front of 85,000 Clemson fans at a game between Clemson and Syracuse. My entire family sat in the president's box at the stadium, and we watched as the alumni band spelled his name as they marched off the field to “Tiger Rag,” a song he'd heard thousands of times in his lifetime.

They even flashed his picture on the big screen for a moment.

I could hear mom three rows back, clapping and saying, "Yay, Bruce," as the band exited the field.

And for a moment, Dad, who wasn't even there to see it, received the acknowledgement of his lifetime achievement.

I miss him greatly, as I'm sure you imagine. He's in the cemetery, a few hundred yards from the stadium.

And get this — and I know it's kind of hokey — but his tombstone came from the local Jockey Lot (flea market) that he often frequented with another of his good friends on the weekends.

I still don't really know this man who I called my father. But I've got some good memories. Lots of them.

So, that's something. I’ll take it.