Story By Katherine Jentleson | Photos by Gregory K. Day

Art by Nellie Mae Rowe

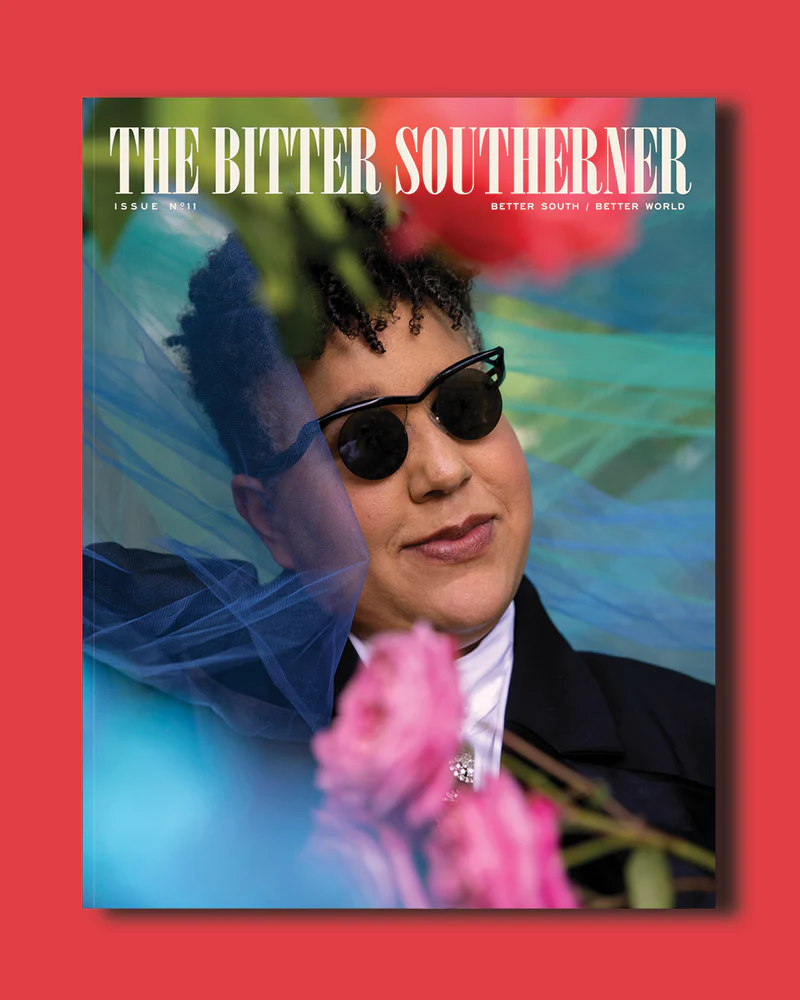

Cross country quest or wild goose chase? The High Museum’s Katie Jentleson takes us takes us along on a curator’s adventure.

August 12, 2025

On a pleasantly warm Saturday in early April 2024, I am standing in a courtyard of blooming cacti, taking deep breaths as I prepare to find out if Gregory K. Day is the real deal.

After several years of getting to know Greg long distance, I’ve traveled thousands of miles from my home in Decatur, Georgia, to his in Palm Springs, California, in hopes of adding to the High Museum of Art’s world-renowned collection of folk and self-taught art. Trembling slightly upon the threshold of a relative stranger is actually not that unusual in my line of work as a curator. I’ve faced some heart-pounding situations. Pulling into a near-empty parking lot of an unmarked warehouse. Being picked up by a driver at LAX and transported to an undisclosed location with no cell service. Once, after wandering through a drafty farmhouse filled with art of dubious authenticity, I was led to an open well. We are big 20/20 consumers in my household (Pat LaLama superfan, here), so the precarity of these situations is not lost on me. I do not want to end up at the bottom of a well.

But art has to be viewed in person, and most people aren’t psychopaths. Though I have faith that Greg is in the majority, I am still a bit skeptical about the too-good-to-be-true quality of his collection: Over decades, but mostly in the 1970s, Greg amassed an array of sweetgrass baskets, nearly two dozen extraordinary quilts made by Black Southern women, and a trove of extremely rare work by the legendary Atlanta artist Nellie Mae Rowe.

Rowe “airing” her quilts, two of which were recently acquired by the High Museum of Art.

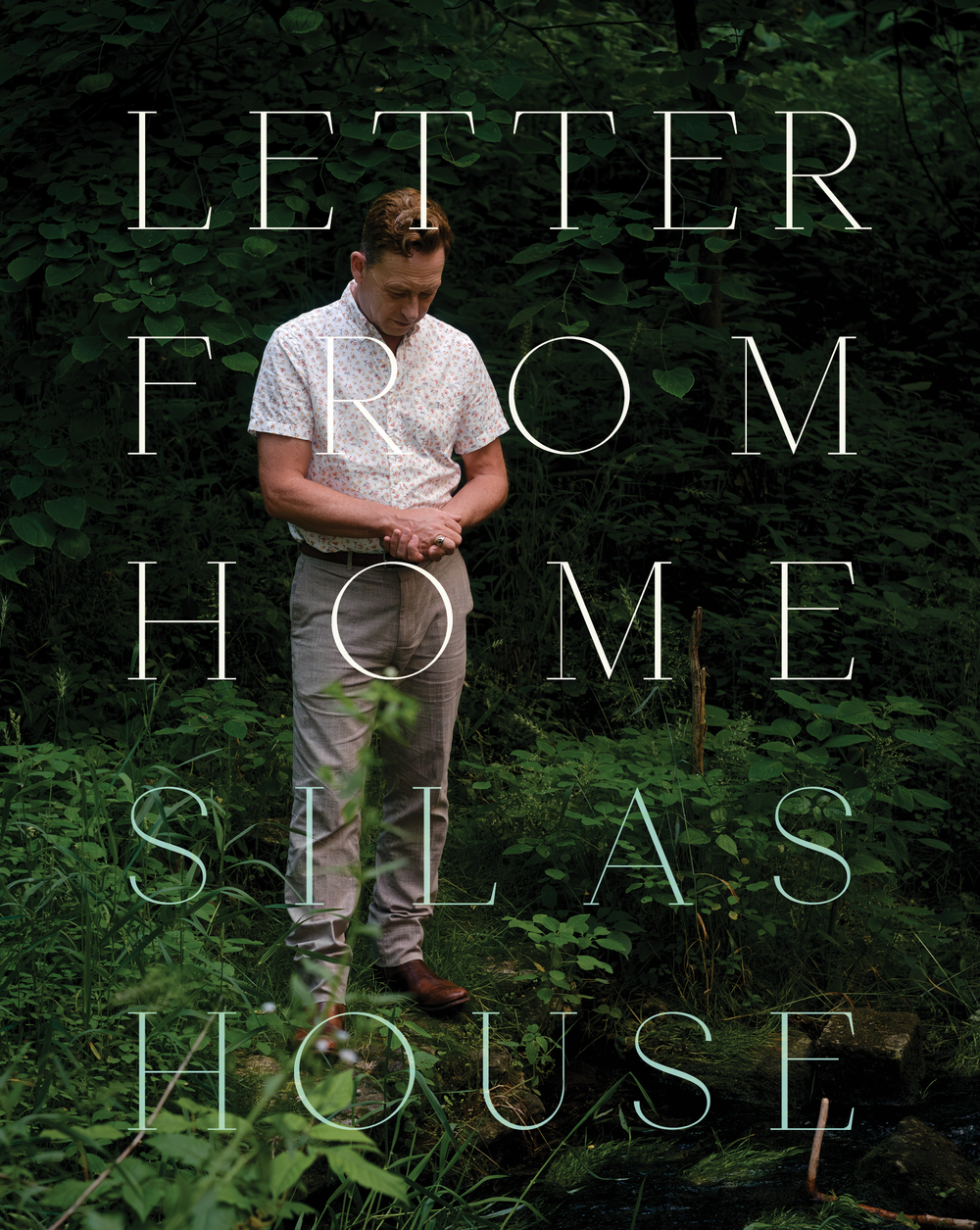

Our mutual love of Rowe’s art was what brought us together initially. When I first spoke to Greg in 2021, I had recently curated “Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe,” the first major exhibition of the artist’s work in several decades, which showcased the High Museum’s vast collection of her art, most of it donated by the legendary Atlanta gallerist Judith Alexander in the early 2000s. As this essay goes to print, “Really Free” is wrapping up itscritically acclaimed national tour, now in Los Angeles at the California African American Museum; and in one of those remarkable twists of fate that is at the heart of this story, a curator there first introduced me to Greg.

Over the course of many emails and phone conversations, Greg’s story unfurled. He has called California home for almost 50 years, but he was born in Madison, Wisconsin, and grew up between Huntsville, Alabama, and Silver Spring, Maryland (the same city where I went to high school). His grandmother, who was an amateur quilter herself, recognized the extraordinary work of a Black seamstress in Cullman, Alabama, and bought a few examples of her work, which helped inspire Greg’s appreciation for the unique aesthetics of Black quilts and other traditional arts. Arriving in 1969 at Georgia State University, he pursued a bachelor’s degree in cultural anthropology, which included a life-changing course with Dr. Mary Arnold Twining. The professor, who would continue her career at Clark Atlanta University, belonged to a generation of scholars associated with Yale University’s Robert Farris Thompson, who pioneered research about African retention in African American art and life.

Greg learned from Twining, for instance, that the sweetgrass baskets made by the Gullah-Geechee communities of the Southern Lowcountry have their roots in centuries-old weaving traditions of peoples once trafficked from the Windward and Rice coasts of West Africa. In 1970, he earned a small research contract from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and, with his soon-to-be wife and fellow anthropology student Kate Young, embedded with the Manigault family, whose matriarch, Mary Jane, was a fourth-generation basketmaker in South Carolina. Their resulting manuscript, which includes Greg’s photographs of the Manigaults at work as well as views of Mount Pleasant churches, juke joints, and landscapes, remains unpublished.

Not long after his communion with the Manigaults, Greg met Nellie Mae Rowe, an artist who had begun decorating her yard in a spectacular way that would cause traffic jams along busy Paces Ferry Road in Vinings, where she had lived since 1939. Rowe only began openly displaying her art in 1968, a pivotal year for Black Americans’ fight for equal rights generally and a turning point for Rowe’s self-liberation in particular, as by then both her second husband and her longtime employers had passed. Refusing to entertain a third marriage and now financially independent, she proclaimed, “Now I got to get back to my childhood, what you call playing in a playhouse.”

In the last decade and a half of her life, Rowe reclaimed her artistic birthright, welcoming visitors to her “Playhouse,” which she decorated with found-object installations, handmade dolls, chewing gum sculptures, and hundreds of drawings. In both her drawing and her environment, Rowe created an alternative space of existence that was far more beautiful, free, and nourishing than the real world, whose many disappointments she lamented in a number of drawings that offered the sentiment “This World is Up Side Down.” In 1973, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution ran a large feature on her that brought an influx of visitors to her door. Then in 1978, Judith Alexander began representing Rowe, who relished the resulting shows in Atlanta, New York, and Washington, that took place before her death in 1982.

Rowe decorated her Vinings, Georgia, home and yard with found object installations, handmade dolls, chewing-gum sculptures, and hundreds of drawings, dubbing it her “Playhouse.” A quilt featuring a red diamond pattern spread across bushes in front of Nellie Mae Rowe’s home in the late 1970s.

Greg met her while working for the South Carolina Arts Commission, which produced one of only two existing films that captured Rowe during her lifetime. The scarcity of high-quality footage helped inspire the New York-based documentary firm Opendox to adopt a hybrid approach to their new documentary about her, This World Is Not My Own, which has been touring the country since its breakout debut at South by Southwest in 2023. (The film will be available for a limited time on PBS platforms.) In order to bring Rowe’s exuberant world to life, Opendox commissioned miniature sets of her Playhouse — made from exactly the kinds of recycled materials that Rowe favored — and recreated scenes from her life through animation and the voice-acting of Uzo Aduba. These playful “reimaginings” were made possible by images from the archives of Atlanta-based collector and photographer Lucinda Bunnen and of Judith Alexander Augustine, a younger cousin of the famed gallerist. Greg’s own photographs were not sources for the filmmakers because they had not yet been discovered. This story marks their first publication.

When Greg sent — early in our correspondence — a document that narrated his encounters with Rowe, which included many of his lovely, color-drenched photographs, he offered me a completely new window into Rowe and her world. All of the images were thrilling, but the ones that showed Rowe standing with her quilts truly made my jaw hit the floor. Rowe was known to be a skilled seamstress. Her mother made beautiful quilts and taught her to sew; and the artist made many of her own clothes, as well as her “children,” the brightly colored and well dressed dolls that she cared for in lieu of the biological children she was never able to have. Many have also pointed to the quilt-like aesthetics of her drawings, which are characterized by bright colors and the rhythmic and fluid piecework that are hallmarks of the improvisational styles most associated with Black quilters. But even Rowe’s descendants — her grandniece Roberta, Roberta’s children, Cheryl and Cathi, and their cousins Ken and Darlene — do not remember much about her making quilts.

Greg’s photographs were the first real evidence of Rowe as a quilter that I had seen. There she was, standing proudly if a bit apprehensively, dressed in a navy polkadotted skirt and a top in her signature color of stoplight green. These were taken during Greg’s second visit, when she mentioned her quilts and he encouraged her to retrieve them — she had eight at that time — from their seasonal storage between her mattress and bed springs. With the help of a friend and neighbor, who also appears in some of Greg’s photographs, she aired them out on her clothesline and fence. In one of my favorite photographs, a stunning quilt composed of diamond-shaped patches of red fabric is spread over several tall bushes, the haint-blue painted siding of her Playhouse rising in the background.

When I first saw these photographs in late 2021, the revelation that Rowe’s artistic practice did indeed include quilting and the possibility that existing examples might join the High’s collection was too thrilling to fully comprehend. Not only would these works complement the High’s existing holdings of Rowe’s art, they could also — along with quilts by other artists in Greg’s collection — contribute to a major initiative I had begun to increase the museum’s representation of Black quilters. Before 2017, the High held only eight quilts made by Black artists, but we will have more than 100 examples before the end of 2025.

Greg and I continued to talk, doing the dance that curators and collectors do, a kind of mutual courtship in which both parties have leverage — one the actual art, the other the institution capable of preserving it for posterity. Sheer geographical distance and various Covid surges made it hard for us to meet in person: At least two trips were canceled at the last minute due to changes in Greg’s health, and the visit that finally brought me to Palm Springs was nearly called off due to a medical crisis in my own family. In the hour between when I walked my daughters to the bus stop that morning and when I boarded MARTA for the airport, I stepped past not one, but two dead birds. “Does one bad omen cancel out another?” I texted my husband.

Nellie Mae Rowe (American 1900-1982); “Untitled (Nellie Riding Chicken),” 1980, crayon and pencil on paper; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Gift of Judith Alexander, 2003.211; © Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/High Museum of Art, Atlanta

After I land in Los Angeles and wait hours for a rental car that never materializes, I arrive at the hotel after the kitchen is closed. I go to bed starving and dejected. The next morning, I re-join the snaking line of undercaffeinated people at Avis car rental — a particular kind of showcase for human exasperation and frailty — and try to keep my cool. My luck begins to change, and I am upgraded to the Mustang convertible of my dreams for my desert journey.

As I drive east with the top down and a Waxahatchee-heavy mix on CarPlay, the good omens begin to flow: I see the giant woolly mammoth sculpture known as “Eddie” on his mountain peak in the Jurupa Valley and a truck hauling not one, but two, trailers of top-loading washing machines, their lids flapping loudly on the open road. The endearing weirdness of people that fills my cup — as my grandmother loved to say, “Normal is overrated” — is on tap, and the feeling that I am exactly where I need to be begins to override my exhaustion and nerves.

By 11 a.m. my red convertible cools in Greg’s driveway, and I swallow my remaining anxiety as he opens the door. He is taller and more tattooed than I expected, but with a gentleness that matches the calming voice I’ve come to know. Reassuringly, he is also not alone, and quickly introduces me to his husband Gordon and friend Glenne, who are there to enjoy a beautiful lunch with us and also help handle the quilts. As I round the corner into the foyer, I nearly trip over the pull-out sofa we will be using as our viewing table. Across its mattress, my hosts have created a textile layer cake of nearly two dozen quilts. On top is a colorful Blocks and Strips number by Alabama quilter Katie Walls, another artist whom Greg photographed and interviewed in the 1970s; then a raucous red, white, and blue Directionals Triangles quilt by the seamstress in Cullman whose name was not recorded by Greg’s grandmother and who first inspired his appreciation for these textiles. Between the quilts are muslin sheets, which help us fold and cover the ones we’ve viewed, moving them into a “seen” pile.

A few more layers, and the first quilt by Nellie Mae Rowe appears: A bold and blocky masterpiece made with predominantly red and white fabrics. Rowe was riffing on two widely used patterns — Courthouse Steps and Log Cabin — but she called this her “Teddy Bear” quilt because in a few of her medallions, she used fuzzy brown fabrics that either came from a disused teddy or maybe just reminded her of one. When I turn over one corner of this quilt and see where Rowe signed her name in red permanent marker, dating it to Fayetteville, Georgia, 1920, I am overcome by the kind of butterflies that I get when I feel the time and space between a long deceased artist and my own life dissolve.

I’ve sensed this kind of cosmic connection with Rowe before. She first started “showing up” for me while I was working intensively on “Really Free” during the depths of the pandemic and the post–George Floyd Black Lives Matter reckoning, which challenged cultural institutions like mine to reckon with how they operate and for whom. My children, then aged about 1 and 5 years old, were at home with my husband and me, while we both tried to work full-time with limited access to caregivers. I kept a video diary about creating “Really Free,” partly designed to engage with our supporters while they couldn’t come to the museum. It is archived on the museum’s LiNK site dedicated to Rowe, and rewatching it now I see signs of the times: tired eyes from endless video calls, the awkward evolution of a bob without access to haircuts, a soft voice meant not to disturb a sleeping baby. But there’s also a perceptible undercurrent of my growing love and admiration for Rowe. As the world turned on its head, her example of fortitude and insistence on life and beauty helped motivate me to keep the exhibition on track for its debut in September of 2021.

Rowe posing with a group of her “children” — dolls which she made from fabric scraps and stockings and accessorized with old wigs and loose jewelry.

One of the big themes of “Really Free” is that what Rowe did by making art and insisting on its visibility — at a time when it was far from safe for a Black woman living alone in Atlanta to do so — was an act of radical feminism. Even if Rowe was not reading the writings of pathbreaking Black feminists like Audre Lorde and Alice Walker, who emerged in the same period, she was certainly aware of Shirley Chisholm’s historic bid for the presidency and probably also of Claudia Jones’ advocacy for Black domestic workers. I recognize the vast gulf between the privileges I’ve enjoyed and the challenges Rowe faced. Still, her radical insistence on breaking free of the gendered roles of caregiving wife and compliant maid to become the artist that only she could become was beyond affirming as I struggled to negotiate the tensions of mothering and careering that brought me and so many other women to our breaking points during the pandemic.

Standing before the Teddy Bear quilt, I am overcome with emotion to know that Rowe made this blanket before she left her parents behind in Fayetteville to move to Vinings with her first husband, bringing it with her and wearing it out with use and washes that left the edges torn and some patches threadbare. To be with a thing that was not only made by her — I’d had that pleasure many times before, after all — but which brought her comfort and warmth throughout a life that knew racism, deprivation, and loneliness. It is the kind of moment that breaks your heart in the best possible way.

There is also a very fleeting quality — an encounter with an object before it reaches the professionalized, preservation-minded pipeline of a museum. In Greg’s possession, these quilts had been in limbo, between their past life of use and before their future of acid-free boxes, white glove handling, and cold storage. The chocolate and auburn strips of teddy bear fabric are just so fuzzy: Reader, I had to rub them, ever so lightly, in a way that few will ever be able to do again, and that privilege was not lost on me, which is why I am sharing it here — so that you too can imagine their plush sweetness under your fingertip.

Greg shows me two other quilts by Rowe, including the red diamond blanket that I had fallen in love with from his photographs. This textile was so well used, it will probably never be able to be hung the way we show most of our quilts, from Velcro “sleeves” that a conservator attaches when they enter the collection. All edges of the red diamond quilt are fraying so badly — speaking to the frequency with which it was pulled up and pushed down as Rowe’s bedcover — that it will need to be more firmly mounted.

The fragility and light sensitivity of cloth is certainly a conservation challenge, but it is one that museum conservators are typically familiar with and have established best practices for. Rowe also worked in materials whose long-term care is far more challenging. Greg has, for instance, about half a dozen Styrofoam trays and plates that Rowe repurposed into canvases, etching her designs so that they have the dimensional depth of a shallow relief. The High already has a number of these, including one that I would consider her Styrofoam masterpiece, a work called “Dear God help Us To Keep Peace.” From a Styrofoam tray once used as packaging for some type of small appliance, Rowe fashioned a blue and bejeweled frame for a hand-colored photograph taken by the aforementioned Lucinda Bunnen. Bunnen had snapped that shot in a hotel room in New York, where she, Rowe, Judith Alexander, and others had traveled in early 1979 for Rowe’s first and only show in the city in her lifetime. Alexander and Rowe are locked in a discussion, not about art (as was once thought) but about what to wear to the opening. The two women did not share the same taste in clothes — Rowe preferred handmade feminine dresses, while Alexander favored shapeless caftans — hence the need to “keep peace” that Rowe calls upon in her title.

Nellie Mae Rowe (American 1900-1982); “Dear God help Us To Keep Peace,” 1977–1979, gelatin silver print, crayon, marker, pen, plastic jewelry, and Styrofoam frame; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Gift of Judith Alexander, 2002.236; © Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/ High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Greg remembers when Nellie took this trip in 1979, because he spoke to her before she left, calling up to see if she would consider selling him any of the remarkable sculptures she made out of chewing gum, and she had promised to “fix up” a few for him. Rowe suffered from migraines and chewed gum to ease the pain. She loved reusing materials, saying, “When other people have something they don’t know what to do with they throw it away. But not me, I’m gonna make something.” One thing she liked about gum, as opposed to the clay that an art student at the University of Georgia once brought her, was that if she wanted to change a sculpture, she could set it in the bright sun until the hardened substance softened. This allowed her to reshape and add accessories to these small human and animal forms — objects like plastic flowers and beads. From the point of view of museum conservation, these additions are actually more problematic than the gum itself. The High is one of only two museums to have an example of her gum sculpture — an adorable mustachioed cat — and while his gum body, now about 50 years old, remains unchanged as far as we can tell, the plastic flower she affixed to his bum is breaking, making it impossible for that piece to travel on the tour of “Really Free,” much to the chagrin of the museums taking that show, who all hoped to include the spectacle of such a peculiar thing.

The same will be true for the extraordinary group of gum sculptures Greg shows me during the second day of my visit. When I return the following morning, the pullout couch has been folded back up, and a large glass coffee table has been restored to its normal position, now bearing seven gum sculptures unlike any I had seen before. Perhaps due to the visceral nature of the material, Rowe’s gum sculptures did not interest many collectors during her lifetime, and few still exist, making Greg’s cache nearly as rare as the quilts. The standout of the group is a head of a woman that Rowe told Greg was inspired by someone she saw in New York. With her formidably stark profile, shiny plastic baubles, and skin painted Pepto-Bismol pink, this is a woman people would have noticed when she walked into a room. A number of Greg’s pieces are distinguished by brightly colored paint — a testament to Rowe’s love of always evolving her artworks and the larger Playhouse installation they were once a part of, as well as her fundamental drive to make things pretty.

For our second lunch together, Greg and Gordon take me to their favorite Mexican restaurant by the Palm Springs airport. When locals take you to a strip mall restaurant, you know it’s going to be good. Over the meals we shared, I learned so much about Greg’s incredible life, which also included time in New York in the second half of the 1970s, where he found community in the post-Stonewall era of gay liberation in Greenwich Village. He became the photographer of genderqueer performance artist Stephen Varble, who created and wore extravagant costumes made — like Rowe’s art — from the discards of modern life. Greg came out, divorced, and as the AIDS crisis intensified, joined the “Rainbow Migration,” moving to the queer mecca of San Francisco. He worked as a photojournalist and quickly became involved in various groups that advocated for LGBTQIA and artists’ rights in the Bay Area and beyond. He later moved to Los Angeles, where he met Gordon, an artist himself, then moved to Palm Springs, where Greg cared for his aging mother and eventually relocated full time to the bungalow that was once hers. Storing his art collection through the increasingly extreme desert climate has been nail-biting at times. The gum sculptures, for instance, were kept in their own minifridge, but with temperatures regularly climbing above 115 degrees in the summer and the instability of our nation’s power grid, this precaution was far from foolproof.

Rowe singing and raising her hands in praise to God, whom she credited with bestowing her artistic gifts.

The very personal connection Greg feels to the artists whose work he collected has made parting with any of their precious objects bittersweet. As the handoff approached, he told me, “I spent just a few afternoons with Nellie, but she has stayed with me for 50 years.”

For me, Greg’s collection became a white whale, and it was stressful to wait until he was ready. But deep down I think he knew that there would be no better place for his rarest of Rowe works than the High, which, in addition to advancing Rowe’s legacy through a traveling exhibition like “Really Free,” has a perpetual display of her work in its permanent collection galleries. Greg also has a soft spot for the High, which was the first museum to exhibit his photographs, in a 1970 group show that was a collaboration with Georgia State.

My visit to Palm Springs helped Greg decide to take the next step. As we ate our lunch specials garnished with sour cream and shredded lettuce, we were all tired.

But we were also full of the warm feeling you get when people turn out to be exactly who you hoped they would be. Someone like Greg, who answered the call to fight the white supremacist, patriarchal, and heteronormative systems that continue to erode this country through a range of actions — from volunteering for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and marching in the Poor People’s Campaign to recognizing and preserving the brilliance of Black women artists who had been ignored for generations — fills me with gratitude and also a sense of purpose. Getting to be a link in the chain of such an artistic legacy is exactly what makes standing next to an open well or knocking on an unmarked warehouse door risks worth taking.

What happened next was the less endorphin-producing bureaucracy of museum work: the negotiation of a contract (some items were gifts, others we purchased); the coordination of shipping (easy for quilts, harder for climate-sensitive gum sculptures); and the formal presentation to the trustees who approve acquisitions. By the end of November 2024, the High had become the proud steward of seven Rowe gum sculptures, her three existing quilts, and 17 other extraordinary quilts made by African American women including Katie Walls, Irene Foreman, Leana Taylor Johnson, and Ethel Cobb. (The baskets, as beautiful and significant as they are, would ultimately not make it into this group, though I hear that another museum with a larger collection of such material is quite keen on them.)

After a period of quarantine and before the committee meeting, we unpack the works in our secure and climate-controlled vault. As I gaze upon the “New York Woman” and “Teddy Bear quilt” — two of the pieces we would showcase at our meeting — they already look different, surrounded by other masterpieces from the High’s collection. They have survived their exodus from and odyssey back to the city of their making — a homecoming that is a reminder of the resilience of people and things, and that somewhat miraculous full circles are possible, even in the most upside down of worlds. ◊

Katherine “Katie” Jentleson is Senior Curator of American Art and Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art, High Museum of Art, Atlanta. She lives in Decatur with her family, where she enjoys gardening and the perpetual calendar of neighborhood festivals across the city. She was born in Northern California and grew up in DC-metro Maryland, but considers herself mostly Southern because of the influence of her mother, who was born in a shotgun house in the Ninth Ward. She earned her PhD from Duke University and is still heartbroken by the loss (on many levels) of Cooper Flagg.