September 3, 2025

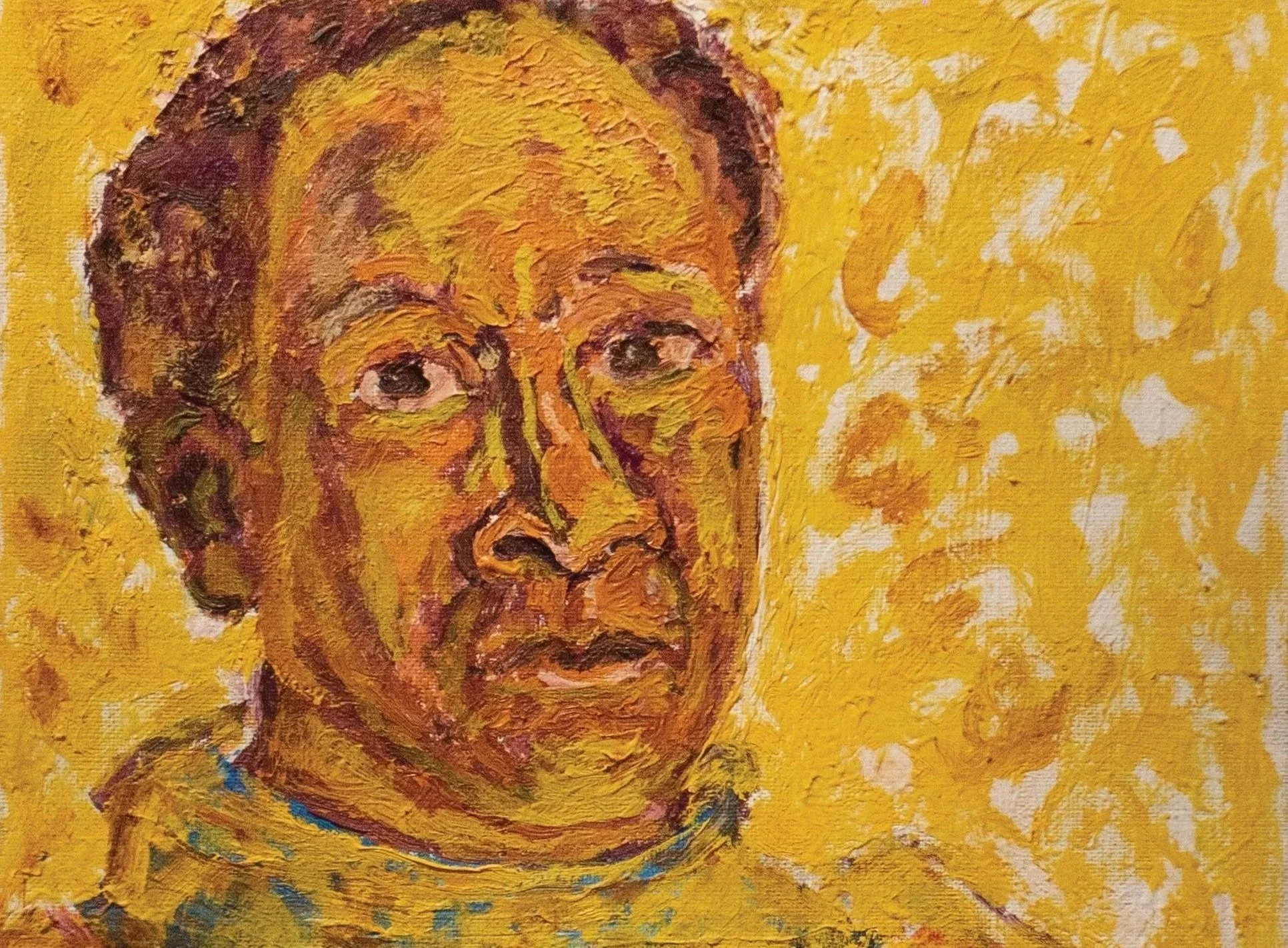

Her coral necklace has slipped inside a fold of her brown linen blouse. Apart from a faint highlight, her dark hair rolled in a loose chignon, almost impossible to distinguish from the stark background. Cheek, flushed with youth. She was already hiding something. The older man next to her, drifting from realism and bathed in a dappled yellow light he thought held sacred power, four years on from attempted suicide. They had so little in common, at first glance anyway, and yet, here they were, one Black, one white, hanging side by side, two artists from Tennessee.

“When I unpacked those two self-portraits, and put them next to each other for the first time ever, I wasn’t quite sure,” said John Daniel Tilford, curator of collections at Oglethorpe University Museum of Art. “And it took me about a day to accept that there was something there between the two of them.

I didn’t see it either. Except that I already sensed a familiar childhood dread creeping back, and sure enough, it would soon get the best of me. (Nights later, I bit my lip hard and woke to blood all over the pillowcase.)

On an early spring afternoon in Atlanta, when yellow pollen dust cast its spell over parked cars and sensitive sinuses, Tilford was walking me through his exhibition titled “Fragile Genius.” Originally from Murfreesboro, Tennessee, he specializes in elevating unsung women artists from the South. “So, I’ve always known about Anna Catherine Wiley’s work,” he said. “Then I happened upon Beauford Delaney’s work and his narrative. And the more I dug, the more parallels I found, and the more I wanted to put them together.” This was the first occasion Wiley and Delaney had appeared in such proximity and, while artistically they seemed an odd couple, their ultimate destinies were too sadly similar. For my part, I needed to stand witness to a curious coupling in the middle of the gallery, where disparate styles converged on a pair of canvases, because that’s ultimately what convinced me these two had the same fire in the mind.

Anna Catherine Wiley, familiarly known as Kate, belonged to a sentimental cadre of American Impressionists whose ranks included Mary Cassatt and Martha Walter. They painted a lot of genteel women clutching parasols or cuddling children. (It’s a recurring art theme that dates to Byzantine-era Madonna and Baby Jesus iconography.) Born into privilege around 1879 — exact dates are uncertain, but she was one of 10 children — Wiley seemed on a path to exceptionality. One of the first female students to enroll at the University of Tennessee, she subsequently left for New York to study at the Art Students League, then won prizes for her soft-focus plein air paintings and exhibited at major institutions. But fairly soon, as her family’s finances eroded, she returned to Knoxville and founded the fine arts program at her alma mater. She also renewed acquaintance with a devilishly handsome older portraitist named Lloyd Branson. No record exists of a romantic relationship. Both never married. But they ran in the same Knoxville art circles, members of the Nicholson Art League and the Appalachian Exposition Association. In 1911, Wiley painted “Green Parasol.” Sunlight filters through the parasol and casts a shadow on a white dress worn by a young woman with windblown hair. Critics drew parallels to earlier works by Claude Monet — same green umbrella, same white gown — although Wiley distinguished the subject by perching her on an Appalachian split rail fence, rooting her in a vernacular specific to the South. At auction in 2024, it attained the highest sale price, $146,400, for any of her work to date.

“It fascinates me because it’s clearly influenced by Monet,” said Tilford, as we paused before the plainly framed painting on loan from the private collection of former Tennessee senator Bill Frist. “And she has an innately striking style. But it’s two to three steps removed, because she got to New York for a few years, but never made it to France. I would consider this one of her great masterpieces.”

Wiley never made it to France, but Beauford Delaney did.

Catherine Wiley, “Self-Portrait,” oil on canvas; Private Collection of Diana Wiley Blackledge

Born in 1901, Delaney grew up in more modest circumstances, the son of a circuit riding Methodist Episcopal preacher and an illiterate housekeeper who would encourage his budding artistic ambitions and inspire an enduring love of spirituals. (His favorite hymn was “Amazing Grace.”) Delaney attended Knoxville Colored High School, and worked odd jobs after classes. Another member of the Nicholson Art League, muralist Hugh Tyler, gave him early drawing lessons. By 1916, Delaney found work as a studio porter, mixing paints and moving canvases in the studio belonging to Lloyd Branson. Accounts vary about how he was introduced there — an imaginative seascape and pastel sketchbooks were possibly involved — but Branson recognized talent in the barrel-chested teenager, and offered formal instruction as part of payment for his employment. He stayed for six years.

No one can say for sure, but I like to imagine Catherine Wiley, wearing her coral necklace, crossing his path then, even if only while he stoked the coal stove and ran errands for Branson.

With encouragement from his mentor, Delaney eventually departed for Boston to continue his studies, and by 1929, made it to New York, right as the Harlem Renaissance peaked and the Great Depression turned the world blue. His first real breakthrough came shortly after, when he was chosen to participate in a group show at the Whitney Studio Galleries (later renamed the Whitney Museum). Delaney found community in avant-garde circles, both uptown in Harlem, but also in Greenwich Village, becoming friends with Henry Miller, Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keefe, W.C. Handy, and Carl Van Vechten. And one afternoon in 1940, while he lived at 181 Greene Street, there was a knock on his studio door as Delaney was listening to Bessie Smith on his Victrola. When he opened it, young James Baldwin was standing outside. (A mutual friend had sent him.) In search of creative guidance, the teenager from Harlem would first become his protégé, then lifelong friend, and ultimately, a guardian when Delaney could no longer silence the voices in his head.

Catherine Wiley, “Green Parasol,” 1911, oil on canvas, 33 ⅝ inches by 25 ⅝ inches; Collection of Senator and Mrs. Bill Frist

“So this is ‘Greene Street’?” I asked, facing a boldly modernist streetscape that signaled Delaney’s shift toward abstraction. Henry Miller described it as “mad with color.”

“It really shows the sophistication of Beauford Delaney, even as early as the ’40s,” said Tilford.

The figure of a Black man appears to be working on a pushcart, or maybe a car, but it’s hard to tell what’s really going on, and a red line running through the middle of the canvas fractures the scene.

“It’s weird,” I said. “Almost like two different dimensions.”

“Exactly,” said Tilford. “And he really did live in his own world. It was a fascinating world, but it was different. He left this remarkable body of work behind but I think he paid a great price for his creativity.”

Let’s get to that in a bit. Briefly, in 1953, at the urging of Baldwin, Delaney left to join his friend in Paris, a city where racial and sexual differences were far more tolerated.

We stepped in front of two blue abstracts, also intentionally side by side. The ones I had come to see. They are extraordinary departures from earlier work for both Wiley and Delaney, and speak to their precarious states of mind, not because they project distress but rather the indigo mood of each is reflective of a paradigm. And trust me, I know something about blue paintings. It was the predominant color in my father’s art.

Delaney had a head start. Given the time and place, he was more likely destined to wind up in the realm of abstract expressionism. This untitled watercolor emerged during his residence in Clamart, a quiet suburb of Paris. Struggling with chronic depression and loneliness, and drinking far too much to tamp down disordered thinking, he needed a break from his hectic social life on the Left Bank. The piece is awash, a purely emotional precursor to the more complex oils that would come later, and I loved the reckless splashing of concentrated, luminous color.

Beauford Delaney, “Greene Street,” 1946, oil on canvas, 16 inches by 20 inches; J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Arts, Virginia Museum of Fine Art © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

For “Study in Deep Blue,” completed sometime before 1927, Wiley abandoned her pretty maternal scenes, shifting to a darker palette entirely for a nocturnal seascape, real or imagined. We leaned closer, examining her tempestuous brushstrokes.

“This is unlike anything I’ve ever seen by Catherine,” said Tilford. “It was in her family’s possession at the time of her death.”

The background appears to be a shoreline in deep shadow, with tiny yellow lights twinkling, and a winding stream of white that expands as it approaches the foreground. It reminded me of Sachuest Bay — Wiley had painted one summer in Newport, Rhode Island — along a beach where I used to swim. An indistinct shape, possibly a woman in a billowing dress, clings to a rail in the lower left corner.

“You know that could be the stern of a boat,” I said, squinting at the midnight blue. “And that white paint is the wake. That could be the wake from the boat. Someone’s on the stern, and the boat is going away from shore.”

I recognized that paint.

Beauford Delaney, “Untitled (Clamart),” 1959, watercolor on paper, 23 inches by 18 ⅛ inches; Estate of Beauford Delaney Collection of Sasha and Charlie Sealy © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

My college offered a famously comprehensive art history class that was a snare for students who thought it would be an easy pass to spend an hour once a week looking at slide shows of Renaissance masters in a darkened auditorium. No thank you. I knew better. My parents had insisted on hauling their children along to gallery openings and museum exhibitions, hellbent on an excruciating program of cultural enrichment. Besides, I had firsthand knowledge of the tumultuous lives of artists — especially the ones who struggled to pay the bills, let alone cling to their sanity. On the upside, we were always welcome to play with the art supplies in my father’s studio, learning to express ourselves among his canvases of ocean swells and crashing waves. A Remington manual and paper for me; crayons, pencils, brushes, paints for the others. Although I learned the hard way how much Titanium white cost after throwing a tube at my sister Kaki’s head in a hissy fit. Got a spanking, had to clean up the splatter, and lost my allowance for a year.

“I’m convinced that if Wiley had not been institutionalized, her style would’ve evolved further,” said Tilford.

By 1929, Catherine Wiley was herself drifting out to sea, unanchored and storm tossed, after too many creative disappointments and deaths in the family. Her friend, Lloyd Branson, gone as well. She ended life committed to the State Lunatic Hospital at Norristown, a psychiatric asylum in Pennsylvania, remaining there for almost 31 years. While her family sent her gifts of basic art supplies, and she composed illustrated cards (Norristown was one of the first hospitals to provide arts-and-crafts programs to its patients), Wiley never painted professionally again. Accounts differ, but medical records indicate she died due to sepsis from a gangrenous foot wound.

Catherine Wiley, “Study in deep blue,” oil on canvas; McClung Historical Collection

My mother, also known as Kate, was briefly committed in 1963. Shortly after discovering she was pregnant again, and I’m only guessing as the medical records no longer exist, this may have triggered her nervous breakdown. (That’s what they called being overwhelmed by a depressive disorder crisis back then.) Money worries, unquestionably another factor. My father sent her away with the assistance of the family doctor and a friend of the family who was a shrink with a fancy practice in Manhattan. Weeks before, John F. Kennedy had been assassinated, which would become a bizarre footnote during her care at a psychiatric hospital close to our home in Putnam County, New York.

They put her on Thorazine.

I was so little at the time, and only vaguely recall a single visit, when Dad was finally allowed to bring me. She was sitting in a public area with other patients, all in bathrobes, playing bridge, like it was some damned country club. Mom seemed detached, uninterested in us. We didn’t stay long. She also missed Christmas that year, and I can’t help but think back on subsequent nightmarish holidays, now aware of this context.

Cured? Hell no. Coping mechanism? The worst. After her release, one of her doctors advised my mother, when she felt a little stressed, or a little anxious, to have a little drink. Remember, this was the Swinging Sixties. He also showed up at my parents’ fabulously artsy parties, in a clear violation of practice described as a “dual relationship” by the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. And he bought art from Dad — or maybe those paintings were bartered, because that happened regularly when my parents were strapped for cash. On top of that, I recently discovered he was hired as an expert witness by the legal team defending Jack Ruby, who shot Lee Harvey Oswald, and the declassified FBI file released under the Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act included uncorroborated, derogatory, salacious details of this doctor’s sexual history — “in the event the Bureau desires to instruct the special agent in charge … to convey this information to the prosecuting attorney in Dallas County.”

Is it irrational to be freaked out by this?

Mom became a binge drinker, and only after she was gone did I even begin to call her an alcoholic, let alone admit the wounds attendant on her mental instability.

Many of these details were missing until I rifled through the letters my father wrote as Mom recuperated. Pleading, professing love, promises to make more money. Hopes for recovery. Allusions to her fearful and confused state. Dad never threw out correspondence, no matter how intimate or awful, but at some point shoved these in a manila envelope addressed to me. I doubt he intended for me to share his words with strangers. Mom’s condition was a closely guarded secret.

An excerpt from Friday, December 20, 1963, three days after she was hospitalized:

We all miss our wonderful, loving Muv [his nickname for her] so awfully much, but we feel so relieved knowing you are being cared for by the right people. I realize how difficult this all is for you and how you must miss the children, but the sooner you do get well, the sooner they can have you with them again. We have three unusually understanding children and they are all so concerned for you. Each night as we say our prayers together, there is an especial “God bless Mommie and help her get well” and this is fervently felt by all of us. I suppose you’ll never be too happy about me and some of the decisions I was reluctantly forced to make during these weeks past. Perhaps our very lives and relationship has been permanently altered by all this. I have been warned to expect it — but that is of no importance to me now. I still love you dearly — even more than ever before — and I will do anything in my power to get you well. I would do this even if it meant losing you, your love, and the children. That my darling is how much you mean to me. We have lived through so many bad times together — more than our share. I am working hard to make a far better future for us — and that we shall have at any cost. Just take care of yourself and let me do the rest — for I want to get you home with us all at the earliest possible date. And we pray for the time to pass quickly for you and for us.

With much much love from your own

Jim

P.S. I am getting a fresh girdle down to you.

This bit about the girdle wrecked me.

When you have parents who are wildly talented, and also wildly flawed, it’s crucial to remember the good days, not only the nightmares. Mom gave great hugs and incredibly thoughtful gifts. Dad made us hand-drawn birthday cards and wrote impassioned letters. He taught me cribbage and a love of the blues. She walked in the post office lobby on the day I pulled the freeride letter to Vassar out of the mailbox, and together we jumped up and down, shrieking like little girls. On my sleepless nights — what the French call la nuit blanche — this is the joyful memory that soothes me most.

My parents eventually found more happiness, more stability, although they never kicked the addiction and left behind a trail of bills. After Mom died, my father descended into paralyzing grief for a time, what I called his purple haze period, and his paintings became terrible, frightening. Dad was emotionally shuttered, but feelings have a way of materializing on canvas — his oceans overwhelmed by streaks of purple ugly as a bruise.

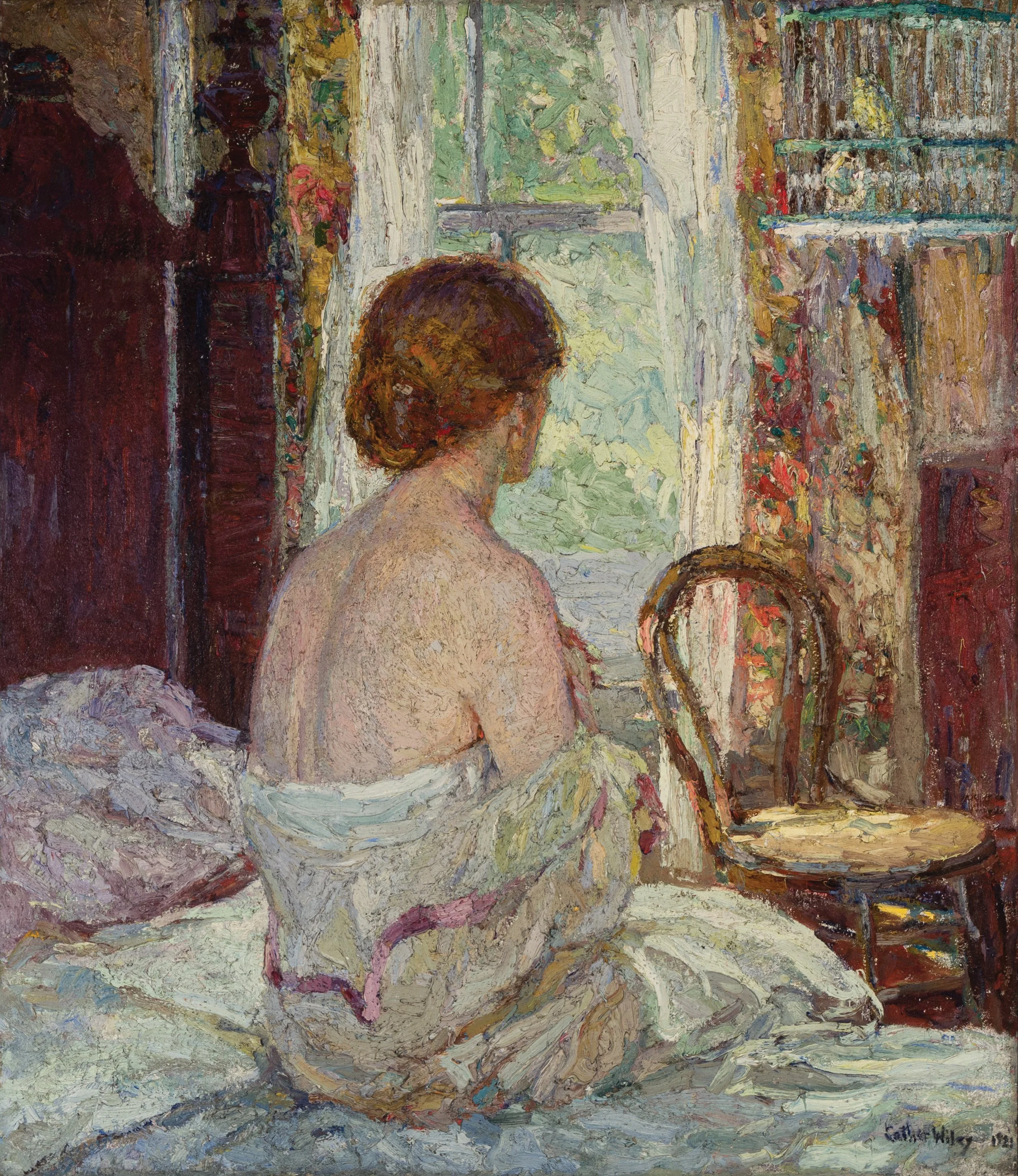

Catherine Wiley, “Morning,” 1921, oil on canvas, 47 inches by 41 inches, Knoxville Museum of Art; 1972 gift of the Women’s Committee of the Dulin Gallery

Mental health used to be one of those top-tier conversation killers, sometimes it still is. Children were taught not to talk about troublesome issues in polite company, particularly, but not exclusively, related to loved ones who might be neurodiverse, chronically depressed, hearing voices, or suffering delusions. Both my parents grew up embedded in that cultural norm, when these challenges were deemed so shameful, so deeply stigmatic, you were more worried about what other people thought, and less about how you should feel. It’s why some of my younger siblings only heard about this confinement secondhand, and why we still, to this day, tend to hold secrets from each other. Some truths are unbearable, even at a remove, and compassion fatigue is real.

Mom had an antique coral necklace like the one worn by Catherine Wiley. My sister Melissa chose it in a round robin when we divided up her jewelry. She sent it to me a few years later, stuffed inside a plastic bag, the peachy orange remains of marine invertebrates coming loose from the stringing, along with a note, and I’m paraphrasing, but it essentially read: “Broken. You fix it.”

Tilford guided me to the final Wiley painting in his exhibition. An autobiographical portrait of a woman seated on the edge of a rumpled bed, her face hidden, back exposed, as a nightdress slipped off her shoulders.

“Was she put away because she was inconvenient or was she put away because she just was not able to cope anymore?” I asked.

He paused to consider.

“She was probably put away because she was inconvenient. It’s a combination of withdrawal and violence. She will seclude herself in her room for days, if not weeks at a time, and really neglect her personal wellbeing in every sense of the word. And then when she does emerge, there are episodes of her shredding her brother John’s clothing. She had this veneer of gentility and politeness that was masking the underlying problems with her health. And then that veneer begins to crack and wear away. I think the family tried to hide it behind closed doors.”

Tilford told me the coral necklace remains with Wiley descendants, as does a painting they have titled “The Demon.” As it is so out of character for her legacy, he didn’t think it belonged in the exhibition, but shared it with me later. The portrait shows a grinning man with a goatee and enormous ears, wearing a red painter’s smock and holding a paint palette. It bears an uncanny resemblance to an early photograph of Lloyd Branson. Really disturbing, raising more questions than we have answers for, since details of her life remain sketchy, especially after she was confined to Norristown. Her family was given the chance to take Wiley back into their custody; despite her expressed desire to go home to Knoxville, they declined.

The two of us also looked at a final Delaney painting simply titled “Abstract No. 9.” A frantic swirl of yellow that requires contemplation to reveal subtle layers of color, like iridescent bubbles in a tide pool of melted butter. Tilford considered it a jewel of the exhibition.

“He often painted with yellow as a form of self-medication to lift up his spirits,” he said.

“So this is his happy color?” I asked.

“It was very much his happy color. Although this, there’s so much more than just yellow, but the yellow was taking center stage.”

Beauford Delaney, “Abstract no. 9,” ca. 1963, oil on canvas, 51 ¼ inches by 38 ⅛ inches; Estate of Beauford Delaney, The Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

In 1961, while traveling to Greece, Beauford Delaney tried to kill himself, and on his return to Paris was diagnosed with acute paranoid delusions aggravated by alcohol. He had a few more good years, mounting solo exhibitions, setting up his easel and painting sunny garden scenes while visiting James Baldwin at his home in Saint-Paul de Vence. Slowly, however, his demons caught up with him. Collector and friend Solange du Closel had enrolled Delaney in a health care program for artists, and his last few years were spent at the Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne, an asylum dating back to 1651, in Paris’ 14th arrondissement. The walled campus has courtyards, sculpture gardens, and internal allées named for creative thinkers, some troubled themselves, like Camille Claudel, Charles Baudelaire, and Gérard de Nerval. (Coincidentally, this is where Thorazine was first tested on male mental ward patients in the 1950s.) Delaney was assigned to a shared room in the southeast corner of the property, with unrestricted access to the gardens. A poignant photograph by Max Petrus, taken during a visit there in 1976, shows Delaney and Baldwin together outside in the sunshine. One disheveled, wearing a white bathrobe with the hospital insignia, his face drawn, hair and beard shaggy; the other dressed in a groovy dashiki and bellbottoms, at the height of his fame. They are holding hands, standing naturally close, as intimates do.

Delaney spent the last year of his life slipping into dementia.

So much has been written about the intersection of creativity and madness. Scientists, philosophers, poets, trick cyclists — some suggest that artists are highly susceptible to mental disorders while others romanticize their fates. I think this is succumbing to causality: we notice their differences because they’re exceptional. Yet, knowing their lived experiences and complicated histories certainly helps frame where their art is at. (Don’t care what anyone says. Still glad I skipped Art History 105.) Of all that’s been said regarding the fragility of artists, I love best what James Baldwin shared about his dear friend’s otherworldly spirit. In the introduction to his collection of essays, The Price of the Ticket, Baldwin wrote: “Lord, I was to hear Beauford sing, later, and for many years, open the unusual door.”

Before leaving Oglethorpe, I turned back to the two blue paintings. Gave me half a mind to pull my father’s purple haze out of the closet and finally hang it.

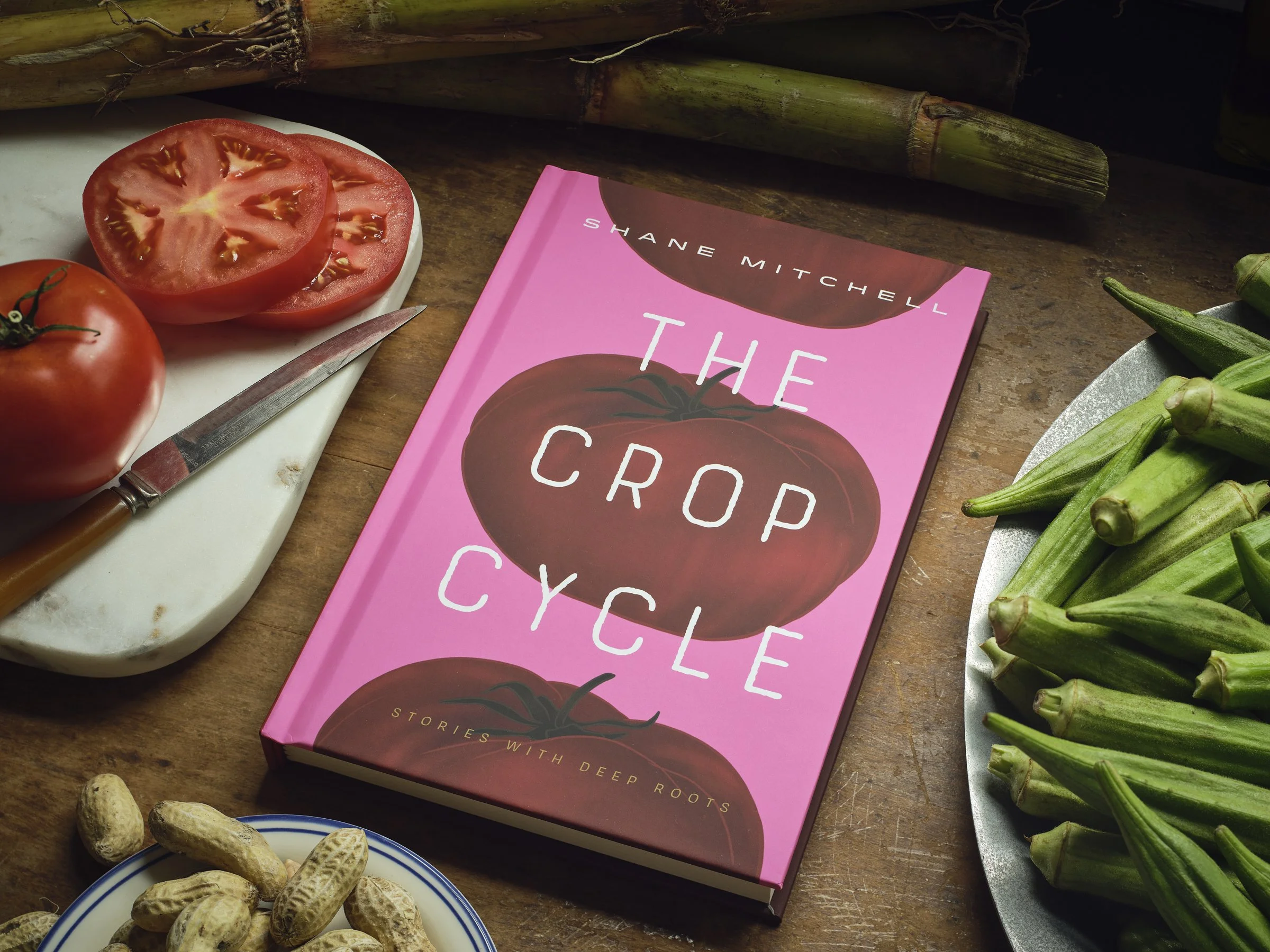

Shane Mitchell writes narrative nonfiction and cultural criticism. She is the recipient of five James Beard Foundation awards, including two M.F.K. Fisher Distinguished Writing prizes, for her stories on consequential crops and problematic food histories. Earlier this year, her collection of essays, The Crop Cycle (Bitter Southerner Publishing), was longlisted for the Pen America Art of the Essay prize.

—

Opening painting: Beauford Delaney “Self-Portrait,” 1964, oil on canvas, 16 ⅛ inches by 13 inches; Tennessee State Museum, Nashville; Tennessee Historical Society Collection (2001.46) © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York