Words by Mike Kane | Photos by Teague Kennedy & Mike Kane

Guy Bradley gave his life to save South Florida’s tropical birds, becoming one of the environmental movement’s first martyrs

January 14, 2026

July 8, 1905. A blood-soaked, small wooden skiff bobbed in the waves, adrift off the eastern short of Cape Sable in Florida Bay. Inside, a man lay dead from a single gunshot wound, a revolver by his side.

There are a million ways to die here in the waters surrounding the Everglades and the Ten Thousand Islands. These include: venomous snakes, alligators, crocodiles, sharks, swarms of mosquitoes, punishing heat, and the near constant threat of tropical storms and hurricanes. The man had understood that, here, nature gives no quarter.

He also knew that this vast and wild frontier provided cover to murderous outlaws, poachers, bootleggers, fugitives, and a Seminole tribe fighting against their forced removal by the United States government.

He was keenly aware that certain men wanted him dead, simply because his job was protecting local birds whose plumage had become more valuable than gold in the Gilded Age lust for exotic millinery. Still, he persisted, paddling and slogging across vast distances in an audacious bid to defend the defenseless, and knowing it would likely cost him his life.

His name was Guy Bradley, and we are chasing his ghost.

It’s 8 a.m. at the marina in Flamingo, Florida, and we look like two deranged beekeepers, our bodies fully covered in mosquito netting, having just been pursued across the parking lot by a thick swarm of bloodsucking savages. Yes, the mosquitoes are that bad here in July. Google it. Our kayaking trip has been moved up by four hours due to the expected 115 degree heat index. It becomes suddenly, and painfully, clear why we are the only two people here today, more sadists than tourists. Summer is the low season in this town at the southern tip of the Everglades. Very low. But coming here in July deepens our appreciation for the harsh life settlers faced on our nation’s tropical frontier, and we have a story to tell.

As we push our kayaks into the water, we are greeted by a crocodile named “Half Jaw” who warily escorts us to the Florida Bay. “He’s cool,” we’re told, “but gets cranky if you get too close.” I plunge my paddle deep in the water to steer clear of this beast. (I read later that he almost killed a guy who flipped his sailboat in the marina.) Naturally, Teague, ever the intrepid photographer, wants to get close enough for a dental inspection. This is my first time in Flamingo, but it’s old hat for him. He has been obsessed with Bradley, and the mystique of this place, for decades. His award-winning screenplay, Plume, is based on Bradley’s life and the eccentric characters of the Florida frontier. We’ve teamed up to pursue film, podcast, and other adaptations. Think of this story as a preview.

As we paddle into the open Florida Bay, the tide pushes us to an area called “Snake Bight,” just east of where Guy Bradley was shot. It is teeming with life.

Author Mike Kane “wet walks” through a cloud of ravenous mosquitoes.

Lemon and bull sharks glide past, one whipping beneath the bow with a foamy splash. A stingray lurks just beneath the surface as another crocodile slips past giving us the side-eye. The tide is receding, exposing a muddy lunch buffet that offers up small fish, insects, and crustaceans for a flock of roseate spoonbills, a beautiful pink wading bird with an aptly named beak. A spindly-legged red heron does a frenetic feeding dance, white ibises and great egrets stand at attention just beyond our kayak’s reach, seeming to know that we come in peace.

More than 350 bird species have been spotted in the Florida Everglades in recent years, and the list keeps growing. Hundreds of thousands of wading birds return here every winter, according to avian ecologist and photographer, Mark Cook, who is writing a book about the return of the American flamingo to this area. This is a birder’s paradise.

Our guide is Garl Harrold, a local legend who seems to be on a first name basis with every creature in the area. As we gawk at the birds, Garl smirks, “this is nothing, come back in April.” Most of the wading birds leave here in the summer for shallower water, but they will return in stunning numbers to nest in the myriad keys and rookeries of Florida Bay. The wondrous sight of so many gorgeous birds in one place should not be taken for granted. Audubon estimates that there were once more than one million wading birds in the Everglades.

Early pioneers in Flamingo, at the southernmost tip of Florida, suggested naming their new town “End of the World, Florida.” In 1893, it was accessible only by boat, and hemmed in by a vast wilderness unfit for most humans. Frontier life here was less about “settling” than it was surviving. In his book, Death in the Everglades, Stuart McIver writes that Flamingo “was about as far away from civilization as any American can run. . . . It was a place where few questions were asked. Or answered.”

The lawless landscape provided cover for fugitives like the notorious, alleged mass murderer Edgar Watson. Legend has it that he shot and killed the outlaw Belle Starr in Oklahoma before fleeing to Florida. Years later, after a reign of terror among the Ten Thousand Islands, he was shot dead by an angry mob and buried in a shallow grave. Peter Matthiessen’s acclaimed novel, Shadow County, was inspired by Watson and other wild characters of the Florida frontier.

As we duck our kayak into a shady cluster of tangled mangroves, instantly we are enveloped in a cloud of angry mosquitoes. We frantically struggle to find our head nets. Their shrill, piercing buzz is so loud it seems the swarm is inside our brains. Suddenly, sharks seem far less scary.

Settlers here would spend stifling summers covered in body netting, armed with palm branch swatters and smudgepots — small chambers of burning charcoal belching thick smoke to scare off the “skeets.” They fished and hunted to make ends meet, and nature provided for them in abundance. Some would guide wealthy adventure seekers down the river sloughs shooting at alligators and snakes just for laughs. Birds were blasted from trees for target practice. Wading birds like flamingoes were hunted for meat as well as their exotic plumage.

A roseate spoonbill takes flight.

Guy Bradley and his brother Louis grew up hunting throughout the wilds of South Florida. Guy was a skilled marksman and enjoyed the spoils of hunting. He found ample opportunity, though his family had moved here in 1898 to chase another dream for striking it rich. Industrialist Henry Flagler, who founded Standard Oil, was planning to extend his railroad from Miami to Key West. Guy’s father, Edwin, was convinced that the rail would run through Flamingo, at the time a scrappy little hamlet of rickety shacks on stilts. Edwin purchased some cheap land with visions of hotels, beaches, and tourists sipping fruity drinks, but that dream would turn to dust when Flagler decided to build down the Atlantic coast through Key Largo instead — bypassing Flamingo entirely. The Bradleys and a few other local families would have to find another way to survive. So Guy and Louis spent endless days wading through the swamps with Walter Smith, an ornery Confederate veteran sharpshooter who relied on the Bradley brothers’ expertise and cunning in the wilderness.

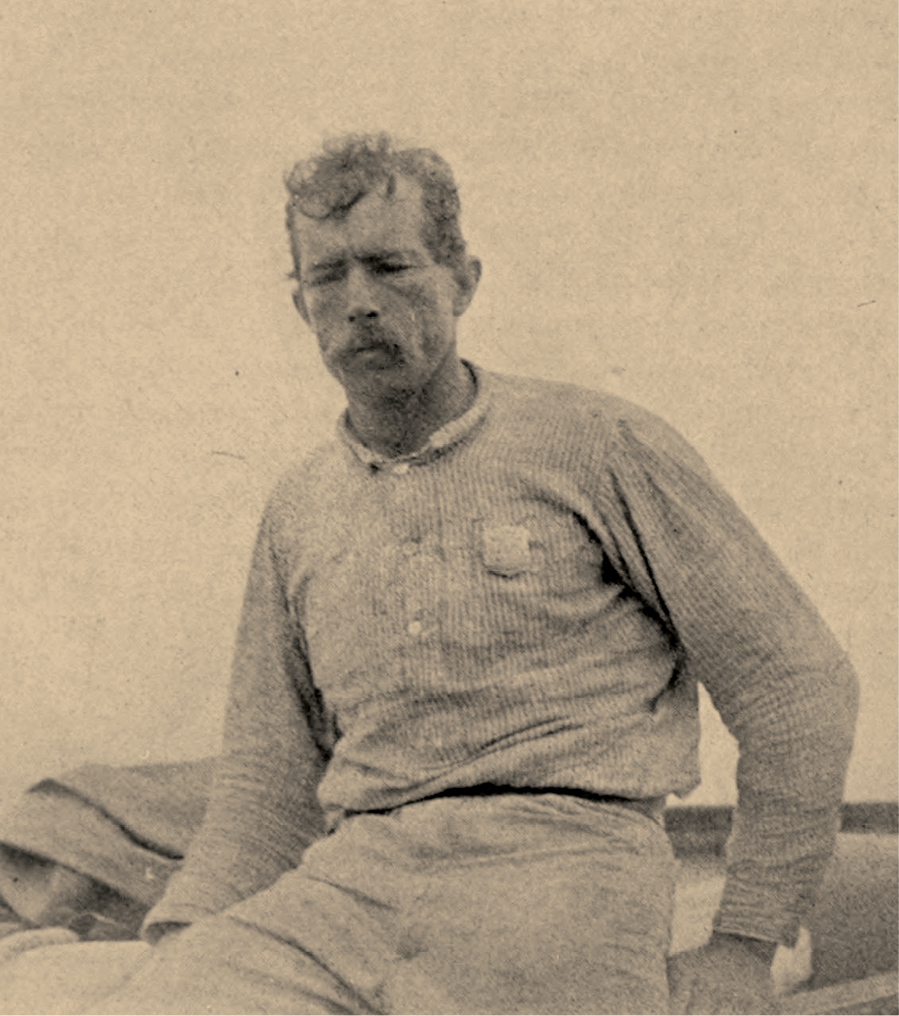

Above: Bradley became America’s first game warden in 1902, hired to protect native birds from south of Naples to Key West.

Expertise is something we could really use right now as we are slogging, aka “wet walking,” through a cypress dome — this time without Garl, our human safety net, who wasn’t available, which was very unfortunate for us. Cypress domes look like tree islands carved by a slow moving river of grass. But they are actually freshwater swamps with large bald cypress trees in the center, surrounded by smaller trees that give them a dome-like appearance. The water is impossibly still and gets deeper and murkier around the massive tree trunks in pockets known ominously as “alligator holes.” We are intruders entering a hidden realm, walking slowly, quietly. The dense canopy above blots out the sun, casting a soft, ethereal glow that feels mystical.

We zigzag our way through the swamp, eyes peeled for cottonmouth water moccasins. These wetlands also teem with crocodiles, panthers, bears, and — more recently — the highly invasive Burmese python. “Bring Polarized glasses so you don’t step on a gator,” Garl had warned us earlier. Strike one. My vision is further obscured by the thick mosquito netting draped over my face, the sweat dripping into my eyes, and bright green plants growing on the water’s surface. I am blind-slogging through a prehistoric slurry of god knows what, while the hum of swarming insects grows ever louder. This feels like strike two. Our walking sticks plunge 2 feet or deeper into the muck. “Don’t step there, or there … or there,” says Teague. “Also, don’t touch that tree! I think it’s poisonous.” God, I wish Garl were here.

(A note of caution, dear reader: We recommend in the strongest terms that you use an experienced guide if you go on one of these treks in the summer.)

Frozen in place, and sort of losing it, I snap back, How about I hang your lens bag on this tree of death and I get the fuck out of here? The “skeets” are now covering my hands. “Good luck, suckers!” I taunt them, fully confident in my gloves’ protection. A minute later, blood is seeping through the fabric. Strike three. I’m out. Teague soldiers on snapping photos of wild orchids, bromeliads (a cousin of the pineapple), and unnervingly large insects, including a lubber grasshopper the color of a traffic cone.

When we finally return to the safety of our car, a billion mosquitoes follow us inside. I spend the next 10 minutes speeding up and down the road with all the windows down, shit-talking them as the breeze sucks them out of the vehicle.

These swamps were also crawling with renegades 125 years ago, poachers seeking their treasure at “Cuthbert Rookery,” an isolated, secret spot that was bejeweled with countless egrets, ibises, herons, wood storks, roseate spoonbills, and other wading birds. The breeding grounds were named after George Cuthbert, a ship captain who traveled some 80 treacherous miles into the swamps in search of the fabled roost. His discovery netted such a haul of plumage that he was able to purchase half of Marco Island with the proceeds. Cuthbert famously refused to divulge the hidden location and fled the area fearing retribution. His hunting partner was soon murdered in the small fishing outpost of Chokoloskee, presumably by someone seeking his secrets. Rumors spread quickly, and poachers from all over the country came in droves to grab the Everglades’ seemingly endless supply of feathers and hides.

A snowy egret stands sentinel high above the shoreline of Florida Bay.

A world away from Flamingo, the Gilded Age was in full swing. Wealthy industrialists celebrated their sudden and immense wealth by acquiring land and grand buildings. Their wives flaunted their social status by wearing dead birds on their heads. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, millineries in New York cranked out ornate hats festooned with the plumage, and in some cases the stuffed carcasses, of exotic birds as fast as poachers could kill them, turning the pristine wilderness of Monroe County, Florida, into a place of boundless treasure. At the height of the Plume Boom, an estimated 5 million snowy egrets, herons, and other wading birds were being slaughtered each year, pushing some species near to extinction.

In 1886, ornithologist Frank Chapman took a famous walk through Manhattan counting birds, 40 species to be exact, affixed often in grotesque ways atop women’s hats. His article in Forest and Stream magazine ignited outrage among conservation and bird enthusiasts. A group of Bostonian women led by Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall organized a plume boycott and founded North America’s first Audubon Society. The Massachusetts organization played a crucial role in the passage of the Lacey Act of 1900, which banned the interstate transport of birds killed illegally. But that ordinance only turbocharged the black market. By 1903, snowy egret plumes were worth twice as much as gold per pound. Poachers blasted defenseless wading birds in sickening numbers, primarily during mating season when they displayed nuptial feathers — elegant plumage grown to attract mates. The birds were easy prey because, even under a hail of gunfire, they refused to leave their chicks. The hunters would cut a trail of carnage through rookeries, ripping off the birds’ feathers, known as aigrettes, leaving carcasses and unhatched eggs to rot in the sun. Baby chicks were left to die, crying in their nests.

During the Gilded Age, the fashion industry had an insatiable appetitie for exotic plumage. (Library of Congress)

By 1902, the birds and the activists trying to protect them were losing the battle in Florida. State authorities and the Audubon Society decided they needed a full-time enforcer, someone with deep and intimate knowledge of this territory, a local who knew the players in this dangerous and cruel game. No one was more qualified than Guy Bradley, and noted conservationist Kirk Munroe recommended him for the post, describing the 32-year-old as “clean-cut, reliable, courageous.” In his job application, Bradley wrote, “Since the Game laws were passed I have not killed a plume bird for it is a cruel and hard calling notwithstanding being unlawful.”

Although Bradley had hunted plumes for years, the waning bird populations had begun to weigh on him, and he accepted the job, becoming America’s first game warden and the deputy sheriff of Monroe County. His jurisdiction stretched from south of Naples all the way to Key West, about 100 miles by boat. His mission was clear: Stop the poachers, or die trying. He was paid $35 a month, hardly a windfall considering he had a wife, Fronie, and two young sons to support.

As game warden, Bradley saw entire rookeries being eviscerated, and it shook him deeply. Keys where he once had seen birds by the thousands, were suddenly devoid of life. For the next three years he chased poachers relentlessly, at all hours, into some very remote and dangerous places. His days often ended in a primitive tent on a damp patch of dirt, far from civilization, with unseen dangers lurking under the pitch darkness of night. Those dangers included the poachers themselves. As he had acknowledged to his potential bosses, “It would be necessary for a warden to hunt these people and hunt carefully for he must see them first, for his own sake.”

Bradley’s dedication wasn’t always appreciated in the previously un-policed wilds of Monroe County. Still, he pressed on. He tried to educate locals, communicated directly with poachers, but was mostly offered a deaf ear. He posted warning signs. He deputized his brother Louis and enlisted trusted locals to be lookouts in the hard-to-reach backwaters and marshes.

Although he had been a friend of the family for years, Walter Smith turned quickly against Guy and Louis when they began enforcing the Audubon Model Law. Smith rejected Bradley’s authority and taunted him mercilessly, brazenly shooting birds within his earshot. He likely saw Bradley as a traitor, turning against local traditions. Undaunted, Bradley arrested Smith once, and his oldest son twice — prompting Smith to threaten to kill him if he arrested either of his sons again.

Roseate spoonbills perched above the mangroves. Rising sea levels have forced them to nest farther inland in recent years.

On July 8, 1905, Bradley heard the unmistakable sound of gunshots piercing the still morning air around Oyster Keys, located 2 miles offshore from Flamingo. He knew very well that there was a colony of cormorants there, and he recognized the schooner anchored just offshore. It belonged to Walter Smith. Bradley calmly said goodbye to his wife and set out alone in his small rowboat with his .32 caliber revolver, knowing full well he might not make it back.

Friends found his skiff the next day roughly 10 miles to the west. Bradley lay alone in the boat, dead from a single gunshot wound. Smith turned himself in to authorities in Key West claiming he shot Bradley in self-defense. He claimed it was Bradley who fired first. Despite the fact that Bradley’s weapon was found with the chamber full, Smith was eventually freed due to lack of evidence.

Justice was often a hopeless objective here in the wilderness, and Bradley might never have expected it anyway. His obituary was published in Bird-Lore magazine:

A home broken up, children left fatherless, a woman widowed and sorrowing, a faithful and devoted warden, who was a young and sturdy man, cut off in a moment, for what? That a few more plume birds might be secured to adorn heartless women’s bonnets. Heretofore the price has been the life of the birds, now is added human blood. Every great movement must have its martyrs, and Guy M. Bradley is the first martyr in the cause of bird protection.

— William Dutcher

Dusk at Flamingo’s Guy Bradley Trail, as the setting sun paints the horizon.

The miracle of the light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slow-moving below, the grass and water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades of Florida. It is a river of grass.”

— Marjory Stoneman Douglas,

The Everglades: River of Grass, 1947

Guy Bradley’s violent death became national news, reported in the New York Times, The New York Herald, and Forest and Stream, among other publications. The articles sent a jolt through a fashion industry that was still rewarding poachers for their prizes. Consumers all over the country who had been unaware of the real cost of their plumes were appalled by the murder, and plumage quickly fell out of favor. The prices of feathers dropped accordingly, and the illegal killing of wading birds became far less lucrative. Public sentiment was turning and the government took notice. All migratory birds were placed under federal protection in 1918 under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Within just a few years, the Everglades’ shallow waters were again reflecting the graceful dance of the red heron and the pink glow of the roseate spoonbill. And by the 1940s, “there were roughly a half million wading birds” in the Everglades, according to Dr. Paul Gray, science coordinator at Audubon Everglades.

The few remaining human residents of Flamingo were forced out not long after the Everglades National Park was established in 1947. Their cluster of battered stilt cabins has since eroded into the sands of time, replaced by a quiet campground, a small lodge, and housing for park rangers and staff.

Today, Everglades National Park stretches across more than 1.5 million acres of cypress swamps, impenetrable mangrove forests, river sloughs, and sawgrass marshes that spill into the estuaries of Florida Bay. The ferocity and fragility of nature create a delicate balance of life in this dynamic biosphere, the only tropical environment in the contiguous United States, though it is still recovering from decades of ecological abuse. As Florida boomed in the 20th century, many considered the Everglades to be a worthless swamp. Large portions were drained to create fertile farmland, its freshwater redirected to fuel rapid real estate development. An ecosystem that took 5,000 years to form was nearly decimated in just a few years. Wading bird populations dropped, once again, due in large part to destructive water management programs.

Agriculture, urban development, and the effects of climate change — including rising sea levels — continue to be mortal threats to the Everglades, which is now roughly half of its original size. Fortunately, a massive preservation plan is well underway. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) was approved by Congress 25 years ago, with a goal of keeping clean freshwater flowing down to the bay. It’s the largest hydrologic restoration project in U.S. history, according to the National Park Service, and is essential to all life in South Florida. Freshwater from the glades fills the Biscayne aquifer, which provides South Florida with its drinking water. “What’s good for the birds, is good for the humans,” says Gray.

The restoration has been, for the most part, a bipartisan effort, though some advocates are concerned that the state might wrest too much control away from the Army Corps of Engineers and push back against federal environmental regulations. It also remains to be seen how staffing cuts at the EPA and the National Park Service could impact the Everglades. Nevertheless, overall, the restoration appears to be working.

The revered American flamingo, which was essentially wiped out by plume hunters, has returned to the area. It’s believed that some of these flamingoes were swept up by 2023’s Hurricane Idalia and blown north, likely from Cuba and Mexico. Time will tell if the current ecosystem will provide for them, but ecologists, like Mark Cook, are hopeful. “If we get it right, these birds will come back,” he says. Populations of wood storks, herons, and roseate spoonbills are also trending in the right direction. “Seeing an abundance of a common species, performing their natural functions in the environment, means things are working again. It touches your heart,” Cook says.

“When I see those beautiful pink birds against the azure blue of Florida bay, it seems like the bay is complete.”

— Avian Ecologist Mark Cook

A torrential summer downpour soaks the “River of Grass.”

Teague takes a bite of his Cuban sandwich. He seems very pleased. Just an hour ago we were aimlessly trudging through muck in a feeble attempt to understand what life was like for early pioneers trying to survive in the Everglades. We have a KIA sedan with AC and GPS. They had a canoe and the scorching sun to guide them. We’re covered in mosquito nets and DEET. They carried burning pots of smoke. We have Dasani water iced in a cooler. They often had to collect rainwater to drink. We’re worried whether Flamingo’s only restaurant will be open for dinner. They worried about being dinner.

As we sip Coronas and luxuriate in the restaurant’s cool interior, watching the setting sun brush the stormy clouds with a peach and yellow glow, we are reminded that Bradley never got to experience this kind of comfort. Certainly he could have lived an easier life in Miami or Key West, but he strikes us as the type of intrepid, old soul who is hard to find in an age when success is often measured in “clicks” and “likes.” We leave Flamingo with a deeper and more profound appreciation for the scope and significance of his work protecting birds, the grace and beauty of his charges, and the courage it must have taken to do a job that was more likely to result in death than in a promotion.

Back at the marina we see signs for the Guy Bradley Visitor Center. Although his memory might not be preserved in many history books, here, near the site of his former homestead, Bradley’s life and sacrifice have not been forgotten. Bradley reminds us that one person’s actions can be a catalyst for change. He never set out to be a “martyr,” but over three short years, his work yielded real results in Monroe County. And his death helped propel a national movement that brought some majestic birds back from the brink of extinction.

Bradley’s body was laid to rest in a coffin made of cypress boards on a shell ridge on Cape Sable. A hurricane later washed his grave out into the waters that are sparkling just outside our lodge window.

On our first night here, I had noticed a set of complimentary ear plugs and a noise machine on the bedside table. “The walls must be thin,” I thought to myself. The next morning, I was jolted awake by a series of loud squawks and a handsome bird chilling on my balcony railing, backlit by the sun, rising over Bradley Key, a new dawn breaking at “the end of the world.” ◊

Mike Kane is an Atlanta-based writer, director and the founder of Rock Canyon Creative, a collective focused on multiplatform nonfiction and brand-focused storytelling. Prior to that, he worked at CNN for over 20 years. Mike is also a private chef and loves a good yard project.

Follow him @mikekanecooks or online @ mikekanecreative.comTeague Kennedy is an independent media producer. He holds a BA in Film from the University of Central Florida and an MFA in Film from the University of Miami. He has produced multiple documentaries and TV specials for CNN, HLN, BBC America, Travel Channel, Weather Channel, and others. He is currently working on a film adaptation of the Guy Bradley story. Portions of his screenplay, “Plume,” have been excerpted for this article.

Epilogue Image: “Voyaging in the Everglades.” Photo by Brown Brothere

Top: Roseate Spoonbill Illustration by John James Audubon - 1836