In the South of 90 years ago, young African Americans started dancing the Lindy Hop. It was an act of resistance, an assertion of freedom against the discrimination and violence of Jim Crow. Today, swing dancers across the South — black and white together — pay proper tribute to that legacy.

In Atlanta’s historic Vine City neighborhood, hidden among the trees overgrowing the lot at the corner of Sunset and Magnolia, is a barren concrete slab. On this spot, in the heart of an early-1930s African American community, Atlanta was first introduced to what would become “America’s National Dance”: the Lindy Hop.

Teenagers from all over the Westside would flock to the Sunset Casino and Amusement Park. The cavernous pavilion, which had been converted to a dance hall, featured a rotating cast of local talent along with the best swing bands in the world — Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald. The Sunset also held Saturday afternoon dances and weekly Jitterbug contests. At the Sunset, for just 25 cents, the city’s black youth could briefly escape the ravages of the Depression and Jim Crow and dance their cares away.

I had hesitated to visit the site where the Sunset Casino once stood. I had learned about the Sunset from books. I had dug up, in the archives of the Atlanta Daily World, colorful descriptions of the dances there. I had found old advertisements for performances featuring long-dead artists I have come to love.

But I don’t have any kind of connection to the people in these stories — or really to this place at all. I’m a recent transplant to Atlanta and to the South. I am white. My entry point was through the dance itself, an art form that I, like many others, had come to love — but only later sought to understand.

As I stood there, I tried to picture the old streetcar stop, where trolleys full of students would step off and line up at the entrance to the dance hall. I imagined the sound of boys playing basketball, the smell of popcorn in the air, and the delighted laughter of children riding a carousel. I tried to conjure the feeling of a crisp fall night in 1937, carnival lights twinkling all around, walking into the Sunset. I imagined that moment when the scorching sounds of a blaring trumpet filled the packed dance hall, when the drummer broke loose in a percussive flurry, and when the Duke himself started pounding the ivories.

The crowd must have gone wild.

And I imagined the Lindy Hoppers. I saw them in my mind, showing off the acrobatic moves they had been practicing on the street or to records in their living room. I imagined them complaining about the heat inside the hall, using handkerchiefs to wipe away sweat. I imagined them swinging out hard, experiencing the same exhilarating feeling of pure joy and connection that I feel on the dance floor today. And I pictured the smiles on their faces, every one of them black.

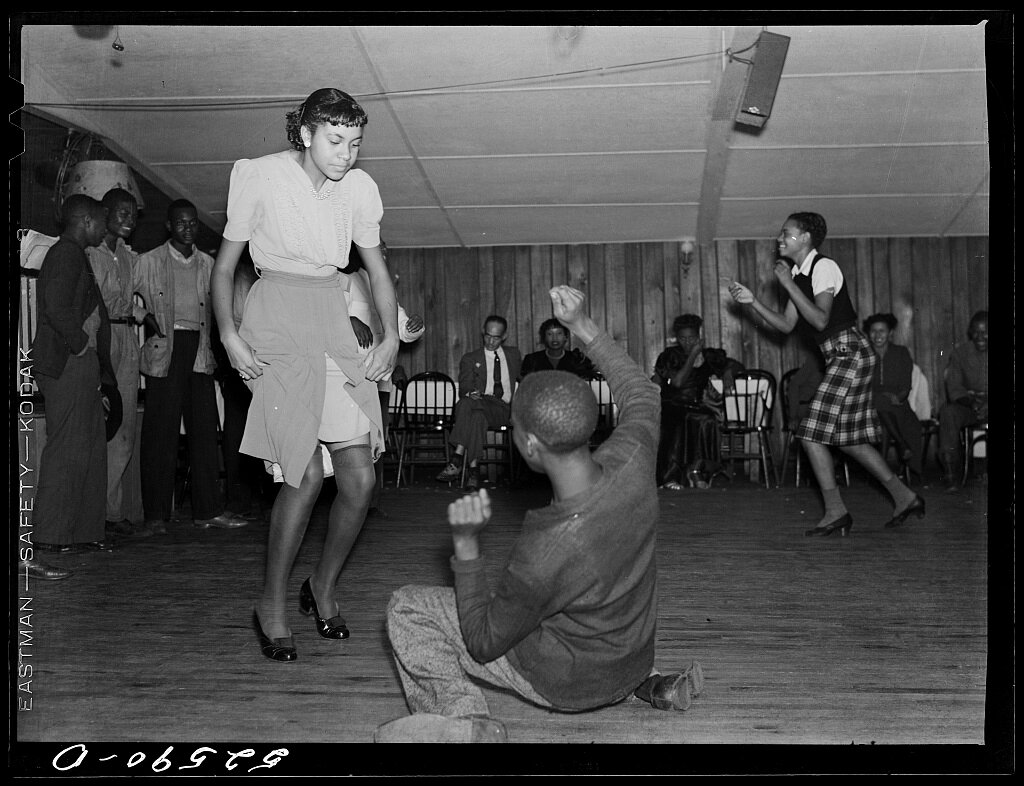

Juke joint jitterbugging in Memphis, Tennessee

Swing Dance is a modern umbrella term that describes a range of partner dances associated with swing music. But the realest swing dance is the Lindy Hop. The Lindy Hop was an art form invented by black dancers at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem during the late 1920s, and almost the entire history of African American dance was its source material. The dance is based on a core move called the "swing out," in which two partners engage in a reciprocally counterbalanced swinging movement around each other. The dancers then layer on infinite embellishment and elaboration, including the acrobatic “air steps” for which the dance is known. Lindy hoppers may use rehearsed choreography when competing or performing. When dancing socially — as we normally do — Lindy Hoppers, like jazz musicians, improvise all their movements in real time, creating a wholly new dance at each moment on the floor.

The Lindy Hop evolved through the growing popularity of big bands in the mid-1930s, especially as dance troupes began touring and appearing in Hollywood movies. The term “jitterbug” was introduced to the lexicon by a Cab Calloway song in 1932 and became the preferred term for young Lindy Hop dancers, ultimately becoming synonymous with the dance itself. By the time that LIFE magazine belatedly proclaimed the Lindy Hop to be "America's national folk dance" in 1943, the dance had been a part of cultural and social life in African American communities across the country for well over a decade.

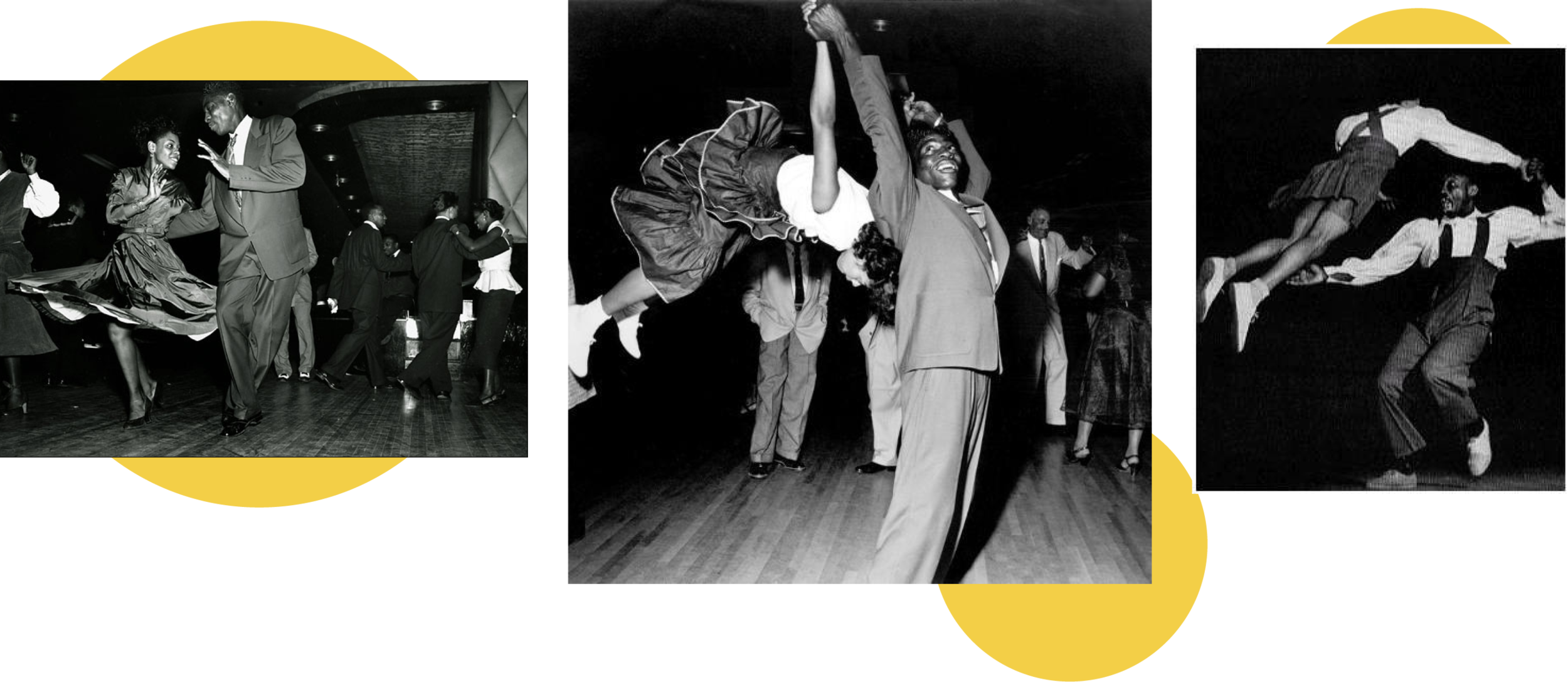

Dancers at the world famous Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, New York.

Today, Atlanta’s Lindy Hop dancers still flock to the Westside, to Ambient+ Studio, an old factory that has been converted to a hip event venue, art gallery, and production space. The Lindy Hop community here is still quite young, fueled by the youthful enthusiasm and athleticism of quirky students from nearby universities, as well as young, often single, professionals.

The Lindy Hop scene today is mostly white. The swing “revival” that occurred here — and everywhere — in the late 1990s and early 2000s brought swing back to the mainstream, but it did so in a way that was so decontextualized from its historic past that it was easy even for dancers to never learn about the historic roots of the dance. Many people still assume today that swing dance is a white-people thing. How could they not when Benny Goodman, not Fletcher Henderson, is considered the “King of Swing?”

The history that the contemporary swing dance community liked to tell is one of racial harmony and integration, but that was not true at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, where the dance began, and it was certainly not true in the American South. Jim Crow laws and segregation meant blacks and whites could not legally mix in social spaces, either on the dance floor or on the stage. Racial violence made it dangerous for black swing bands to tour and perform in the South. And many of Georgia’s greatest swing-era musicians left the South, with thousands of others, during the Great Migration.

Yet the city of Atlanta was a hub for African American entertainment in the South, at a time when African American music was — for the first time — the most popular music in the country. Several important venues here were a part of the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” a collection of performance venues throughout the Southeast and Midwest where it was safe for black musicians to perform during the days of Jim Crow. Atlanta was also unique at the time for its especially high concentration of venues owned and managed by black people. Several of these venues, including the Roof Garden and the Top Hat Club, were concentrated along Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue, which was just then hitting its peak as “the richest negro street in the world.” Looking back, it is hard to imagine that the story of swing in this city wasn’t a part of the story of how Atlanta ultimately became the hub of civil rights activism in the decades that followed.

The first reference I found to the Lindy Hop in the city of Atlanta is from March 1932 in the archives of the Atlanta Daily World. This influential black newspaper was founded just four years prior and was at the time the nation’s only daily newspaper written by and for black Americans. “Sam of Auburn Avenue,” a comedic society column detailing life in the city, was written by I.P. Reynolds Jr. “Himself,” the grandson of the formerly enslaved man after whom the neighborhood of Reynoldstown is named.

Reynolds recounted the scene at midnight on Auburn Avenue, then a bustling international business district. After an evening drinking bootleg liquor at a nearby speakeasy, a group of young people were lazing around a table in a chop suey restaurant, waiting for their late night grub. Someone put a coin in a self-playing piano and it pounded out, “I’ll Be Glad When You Are Dead, You Rascal You,” a song made famous by Louis Armstrong. When the song “goes to ‘getting good,’” a couple stands up and starts dancing, swinging out right there in the restaurant. “They give you just as pretty an execution of the ‘Lindy Hop’ as you would want to see,” Reynolds wrote. The scene was not unlike what you might see today at 2 a.m. at the pizzeria on Edgewood Avenue as the night owls try to sober up — except instead of hip hop, they danced to jazz.

“Well, let them dance if they can be happy,” Reynolds wrote, for "when the sun rises on the Easter horizon, that stark monster depression takes a blow at them and the specter of unemployment stares them in the face.” Crop failures in the 1920s and the bottoming out of the stock market had driven many to the Gate City. Atlanta in the early 20th century offered hope of a better life to the many rural laborers throughout the Southeast, but life was not easy. The Depression had exacerbated racial tensions. As black and white folks alike competed for the meager number of open jobs, white supremacist organizations used violence and intimidation to oust black workers from their jobs. Due to state and federal policies, many black people found they were excluded from public assistance programs. The desperation was very real.

But dance served as an escape. On any given night of the week, there were opportunities to swing out all over town. Countless dances were hosted by social clubs, collegiate fraternities and sororities, and civic groups. By 1932, Lucius Jones reported in his “Society Slants” column in the Atlanta Daily World that two-thirds of the regular dance crowd resided in the Westside neighborhoods and they called the Sunset Casino their home. There were also dances at the Roof Garden of the Odd Fellows Building on Auburn Avenue on the East side, performances at Bailey’s 81 Theatre on Decatur Street and in the City Auditorium in downtown, and dance contests at the Elks Club on Fort Street and in Washington Park.

The Roof Garden was considered perhaps the most respectable venue. The Odd Fellows Building was opened in a dedication ceremony led by Booker T. Washington in 1912. During the swing era, dances were held almost every night there on the roof, the sounds of swing audible up and down Sweet Auburn. In Living Atlanta, an oral history of the city published in 1990, B.B. Beamon, who was later a concert promoter in the city, said the Roof Garden was like a small club. “It featured a lot of local talent, like Graham Jackson, [J.] Neal Montgomery, Look Up Jones, the Ambassadors. It was lively. Nightlife, open air. Then, it was the place to go.”

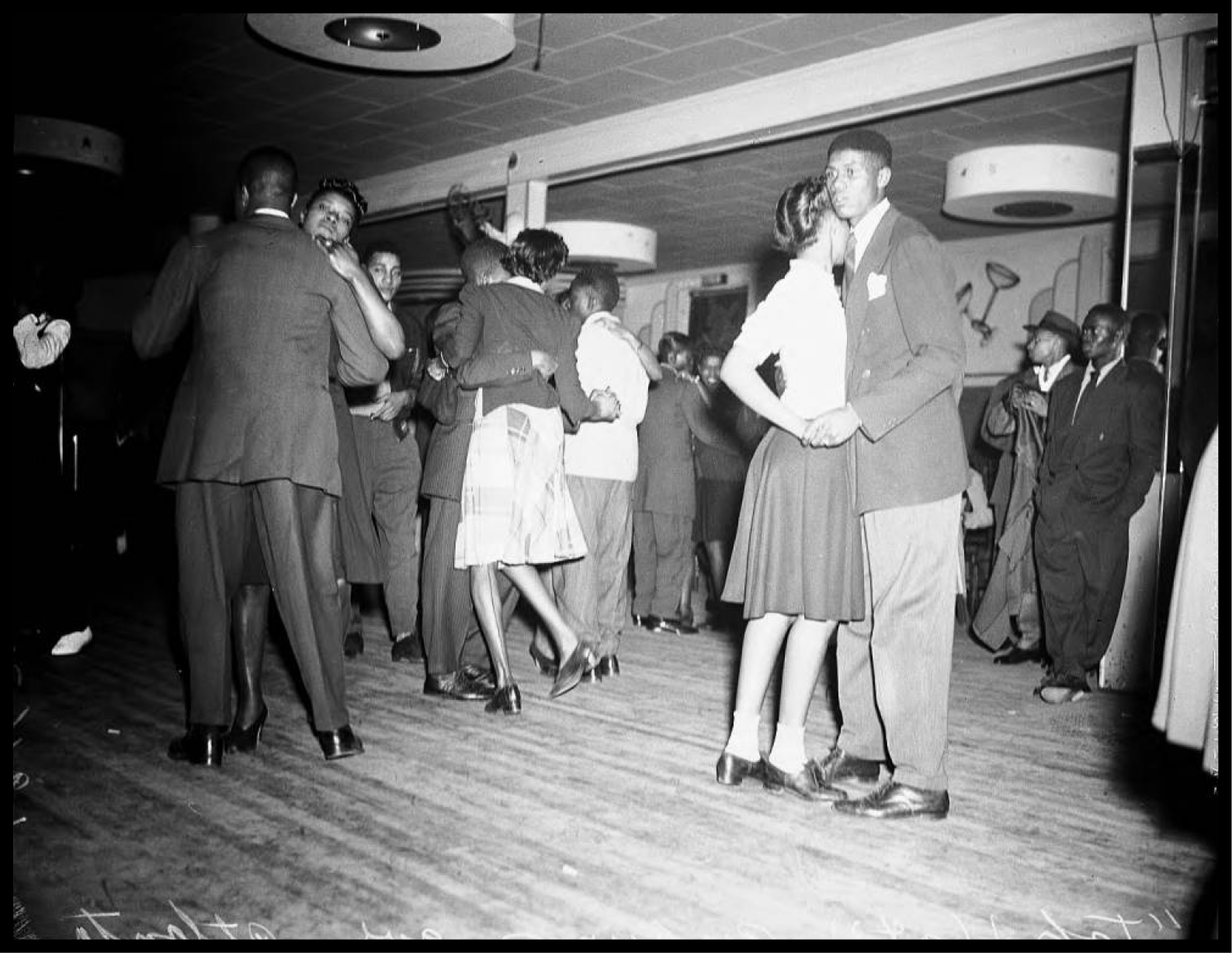

Dancing at the Top Hat Club in Atlanta, Georgia, 1943. Photo courtesy of Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition nationally in 1933, but the state of Georgia remained dry until 1935. Once the sale of liquor was again legal, the clubs along Auburn Avenue started to take off. The most important of these clubs was the Top Hat Club. Modeled after New York City’s Cotton Club, the 1,000-capacity “Club Beautiful” opened in May 1937 with a black-tie affair. The opening guest band was Andy Kirk and his Twelve Clouds of Joy with the incomparable Mary Lou Williams on the piano. The house band, the Top Hatters, held regular floor shows and regularly played to enthusiastic dance crowds.

The owners of the Top Hat were three African American businessmen: Lorimer Milton, Jesse B. Blayton, and Clayton R. Yates. Blayton had been Georgia’s first black certified public accountant, became the first owner of an African American radio station (WERD), and later was a major financial supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. Yates and Milton owned the thriving drugstore in the Odd Fellows Building a few blocks away. The year before, the same group had joined forces to reorganize Citizens Trust Bank, the first African American bank to join the Federal Reserve.

Newspaper clippings in the Atlanta Constitution promoting "White Night" at the Top Hat Club in Atlanta, Georgia, 1937. Reprinted with permission of The Atlanta Journal Constitution.

By the time the Top Hat opened, the swing craze had begun to spread among Atlanta’s white communities, too, and the owners sensed an opportunity: White Nights. Swing was the thing. But Jim Crow laws didn’t allow white patrons to enter the club under normal circumstances. One night a week the club opened for an audience of exclusively white clientele. According to Edwin Driskell, a local saxophonist in J. Neal Montgomery’s band, white nights featured “the same band, the same waiters, the same bartenders. The only difference was that Saturday night was reserved for white patrons.” Who paid a cover charge two-and-a-half times larger than the standard.

When nationally popular swing bands toured in Atlanta, they would play at the largest venue in town: City Auditorium. Owned and operated by the city, the Auditorium remained a strictly segregated space into the 1960s. When a black swing band came to town, as Lionel Hampton did with his band in 1942, there would be a special “section of seats reserved for white people as spectators.” As Driskell told it, “The whites could not dance. Blacks could dance. … In some instances, some of the activities that went on provided almost a show, watching them out on the floor."

Lionel Hampton and Dinah Washington perform at City Auditorium, ca 1942-1943. Panoramic photo taken from inside the whites-only section. Photo courtesy of the J. Neal Montgomery papers. Reprinted with permission of the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System.

Since the days of minstrel shows, and probably for much longer, white America had a twisted fascination with the art and music created by African Americans. They seemed to love the art and the confident assertion of humanity it represents, but abhor its creators. Swing, like so many other African American art forms before and since, was appropriated, repackaged, and sold for profit by white artists.

“A lot of the things that black people created and did back in the 20’s, 30’s, and 40’s, they never got credit for,” says H. Johnson, the incomparable disk jockey and music historian who hosts the “Jazz Classics” and “Blues Classics” shows on Atlanta NPR station WABE. “The black inventors or the ones who initiated it, their names go into obscurity. You don’t even know who they are because it’s been absorbed into the culture or it’s been just plain stolen.”

Even white artists who understood these injustices found it hard to avoid being complicit. Benny Goodman, the enormously popular Jewish band leader, didn’t come to perform in Atlanta until 1945, long after the popularity of swing had peaked. He had made the principled decision to play with only the best musicians, and his band was integrated. He was told he wouldn’t be able to play at City Auditorium if blacks and whites were together on stage. So he refused to come. He was already the most successful swing artist of the era, making so much money that he could afford to refuse to tour in the South.

What remains of these spaces today?

The Sunset was bought by B.B. Beamon in 1947, and he reimagined it as the Magnolia Ballroom. It continued to be an important performance venue during the era of R&B, and later as an important meeting place during the Civil Rights movement. Now, all that remains of this incredible history is the vacant lot.

The Odd Fellows building, which has been preserved as part of the Sweet Auburn National Historic District, was restored in 1988 and several attempts have since been made to reimagine this building as a lively space. Although the building still stands, right next to the highway overpass that cut Sweet Auburn in half in the 1950s, a full revitalization hasn’t yet succeeded.

The Top Hat Club was sold in 1949 to a groundbreaking woman named Carrie Cunningham, and it was reincarnated as the Royal Peacock. The club continued to be an important stop on the Chitlin’ Circuit during the era of soul and R&B, but as Auburn Avenue entered its decline, so too did the Peacock. True to the building’s musical history, the Royal Peacock is today a Caribbean-style nightclub.

Nothing remains of City Auditorium except the facade, which is now Georgia State’s Dahlberg Hall. The location once occupied by the cavernous auditorium space has been replaced, as so much of Atlanta’s history has been, by a parking garage.

H. Johnson, who has been DJ-ing on WABE-FM for over 40 years, also has a deep connection to the dance.

“My mother was something of an entertainer to an extent. She was not only a pianist, but she was a great Lindy Hopper,” he told me over the phone. As a child growing up in New Jersey, Johnson would watch his mother and her dance partner, a man named Emmett, dancing to records in their living room. “I remember my mother dancing something with Emmett. And then he would say, ‘Hey, let’s do this or let’s do that.’ … They were learning from each other. Inventing different dance steps was an art form.”

Johnson’s mother was supposed to try out for a group called Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, a professional group of swing dancers first organized in the late 1920s by Herbert White, the bouncer at the Savoy Ballroom in New York. Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers featured the best swing dancers in the world, including Al Minns, Leon James, Frankie Manning, and Norma Miller. They toured around the world in the 1930s and were featured in Hollywood movies, spreading the dance everywhere they went.

“My mother was supposed to be a part of that group, but someone came and fouled her career up. It was when she got pregnant with me,” Johnson said, chuckling. “It was my fault, I guess.”

Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, a professional group of swing dancers first organized in the late 1920s by Herbert White, the bouncer at the Savoy Ballroom in New York. Courtesy: New York Public Library

Johnson grew up steeped in jazz, blues, and gospel music.

“In my home, I was surrounded by entertainment. I mean, it was just there constantly.” Johnson’s grandmother was a cook and ran a restaurant out of her home in nearby Long Branch, New Jersey. While Johnson was just playing with his toys, local musicians and dancers would pass through to eat, socialize, and sometimes play on the family’s piano. Count Basie and members of his band were among the people who regularly enjoyed his grandmother’s home-cooked meals.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of him …,” Johnson said mischievously.

“Oh, I’ve definitely heard of him,” I said.

“I’m just being facetious. Everyone’s heard of Basie.”

Lindy hopping in Atlanta, Georgia. Probably a United Service Organization (USO) dance, 1943. Photo courtesy of Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Johnson moved to Atlanta in high school and quickly became swept up by the soul and R&B music that flourished in the city in the 1950s. He snuck into shows at the Royal Peacock on weeknights and emceed shows at the Magnolia Ballroom. But Johnson never learned the Lindy Hop.

“My mother never taught me how to Lindy Hop. Not because she didn’t want to,” he said. “She wanted to, but I didn’t want to learn.”

Over the years, the swing dance community has struggled with the question: How come black folks stopped dancing the Lindy Hop? The corollary, of course, is: How did it become so white?

When Patrick Manigault, a dancer in Atlanta since the late ’90s, once heard the question posed, and the response he heard was, “Well, we’ve been there and done that.”

“I don’t know if that’s a sufficient answer for me,” said Manigault, who is black. “There’s more to it than just that it’s been something that black culture did at some point.”

Once swing was mainstream, the commercially popular white bands became dominant. Swing music and jitterbugging lost its edge. Record labels, performance venues, dance studios, and the film industry were all controlled by white people, so it was difficult for black artists to attain the recognition and financial success of their white counterparts. Many of the most talented jazz musicians became more experimental, and their music more abstract in the late 1940s. In fact, bebop was intentionally undanceable, a direct response to the commodification and overwhelming whiteness of big-band swing. Around the same time, soul, R&B, and rock and roll music had started to take off.

Subsequent generations just didn't find it as cool to learn the Lindy Hop. Kids are “not going to take lessons for something that their grandmother would do in their living room,” said Taryn Newborne, a local dancer and vocalist who leads her own touring swing band on the national Lindy Hop circuit. And there was certainly no nostalgia for black Americans to relive this period in history.

“No matter what you see in the videos back in the ’40s,” said Manigault, “things weren’t great for black people then.”

But the music never died. Jazz evolved and was carried forward in Atlanta through events like the Atlanta Jazz Festival in Piedmont Park, still one of the largest free jazz festivals in the country. Ironically, though, this event rarely features vintage jazz or traditional big band swing. In fact, it is still rare for Atlanta’s most talented jazz musicians to play for dancers at all. They are often surprised to find out that there are still young people listening and dancing to swing music.

“Whenever I would bring the jazz musicians that I know to dances,” Newborne told me, “they would be like, ‘I had no idea this was here. There are people listening to jazz on purpose?’”

I told Breai Mason-Campbell the rumor that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been a jitterbugger, but she seemed skeptical. Mason-Campell is the founder of Guardian, an organization in Baltimore which seeks to preserve and restore culture and heritage by studying, teaching, and performing traditional African American dance styles like the Lindy Hop. I had just attended her workshop, “Race in Lindy Hop,” which she led at Lindy Focus, a massive dance event that takes place every New Year’s in Asheville, North Carolina. She told me her impression had always been that swing dancing and jazz music were viewed by the church-going crowd with hesitation. Jazz was associated with drinking, drugs, and sex. This was in conflict with the image of unimpeachable integrity that elite African American society was working hard to project as they pushed for equality.

However, the impression I gleaned from the pages of the Atlanta Daily World is that swing was fully embraced by Atlanta’s black residents. When Fletcher Henderson performed in Atlanta, for example, he was welcomed back as a hometown hero. Henderson was a native Georgian and a graduate of Atlanta University, the nation’s first institution to award graduate degrees to African Americans. He had become an extremely influential arranger and band leader, playing a central role in the development of the sound of big band swing. An advertisement in the Atlanta Daily World for Henderson’s 1936 show at the Sunset Casino proudly proclaimed him the first African American to draw a five figure paycheck. “And now he comes as a pioneer; the master exponent of Modern Swing Music.”

Fletcher Henderson & His Orchestra played in 1935 at the first Harvest Moon Ball, a massive amateur dance competition held annually at Madison Square Garden in New York City. That first Harvest Moon Ball was won by Lindy Hoppers from the Savoy who broke many of the contest’s rules by breaking away and throwing aerials. Archival footage from the Harvest Moon Ball is still watched with awe by Lindy Hoppers seeking inspiration today.

Gravity defying moves by dancers at the Savoy Ballroom.

A year later, in December 1936, Atlanta put on its own version of the Harvest Moon Ball. The contest in Atlanta was sponsored by the Youth Movement of the NAACP, with the goal of “raising funds with which to fight the injustices and brutality shown Negroes of this city.” An article in the Atlanta Daily World encouraged civic-minded members of the black community, even those who weren’t normally the type to attend the city's nightclub attractions, to “show their democracy and public-spiritedness” by purchasing tickets. An estimated 1,000 Atlantans attended the Ball at the Sunset Casino. The contest was emceed by the prominent black physician Dr. E.G. Bowden, the same man who had delivered the infant Martin Luther King Jr. seven years earlier.

Dances were also held at “Atlanta’s Black City Hall,” the Butler Street YMCA. The Butler Street Y was home to numerous organizations in the city, including the Atlanta Negro Voters League. Most other places were closed to them, so the Butler YMCA was at the center of recreational life for the city’s black youth. There, they could safely relax, swim, play basketball, shoot pool, and do arts and crafts.

In the early 1940s, however, the Atlanta Baptist Ministers Union, an association of black ministers, became concerned about the dances held at the ‘Y’ and voted to study them. According to a book about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s faith journey, King’s father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., was a member of both the executive committee of the Butler Street YMCA and the ministerial association. He was delegated to go observe a dance and make a recommendation to the group of ministers. The Rev. King stayed for about forty minutes, watching nearly 400 young people doing the jitterbug. As he left, King said to Dr. Warren Cochrane, the director of the Butler YMCA: “I don’t approve of dancing and I don’t let my children dance. But I suppose it is what the kids want to do.” He decided not to recommend a censure of the dances, and the ministerial association agreed to continue its financial support the YMCA.

Of course, the elder Rev. King’s own children danced. King Jr. once confided to Cochrane, “I sneak into your dances sometimes.” Indeed, according to his brother, the teenage Martin Luther King Jr. was “just about the best jitterbug in town.”

Swing music and dances like the Lindy Hop confidently, boldly embodied freedom. Swing’s success as an unstoppable worldwide phenomenon no doubt contributed to the sense that the continued oppression and disenfranchisement of black people was intolerable. Many of the very same spaces that held dances during the swing era served new roles as important meeting spaces during the Civil Rights Movement. And countless people who had been jitterbugs in their youth, just like Dr. King, grew up to dedicate their lives to civil rights activism.

Starting in the 1990s, swing dancing surged back into the mainstream culture. According to Bobby White, now an internationally recognized dance instructor in New York City, Atlanta had a large and enthusiastic swing scene during the 1990s, as did all major American cities. Patrick Manigault remembers being dragged to a swing dance at the Masquerade when he was a graduate student at Georgia Tech and getting hooked. The crowds were large enough then to sometimes take over all three levels (Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory) of the grungy alternative rock venue, then located in the old Dupree’s Excelsior Mill in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward. But as was true across the country, almost everyone at these events danced a style of swing called “East Coast Swing.” And they were overwhelmingly white.

East Coast is a very simple six-count dance. Step, step, rock step. You can learn the basic moves and be out on the dance floor with a quick 30-minute lesson. Today, almost every swing dance instructor teaches East Coast Swing during the beginner’s lesson, hoping that it will be enough to whet the appetite of the new dancers and keep them coming back for more. Back in the 1940s, when swing became a part of mainstream culture, there was a huge demand to teach the dances that accompanied big band music. The Lindy Hop was deemed too difficult to teach to beginners, so a white ballroom dance instructor named Arthur Murray modified the complex, eight-count Lindy Hop and created the easier East Coast Swing.

Murray had first started teaching dance by mail-order in 1912, but his business flopped. In 1919, he came to Atlanta to study business administration at Georgia Tech. While a student there, he famously arranged to have live music transmitted over the radio from the Georgia Tech campus to 150 of his dance students on the roof of the Capital City Club in downtown Atlanta — the first radio broadcast of live music for dancers. Murray later returned to New York, eventually opening a dance studio in the late 1930s. His stint in Atlanta pre-dated the swing era, but Murray’s business acumen was honed here. His commodified East Coast Swing was taught across the country in his franchised dance studios, hotel ballrooms, and even on cruise ships. He is considered today one of the most successful dance instructors of all time.

It was due to the success of white swing-dance instructors like Arthur Murray that, at the height of the neo-swing craze in the ’90s, Lindy Hop and the people who created it were erased from the mainstream narrative of swing. East Coast was often the only dance taught, and few people knew anything else existed. The black dancers who had invented and innovated the Lindy Hop were never able to establish similarly successful careers as professional dancers or instructors.

Fortunately, the nationwide neo-swing craze sparked the curiosity of at least some dancers, who started digging into swing’s true history. A few surviving members of the original Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers had begun teaching the Lindy Hop again in the mid-1980s, sparking enthusiastic followings in New York City, Los Angeles, and Sweden (of all places). These original Savoy Lindy Hoppers eventually became veritable celebrities among the community of swing dancers that blossomed around that time. Starting in the ’90s, dancers traveled from all over the world to take Lindy Hop workshops from people like Frankie Manning, and eventually Lindy Hop scenes popped up all across the globe.

By about 2002, there was a large community of Lindy Hoppers in Atlanta. There was also a group of East Coast swing dancers who never learned Lindy Hop, and according to Bobby White, “sometimes there was a rift between the two groups.” By the early 2000s, the neo-swing fad had faded. The weekly swing dances migrated to a hotel ballroom at the Perimeter of Atlanta hosted by DJ Alan White, a professional radio DJ and an early innovator of internet radio. The Lindy Hoppers desperately wanted to swing out to classic swing-era jazz, but the DJ insisted on playing a mixture of rockabilly, big band, and party music.

“We had started to educate ourselves on the history of the dance,” said Michelle Chaff, a dancer in Atlanta since 1999. “It just didn’t match what Alan was putting on.”

Michelle and another dancer, Nima Farsinejad, approached Bobby White, and they hatched a plan. They decided to start an event — by and for dancers — where Lindy Hoppers could swing out all night long. Atlanta’s Hot Jam was founded in February 2005. The group rented out the Garden Hills Community Center in Atlanta’s Buckhead neighborhood for Monday nights. The little “cabin in the woods,” with its beautiful hardwood floors, became the home of Atlanta’s Lindy Hop community for over a decade.

During this period, Atlanta’s swing community began to flourish, and Atlanta quickly became the major swing dance hub in the Southeast.

“That’s when everyone in the Lindy hop scene was really close and willing to try to make stuff happen,” said White. Atlanta hosted a number of large weekend events, which drew Lindy Hoppers from across the country. Atlanta also had two performing dance troupes: Big George and Tiny Bunch. For many, Lindy Hop became all-consuming.

“Lindy hop for me became my social circle,” said Manigault. "It became my hobby, it became my source of exercise, it became a source of, certainly, joy and a way to meet people and learn about people and other places.”

Swing dancers at Atlanta’s Hot Jam. Photos by Kanwei Li

One event that holds a special place in many Atlanta dancers’ heart is Swing and Soul Weekend. First organized in 2007 by Tena Morales-Armstrong along with Manu Smith and Peter Strom, the goal of the annual event was to bring Lindy Hoppers from across the country to Atlanta to engage directly with active, thriving black dance communities. There were workshops on hand dancing, Chicago Steppin’, pop and lock, and the Wobble. There were also talks by local musicians and historians of Motown and soul. Huge trays of food were prepared by volunteers in the kitchen and served buffet-style: collard greens, chicken, waffles, and macaroni and cheese.

“It was like eating your mom’s home cooking,” Newborne said. “The spirit of it … everybody just felt so welcomed. It just felt like their soul was satisfied.”

The reliability and consistency of Hot Jam fueled the dance community in Atlanta. At the core of the event was the commitment to the history of the dance, to playing real classic swing music, to teaching the original dance forms and choreographies, and to creating a welcoming, friendly environment. The weekly dance started to thrive financially, and they started to bring in live musicians. At first, this was only during the annual holiday dances, but by the time I moved to Atlanta in 2015, you could expect live swing bands once a month. That’s when the neighbors started to complain.

“It was live music that did us in,” Chaff said with a sigh. The wealthy Buckhead community became frustrated with the noise and the large number of cars parked on the street. To be clear, Lindy Hoppers today are mostly just a bunch of nerds who like listening to old-timey music.

“We are pretty much the last people who would vandalize something,” said Cari Westbrook, who now serves on the Hot Jam board. Unfortunately for us, the guy that lived across the street apparently had some kind of pull with the city. After one particularly raucous night in 2017 which featured a traditional jazz band from Huntsville, Alabama, the neighbors decided they had had enough. Hot Jam was kicked out of the venue where we had been dancing every week for 12 years.

“But there’s sort of a beauty in that,” Chaff said. “We brought so much energy and so many people to that little cabin, and it was just too much to contain it.”

We have since settled into our home at Ambient+ Studio on the Westside. Sometimes attendees complain that Ambient+ is too far from where they live in the suburbs or that it’s in a "bad neighborhood." It’s definitely always too hot inside the room. The air conditioner struggles to keep up with the heat generated by the nearly 100 dancers who come out each Monday night. Yet in so many ways it feels just right. This move has brought us closer to the roots of the Lindy Hop in our city. We no longer fear complaints about noise. And, frankly, it’s kind of cool for the Lindy Hop to be, once again, more squarely at the center of Atlanta’s innovative arts and music scene.

Earlier this year, as happens on occasion, there was some production happening in another one of the studio spaces during our Monday night dance. To be blunt, the whole building smelled of weed. I happened to be DJ-ing so I decided to have fun with it and threw a bunch of classic reefer songs into my set (it’s truly a genre unto itself). As I was leaving for the night, one of the Hot Jam organizers giddily told me that Offset was in the building, filming the music video for Kiana Ledé’s “Bouncin’.” They had rolled the stripper poles out of our studio space just before we began the beginner swing lesson.

Over the last few years, Lindy Hop dancers on a national and sometimes international scale have begun the difficult process of reckoning with the issue of race within the dance. We have thought more carefully about how we can create a welcoming and inclusive dance community. We are working to educate ourselves and our fellow dancers about the historical roots of Lindy Hop. According to Cari Westbrook, the broader Lindy Hop community has finally “started to be really intentional about leaning into the mistakes that we made and fixing them.”

Everyone I spoke to said that since the founding of Hot Jam, Atlanta has had a particularly welcoming scene. Back during the swing resurgence in the late 1990s, Atlanta did have a relatively high-concentration of black dancers compared to elsewhere.

"There were more than zero," said Javier Johnson, who started dancing in Atlanta in the early 2000s. "I wouldn’t say that it was overwhelmingly African American. But there were definitely role models there.”

“They just wanted more people to dance with,” said Taryn Newborne. “And so they felt like if you improved, they got to have fun dances.”

Black dancers obviously noticed, though, that they were rare at Lindy Hop events.

“At any given dance, all the black people would know each other,” said Johnson. He then proceeded to name the black Lindy Hop dancers he knew in cities across the Southeast. “We all kind of know each other, which means there’s not enough of us.”

Especially when traveling, Newborne noticed that she sometimes would not get asked to dance, even when she was recognizable as a volunteer at the event or a performer on stage. This is still an all-too common experience, unfortunately.

“An inclusive community is a community where we choose to dance with anyone,” Westbrook said. “I hope that we’re moving towards a space that is inclusive on all fronts and thinking about ageism, ability, body type, or gender presentation. All of it.”

In Atlanta, following the lead of other communities around the country, we are working to implement practical strategies for making our dances more welcoming for all people.

Poster for a dance contest at the Savoy Ballroom

“One of the key differences between appropriation and appreciation is understanding the historical background of what we’re doing,” Westbrook said. So we talk about the history of the dance in every beginner’s lesson. One of our many instructors, Jamica Zion, put together a poster board depicting the history of Lindy Hop, telling the story of the original dancers at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom. We display it every week by the water jugs, so dancers can learn some history while they are taking a break and rehydrating. Hot Jam’s leadership has also challenged DJs not only to play traditional swing music from the 1930s and ’40s, but to take the time during our sets to talk about the artists and their lives. For Black History Month last February, we each spotlighted an African American artist. And we are doing something similar for October, which is LGBTQ+ history month. We intentionally use gender-neutral terms like ‘lead’ and ‘follow’ when teaching the dance. And we model verbal consent when asking someone to dance during the beginner lesson.

In other words, Lindy Hop is slowly becoming “woke.” Or, perhaps more accurately, reawakened.

Swing dancers at Atlanta’s Hot Jam. Photos by Kanwei Li

The Lindy Hop — this dance that we love — was born at a time when its inventors were cruelly and systematically excluded from full participation in our democracy, both here in the South and elsewhere. The Lindy Hop may have been invented in Harlem, but it has deep roots here. The irony and injustice of Jim Crow, particularly with respect to swing, is that some of the most extreme violence and oppression was imposed on black people, just as the music that they created became a worldwide sensation. That this history has somehow been lost, that the dance has been so whitewashed, is to our great shame.

Until recently, modern swing dancing was thought of as an activity people would do to feel nostalgic, where people could wear vintage clothing and pine for the good old days. But “the reality of it is that the dance itself was progressive,” Patrick Manigault said.

These art forms intentionally and consciously pushed back against an unjust system of oppression. Swing music and the Lindy Hop were undeniable, confident assertions of a belief in the possibilities of freedom. To dance to that music was itself an act of resistance. The groundshaking cultural phenomenon of swing was so powerful that it had made it impossible to continue to ignore the humanity of black people and to abide the injustices of Jim Crow.

That’s the true legacy, and we must acknowledge it as we dance the Lindy Hop today — each and every time we swing out.

Dr. Nicole M. Baran is a postdoctoral researcher in neuroscience. She received her undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. in Psychology from Cornell University. Originally from Wheat Ridge, Colorado, she moved to Atlanta in 2015 to begin research at Georgia Tech. She currently works at Emory University, studying the genetic basis of social behavior in songbirds. She has previously written for Nautilus Magazine and Scientific American. She has been swing dancing — for fun — for more than 15 years.

Header Photo: "Dancing at the Top Hat Club in Atlanta, Georgia, 1943. Photo courtesy of Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library."