August 19, 2025

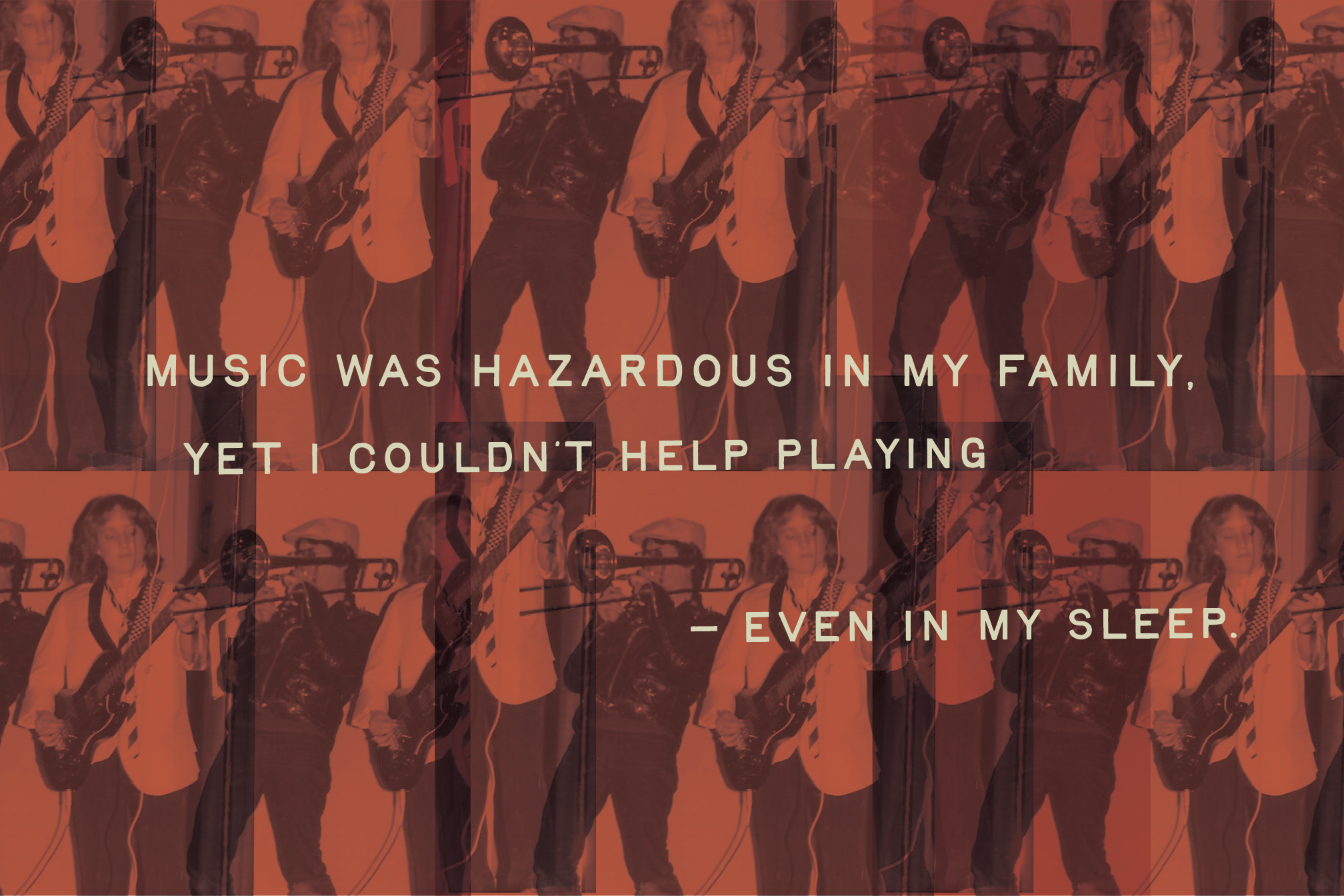

In the 1950s, my paternal grandmother began to lose her hearing. She was late in midlife by then, and by the time she reached her 70s it was almost gone, reduced to shrill, high-pitched whistles and hums borne of disintegrating aural bones. A walnut baby grand Knabe — her prized possession, bought for her by my grandfather at the height of the Depression after she returned from a three-year abandonment of the household — sat gathering dust in the corner of their Brooklyn living room near the radiator, its soundboard cracking in the dry apartment heat. The piano could no longer be tuned, and although she could still play the Chopin that brought her to the stage of Town Hall as a 14-year-old prodigy, it sounded flat and tortured. But my grandmother could no longer hear it; she could only feel the vibration of the wood, the felted hammers, the pedals that could no longer be pressed. Her playing had been reduced to a memory, but her desire to play did not wane: Shortly before she died at 93, she dozed next to me in the backseat of my father’s Toyota while we were on our way to a family function, her eyes closed, hands spread wide on her lap as if on her piano’s yellowing ivory keys, muscle memory taking her fingers through the Nocturne Opus 9 that she knew in her sleep.

I was on my 17th guitar when she died — a little Martin 0-18 bought furtively with money that should have gone toward my rent, and that put me behind by a month, necessitating a secret dip into funds that were not meant to be touched until I married. It was 1990 and I was in my 20s, with another Martin — a big, woody-sounding D-35 dreadnought meant to break through a wall of bluegrass instruments, that had been a gift from my father on the occasion of my 21st birthday — sitting in its case in my tiny East Side walkup Manhattan apartment. On any average weeknight, I came home from my job, dropped my bag and took off my coat, fed the cats, opened both cases, and went from one to the other: the small-bodied, sweet sounding 18, and the booming rosewood 35, playing for hours every night while I waited for my roommate to get home from work. My nightly ritual: open a bottle of white wine, tune the guitars, play, sip, repeat, return the instruments to their cases when my fingerpicking slowed to a drag by the effects of cheap Soave, my playing collapsing into a muddy, atonal clatter.

You play in your sleep, my roommate told me one morning, after we began to share a bed. Your fingers keep moving, even when your eyes are closed. You played Nanci Griffith last night, I could tell.

I looked at my right hand and thought of my grandmother in my father’s car, my thumb plucking an invisible low string, my first two fingers playing the high opening notes of “Once in a Very Blue Moon.” As a child 22 years earlier, I had taught myself to play like this so that I wouldn’t have to sing for a song to be recognized. It was a style crafted of fear, and of playing alone in my 1970s pink shag-rugged Queens bedroom. I would never compete with my former television singer mother, who was possessed of a voice loud enough to shake the windows and rattle the walls. Like my grandmother, who I believe abandoned her family for music on what might have been an otherwise normal afternoon in 1926, my mother, who had been branded “The Next Judy Garland” by her record company, rued the day she was forced to make a decision: get married and raise a family, or go on tour. When she made her choice and stepped off the ABC television soundstage for good after a 13-week season, she would not be anxious to have the daughter she would bear become a musician a few years later. So I learned to play guitar privately and quietly, and wordlessly; I would not sing because I did not want to be disruptive. I did not want to contribute to the sorrow that seemed a part of her DNA, like her height, or the color of her eyes. I wanted her love, unencumbered by the question of who, in our home, owned the music.

From the vantage point of half a century, I look down into this scene as if peering into a diorama. I am a child. My beautiful mother’s creative grief is terrifying and all-consuming, and manifests in a silent rage. It becomes an emetic, a nauseant, whenever my father — in front of extended family and friends — implores me as a child to sing like my mother. I can’t, and won’t: It is a gamble, a risk that I will never take.

My mother and her mother-in-law hated each other from the first time they met, but this was the one thing they had in common: music had, and music lost.

I clung to it, though, as if it were a lifeline, and was obsessed not only by it, but by its conduit — the inanimate wooden objects, sweet as David’s lyre, that held the power to protect me and organize my terrors, to transport me to other times and places, to soften the sting that came with knowing, long before I had words for it, that I was a source of contention for the woman who gave me breath. My grandmother stood on stage alongside a Steinway grand piano as a young teenager in the early days of World War I; my mother sang on the radio when she was 3. Unlike them, the stage terrified me; I wanted the prowess and the skill to play well, but more than anything else I yearned for the instruments as though they were living containers of possibility and promise without the danger of maternal retribution. I longed for guitars in a way that was obsessive, demanding of my focus, addictive like the chase for a better high: one would never be enough.

1983, no-name nylon string, purchased in England where I was studying at the time

In her sleep, my grandmother played Chopin Nocturnes on her lap, her right foot pressing a ghost pedal to control the volume that she could no longer hear when she was awake; while I slept, my fingerpicking was perfect and smooth and unencumbered by a lifetime of reticence. In the earliest of my guitar dreams, I saw myself bent down on one knee, opening the rusting metal latches on a beaten brown leather chipboard case to reveal a dusty tobacco sunburst 1930s Gibson, its finish crazed like fine porcelain. I coughed in my sleep as a cloud of stale Gibson Kalamazoo factory air wrapped itself around me. I was not yet 13, and while my friends were listening to ABBA and Donna Summer, I came home from school every day and spun vintage Carter Family 78s that my father brought home for me, pressed at a time when Gibson cranked out cheap acoustics like the one I dreamt of to soothe Depression-weary Americans who spent every Saturday night in front of the radio listening to Mother Maybelle scratch on her archtop Gibson L-5.

When my father came home one night with a vinyl copy of Farewell, Angelina, my dreams turned to small-bodied guitars laden with pearl, and in my sleep I cradled Joan Baez’s little 1929 Martin 0-45 in my hands like a newborn. When he brought home Norman Blake’s Whiskey Before Breakfast, I dreamt of the 1934 Martin D-18H that I’d read Blake had unearthed in a Georgia farmhouse. I could feel and see it as I slept, its big, slope-shouldered body propped on my lap while I tuned its ancient, dead strings. I told my father about this vision, and on a long car trip to Florida right after the divorce we stopped at every barn sale from Hiawassee to Waycross looking for another one, as though a guitar’s magic had little to do with the skill of its player; I believed that it could be bought for a price and that an identical Martin was out there waiting for me — even though only four of them had been made in 1934, the year before my mother was born, and the year my grandmother’s piano arrived in her Brooklyn apartment after she agreed to come home.

When we arrived in Vero Beach, my father and I sat together eating deep-fried coconut shrimp at a kitschy seaside bar in what had once been his officer’s club during the War, looking out over the water at the shipwreck that he had used for bombing runs when he was a 19-year-old Naval ensign. I was 15 and drinking cold beer and he, gin, and we ruminated on the instruments I longed for, and why. Each one, I told him, had a life and personality all its own; each had the power to make me better than I was, and better than I might ever be without it. I did not like boys and did not yet admit that I liked girls, and guitars were an inanimate repository for my affection. Living with my grandmother in his childhood home with her disintegrating baby grand in the corner of the living room, my father, single after 16 years of marriage, talked openly about what he looked for in a woman, and I talked about what I looked for in an instrument.

Smoothness, sweetness, warmth, a history, an easy and kind neck, playability, I told him, drinking my beer.

Same, he said, sipping his martini, pointing out to the shipwreck.

• • •

An obsession:

I fall in love with the stories that guitars carry in their rattling braces, their chipped bindings, their bent tuning pegs. By my late teens, I can tell the difference between a 1953 and a 1954 Gibson Gold Top Les Paul from 10 paces; I know what makes a Martin 00021 a 21 and not a 28. I know why Gibson Banner acoustics — made solely by women during World War II when the men were off fighting — are different guitar to guitar and why, when the men returned to the assembly line from places like Monte Cassino and Anzio, they took over from the women and fashioned the necks on those instruments to be thick and unsuitable for the smaller, delicate hands of their wives, who were expected to make babies and not guitars.

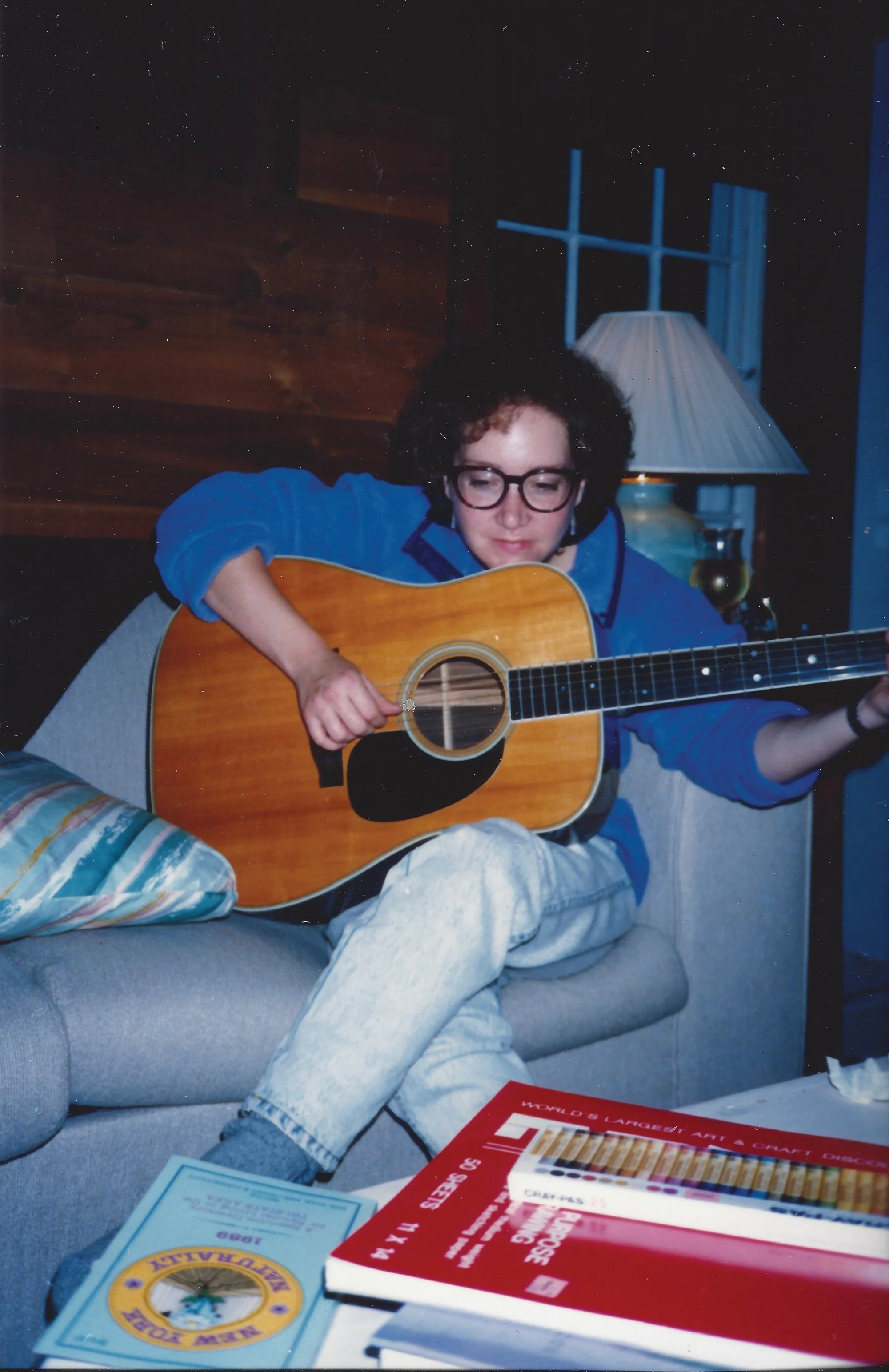

1988, Martin HD-35, at a cottage in Woodstock, New York

Like those baseball bat-necked Gibsons, the Kent nylon string acoustic guitar that I first played at 4 years old was clunky and impossible for my child hands to manage; it had been my father’s before I was born, purchased by him at the Music Inn in Greenwich Village along with a set of bongo drums when he was a Manhattan bachelor during the height of the 1950s beatnik era. He learned how to play three chords — A minor, E minor, and D minor — after his best Navy friend told him that women were turned on by dour music. I can still feel that guitar’s rough, cheaply finished mahogany neck in my hands, and when I stepped on it during one of my parents’ cocktail parties when I was 5 — my small, sneakered foot went straight through its fake spruce top and out its laminated back — I wept unconsolably, as though I had killed my father’s history itself and siphoned the music from it with my clumsiness.

He was not angry with me, and he replaced the Kent with a cheap Spanish classical, a Spanada, that he allowed me to pick out one weekend afternoon at Schirmer’s Music in Manhattan while we waited for my mother to have her hair done in a Beatle cut at Vidal Sassoon, a few blocks away. When she emerged from the salon, I could not contain my delight in having chosen a new instrument of my own for the first time, selecting it from a rack of 20 other guitars. She nodded at the case but said nothing, and gave her hair a quick flip. Together, we walked to the garage where my father had parked our car, a dark green Chrysler Imperial she set fire to a few months later in a 3 a.m. car ride home from Miami, while the radio played Johnny Cash singing “A Boy Named Sue.” When black smoke began to pour from the ashtray in the passengerside door where my mother had stubbed out an entire pack of smoldering Virginia Slims, my father swerved onto the macadam shoulder outside Gold Rock, North Carolina. My mother and I sat in the dark on the side of the road with our miniature Schnauzer, watching while my father beat at the flames with a dirty handkerchief; when they showed no signs of dying, he used the hem of his blue terrycloth shirt to pop the metal trunk latch and grab the Spanada, which had somehow survived the flames and the heat. I do not recall any suitcases — just the guitar, whose finish had melted off its cedar top but was otherwise unharmed, and I continued to play it for another five years. It smelled like smoke and melting vinyl, a synesthetic reminder of our near doom at the hands of my mother’s recklessness, and at every party where my father implored me to take it out and give the guests a song-without-words, someone always asked if anything was on fire.

1987, playing a Martin 0-18 in Manhattan

On a sunny Friday afternoon in May 1971, a month before my eighth birthday and while my mother was visiting with a friend before my father got home from work, I was nearly killed after riding my Apollo bicycle down a long hill into a stone wall across the street from our apartment; my skull was fractured and my eyes blackened and sealed shut until late August. I remember nothing but an agonizing headache following the accident, and not being able to see for months. When my father came home from work with a gift for me — a red and black sunburst Harmony Bobkat electric along with a small Vox amplifier tied across its middle with a red ribbon — all I could do was place my hands on it, its solid body, its curves, its metal pickups, and locate the jack for the cord to the amplifier.

A photograph taken of me four years later at my grade-school dance in 1975 shows me wearing a woman’s hand-painted outfit purchased for the occasion by my mother, which necessitated the maxi skirt being hemmed a full 14 inches. In the picture, I am 12; I am standing in the middle of the school gymnasium surrounded by my gaping classmates, the guitar hanging across my shoulders, my face blurred by shame: I am playing the Creedence version of “Proud Mary,” mumbling quietly in John Fogerty’s accent without a microphone as I strum, wide-eyed and stock still, praying for the Rapture to swallow me up.

1975, Harmony Bobkat, grade school graduation, Queens

That was the year when my grandmother’s piano began to fall apart, and as her piano collapsed, my guitars began to spawn, as if the death of one begat the lives of others: There was a massive Alvarez 12-string — my father believed that more strings were better — and then, a Hofner Beatle bass that he and his best friend, an alcoholic magician named Joel, found while walking around the Belmont Park Racetrack flea market which took place every weekend and sold everything from machetes to bags of striped tube socks. I did not yet play bass guitar, which implies the existence of a band, but my father paid $65 cash for it, and he and Joel brought it home to our apartment, laid it out across our dining room table like a surgical patient, and Joel, with a cigarette dangling from his lips, turned the tuning pegs until the strings, thick as the transatlantic cable, exploded off the body and the trapeze bridge fell off. I wept not from sentimentality — I had not yet made the instrument’s acquaintance and had no emotional attachment to it — but because they had been so cavalier with it before I’d even had a chance to hear it, and to know its story.

A Yamaha classical replaced the melted Spanada in 1977, and in 1978, an orange and yellow sunburst Gibson Les Paul Deluxe replaced the Bobkat; it matched the striped lucite Ludwig drumkit belonging to my friend Ira, with whom I had a regular rehearsal date in his basement, but I gave it up a year later when its weight prevented me from standing up and playing it at the same time. An osteopath adjusted my neck and shoulders and suggested that we sell the Les Paul because it would, he said to my father, take your daughter down and injure her forever. I didn’t miss it when we got rid of it; it had been the misguided manifestation of an altered pubescent reality and the belief that perhaps I could be someone I wasn’t if only I played the right guitar. When I said goodbye to it and my father walked out of the house with its long rectangular case, my mother looked on, poured herself a goblet of wine, put on Peggy Lee and sang along with “Is That All There Is?”

Their marriage began to fail at the same time the Les Paul did, and the guitar was replaced with a hollow body burgundy red Gretsch Chet Atkins just like the one George Harrison played in the earliest days of the Beatles. When my father and I brought it home, I began listening to nothing but Meet the Beatles, learning George’s runs and licks and every flourish in every song while my parents, in the next room, fought over accusations of infidelity, of community property, and who was leaving whom and when and where, and with whom I would live. I heard my father say Arkansas — that a cousin who lived there asked that I be given to her as a mother’s helper, the way one might be given a chair, or a dress — and I unplugged my amplifier from the socket behind the bar in our foyer where my parents kept cheap bottles of export rum and sweet sacramental wine, carried it and the Gretsch back to my bedroom, closed the door and locked it.

2002, Gibson F-50

I imagined it: packing myself up and fleeing in the middle of the night to escape having my future decided for me, of leaving of my own accord in the way my grandmother had left behind her children and husband, and the way I knew my mother wanted to — for music and the possibility of saving herself. Is this what unfulfilled art-making does to the soul? Makes it wild with grief? Did it make them run, make them search for fulfillment elsewhere? My grandmother, years after her return, developed a gambling addiction; my mother, a shopping addiction. Unable to satisfy their musical needs, they turned their desires elsewhere.

The night I heard my father mention Arkansas, I considered which guitar I might take with me if I left — the Gretsch, the Bobkat gathering dust in the back of my closet, the Alvarez 12-string — but there was none that I loved more than another until a few months later, when we traded in the Gretsch for a used Guild D-35 from the late 1960s, its plain, unadorned spruce top aged a deep pumpkin, its neck narrow and flat and perfect for my small hands. For the next year, I sat alone in my bedroom every day after school listening to Appalachian string band music from the early 1900s, my Guild in my lap: I played along with ancient songs about mothers who leave, about poverty and loss, tuberculosis, childhood accidents and house fires, and coal mines and ghosts returning from the dead to haunt cheating spouses, and I snuck little glasses of my parents’ sweet wine into my bedroom until a haze clouded my eyes and my fingerpicking slowed to a crawl, and I could not, would not keep on the sunny side, no matter how insistent Maybelle Carter was that I do.

In the weeks before my father moved out, we sat at our kitchen table, the three of us, and my father brought up the issue of guitars while my mother watched “Name That Tune” over dinners of frozen fish sticks and Hungry-Man fried chicken. He had declared bankruptcy a year earlier and would be forced to live with his mother in Brooklyn, as he had done after the War. But he wanted to know, in the way that young men talk about cars, or women: If you could have any guitar, what would it be? A Martin D-45, dripping with pearl inlay? An Ovation Custom performance guitar, with a round fiberglass back, heavily ornate and meant for the stage? A big jet black Gibson SJ200 like the one that Emmylou Harris played, with a rose spray painted beneath its bridge on the lower bout?

The Ovation, I said — I still do not know why: I was a purist and did not like fiberglass guitars, but Dewey Bunnell of America played one, and I dreamt of leaving Queens for Ventura Highway — and my father made a special note of it on a small pad he kept in his shirt pocket. We discussed it for weeks at every meal — What gauge strings would I use? Would a metal capo scratch the neck? What about my amplifier? — and on the Saturday morning of the day we were meant to drive into the city to pick it up, he lit a breakfast cigarette, took a sip of his Sanka, and said: No. Your mother says No. You don’t need it.

• • •

There have been 24 in all. After the Guild D-35 came another bass, a handmade dreadnaught, a cheap classical I bought in England in 1983; another Guild; an Ovation Classical electric; the Martin D-35; the 0-18; an unplayable 1888 parlor guitar I brought home from a store in Berkeley, California; a Gibson L-50 from the 1930s; a Martin 00-18; a Blueridge dreadnaught that had belonged to my Arkansas cousin’s son, who took his own life; a cheap jazz guitar found in a pawn shop in Maine; a Yamaha steel string bought the same day; a Larrivée parlor guitar that I bought in Nashville; a Martin 000-28 from a famous store in Lansing, Michigan. Although months can go by when I don’t play any of them — I have five of them now — I want more in the way that an alcoholic can’t stop after one glass: I want a 1957 Gibson J-185, Martins from the 1930s, a National Triolian, an Epiphone Casino like John Lennon’s, a Rickenbacker 365 12-string from the 1960s, an Olson, a Greven, a blonde Telecaster with a maple neck, from, specifically, 1967. Mine is a disease of indigence, of yearning and dream fulfillment; like all addictions, it is an attempt to fill a hole, to quench a thirst, to soften sorrow. I have spent my life looking for the one guitar that would change everything, that would change my story, and change the stories of my mother and my grandmother, and would fix them.

My mother, at 89, rehearses every month for a performance that will never take place, paying money she doesn’t have to a retired accompanist who makes house calls, who promises that the stage is still waiting for her.

When I sat in the backseat of my father’s Toyota with my grandmother while she played an imaginary Chopin Nocturnes Opus 9 in her sleep, I did not know that that afternoon would be the last time she would ever lay hands on a piano. A newly married young couple, distant family, had bought a gleaming black ebony upright Mason & Hamlin that no one knew how to play. They wanted to show it to my grandmother and when she sat down on the seat, both hearing aids whistling, she held her right hand up to its front, directly above the keys, played middle C a few times with her left index finger, waited for the wood to vibrate, and without hearing a sound, declared it, correctly, in need of a tuning.

She died at home in her sleep weeks later; her Knabe would be packed up and shipped down to a cousin in Virginia for her daughter who was just beginning to play. It was stripped of its veneer and rebuilt from the inside out for it to be playable again, but when I leaned into its case and breathed, I smelled the essence of time and art, and a thousand dinners prepared by my grandmother in her apartment after she returned home for good, relinquishing her music forever. Like every guitar I owned, or will own, or wanted to own, my grandmother’s piano would not ever be separated from its story. ◊

Elissa Altman is an award-winning author of literary memoir, essay, and food narrative. She launched her James Beard Award-winning narrative food blog, Poor Man’s Feast, in 2008. Her books include Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking; Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw; and Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing.