ART by PATRICK MARTINEZ

Our Kyle Tibbs Jones sits down with Issue No. 12 cover artist, Patrick Martinez

November 19, 2025

Patrick Martinez, thank you so much for talking with us. In January of this year, I was at the Whitney in New York City walking through a group exhibit themed around immigration. I loved your piece so much I took multiple photos. I was blown away by how they hung it up high like an exit sign. Just so beautifully executed in all the ways. A few months later, we were talking about our fall cover. Dave Whitling, our creative director, said, “I have an artist to show you.” I said, “Dave, I’ve been meaning to show you this piece from the Whitney.” It was your work, Patrick. We were both showing each other your work. It was kismet. We said in unison, “Let’s put Patrick on our cover.” So, thank you, thank you for being here.

TBS: Our magazine focuses on culture, art, literature, music, food, and the environment. The storytelling layer that runs across all of our work is steeped in social justice and making the world better. How did you find yourself making these neon pieces that point us to a better world?

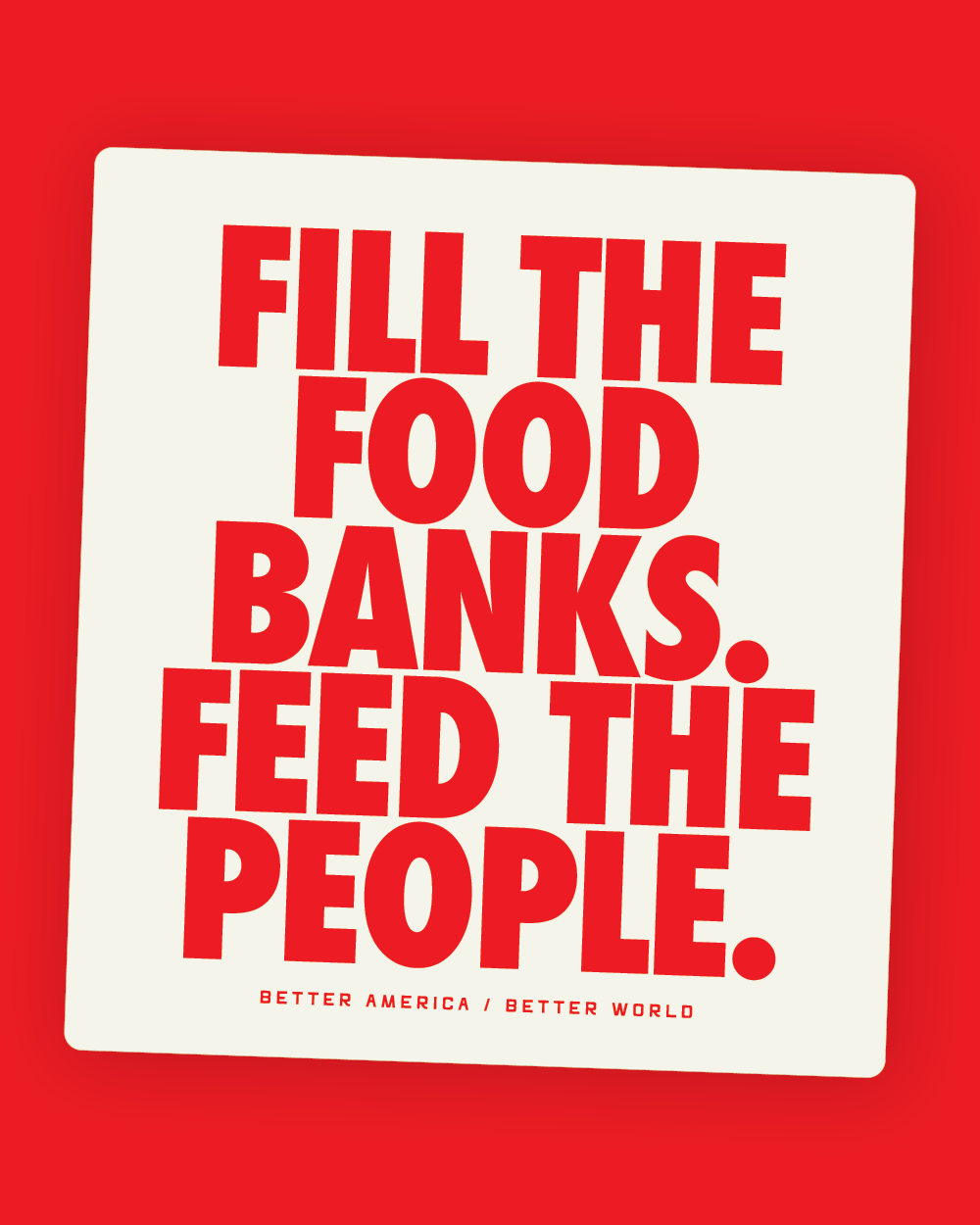

PM: With the first iteration of Trump’s presidency, I was thinking, I am being persecuted and people are being scapegoated and blamed. And I knew that was going to happen this time. Years before that, I was thinking about storefront signage in Los Angeles, specifically, community-based stores, services like laundry, notary public, or check cashing. I know that people in different parts of America can identify with those things. But for me, it was about taking that format and speaking to the passerby, to change the signage, to speak to something that was coming. By the second or third neon that I made, the work felt like a warning sign. A lot of them come from protest language. Whether I’m thinking about Frederick Douglass or James Baldwin, there are things that need to be said, again, right? Refreshed in the context of contemporary art but in storefronts. That’s my subversion. That was my idea to subvert commerce or like, you know, your business-as-usual kind of day.

“Migration Is Natural,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 25.75 inches by 36 inches by 4.375 inches, 2019.

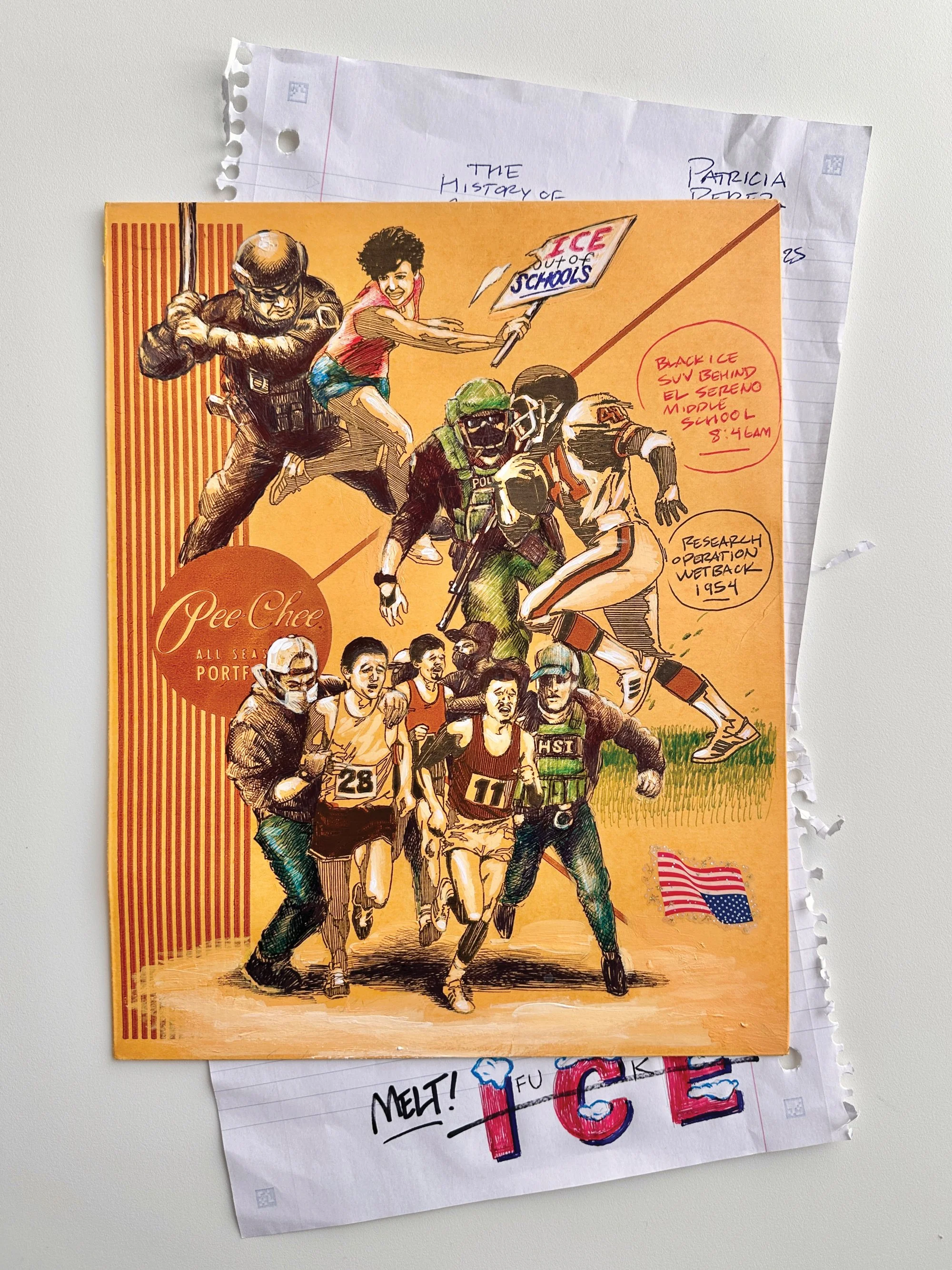

“Ice Kidnappings Pee-Chee 1,” by Patrick Martinez. Bic pen, stickers, notebook paper, acrylic on found Pee-Chee folder, approximately 10.75 inches by 16.75 inches, 2025.

TBS: Is that where you hung them originally? In actual storefronts?

PM: Yeah, like advertising. I started making them, probably in 2008, and wanted to quickly hang them back in the places that they were inspired by. The people I’m talking to are, you know, working people, people that are just trying to get by, my cousin, my uncle, my niece, my nephew … Because they were already coming from protest language and warning signs, and things like that, actual physical signs. So I [created] online signs and people started taking them to protests, and then I started making them available at protests.

TBS: So, you’ve done these signs in neon and cardboard?

PM: Yeah, because it’s something you can take with you.

TBS: Patrick, in restaurants, shopping malls, zoos, museums, there are signs, symbols that help people find their way. It’s actually called wayfinding. I feel like your work is helping us find our way.

PM: Oh, wow. Thank you. That’s strong. In the context of contemporary art, neon is a very, kind of, seductive medium. My goal was to make it urgent, bold, and legible. The light contaminates the whole area. It contaminates and brightens it up, right? So, in these dark times, people feel that kind of urgency, the stress of, you know, the administration kind of coming down on them. Also, economic violence, things like that, these things I wanted to populate the storefront, but also to light the way. They’re not gonna save the world, but I imagine dark streets with these things being on.

TBS: How many of these neon pieces have you made?

PM: I have not even counted them, but there’s many. I started off slow. God, then it was like 2016, ’17? I just haven’t stopped since. Maybe 30 a year? So many, you have to count!

“Dena,” by Patrick Martinez. Stucco, acrylic paint, spray paint, tile adhesive, and latex house paint on scorched panel. Two 4 foot by 4 foot panels; approximately 4 feet by 8.5 feet installed, 2025.

TBS: Patrick, we’ve looked at a lot of your work across the Internet. You do so many different things. Which art form takes up most of your time? Or do you hop around from medium to medium?

PM: Well, I’m lucky enough to be able to bounce around. Like, right now, I’m working in Pee-Chee folders. After I finish this kind of giant painting for a triennial show that is gonna happen in L.A. in October that we’re gonna install next month.

TBS: You’re painting on what kind of folders?

PM: Sorry, I’m drawing on Pee-Chee folders. They’re scholastic folders that kids used to have in middle school and high school. I kind of hijacked them because they were illustrated [with themes like] agricultural farm scenes or a pilot with a plane. So my thing is to update them. I remember at a very young age, there were police officers and that kind of energy in our high schools. I never understood why they were in our high schools. I wanted to kind of subvert these folders, updated from the 1950s, and read those scenes, connecting youth and authority issues. So, I was drawing these portraits in pen, like you would when you were in high school, middle school, drawing on your Pee-Chee folder. Like you would draw the band that you were into or write notes on it, whatever. It was a very inexpensive folder, but it was connected to America, in my mind. [I was] always kind of highlighting authority figures, figures brutalizing Americans, you know?

“Hold the Ice,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass,

36 inches by 22 inches, 2020.

“BIPOC,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 9 inches by 24 inches by 5 inches each, 2023.

TBS: Yes. Did you grow up in Los Angeles? What was your life like?

PM: I grew up in Pasadena, and then I was in East L.A. I’ve always been here, and the city informs the work I make. I was always making art. And when I was a teenager, I picked up graffiti. It was the early ’90s, so the uprising was happening as I was doing graffiti … you could see smoke coming from a liquor store while you’re thinking, Oh, we’re gonna go to the graffiti yard tomorrow.

TBS: Rodney King?

PM: Yeah, Rodney King. The ’92 Uprising. All those things are kind of, like, in the DNA of what informs the work; and not because I was meaning to do it, it was just one of those things that you can’t ignore. It’s even more apparent today.

TBS: Patrick, in today’s environment, it takes real courage to make this art. Where does that come from?

PM: It’s strange because I think about it now, and I go, why would I continue to do something? I’m a very logical person. I’m very analytical. But I’ve always felt like it was an autotelic thing. Like, it needs to happen. And at any cost. It sounds dramatic, but I need to carve out time to make this. I always thought, even in my undergrad at the ArtCenter, the work that I was making then is really the same work that I’m making now. That was in 2002, 2003, 4, 5. And, you know, the professors didn’t understand it. They didn’t know how to critique it. But I knew that I wanted this stuff to exist. I didn’t think: I want to show them in a gallery; I want it to be in a museum. I wasn’t even thinking like that, to be honest. You just want it to exist. Yeah, ’cause it’s magic to make art.

TBS: Patrick, we feel like that about the work we do at this magazine. When I was 12 years old, my mom would say, “You carry the weight of the world on your shoulders.” And I’d be like, Well, I don’t know how else to be. I have to do something. And it just sort of carried through my life. I’m a lot older than you, but it never leaves, it’s always there. Maybe it’s just part of who we are.

PM: It is, and I don’t know how to explain that. And then people say, “Oh, you’re an activist.” I’m like, I observe things, and I observe things that are disgusting and deplorable, and I have to say something about them, right? It’s like … I’m a human being, and I care. How could I not? Right?

“Fleeting Bougainvillea Landscape,” by Patrick Martinez. Stucco, neon, acrylic paint, spray paint, tarp, and latex house paint on panel, 7 feet by 8 feet by 5 inches, 2023.

TBS: Right. How are the people in your life doing? What is happening there now? How close is it to you? We’re not in L.A. obviously, but here in Georgia our governor has also agreed to call up the National Guard. So distressing.

PM: It’s very close and it’s disrupting. Like your nervous system is shot, because of what’s already happening, like the genocide, Ukraine, all of the stuff that’s happening on the interior of America or with the current administration, and then L.A. with the fires in January, and the kidnappings happening months later. It’s too much. And, we have cameras and stuff at my studio and then at my home. And that’s on top of what we’re already downloading from social media. And then you see people patrolling your streets, and you know people that are fighting for their lives. You know artist friends that are fighting for their green cards. And they can’t work, they can’t get their license. Because their green card is expired and they can’t get it renewed. And people are on the edge, because they know that they can be snatched up. And it’s all profiling because they’re snatching up citizens too, right?

There’s a restaurant across the street from the studio here. It’s a Mexican restaurant, and because of ICE they lock their doors during the time that they’re open. They don’t want anyone dangerous coming in. If they see them, they won’t open the door. So, to eat there, it’s almost become a speakeasy. Like, you have to knock and be admitted, and they have to know that you’re a good person.

People are not gathering as much, you know, because they’re thinking about that kind of brutality happening to them. It’s terrifying. The administration knows what they are doing, because it’s showing the brutalization of people to show that he’s making progress or cleaning the streets up. But people are being brutalized. LAPD coming down on protesters that were unarmed and just peacefully protesting. The news, legacy media was saying that there were riots. It was just people trying to protest because they are not down with seeing their communities being ripped apart and people being stripped from the places where they’ve built a life. They’re trying to rip them apart from that, and send them to who knows where.

“Same Boat (Martin Luther King, Jr),” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 30 inches by 36 inches, 2017. “Let’s Get Free,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 20.5 inches by 26 inches, 2017. “America is for Dreamers 3,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 31 inches by 50 inches by 3 inches, 2017. “Brown Owned,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 20.5 inches by 26 inches, 2017. “America is for Dreamers 2 (Los Dreamers),” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 25 inches by 36 inches by 3 inches, 2017. “America is for Dreamers,” by Patrick Martinez, edition of three. Neon on plexiglass, 20.5 inches by 26 inches, 2017.

TBS: Where do we find hope? Is it in the actual act of pushing back?

PM: For me, it’s like screaming. Art is screaming out into the void, right? It’s like the receipt of me being alive, and these are the things that I have to say. Like, I want people to know that I was pushing back in some way. And it’s not just because I want to be some type of successful artist or anything like that. I’ve always wanted to push back and I’ve never wanted to decorate rich people’s homes. I mean, there’s no shame to that because I love beauty and all. But my thing was to create to be helpful, in a way. And I think that creating things that speak to the time that you’re living in is important and urgent, and that’s where my making comes from. I’m responding to things in real time, and for me, it’s gonna create a document, especially when people are trying to erase histories, burn books. Trump or the administration is talking about editing shows at the Smithsonian, right? And fucking with the art … I’m in some of those collections, you know? But at the end of the day, I want to make the work he will try to burn.

TBS: You want it to be the truth.

PM: Yeah. Because he’s trying to edit, you know. Politicians are letting this shit happen, where it’s like, rewrite history, right? And in my paintings and other work I’m embedding history into it, cementing histories in it, and hopefully they cannot erase those. But that’s what I’m doing. My approach is to include a lot of these quotes and these portraits and these happenings inside the work that I make and try to get them into people’s collections or museum collections. I feel like it’s a responsibility to do that, to make work that pushes back on everyone that is down with what’s happening right now, Democrats and Republicans that are, you know, letting things happen, the people that are, you know, OK with how things are right now. I’m not. And that’s the work that I’m making.

“LA Tile and Stone,” by Patrick Martinez. Stucco, neon, acrylic paint, spray paint, latex house paint, tile adhesive, and ceramic tile on panel, 84 inches by 84 inches by 4 inches, 2022.

“Ghost Land,” by Patrick Martinez. Stucco, ceramic tile, neon, cinder block, acrylic paint, mean streak, bougainvillea plant, spray paint, and latex house paint on panel, 18.5 feet by 6 feet by 10.5 feet, 2023.

TBS: Right. We’re so thankful you’re making it. You know, we’ve talked about the neon, and you’ve talked about the folders, the urgency, the signs and the quotes and the important bits of history and making this record. Has your current work diverted you from other art you might be making, or is there art you’re putting on the back burner?

PM: I’ll say this, you know, at some point, I would like to, like a lot of people, have a dignified and peaceful life, where I can choose to paint, like, I don’t know, a bed of flowers. You know what I mean? Not that I’m tired of responding, but I don’t wish to have to, just like everybody, have this conflict. The situation that we’re all living in is exhausting.

TBS: It is exhausting. So many people need and deserve a softer life, but that feels impossible while this is happening.

PM: I actually enjoy making the work that I make, and I get lost in the process of it. The receipts are always great. But I do want to spend time with my family. I do want to carve out time and be responsible in that way, because I know that’s, in a way, part of pushing back and having a healthy family. Joy is resistance, they say. Joy sustains the activism, too, right?

TBS: 100 percent. Joy and love will sustain us.

PM: We have a 4-year-old daughter. My wife and I live right here above East L.A. My family is my refuge, and they support me. I want to live a life that’s like, not just about responding 24/7, and being the person to lean on. I do know that that’s important right now. I want to be useful in these times, but that’s not everything. At the end of my life, I want to be a moral person, die a moral man, but I also want peace. I want to know what it is like to go hiking and go places with my family and not think about these things.

“Then They Came for Me,” by Patrick Martinez. Neon on plexiglass, 30 inches by 26 inches, 2016.

TBS: Patrick, we so want that for you. We also want to amplify your message. Is there one of your pieces you’d like to see everywhere?

PM: I do like “And then they came for me.” Neon, because right now, I think it resonates with a lot of people and how they feel. They’re nervous, because the current administration is derailing a lot of people’s commerce here in America, right? Their livelihoods. So, after they’re done with that, who are they gonna come for? Who’s next?

TBS: That’s right. I think people need to understand that. That’s why we chose your art for the cover. Fascism doesn’t stop. It will not stop. Patrick, we never thought we’d see this. Two years ago, when they rolled back Roe v. Wade it seemed like dark foreshadowing, but I don’t think any of us could have predicted how bad things would get for so many. We took our eye off the ball. We didn’t know how hard we had to fight for democracy.

PM: It’s true. Eye off the ball for sure.

TBS: Patrick, we always ask this as our last question, how can we help you?

PM: Hmmm, please pay attention. Also, feel free to use my work as a starting point to say something. Whether you’re an artist or someone that’s wanting to go out in protest or say something on their front lawn, or, I don’t know … just use the work how you see fit. That’s the point, that’s what it’s for, especially the neon work. Share it, do what you want with it. It is there to amplify what you’re thinking, or as a starting point, so you can push back in some way. It’s rooted in history, most of it, and those are deep roots. Those are rich roots. You can stand firm on that. ◊

Patrick Martinez (b. 1980, Pasadena, California) earned his BFA with honors from ArtCenter College of Design in 2005. Patrick's work has been shown domestically and internationally and resides in the permanent collections of The Broad, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA), Buffalo AKG Art Museum, the Rubell Museum, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, the California African American Museum, the Autry Museum of the American West, the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Tucson Museum of Art, the Pizzuti Collection of the Columbus Museum of Art, the University of North Dakota Permanent Collection, the JPMorgan Chase Art Collection, the Crocker Art Museum, the Escalette Permanent Collection of Art at Chapman University, the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at UC Davis, the Rollins Museum of Art, and the Museum of Latin American Art, among others. Patrick lives and works in Los Angeles, California, and is represented by Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles.

—

Top Photo by Johanna Brinckman