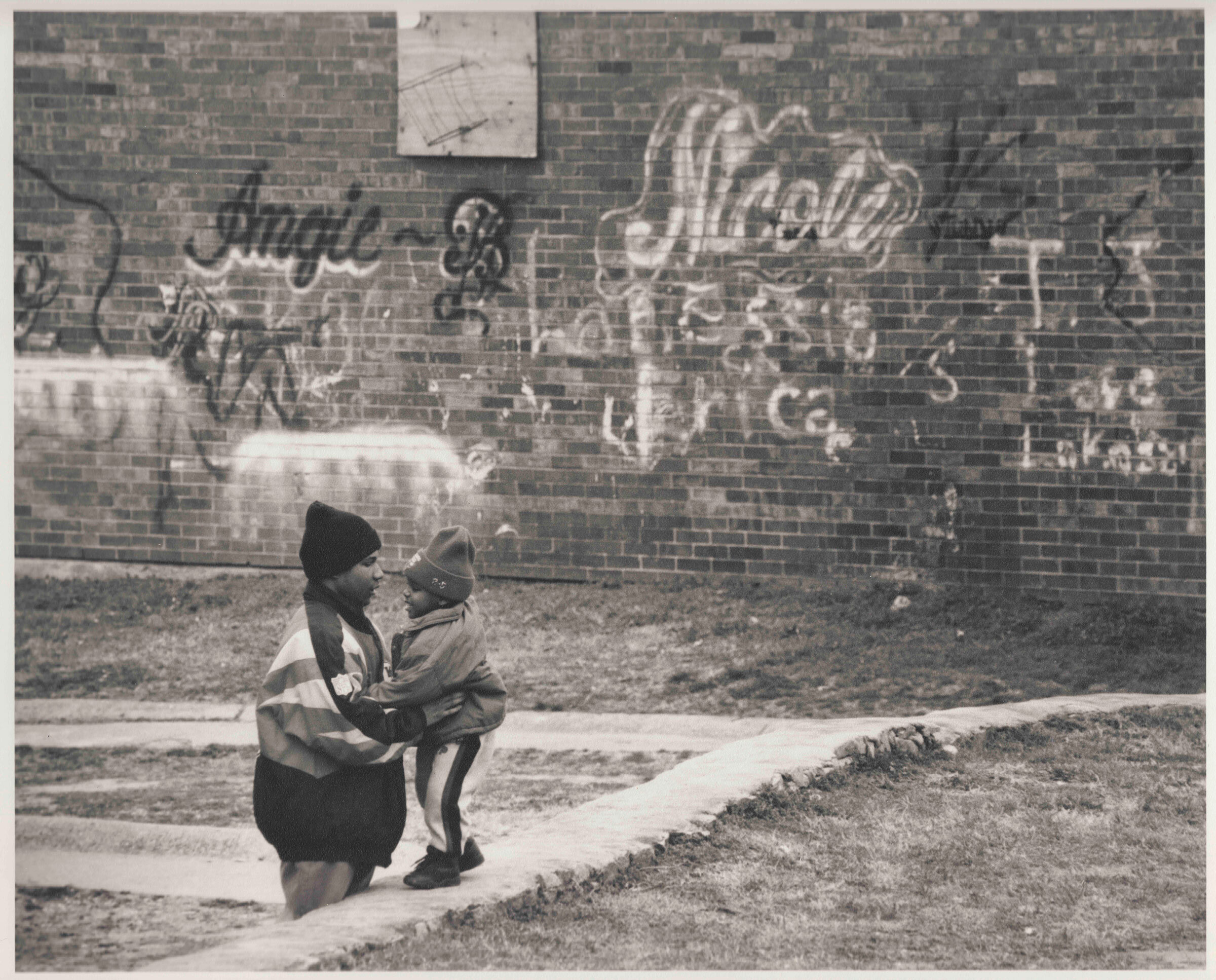

Photo by Tim Huber

A new PBS documentary, premiering on TV tonight, looks hard at one public housing development in the South — Atlanta’s East Lake Meadows — to tell the larger story of public housing in America.

By Max Blau

In the early 1970s, when Lawrence Lightfoot was 14, flames tore through his aunt’s house on the east side of Atlanta, leaving his family with nowhere to stay. One of the few places available was East Lake Meadows, a 650-unit development that was being built by the city’s housing authority. As one of the first families to move there, he saw promise in the pristine low-slung brick apartments and neatly trimmed courtyards.

After a few years, East Lake Meadows started to fall apart due its cheap construction and insufficient upkeep. Lightfoot remembers sewage leaks, roach infestations, and rats. Drugs and violence followed. The overall conditions worsened enough for East Lake Meadows to earn a notorious nickname: “Little Vietnam.” But Lightfoot’s strongest memories weren’t the sounds of police sirens, but the piano in his family’s apartment. His mother had bought the piano from the white family whose house she cleaned, paying for it in installments. One of Lightfoot’s younger brothers, Elgin, was drawn to it. They didn’t have money for lessons or sheet music. So when their neighbor dropped the needle on a vinyl record, Elgin played along. It was how he learned his first song — “I’ll Take You There” by the Staple Singers — and developed a skill that would lead to a music scholarship.

Elgin Lightfoot at the Piano, connie lying on the couch to the left, circa 1973. Photo by Barbara atterberry

“There were birthday parties, children playing in water from opened fire hydrants, because when you can’t get out, you find light in the darkness,” Lightfoot recalls. “The media was not very kind to East Lake Meadows. They didn’t get it all wrong, but they only focused on what was wrong.”

Indeed, many East Lake Meadows residents felt that their full humanity rarely made it into the news. When filmmakers Sarah Burns and David McMahon first came to Atlanta to meet with East Lake Meadows residents, over two decades after the development’s demolition in the late 1990s, they heard a common refrain: Are you also going to talk about the good parts?

“Poverty, crime, and drugs wasn’t the complete experience of people,” Burns said. “They had happy memories, raised families there, and created community bonds.”

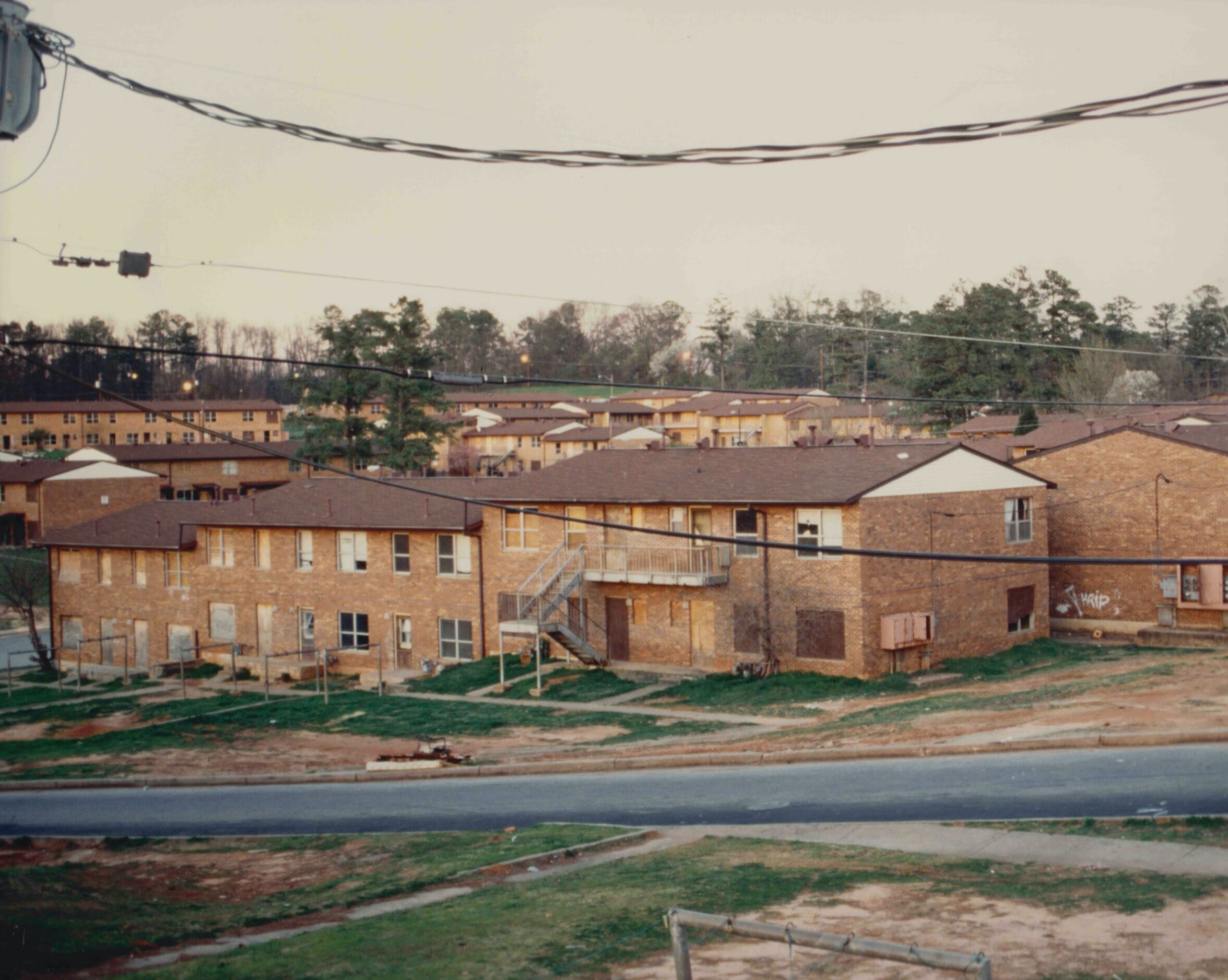

East Lake Meadows, circa 1996. Photo by Tim Huber

Burns and McMahon’s documentary, “East Lake Meadows: A Public Housing Story,” which premieres tonight (March 24 at 8 p.m. EDT) on PBS, achieves a fuller portrait by turning the camera back toward more than a dozen former residents of the since-demolished development. Hearing their stories, Burns — daughter of iconic documentarian Ken Burns (who is the new film’s executive producer) — says she realized Atlanta was the perfect setting to tell a story about America’s public housing. In the 1930s, Atlanta was the first city to build modern public housing units. They were marketed largely to working-class white people, a temporary stop on the way to presumed home ownership. But as lenders approved more loans to white Americans, black families became the face of public housing. Predatory loans and redlining obstructed black families’ pathways.

“[African Americans] weren’t able to buy homes in white neighborhoods across town due to the prevalence of what’s known as restrictive covenants — lines written into the deeds of homes that forbade the purchase or occupancy by non-whites,” Princeton University historian Kevin Kruse, author of 2007’s White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism, says in the film. “So when the Supreme Court strikes down the enforcement of restrictive covenants, essentially rendering them useless, it’s open for African Americans to move into previously white neighborhoods.”

Scenes from the East Lake community. Photos by Tim Huber

White flight dramatically transformed the East Lake neighborhood, where the scorched Lightfoot home sat near one of America’s most prestigious golf courses, established in 1904. At the start of the 1960s, East Lake had approximately 8,000 white residents and nine black residents, who primarily worked for white families, according to Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Douglas Blackmon. By the end of the decade, East Lake had approximately 1,000 white residents and 9,000 black residents. In the film, Blackmon describes the dramatic shift as a “reflection of classic apartheid in an American city.”

“They tried to move as far as they could from us,” Lightfoot said in the film. “They had a lot of places to go. We didn’t have a lot of places to go.”

Just as East Lake Meadows opened in the 1970s, federal officials began to disinvest in those kinds of units, increasingly shifting resources toward Section 8 housing vouchers. Throughout the film, Burns and McMahon show how the national policy shifts — explained by a cast of scholars (Mary Patillo, Lawrence Vale) and journalists (Nikole Hannah-Jones, Jelani Cobb), and officials (former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Henry Cisneros and former Atlanta Housing Authority CEO Renee Glover) — affected families like the Lightfoots. But Burns says it is important not just to portray East Lake Meadows residents as victims of those policies, but also to tell the story of their resiliency.

“The people who lived here were smart, talented, and were looking to make their community better,” Burns says. “They would drive each other to work and create businesses and structures. People built those things out of nothing — and it was amazing.”

~ Watch the Trailer ~

No one exemplified East Lake Meadows’ spirit of ingenuity more than the late Eva Davis, the longtime president of East Lake Meadows’ tenants' association. When police ignored the daily concerns of gang violence, or only showed up on politically-motivated drug raids, she blasted politicians in the press. When the government failed her neighborhood, she demanded improvements to sidewalks and streetlights, organized rent strikes, and gave the community a voice. Though they lacked rights as renters, she accrued enough political capital to force politicians to address their concerns. Her power peaked in the mid-1990s, when Atlanta became one of the first cities to announce it would demolish public housing and replace those units with mixed-income apartment complexes. The redevelopment of East Lake was done in partnership with developer Tom Cousins, who had purchased the historic East Lake Golf Club. East Lake Meadows had been built on the club’s former second course, and the proximity of the two sites meant that golfers swinging their clubs could hear gunshots. Rather than wall off the golf course from the rest of the East Lake Neighborhood, Cousins sought to redevelop the broader area in a way that he felt would improve the quality of conditions for East Lake Meadows residents.

As onetime East Lake Meadows resident Aseelah Muhammad recalled in the film: “Ms. Davis felt like they were trying to steal that land back, and bring the golf course all the way through. They kept trying to tell us, ‘No, that's not going to happen.’ But suspicion was always in the back of everyone's head.”

The documentary shows Davis in motion, speaking out and demanding Cousins and Glover take residents seriously in the redevelopment process. Davis defiantly told a reporter that officials “think we are dumb, and they think we are stupid, erratic, and crazy.” In that same TV interview, she said, “They don't even give the residents of this development credit for having common sense, which we were born with."

Eventually, Davis secured the chance for residents to decide on redevelopment plans. At a tense meeting, East Lake Meadows residents voted it was in their best interest to have their homes demolished and replaced with the Villages at East Lake, a 542-unit development that set aside half of its units for low-income residents. Though residents forced to leave at the time of demolition were promised a chance to return if they wanted to, the housing authority evicted tenants who violated long-unenforced rules in the run-up to the demolition — a move that limited the pool of residents who could return.

An aerial view of the East Lake Meadows housing project, Atlanta, GA, circa 1996 . Photo by Tim Huber

The Villages at East Lake remain to this day. But experts remain split over whether the redevelopment improved the lives of residents. The drugs and violence disappeared with the buildings, but only 69 families of the 423 that called East Lake Meadows home before redevelopment returned to the Villages. The remaining residents — those who left on their own, or received a housing voucher — scattered across the metro region. As Burns notes, Atlanta’s housing authority did not track people very well, which makes it hard to determine the full impact of Atlanta’s grand housing experiment.

“East Lake is a wonderful, upscale neighborhood now, and I’m glad there’s a grocery store, and that the crime is down, and the basketball court has no cracks,” Lightfoot says. “The people I grew up with could never live there now.”

Every year the 66-year-old U.S. Postal Service employee returns for East Lake Day, a celebration of the community that housed his family in their time of need. He also returns to work out at the East Lake YMCA. When he looks around and sees those houses, the charter school, and the revived East Lake Golf Club — home to the PGA Tour Championship — they seem out of place compared to the East Lake he knew. But when he closes his eyes, he still hears the sounds of his old home, from friends singing “Happy Birthday” to his brother on the piano, playing along, as sweet soul music rose from the grooves of a vinyl record.