Burk Uzzle was 30 years old when he shot the most iconic images of 1969's Woodstock festival. By then, the North Carolina-born Uzzle was seven years into a career that would make him one of photojournalism's legends. Now, at age 80, he is back home in the South with a singular focus — to create images that help our region reconcile with its past.Story & Photograpy by Megan Dohm

The fields in Wilson, North Carolina, flatten out as they stretch east. The downtown district is small but lined with buildings from the town’s golden era, three or four stories high at the tallest. A hundred years ago, the train brought booming business and a swinging party scene to a booming tobacco town. Now it is quieter, more domestic. The standout features are the old courthouse and the whirligig park. At the edge of downtown, there is an unassuming pair of warehouses, sharing a wall down the middle. The buildings once housed a casket factory, then a car dealership, then, sitting abandoned, a home for wildlife. They now serve as the home, gallery, archives, and studio of the photographer Burk Uzzle.

Born about fifty miles away from Wilson in Raleigh, Uzzle was raised all over the state, thanks to his father’s career as a civil engineer who moved on to a new project every three or four years. But the younger Uzzle says he got out of North Carolina as soon as he could — and he became, in 1961 at age 23, the youngest photographer ever hired to the staff of LIFE magazine. Afterward, he lived and worked around the globe.

But after nearly 60 years of lensing iconic images of many of our nation’s pivotal moments, he decided to come home to North Carolina, to this little town about an hour east of Raleigh, to continue his work.

Street view of downtown Wilson, North Carolina, Photo by Megan Dohm

Inside the gallery, it is all concrete and brick and plaster. The walls hold large prints of Uzzle’s work, evenly spaced. About every 15 minutes, the blast of a not-so-distant train whistle echoes in the rafters. Footsteps from the living area upstairs mark his partner Janet Kagan, going about her workday.

Uzzle’s recent work is lined near the gallery’s entry: the bright hats of church-going ladies propped onto tobacco stalks; children holding hands in an attitude of prayer while they face the camera and an AR-15 rifle placed in the foreground; a serene wedding portrait revisited 50 years after the couple’s marriage; a gang member named Theophilus photographed in light worthy of a late renaissance hero.

Burke Uzzle in his downtown Wilson, North Carolina studio, Photo by Megan Dohm

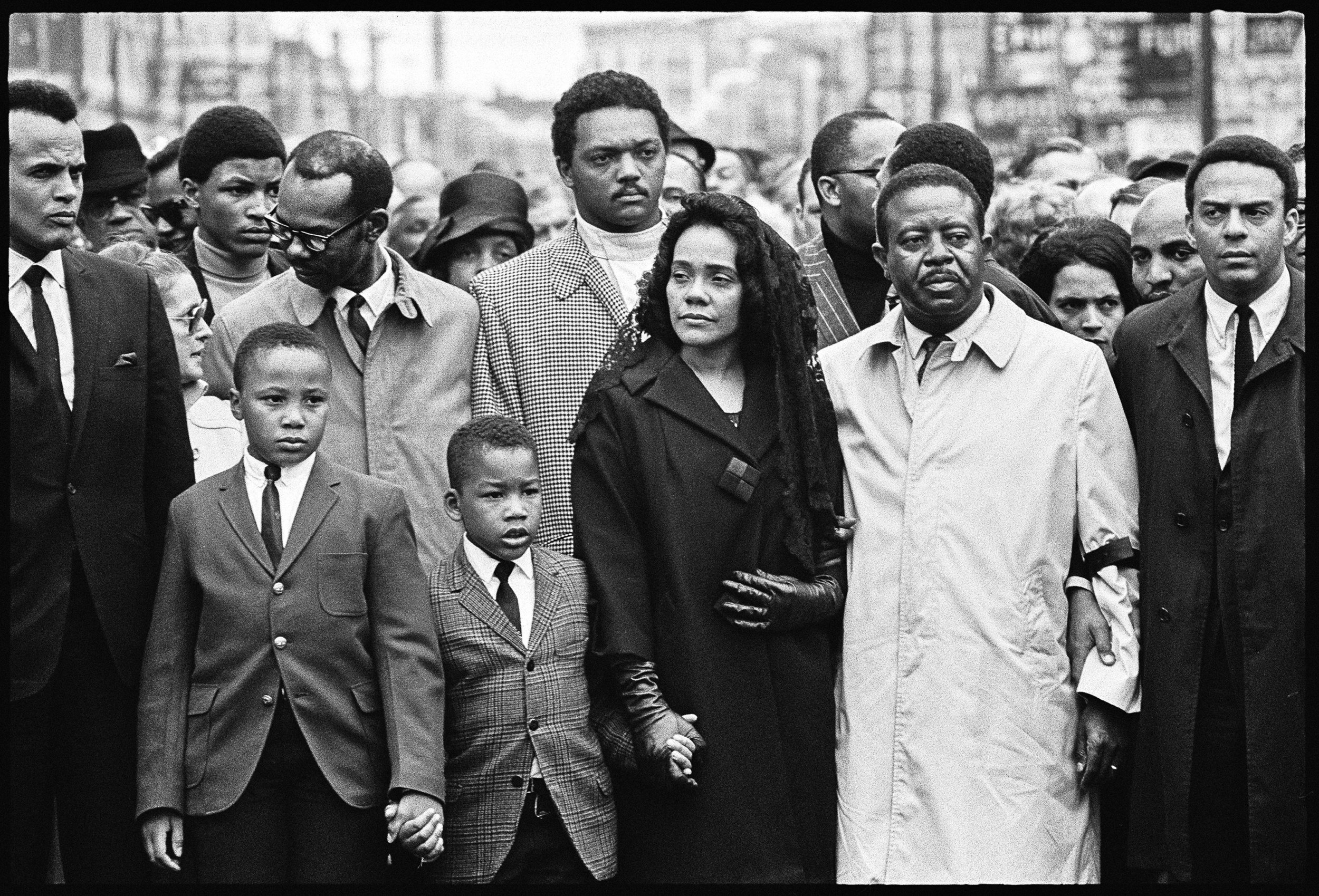

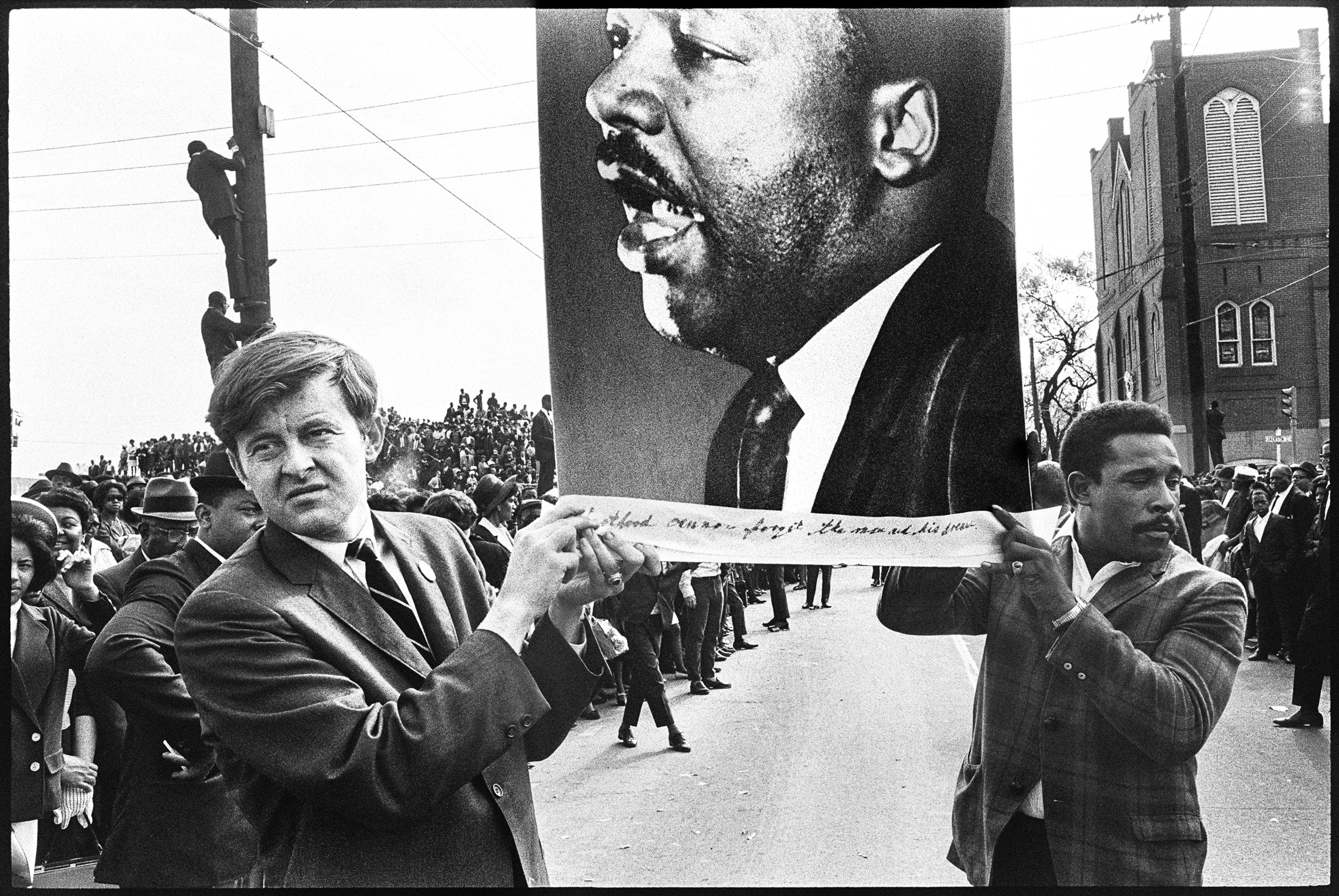

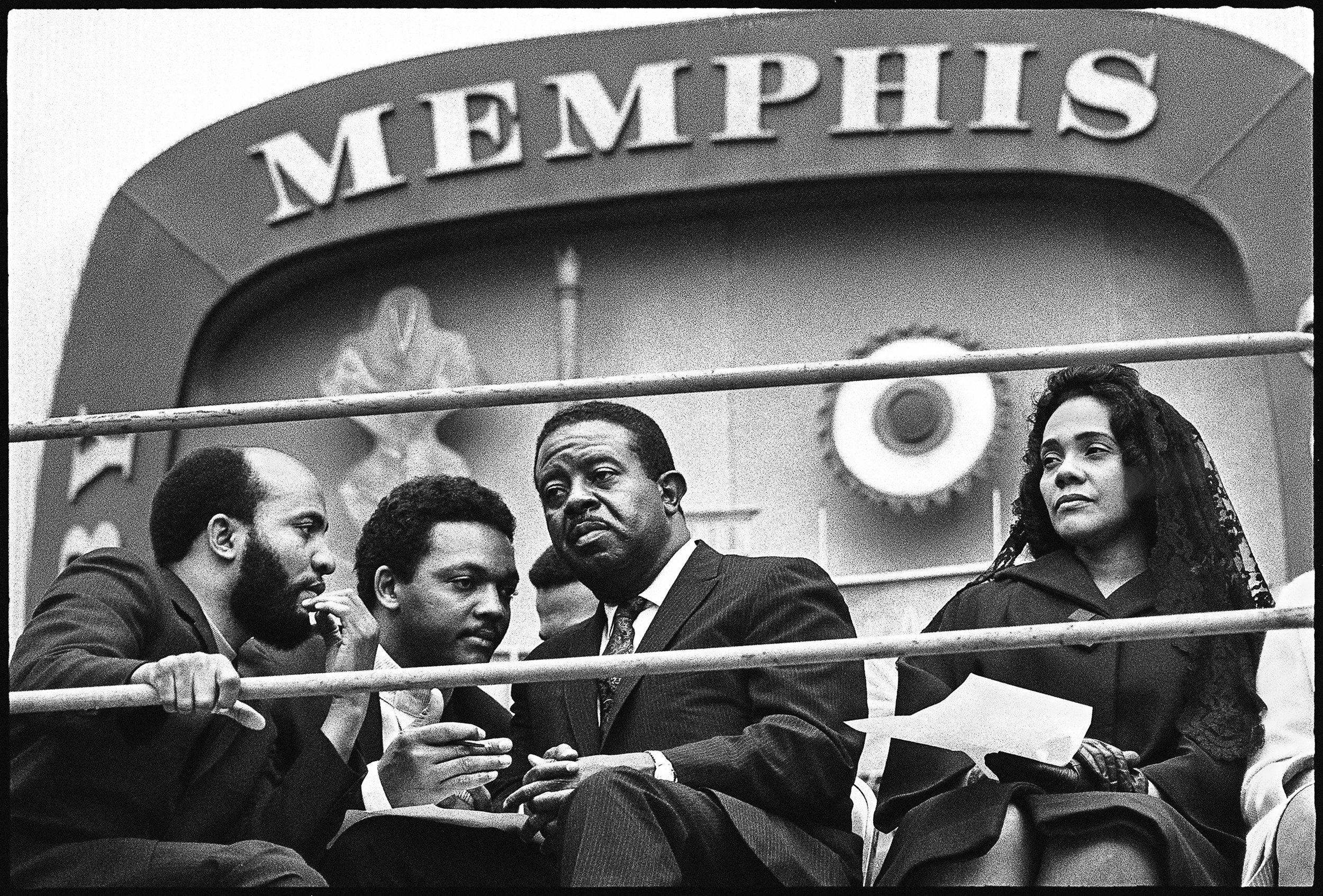

Eventually, these images fade into his older, more recognizable work. Following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, a mourner leans over his casket in Memphis, her hand resting on his cheek. Uzzle explained why this, instead of the image that landed on the cover of Newsweek, is what he chose to represent the time. He doesn’t have a drawl, but when he speaks, he is in no great hurry, either.

“There’s another picture in the same roll of film that wound up being the Newsweek cover the week he was killed, and that’s more of what you would expect [a woman sobbing from the shock of it all]. But the gentle caress comes from saying goodbye to a lover.” It’s a strength of Uzzle’s: understanding that what happens in the margins is often a clear indication of what is happening on the whole. He continues his walk along the gallery wall. “And then this is the Woodstock.” The image became the cover of the official live album of the concert, Woodstock: a couple standing amid fog and chaos, wrapped in each other and a blanket.

Woodstock Album Cover, Photo by Burk Uzzle

Growing up, Uzzle thought he would be a musician — maybe even a conductor.

“I was such a — still am — a skinny little runt,” he says. “A clarinet was something I could carry. You would not have wanted to hang a bass drum on me.”

That woodwind instrument became his first artistic pursuit, lessons bought with money squeezed from the grocery budget. School was a thing to be tolerated, but he would practice his music for three or four hours each afternoon.

“Music is what taught me discipline, without which I would never have been able to [do] what I’ve done in photography,” Uzzle says. To this day, if he hears a rendition of Madame Butterfly or Mahler’s Fourth Symphony on his car radio, he says he has no option but to pull over and give listening his full attention.

When his affections shifted from music to photography, his parents urged him not to give up his first love for an uncertain future. Still, they let him build a darkroom on the porch.

From his early teens, the goal was to be a photographer for LIFE, and the scrawny kid then living in Dunn, about an hour south of Raleigh, knew he had serious work to do. If anything newsworthy was happening in town, someone would know to tap Uzzle. Camera in the basket of his bicycle, he would pedal hard across town to catch everything on film. Particularly notable were the raids on backwoods stills: His first sip of alcohol was moonshine, straight from the coils. Following an afternoon at the scene, Uzzle would quickly develop the photos and stick them on the bus, addressed to the state papers. More often than not, his photographs would appear in print the next day. Before he had graduated from high school, Uzzle had a job offer from the Raleigh News & Observer.

At the age of 19, Uzzle married Cardy Best, the plucky daughter of a sharecropper. When she was seven months pregnant, they left the only “real” job he’d ever had to pursue bigger opportunities and connections in Atlanta. While working as another photographer’s assistant, his first magazine assignment found him. JET Magazine needed someone quickly to photograph a then up-and-coming preacher, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. This assignment and more assistant work bloomed and spread into other opportunities. Between jobs, Uzzle spent hours at the public library, pouring over every copy of LIFE ever published. By the end of his studies, he had a good idea of what made that magazine tick, and what his photographs should accomplish if he wanted to work there.

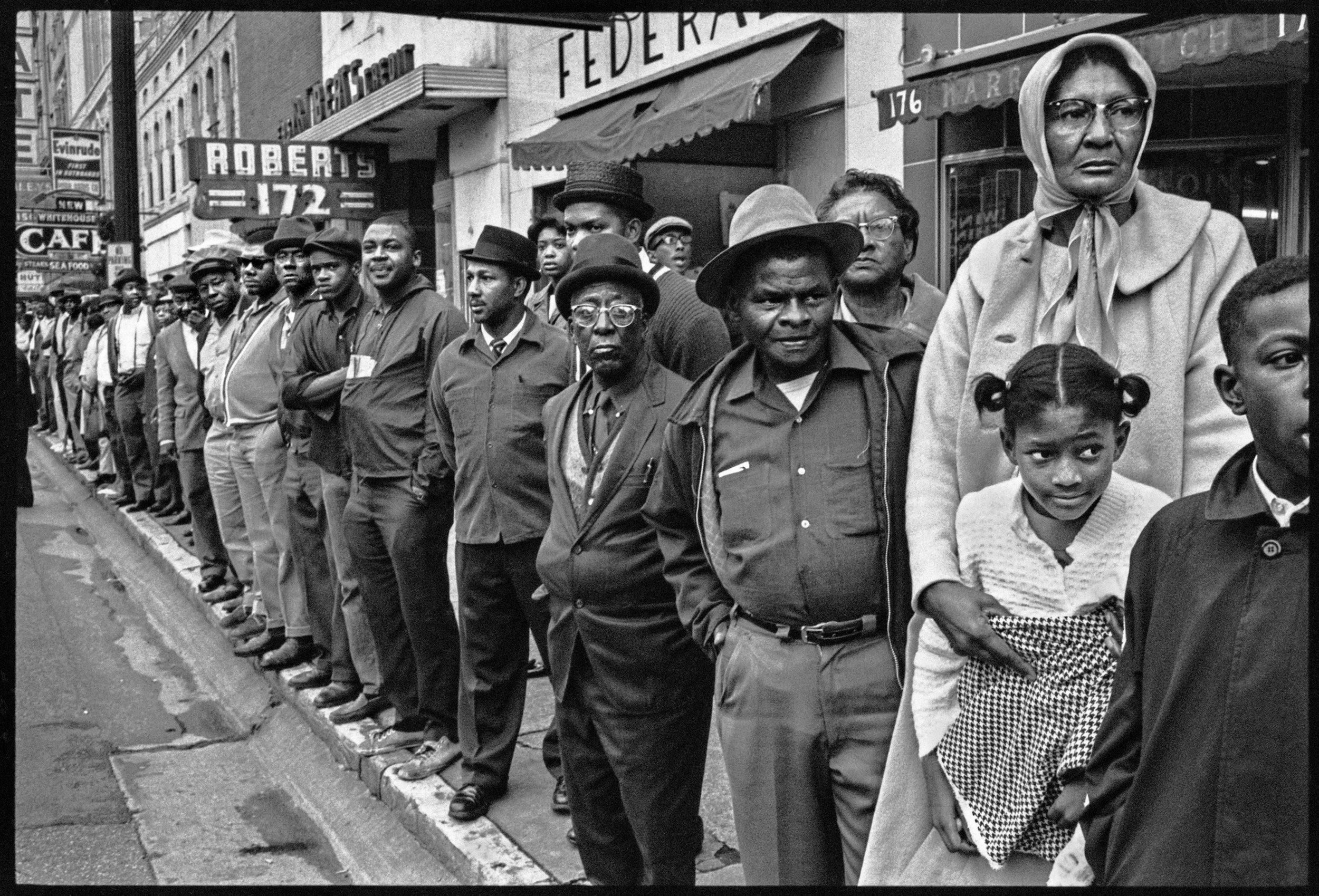

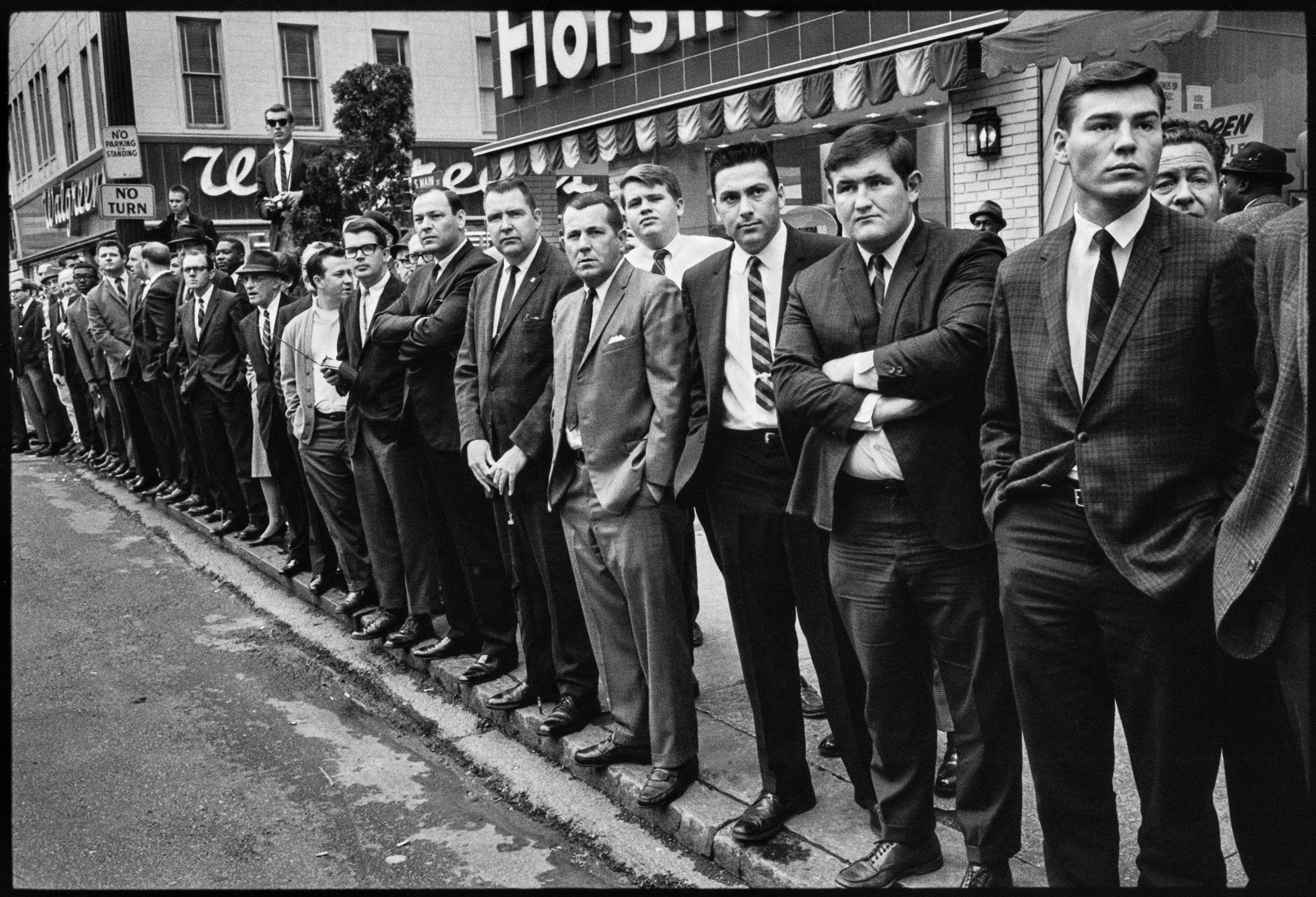

Photos by Burk Uzzle

In their Atlanta years, Burk and Cardy Uzzle experienced the birth of their two sons and the growth of his business. Then, the offer of a small retainer from a photography agency called the young family to Houston.

In Texas, as in Atlanta, Uzzle tried to make his presence known in LIFE’s bureau there. For some time, there were no openings, not even for a freelancer. The days in Houston were lean. The Uzzles had an apartment with one mattress, eating meals off of a closet shelf clamped into the window while seated on their suitcases. Uzzle persevered, working smaller assignments.

“But, one fine day he called up.” The call was from LIFE’s bureau chief in Dallas, who had a potential assignment for Uzzle. It required two grueling weeks on a sheep farm in Wyoming. But if he could ride a horse, the bureau chief said, there was a chance he could convince the higher-ups to give him a try. Uzzle assured the chief he was an experienced horseman, and won the job.

Burk Uzzle had never ridden a horse in his life. Equipped with a neighbor’s crash course on how to mount and hold the reins, Uzzle was put through a trial by fire thanks to a couple of wisecracking teen girls, a horse named Apple Blossom, and a gallop down the face of a Wyoming mountain. At the end of the time, he turned in about 200 rolls of film and held his breath. LIFE ran selections in a 10-page photo essay. After seeing more of his work, the photo editor of LIFE called the Dallas bureau chief, asking about Uzzle. What did the chief know about this guy who could cover both sheep and hard news?

“Well,” said the bureau chief, “he can barely speak English. He’s from the South. He’s a silly little thing — he’s got a crew-cut, speaks with a thick Southern accent, but he works hard. And he’s a good photographer.” This was enough to get Uzzle a plane ticket to LIFE headquarters in New York, and then — at 23 years old — a contract with the magazine.

Photo by megan dohm

Uzzle’s time with LIFE began at a rapid pace — starting with moving the whole family to Chicago. He was sent to South Dakota to cover a blizzard, and immediately afterward to Haiti to work undercover documenting a political uprising there (at times hiding his camera under a new sheepskin coat purchased to keep out the bitter cold of the South Dakota storm).

Traveling the globe for LIFE served as his higher education. The reporters he worked with were literary types, well educated and generous with their knowledge. On the rare occasion that partnering with a reporter was a problem, Uzzle would get lost in a crowd for an hour or 10. Early on, he earned a reputation of being a daredevil. During his time at LIFE, he snuck into a torture prison in Port-au-Prince, walked the streets of Paris, sweated with farmers in Mississippi, and came closest to losing a camera while crossing a river into Viet Cong territory, bullets whizzing past. He covered the eminent and the usually unseen.

“You can do anything — which is one of the curses of being young,” Uzzle says. “I don’t do that anymore, not at 80.”

photo by megan dohm

The ability and willingness to do anything often meant assignments others would balk at, like a Ku Klux Klan rally in the mountains of North Carolina. At the beginning of the racists’ gather, then-imperial wizard Robert Shelton made an announcement: There was a LIFE photographer in the crowd, with permission to be there. No one was to lay a hand on him. Uzzle says that without this announcement, any photographer would have had the daylights beaten out of him. Shooting roll after roll of film, Uzzle stashed the used film in his socks. Toward the end, he felt a large hand come from behind and hold his shoulder. Keeping his cool, Uzzle turned to find himself face-to-face with a man who was a former high school classmate.

“What are you doing here working for these awful people? Come on back to Dunn,” the acquaintance admonished him. Uzzle shrugged the offer away.

Over his career, Uzzle documented some of the most intimate, emotion-filled, and (sometimes literally) naked moments of people’s lives. His photographs, though, feel neither invasive nor exploitative. How does he achieve this?

“You spend time,” he answers simply. A well worked assignment is never a hit-and-run, he explains. The photographer must become part of the landscape and get to know the subject.

“You have enough meals with people, they know who you are,” he says. “You tell them about your kids and all that — so you’re just taking candid photographs and they’re not invasive.”

Photos by Burk Uzzle

As Uzzle’s work for LIFE grew, the photography world began to take notice. He developed friendships within Magnum Photos (to those familiar, simply “Magnum”), a large photo agency founded in New York in 1947. Magnum was one of the first photographers’ cooperatives, created to license photos for publication from a central location, allowing photographers to maintain the rights to their work and rub elbows with fellow practitioners. Widely varying artists called Magnum home, such as founding members Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, along with the likes of Ansel Adams, Elliot Erwitt, Martin Parr, and — eventually — Uzzle. On Uzzle’s second day in New York, Cornell Capa (an early member of Magnum and younger brother of Robert) took him aside with a piece of advice.

“He said, ‘Know two things: You’re only as good as your legs, and you’re only as good as your last picture. Don’t ever take anything for granted. You’ve got to work,’” Uzzle recalls “So I did. And I do now.”

photo by megan dohm

Uzzle was voted in as a full member of Magnum in 1967. Surrounded by some of the best photographers of the era, there was no option but to fine-tune his craft. While at Magnum, he continued to work at LIFE and studied every contact sheet Cartier-Bresson ever made. Cartier-Bresson is the father of candid photography as we know it. Almost every introductory photography class will include his images and his idea of the “decisive moment.” Cartier-Bresson became a mentor to Uzzle, going on walks with him and making sage suggestions.

“Spend time studying Caravaggio,” Henri (Henri, Uzzle calls him) would say. And had Uzzle considered composing from front to back, as well as left to right? The New York walks provided Uzzle with homework, readying him for future projects. Caravaggio was known for his use of sidelight — not like Rembrandt’s gently filtering rays, but more like divinely appointed lightning strikes - and for being a rascal. Both the divine lightning and scalawaggery suit Uzzle’s sensibilities. You can see the painterly influences in almost every photograph he displays. He ensures that every face has a well-established context, and that he can shape the light.

Woodstock Performer, Photo by Burk Uzzle

Uzzle tells of these legendary mentors, high adventures, and future hopes as he sits in his “digital darkroom.” He unfolds and refolds his limbs, sometimes leaning forward to make a point, looking owlish behind his geometric glasses. He tells of the places he has lived (Philadelphia, Houston, Atlanta, Chicago, New York, Daytona Beach, Seattle). And he tells how he decided that his work was calling him back southward, ending up in the small, quiet town of Wilson.

“I looked everywhere, drove all over the state, looked at every middle-sized town that might work,” he says of his search for a place to settle. “I went to Asheville, I went to the beach, and all the towns in between.” Asheville was too cold and the beach too close to rising water levels for comfort. He needed a safe place for his archives.

“Wilson is up high, it’s safe, and it’s affordable,” he says. “Very logically located to go anywhere you want to go.” He moved a few years before the death of his children’s mother, Cardy, of whom he speaks in glowing terms, despite their earlier divorce. After finding the warehouses, he restored them piece by piece, print by print, project by project.

His work — from the LIFE and Magnum years, time on the road, personal projects — lives in his archive. The old work is sorted by year and by project. Sixty years of work reside in black boxes, labeled and stacked on high shelves made of wire. Large prints encased backed with protective foam boards lean at the edges. The almost-square room is climate-controlled (humidity is the enemy of preservation), and its walls are made of cinder blocks filled with sand, then covered in concrete. If there is ever a weather event or fire, Uzzle and his growing collection should be secure.

Uzzle searches through large-scale prints of his photographs. Photo by Megan Dohm

But the most crucial factor when Uzzle considered moving to Wilson was not real estate. It was the work. He was not picking a town by throwing a dart at a map. He was coming back with a mission: To photograph black life in the South, with all the complexity and care the subject requires. He sees a rich world of artistry, tradition, and culture born out of struggle, but too frequently overlooked in the world of fine art. He points to an example from ordinary life, African American church ladies and their fine selection of hats. After seeing similar hats his whole life, watching them bob past on the sidewalk on Sunday mornings, now he documents and shares their beauty.

“This is what I want to photograph, as I get older,” he says decisively. Creating big work in a small town is not his concern.

“You know where art comes from? It doesn’t come from out there, it’s from right in there,” he says, jabbing a finger at the heart. “The older you get, the easier it is, because all of a sudden you start realizing that my art can only be about me knowing who I am. This is the well I have to go down into. What is it I believe? What is it I care about? … What are the values that make sense? What are the issues that I see happening out there that affect me, that I feel something about? And if I do feel something about them, what am I going to do with it?”

Congregation Ladies; Photo by Burk Uzzle

Although he is by nature unflappable, Uzzle is thoroughly irritated by the general state of 2019 America, which sparked this new era of work that is socially conscious. His soul is stirred up, and so is his work.

“So far as being an artist is concerned, I think you should answer only to your own conscience,” he says. “If you — as a mature, thoughtful person that’s lived enough and had enough life experience to have some perspective of quality, of depth — that should be the violin you play.” To satisfy his conscience and interests, the direction of his heart, he often puts his finger on the wounds of racial disparity, looking for reconciliation and a better South. Part of his self-assignment is to photograph and give expression to a known community, his community, the one he has been living in for years.

“Art is the only medium that’s going to work to make the South a better place,” Uzzle says, cautioning me not to misunderstand the qualities of the South that make the subject worth pursuing. “The South understands and values eccentricity. The South understands and values creativity. The South understands and embodies sensuality. The South knows and understands intuitively it is of the earth.”

Uzzle’s studio is largely empty, filled with potential for any setup he can imagine. When I visited, Uzzle had expected a man to come and build a set for a new project. But the carpenter was ill, and Uzzle forgives his absence with a wry smile. A coffin left over from the manufacturing days is propped against the back wall. Any potential set pieces are on wheels, for easy movement. A pulley system hangs from the ceiling, ready to lift, move, and attach lights to wherever the artist pleases.

Uzzle said he rarely works solely with natural light.

“There are no more rules anymore in art. That’s all breaking down,” he says. “Photographers, sculptors, painters, performers. All those rules have completely gone. Any law that says you can only take a picture with a normal lens, or you can’t pose pictures, or you can’t combine pictures and meld them together ... All that’s dead. And I’m happy I’ve lived long enough to see all of those silly rules that were hanging us up, building fences around us. Those rules are gone. And what a nice thing to live in the South with all those rules gone.”

These days, Uzzle creates work that connects his home with its better qualities, while issuing a loving but stern challenge. Each morning, he is up at 4:30, and starts the day with an hour of cycling and thinking, followed by half an hour of yoga. Remembering Capa’s advice that he is only as good as his own two legs and his last picture, Uzzle tries to keep his legs in shape. After a shower and breakfast, he digs in to work. He says there is always something to be done. There are files to craft (often while peering at the computer screen through the bottom of his glasses), pictures to shoot, prints to make, research to do.

“I don’t even think about days off. I don’t want days off. I just want to be able to do my work.” This is not said with the bravado of a younger man. Instead, it is said with the maturity of an older one who understands the task at hand. Between shoots, he takes long drives in every direction, always taking side roads. He says alternating between his closed studio environment and the open road helps keep both fresh.

Photo by megan dohm

In his studio, one can see how his current work methodically explores different aspects of African-American life — sometimes regarding domestic life, artistry, ancestry, culture, and accomplishments, sometimes focused on historic inequities. Although he practices no religion, Uzzle loves church music, and he has met many of his subjects at worship services. Once his subjects arrive at the studio, everyone gets to know each other. He explains his mission, and if the subjects agree with it, they choose to become part of Uzzle’s work.

The results reflect Uzzle himself, but in collaboration: honest, open, precise, and appreciative of beauty and personality.

“People need to learn how to trust each other,” Uzzle says. “And to be more open-minded and more inclusive, and understanding of the value of other people with different colors, different languages. We’re all too stuck in our own mud, so we’ve got to get unstuck. And artists can do this. Politicians are not helping at all.”

In everything, he honors his subject with time and thought.

“I consider my photographs to be little operas. I think of the way I compose and think about, conceptualize. ... My pictures take a long time to do. I think them out.”

Like Puccini’s operas, Uzzle’s photographs must have a libretto, harmonies that rise and fall, dimension and tonality. Even when was shooting candid photos on the fly at Woodstock, he describes his split-second composition process in terms of main and secondary characters. As he navigated the fields strewn with tents, trash, music, and people, he instinctively knew where to look for the clearest and best story.

Sixty years into his career, Uzzle is still looking carefully and listening hard for the leading strains of a melody.

Viewers who can still themselves long enough to listen with him always learn something new about his subjects and the worlds they live in.

Megan Dohm is a writer and photographer living in Raleigh, NC. She was born in Raleigh. She graduated from Thomas Edison State University and holds a degree in history. She has written for NC Coast, Raleigh Magazine, The Bitter Southerner, and her own amusement.