Katie Mitchell’s groundbreaking new book, Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores, profiles more than 50 Black bookstores — with artwork, photography, poems, essays, histories, and Afrofutures by noted contributors such as Nikki Giovanni, Kiese Laymon, and Pearl Cleage. Though the Atlanta author’s research took her nationwide, it reinforced her conviction that Southern voices are especially critical in this precarious moment of our nation’s history. Here, Mitchell shares her powerful observations about why books chronicling our shared past and speaking truth about the present are imperative. She also provides a reading list of titles she and her bookstore colleagues find most essential right now.

Words by Katie Mitchell

Photo by Lynsey Weatherspoon

July 15, 2025

When writer James Baldwin released his 1982 postmortem of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, a film entitled I Heard It Through the Grapevine, Baldwin lambasted Atlanta for conducting “the most extraordinary, spectacular makeup job in the history of the world.” Walking the streets of “the city too busy to hate,” Baldwin marveled at the gap between the Southern city’s reputation and reality, between the rise of civil rights statues and the fall of civil rights statutes, between the rise of white lies and the fall of Black truth.

“I was wondering,” sighed Baldwin, “what Martin Luther King would have thought of his Atlanta now?” Today, like so many other Atlantans, I echo Baldwin’s dismay amid the continuation of the South’s historical revisionism, amid our ongoing “extraordinary, spectacular makeup job” of reshaping the literal by removing the literary.

In this age of book bans, it’s so strange to be a Southern reader and writer, to live in a county named after Cherokee in a country that’s banning books about the Trail of Tears, to live in the shadow of Stone Mountain carved for Confederate generals in a country banning books about the Civil War, to live in a city where a larger-than-life mural of civil rights icon John Lewis towers over the community, only to watch down over his beloved constituents banned from reading about the Freedom Rides and the sit-ins.

To be a Southerner today is to live in a region anchored by the past in a country outlawing it. It is a project that seems, to us, impossible. It seems as absurd as telling the people of Seattle to ban books about the rain. It seems as ludicrous as telling the people of California to ban books about the ocean and the sun. We who were raised under Confederate flags, who swam in waters named Chattahoochee, do not have the luxury of forgetting, of denying America’s inconvenient truth.

This truth, when bound into books, is what so scares our citizens, is what instills local school board meetings with their manic, caustic atmosphere — hysterical gatherings horrified by reckonings about the roots of American prosperity. For now, whenever a Black woman reflects on the reality of the heel of Jane Crow on her neck, a panic ensues. Administrators change curricula. Librarians purge inventory. Politicians throw the book at people who publish books.

Yelling, lurching, screaming, America’s denialists do whatever they can to continue living in a society built by whips and chains, while believing it is all the result of a Protestant work ethic guided by the Invisible Hand.

All around us, our national psyche is now ravaged by untruths, by lies about vaccines, lies about the police, lies about tap water, lies about the “fake news” — by the Republicans’ “Big Lie” about the 2020 election, by the Democrats’ little lies about the severity of racial resentment and white supremacy. As former president Barack Obama wrote of his truth shading in his most recent memoir, A Promised Land: “I confess that there have been times during the course of writing this book, as I’ve reflected on my presidency and all that’s happened since, when I’ve had to ask myself whether I was too tempered in speaking the truth as I saw it, too cautious in either word or deed, convinced as I was that by appealing to what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature I stood a greater chance of leading us in the direction of the America we’ve been promised.”

A lie is a lie — whether told to harm, or to heal. Here, in Obama’s words one reads a sense that America is so allergic to the truth, so incapable of processing difficult realities about our past and present selves, that perhaps concealing is our only possible form of communication. It is this idea that is so thoroughly dismantled by Southern writers and Southern writing.

The blessing of Southern books, of Southern authors, is that we know our history is inescapable. We are, from an early age, taught to make our peace with hard truths, with all of its tragedy and beauty, with all of its devastation and diversity. And at our very best, our books embody the thorny work of creating an honest pluralism, of colliding and reconciling all our cultures and histories. Like the cuisine of New Orleans or Charleston, Southern literature is bubbling and boundless, stirring the French, the Spanish, the African, the Caribbean, the Native American influences into an uncompromising stew of creative genius.

Southern writers do not pretend that America’s sordid past is popular, they simply write it so well as to make reading about that past popular. This is what great art does, makes the untouchable graspable, renders the unspeakable elegiac. This is true not just of Southern writing, but of all great writing.

In her brilliant new biography Survival Is a Promise, Duke Professor Alexis Pauline Gumbs profiles Audre Lorde, who was a master of this craft. Describing the challenge of communicating across differences, Lorde once wrote, “I am reminded of how difficult and time-consuming it is to have to reinvent the pencil every time you want to send a message.” Yet this is exactly what Lorde did, and it’s exactly what so many Southern authors do time and again. They reinvent form and function to communicate across race, class, region, orientation, and gender. We reinvent genres, reinvent history, reinvent biography, reinvent children’s literature, reinvent fiction and nonfiction to hold all of our truths, and all of our histories.

Right now, as our nation struggles so mightily to get to the bottom of its identity, it’s only right we look to the South. Here is a list of a few of our bravest, boldest, and most brilliant books of this year — writers who, like our greatest Southern traditions, have found a way to embrace the past, present, and future with fearless imagination and ingenuity. ◊

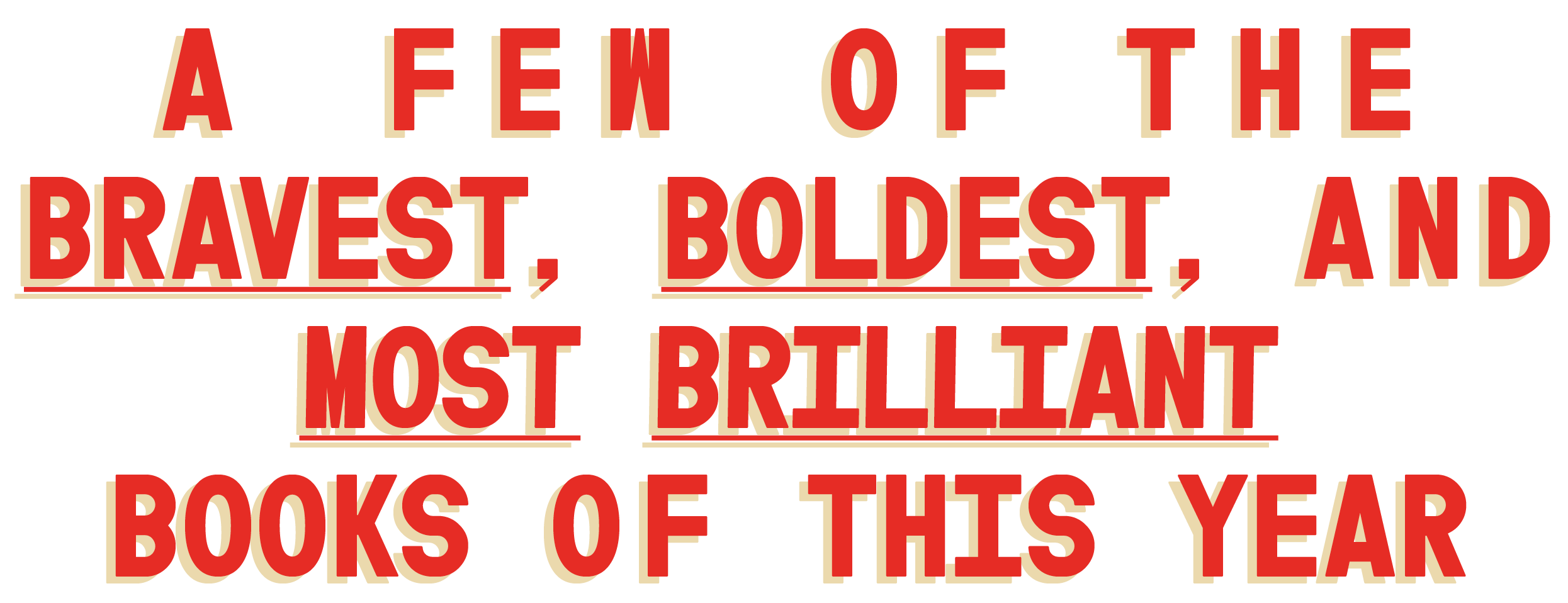

The Message

By Ta-Nehisi Coates

When Between the World and Me was published in 2015, Ta-Nehisi Coates bounded after James Baldwin’s literary legacy, rapidly closing the gap. “I have been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin died,” wrote Toni Morrison of the book. “Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates.” Ten years later, Coates now dashes after the mantle of George Orwell. And yet again, he is up to the task.

Coates’ new book of essays, The Message, began as homage to Orwell’s Politics in the English Language. Like Orwell’s greatest works, The Message explores how authoritarian governments remove, reshape, and manipulate words and history to subdue its populace. Traveling to South Carolina to report on the attacks on Black books in schools, Coates interrogates a country that outlaws slave narratives in classrooms while it enshrines “Klansmen, enslavers, and segregationists” in state capitols.

“The statues and pageantry can fool you,” notes Coates. “They look like symbols of wars long settled and on behalf of men long dead. But their Redemption is not about honoring a past. It’s about killing a future.”

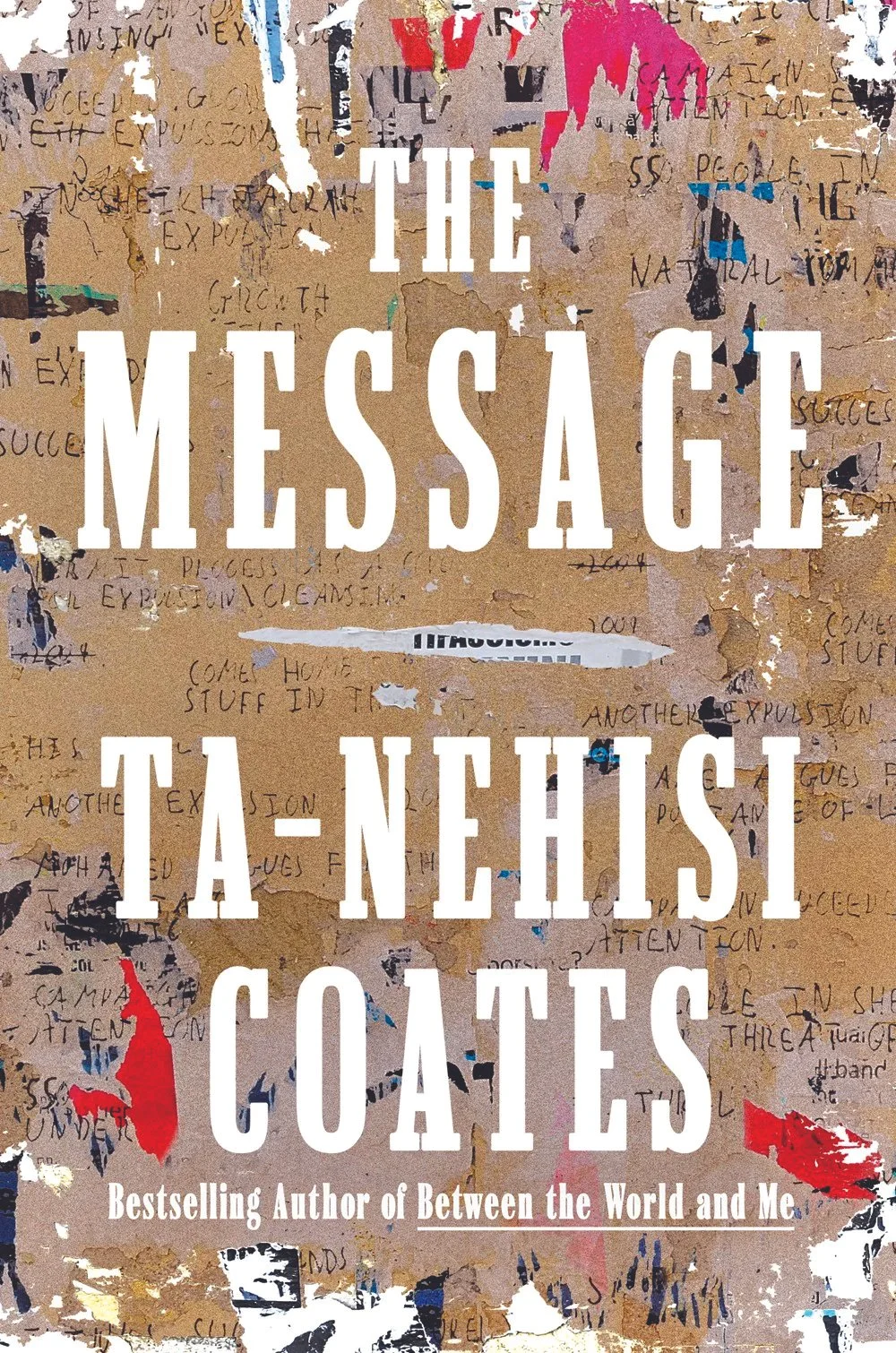

City Summer, Country Summer

By Kiese Laymon | Illustrated by Alexis Franklin

After his hit memoir Heavy, Kiese Laymon wanted to write something lighter. Laymon’s new book, City Summer, Country Summer, is as buoyant as a June bug floating on a midsummer’s night breeze. Celebrating crucial and tender qualities of softness and touch, Laymon casts Black boys in a new light, one rarely seen in literature.

The story of three Black boys spending a magical summer together in the lush natural abundance of Mississippi, the book is an ode to family, safety, and discovery. “I want to create art and read art where Black children are allowed to be lost because being lost is a kind of experimentation,” Laymon told NPR’s Michel Martin of the book.

In City Summer, Country Summer it is we, the readers, who get to lose ourselves in Laymon’s characteristic lyricism, in his everlasting conviction that “Black people deserve beautiful sentences.” Laymon writes: “Whether it was absolute fear or exquisite satisfaction, wandering through those cool spots in those Mississippi woods was too much for New York’s body. We didn’t speak this, New York didn’t speak this, but our bodies knew.”

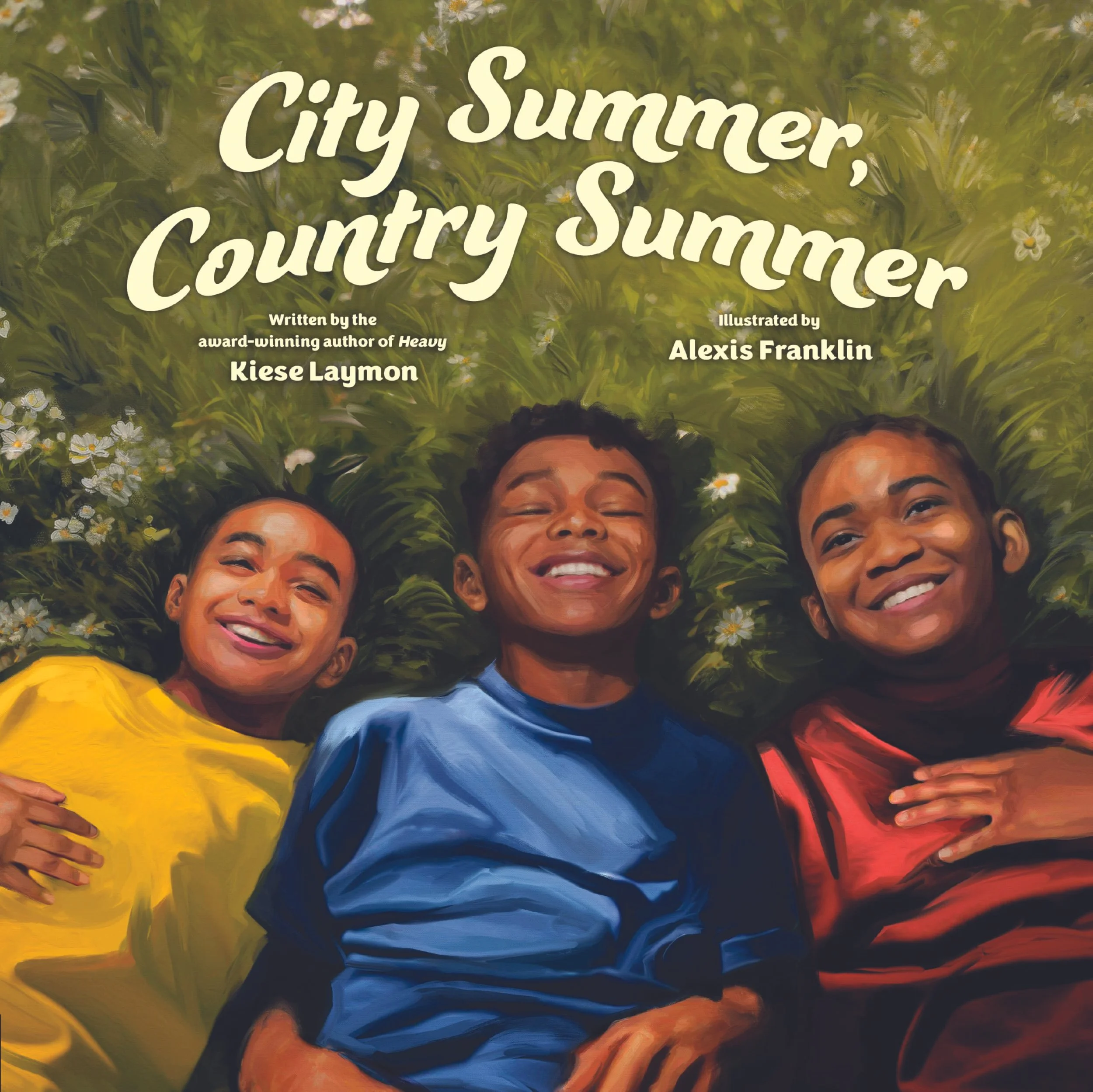

Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People

By Imani Perry

A whole book about one color? The scholar, biographer, professor, and essayist, Imani Perry knows that you might be suspicious of the concept of her new book, Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People. Worry not, dear readers. As Perry reassures you in this new, ravishing work: “You might be thinking by now that this blue thing I’m talking about is mere device, a literary trick to move through historic events. And if blue weren’t a conjure color, that might have been true. But for real, the blue and black is nothing less than truth before trope.”

With truth before trope, Black in Blues uncovers meaning in moments of Black history big and small, building up to a new way to view us, a new framework through which to understand what connects Black people as a people. From Fannie Lou Hamer’s blue dress worn to her 1964 Congressional testimony, to Coretta Scott King’s blue wedding dress, to Louis Armstrong’s 1951 “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black And Blue” to Nina Simone’s “Little Girl Blue,” Perry uses a single color to explore the full spectrum of human emotion. Like so many of the musical geniuses she profiles in this book, Perry’s lyrical prose blasts mesmerizing blue notes articulating the previously imperceptible to Western ears.

— recommended by Loyalty Bookstore, Washington, D.C.

boy maybe

By W.J. Lofton

W. J. Lofton is a rising star in the Atlanta poetry scene. He hosts a writing salon at Auburn Avenue’s For Keeps Books, where lucky scribes glean his literary wisdom in writing circles. But on the pages of his new book, boy maybe, Lofton educates a wider audience about the potent powers of poetry. In poems that “channel the energy, urgency, ambitions, joys, and sorrows of a young Black queer artist,” Lofton covers an astonishing amount of ground exploring race, family, desire, joy, history, and mortality.

With a stunning economy of truth, Lofton renders life’s thorniest moments mesmerizing: “we’d make the dirt move. thunder telephones lightning & buys us a minute with God. prayer feels like rain at first. feels like an ocean being planted & unplanted.”

“I wrote the book that saved my life,” Lofton told ArtsATL. It might just save yours too.

— recommended by yes, please bookhouse & carespace, Scottdale, Georgia

Sky Full of Elephants

By Cebo Campbell

In a world plagued by reboots and remakes, Cebo Campbell’s Sky Full of Elephants offers a shockingly fresh narrative concept: “One day, a cataclysmic event occurs: all of the white people in America walk into the nearest body of water.”

The novel follows a Black Howard University professor, Charlie Brunton, and his biracial daughter, Sidney, a 19-year-old left behind by her white mother and step-family, who are lost to the aquatic rapture. As Charlie and Sidney head south to “the Kingdom of Alabama,” they embark on an odyssey of discovery, connection, and reckoning. Sky Full of Elephants is a heartwarming and hilarious Afrofuturistic allegory with twists and turns rivaling the best of Jordan Peele’s and M. Night Shyamalan’s thrills on the silver screen. Calling to mind the opening of Toni Morrison’s Paradise “They shoot the white girl first … ,” Sky Full of Elephants’s opening lines take off like a rocket: “They killed themselves. All of them. All at once.”

— recommended by Medu Bookstore, Atlanta

Isaac’s Song

By Daniel Black

Reading Daniel Black, author and professor of African American studies at Clark Atlanta University, it’s easy to see why he was a 2024 Georgia Author of the Year Award Winner. “You become an agent of your own existence the minute you stop blaming others for what they did to you,” writes Black. “Those who hurt us cannot heal us. That’s our job.”

And so the wisdom unspools from Black’s new novel Isaac’s Song. A coming-of-age tale chronicling a young queer Black man navigating the turbulent 1980s, Isaac’s Song is a story charting the work it takes to overcome trauma and discover one’s sense of self.

In this inspiring and beautiful story, the protagonist Isaac confronts the legacy of his conservative father, toxic masculinity, and American racism. Under a therapist’s suggestion, Isaac begins to embrace writing and narrating his own story to release his latent creativity. The result is a beautiful work of art that is as therapeutic for the protagonist as it is for the reader.

— recommended by A Small Place Bookshop, Avondale Estates, Georgia

There Is No Place for Us: Working and Homeless in America

By Brian Goldstone

It’s an old political adage, that in democracies there are no famines — because the people will never consent to starve themselves, because voters never vote themselves hungry. But then what of homelessness? Do we, the American people, consent to this? The specter of mass homelessness in the richest nation in the history of the world calls into question whether America’s economy is one that belongs to a democratic society or if it is a hallmark of something darker, something more extractive.

These are the provocations broached by Brian Goldstone’s brilliant new book There Is No Place for Us: Working and Homeless in America. Goldstone’s journalism constructs a masterwork of tragic irony, recounting the lives of laborers who toil in a wealthy land without a place to call home. “The Working Homeless,” notes Goldstone, “the term seems counterintuitive, an oxymoron. In a country where hard work and determination are supposed to lead to success — or at least stability — there is something scandalous about the very concept.”

Reminiscent of The Working Poor: Invisible in America by David K. Shipler, There is No Place for Us profiles five Atlanta families living on the fringes and devastates readers’ hearts. “These families find themselves trapped in a sort of shadow realm,” writes Goldstone, “languishing in their cars, the overcrowded apartments of friends and relatives, and hyperexploitative extended-stay hotels and rooming houses.”

A must-read for all conscientious citizens.

A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUs

By Crystal R. Sanders

The debt to public HBCUs is so large it is indeed hard to fathom. According to a 2023 accounting by the Joe Biden White House, over $13 billion has been stolen from land-grant HBCUs in the last 30 years alone. The modern case for reparations is strong indeed, but the historic case is perhaps stronger.

A new book deepens our understanding of this ledger. In A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUs, Associate Professor of African American Studies at Emory University Crystal R. Sanders explores the jaw-dropping history of “segregation scholarships” provided by Southern states to Black students seeking graduate education before the Brown v. Board of Education decision. In what unspools like a stunning exposé, Sanders illuminates how segregationist states stole money from HBCU budgets to ship Black students out of the South instead of integrating white colleges or investing in Black colleges.

Tracking billions bilked, Sanders reveals that missing funds, not mismanagement are to blame for HBCUs’ economic struggles.

“We often see these institutions as struggling financially without understanding why they’re struggling financially, and all too often, it’s written off as poor leadership or poor governance,” Sanders said at Vanderbilt Law School. “This is not an issue of governance, [rather], it is an issue of systemic underfunding.”

Our South: Black Food Through My Lens — A Cookbook

By Ashleigh Shanti

One of the most valuable concepts of Ashleigh Shanti’s new cookbook is its disintegration of the monolithic South. Our South: Black Food Through My Lens deepens readers’ comprehension of Black influence on foodways and cultures by exploring five of the South’s microregions, “each with its own distinct flora and fauna, dialects, traditions, and dishes.” With gorgeous photography and design, Shanti whisks us across the mountainous Backcountry, the coastal Lowcountry, the fruit-filled Midlands, the Lowlands, and the Homeland. A geographical romp filled with delicious recipes and cultural discovery, Our South serves up a feast for the senses, leaving readers salivating for more.

With prose that keeps pace with the beauty of this book, Our South delightfully expands minds and appetites. “While I’m fully committed to filling your head with thoughts of buttered cornbread still hot from the cast-iron pan; crunchy, juicy lard-fried chicken ready to be torn into; and luscious, sweet shortcake that’s as much of a feast for your eyes as for your palate — that’s not the beginning and end of this story,” writes Shanti. “In between, I’m out to prove something.”

Our South proves the South is so much more dynamic and delicious than many realized.

— recommended by BEM books & more, Brooklyn, New York

Love & Whiskey: The Remarkable True Story of Jack Daniel, His Master Distiller Nearest Green, and the Improbable Rise of Uncle Nearest

By Fawn Weaver

A fascinating history set in Lynchburg, Tennessee, Love & Whiskey: The Remarkable True Story of Jack Daniel, His Master Distiller Nearest Green, and the Improbable Rise of Uncle Nearest doesn’t just set the record straight but expands it in miraculous ways. Truth is, Jack Daniel didn’t invent the method for distilling Jack Daniel’s Tennessee whiskey. Rather, a formerly enslaved man named Nearest Green did. In Love & Whiskey, author and entrepreneur Fawn Weaver recounts this relationship, as well as her own enterprising efforts to memorialize Nearest Green’s legacy with the founding of her smash hit whiskey brand Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey — now worth more than $1 billion.

Joining the long-running theme of Black innovators written out of historical achievements, this tale places Black Americans’ enterprising spirit in the story of American spirits. The perfect reading companion for a nightcap, Love & Whiskey warms your heart and your stomach.

— recommended by Malik Books, Los Angeles

The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America

By Aaron Robertson

Sometimes Black studies can feel like it’s the study of oppression, of mass incarceration, of police brutality, of extrajudicial killings, segregation, and discrimination. But Aaron Robertson’s new book reminds readers that there is freedom in the Freedom Struggle.

The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America is a new book that looks beyond Black Americans’ attempt at resistance against a recalcitrant society, towards their efforts to build a new Beloved Community. Recounting the stories of the Shrine of the Black Madonna, a Black congregation within the nationwide liberation movement known as Black Christian Nationalism, The Black Utopians investigates how these Black communities “opened bookstores and co-ops, created a self-defense force, and raised their children communally, eventually working to establish the country’s largest Black-owned farm, where attempts to create an earthly paradise for Black people continue today.”

A much-needed tonic for our pessimistic politics today, Robinson’s brave and imaginative book asks readers, “What does utopia look like in Black?”

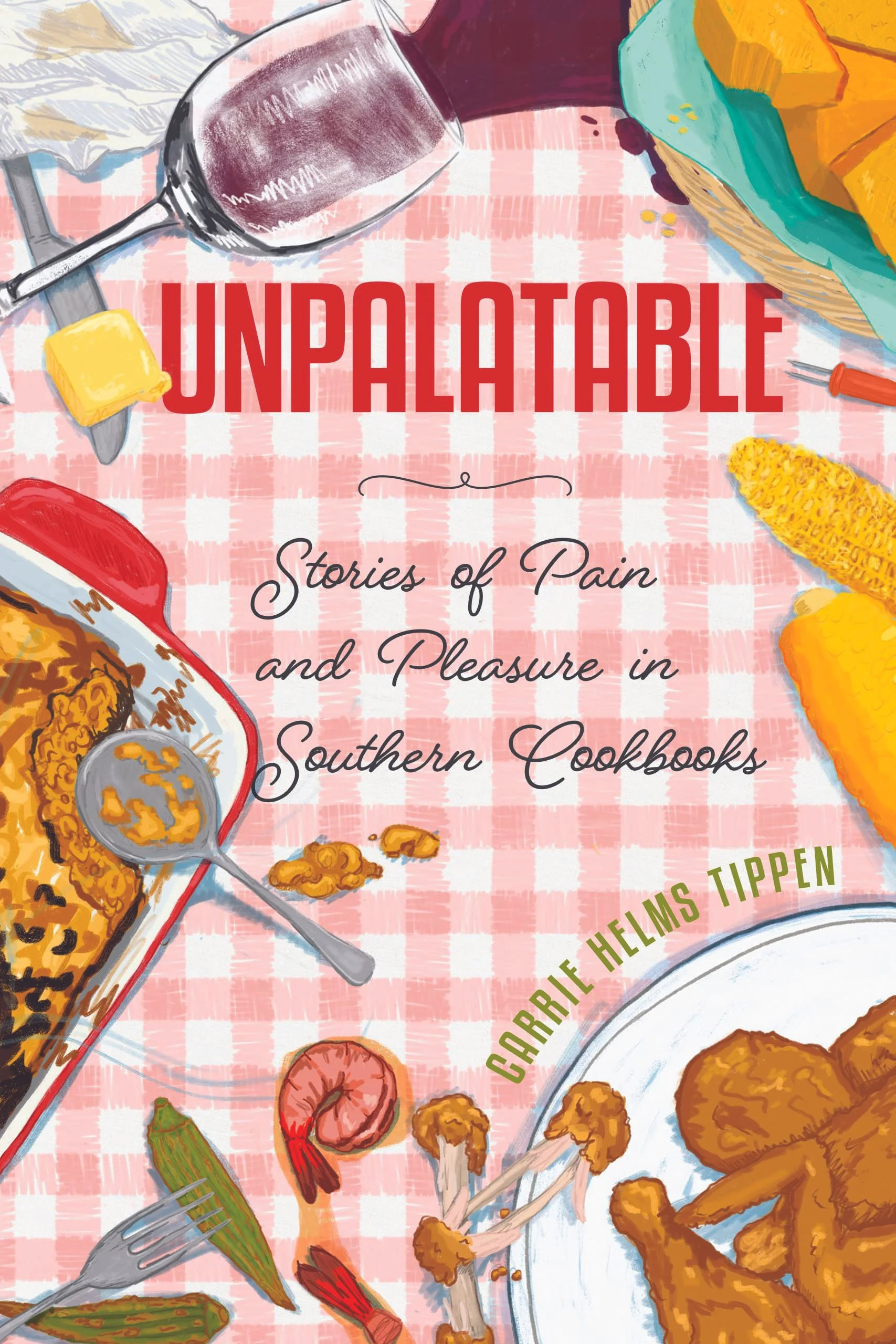

Unpalatable: Stories of Pain and Pleasure in Southern Cookbooks

By Carrie Helms Tippen

The National Museum of African American History and Culture notes that for slaves in the American South, their very being was consumed on dinner tables. “Their lives were embedded in every coin that changed hands, each spoonful of sugar stirred into a cup of tea, each puff of a pipe, and every bite of rice,” the museum notes. The notion of human lives embedded in bites of rice and sips of tea fundamentally changes one’s relationship with food forever. And this uncomfortable, inconvenient truth — the reality that agriculture, food products, and Southern sites of so many culinary monuments double as sites of torture and heartache — are what sit at the heart of the brilliant new book Unpalatable: Stories of Pain and Pleasure in Southern Cookbooks by Associate Professor of English at Chatham University Carrie Helms Tippen.

Tippen digs past the cookbook genre’s conventional “orientation toward celebration and success.” As the publisher notes: “From glossy photographs to heartwarming stories and adjective-rich ingredient lists, the cookbook tradition primes readers for pleasure. Yet the overarching narrative of the region is often one of pain, loss, privation, exploitation, poverty, and suffering of various kinds.” Unpalatable reminds readers of the devastation behind so many foodie delights and explores the full political range of Southern cookbooks, from the escapists to the confrontational. Unpalatable serves up excellent food for thought.

Katie Mitchell is the author of Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores. She’s from Atlanta with familial roots in Jackson, Mississippi.

Lynsey Weatherspoon is a portrait and editorial photographer based in both Atlanta and Birmingham. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, USA Today, NPR, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Time, and other publications. Her work has been exhibited at The African American Museum in Philadelphia and Photoville NYC. She is an awardee of The Lit List, 2018. Her affiliations include Diversify Photo, Authority Collective, and Women Photograph.