Sometimes, bands and cities weave themselves together, their music summoning memories of special times in special places. So when Charleston’s beloved Jump, Little Children reunited last year in the wake of the massacre at Emanuel AME — after 10 years apart — they helped their hometown wrestle with a question they had posed on their first album back in 1998: What, exactly, is home?

“In the cathedrals of New York and Rome, there is a feeling that you should just go home, and spend a lifetime finding out just where that is.”

— “Cathedrals”

Jump, Little Children | Charleston, South Carolina

Story by Adam Kincaid | Photographs by Nathan Baerreis

The reunion tour for the most beloved band Charleston ever produced might never have happened if not for the darkest hour in the city’s modern history. By the time the curtain dropped on their final show, each of us — the band, and me, and the city we both love — would never be the same.

It all started when a cryptic website (churchandqueen.com) appeared in March of 2015, featuring little more than a clock counting backward. It was a countdown: 291 days, 18 hours, 41 minutes, nine seconds. Eight seconds. Seven. Ticking toward a zero that would arrive Dec. 28, 2015.

The digital countdown would not be news but for the rumors that the site was advance marketing for a soon-to-be announced Jump, Little Children reunion show. It had been a decade since their last performance, a 2005 concert later released as the now out-of-print “Live at the Dock Street Theatre,” named for the iconic venue where it was recorded.

Dock Street is a national landmark that sits at intersection of Church and Queen (once called Dock Street) streets. It played host to a decade-long annual series of Jump, Little Children acoustic concerts.

The rumors were confirmed in May, and by the time tickets to last year’s reunion show went on sale, the news broke that the show would be acoustic, in keeping with the old tradition. A second show was added in anticipation of demand. Both nights sold out in exactly two minutes. Days later, seven additional concerts were added: two more shows in Charleston at the larger Music Farm, two shows in Atlanta, a stop in Nashville, another in Greenville, South Carolina, and one more in Columbia. When those tickets went on sale, they too sold out immediately and began trading on secondary markets for more than $300 each. They’d seen the Dock Street demand coming, but the demand throughout the South surprised everyone and was the talk of Charleston throughout the early summer.

Or it was, until June 17, when headlines around the country read “Breaking news: nine killed, three wounded in ‘hate crime’ attack, Charleston, S.C.”

The shooting was at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church on Calhoun Street. A Lexington, South Carolina, man allegedly walked into the church and methodically massacred senior pastor and Rev. Clementa Pinckney — a state senator and one of the pillars of the Charleston community — and eight others, leaving three more wounded but alive to tell of the carnage. The churchgoers were conducting a prayer group when they were chosen by the shooter as kindling for the fires of the race war he believed he would ignite. He understood the ghosts that haunt the city; he thought they’d help him burn the whole thing down.

As media from all corners of the nation converged on the corner of Calhoun and Meeting streets in the hours after the killings, cameras trained on the families of victims still lying dead in the church basement. Then, those families schooled the nation on strength and courage under fire. They stood in the face of their greatest adversity and spoke with the media about forgiveness. Behind them the white spire atop the Emanuel AME church steeple arched up from its perch on Calhoun Street to announce that this was indeed the Holy City.

In the wake of the racially motivated mass execution, thousands descended on Charleston. A bridge walk was organized; a single, unbroken #unitychaincharleston as the hashtag went. Among those who walked that bridge were the still-local alumni of Jump, Little Children — bandmates Jay Clifford and Johnathan Gray. It seemed like all of Charleston was there — the sons and daughters of victims, side by side with the owners of shops uptown and down, the ministers of churches black and white, the descendants of slaves and the inheritors of Old South money, and those guys from Jump, Little Children — whose music had woven itself into the fabric of Charleston — all walked across that bridge together.

There would be no race war. The planners of the unity event at Ravenel Bridge expected 3,000 attendees. More than 10,000 arrived to reclaim the spiritual high ground for the low country.

It was a pivotal and cathartic moment for the city. It would be six more months before I’d get back to Charleston to see for myself, and I’d be there with the reunited members of Jump, Little Children. Though I’d come to cover a concert, I would leave with a new understanding of what community resolve looks like in action, how not to ask the mayor’s office for an interview, and a whole lot more about how the city’s favorite sons, in losing their youthful dreams of fame, found out just where home is.

Race, as one might guess, has always been at the heart of the Charleston experience.

The location of Emanuel AME church — on Calhoun Street — is a sad irony. The avenue is named for John C. Calhoun, vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832, who was perhaps the most openly racist American public figure of all time. He argued on the Senate floor that human enslavement was not a “necessary evil,” but rather a “a positive good.” For Calhoun, it was a God-given right legitimized by the supremacy of the white man. He believed he had every right under God to enslave others and beat them into the submission required to tend his lands. His plantation land is now the campus of Clemson University.

It wasn’t just Calhoun, of course. In the words of Charleston’s daily Post & Courier, the city was “ground zero” for slavery in America. Nearly 40 percent of all the slaves brought to America began their lives of bondage on Sullivan’s Island.

To memorialize the sad fact that so many victims of oppression were brought to her sands, Sullivan’s Island has done … nothing at all. To this very day, the only memorial of any kind is an inscribed bench donated by author Toni Morrison. There is nothing else publicly displayed on the island to honor the sacrifice of those who came ashore against their will.

By the time I made Charleston my home 15 years ago, things were improving. In the time of Jump, Little Children , Charleston was burgeoning. Mayor Joe Riley, whose 40 years in office ended in January of 2016, had reawakened the city from its decades of slumber to address, as the 1980s and ’90s progressed, many of its longstanding problems.

When it comes to the reinvigoration of any city, musicians are like canaries in the coal mine. They have more developed noses to sniff out a town’s buzz. A future economic study could probably track the migratory patterns of up-and-coming musicians to help identify the peaking economies of the following decade. Don’t believe me? See: Nashville present; Seattle, circa Nirvana and Pearl Jam; Atlanta in the wake of Outkast’s rise.

Charleston too broke a few famous bands while it economically exploded. It was the era of Hootie and the Blowfish and Jump, Little Children. In the early 1990s, the city was just the sort of up-and-coming, seaside paradise a young, upstart band of ragtag musicians from a Winston-Salem art college might want to call home. Moving to Charleston was the choice that gained JLC its fame. Local DJ Dave Rossi had taken a liking to the band, and allowed them to record a few tracks in his studio. Those songs became a demo that resulted in a record deal and the release of 1998’s “Magazine.”

Check out this review, in all its accurate glory, from A.V. Club, which summarized how out of place JLC was in its era: more precursor to Vampire Weekend than contemporary to Hootie, whom they subtly (and hilariously) annihilate:

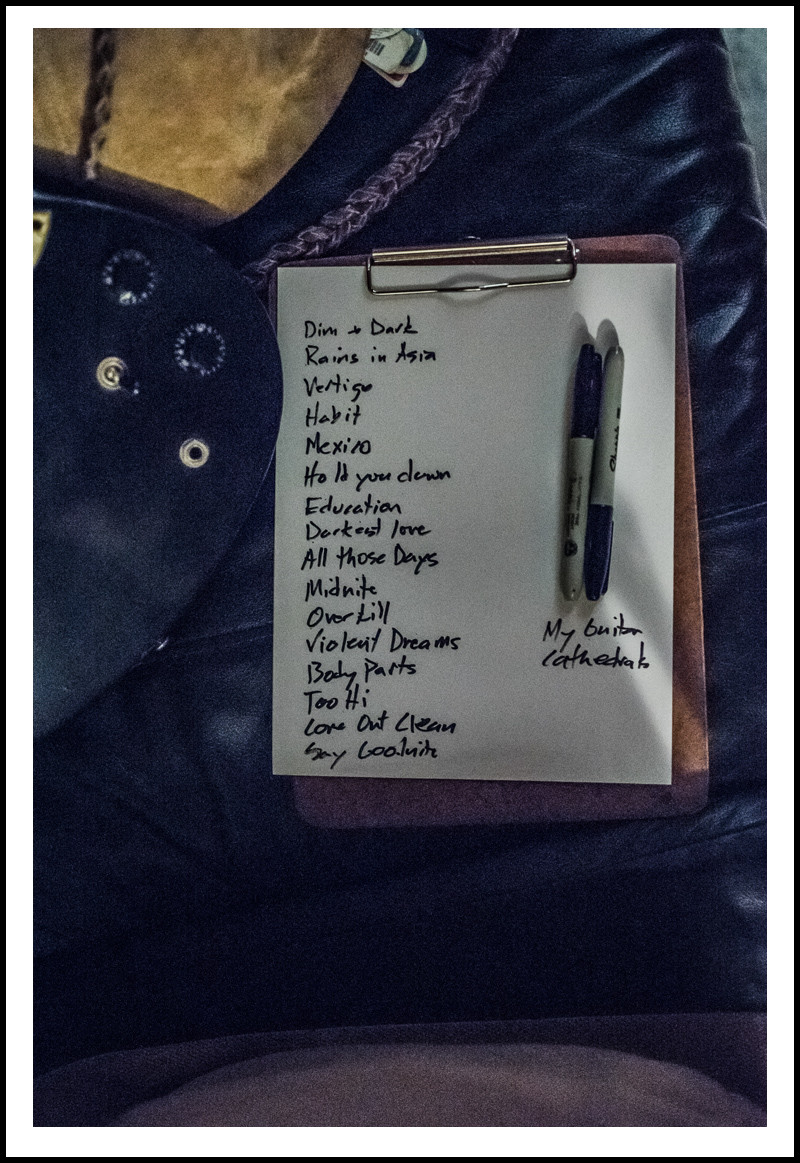

“Jump, Little Children steps out of the gate with a whole bunch of strikes against it. The South Carolina band is a Friend Of Hootie — recording for the group's vanity-label imprint, Breaking Records — at a time when Hootie's star is fading into oblivion. Its debut record, ‘Magazine,’ has been released with virtually no fanfare, reviews or promotional muscle. The band's name sounds like an album title, while the title of its album sounds like (and, in fact, is) the name of a band. But if Jump, Little Children doesn't catch on, it'll be a shame: ‘Magazine’ is a fine debut, with far more gems than misfires. Singer Jay Clifford's smooth, engaging tenor allows the album's best material to transcend Better Than Ezra-style blandness, while subtly applied cellos and accordions add critical instrumental depth. Consequently, for every Third Eye Blind-esque "na-na-na" chorus ("Not Today"), shrill goof ("Body Parts") or poetry reading ("Habit"), there's at least one magnificently hooky, guilty-pleasure pop-rock single ("Violent Dreams," "Come Out Clean") or sweetly sung ballad ("Cathedrals," the gorgeous album-closer "Close Your Eyes"). A cutout-bin classic in waiting, ‘Magazine’ deserves to be heard while the group can still draw royalties from it.”

Of course, that review and all the others would never have been written were it not for the biggest break JLC ever landed, when “Cathedrals” caught the ear of alternative radio tastemaker Leslie Fram. She was the morning radio host and — more importantly — program director at 99x, the iconic alt-rock station in Atlanta throughout the ’90s. One could argue Fram was the most influential person in the Southern radio landscape of the era.

Fram introduced me and a generation of ’90s Atlanta kids to the bands that defined our youth. She was among the earliest supporters of Jump, Little Children and their oft-teased but fully profitable Charleston brethren Hootie and the Blowfish.

"I heard ‘Cathedrals’ on a trip to Augusta; Dave Rossi had been playing them in Charleston and I just fell in love,” she says. “Still in love with Jump today. ‘Cathedrals’ is one of my favorite songs.”

She wasn’t alone in that sentiment. Fram remembers a time she played “Cathedrals” on the air at 99x, prompting sometimes-Atlanta-resident Elton John to call her on the studio’s request line and ask whom he’d just heard. Even this publication named Ruby Amanfu’s cover of “Cathedrals” among last year’s top tracks. And rightly so. The song is timeless. It’s as if it always existed, somewhere in the heavens.

Today, Fram lives (where else?) in Nashville, and is the senior vice president of music and talent for CMT. The hybridized folk-country-bluegrass-Americana of the day is a soup that Leslie Fram simmers and spices. Where once she made the soundtrack for ’90s rock in Atlanta, now she influences the alternative country so representative of the cultural renaissance happening in Tennessee.

“Listen, if you’re here in Nashville and we like your records, we can get you some exposure,” she said with a laugh, dismissing my clumsy attempt to plumb the depths of her star-making power.

But make no mistake: Fram is and has long been the boss. And so the fact that she loved Jump, Little Children from the moment she stumbled upon them was good news for the band.

It probably didn’t hurt that they buttered her up by bringing her a painting by Lamar Sorrento, the folk artist who’d created the album cover for “Magazine.” The band had heard she loved folk art, and so they brought a one-of-a-kind for her. It still hangs in her home today.

All that love from Fram and others started getting JLC national airplay for "Cathedrals."

In 2005, I was putting the finishing touches on my victory-lap year of undergraduate studies, and was in Italy for a semester abroad. I hadn’t even thought about Jump, Little Children for a while, until I visited Leonardo Da Vinci's “The Last Supper” at the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. The moment I entered that room — sparse and undecorated save for the fresco of Jesus and his disciples painted across the expanse of one wall, the lights in the room blackened except those needed to illuminate the work — I was floored. The painting is so impossibly masterful, so ancient and mystic, so forthright in its own achievement of perfection that I could do nothing but stand there staring at it, all too aware of my own inabilities in contrast.

Then I remembered the lyric. “In the cathedrals of New York and Rome, there is a feeling that you should just go home.”

Yep. Agreed.

After “Magazine” was released in 1998, JLC toured, crisscrossing America and thinking about the follow-up album. They were, by the time the tour concluded, a whole lot more famous than they were rich from their success with “Magazine.” With musicians, just like pro athletes, the real money gets made on those veteran contracts.

When they finally returned to Charleston, it was to record a second studio album, 2001’s “Vertigo.” If in naming the album they were considering their own footing in the world of music, then the title was perfect. Their label, Breaking Records, had been cut loose by parent company Atlantic.

And then everything was fucked. “Vertigo” sat on a shelf at the de-funded Breaking Records as the band battled for the rights to its music. Lawyers and courts. Suits and ties, briefcases and obtuse letters written in the formal legal tongue of obfuscation by parsed detail. Pleated pants, man. That guy was wearing pleated pants, and he was dead serious, too.

In the end, Jump, Little Children did win the rights to “Vertigo,” and all it cost them was a year, all the money they’d ever really earned and the backing of any label at all. But damn it, they owned their own work. A friend of the band suggested to me over drinks at a JLC after-party in Charleston that maybe, in retrospect, they could have just recorded 10 different songs and released something while the iron was still hot; after all, if they won in court in the meantime, they could still release “Vertigo” later on, and it would have kept them on the media radar and saved them the year spent in court without an album (or a label). But that isn’t what happened, and I’ve lived enough years to say confidently that “maybe shoulda” doesn’t mean much.

To make matters worse, “Vertigo” was finally scheduled for release on September 11, 2001. Not the best day for an album debut. They waited a couple more weeks for a formal release, hoping to avoid being consumed in the historic gray clouds that have covered so much of our world ever since.

“Vertigo” eventually took hold, to some lesser degree; one track was featured on the TV show “Party of Five,” an achievement that still outpaces the height of my professional accomplishments. The album also reached No. 44 on the Billboard Independent Albums chart, which is not the same thing as the Billboard 200, but rather the top albums released and sold via independent distribution. It was a full three years later before the next album, 2004’s critically acclaimed but publicly underappreciated “Between the Dim and the Dark.” It, like the album that preceded it, had come too late. The glossy sheen of “Magazine” had faded.

Eventually, Jump, Little Children just “ran out of gas,” in the words of Matt Bivins, who played accordion, harmonica and mandolin for the band. And so, at the 2005 annual Dock Street Theatre acoustic show, they finished their set, and Matt’s brother — drummer Evan Bivins (a man I genuinely grew to like during my time with the band) — announced to the most faithful JLC fans, “Tonight was our last show.” It was something they had mutually decided as they ground their way through the tour leading up to that show.

In the years after, the Bivins brothers moved to Chicago, while cellist Ward Williams headed to New York. Bass player Johnathan Gray stayed in Charleston and basically just kept doing his thing, as did vocalist and guitarist Jay Clifford. Clifford pursued a solo career and poured himself into his newly established family — more a soccer coach than a rock star.

For fans of the band, it was over. The day had come where the sun didn’t rise.

Then, last year, that mysterious website appeared.

I caught the middle part of the band’s wild ride when I arrived as a freshman at the College of Charleston in 2001. Regional radio airplay had catapulted Jump, Little Children onto the national stage, but we were neighbors living on the same block of Coming Street, although we never got to know each other.

At the time, they were the most famous people (save for the reclusive Bill Murray) in our little town on the rise. In 2002, , an old friend popped into town with an extra ticket to a JLC show at the Music Farm. As we walked back home afterwards, I wondered which of the houses was theirs. I’d been wondering that for a long time. My intent to crash what I imagined would be a raging after-party.

Last year, I told Evan Bivins that story. He said College Me would’ve been disappointed.

“We were band nerds,” he said Evan. “Art-school kids. It really wasn’t very cool. College You would be disappointed.”

He was wrong, because Adult Me still is a little disappointed at all that.

For 15 years, I’d held onto an idea of the famous, mysterious neighbors who’d proven difficult to identify. Like an elusive game of cat and mouse. So it was funny to meet the actual people. These five guys, they were sincere. They were real. They carried with them the same heaviness I do, that anyone would, for all the ways we missed moments of life, all the doubts that just kind of stick around no matter how famous you get. They weren’t rock stars; they were people — and frankly, a bunch of big ol’ softies.

Matthew Bivins, the pixie-like multi-instrumentalist who impressively played the reunion tour with a collapsed lung, told me, “Now, we’ll be Jump, Little Children because we want to be, not because have to be.”

I walked around Charleston with the band as their final Dock Street shows approached, talking about life and expectations, desires and plans. As we walked north on Church Street toward the famous Charleston Market, it was pretty clear I was walking with the most famous men in Charleston that day. We’d make it a couple dozen feet, and our little entourage (complete with our backwards-walking photographer) had been stopped by several people to thank the guys for this or that. When we ducked into the cemetery at St. Phillip’s Church, just a block up from the theatre, we found more peace and quiet — and some gravestones to sit on — while we finished talking. Before we parted, we realized that the opulent grave we’d selected as a perch belonged to none other than that old racist vice president of ours, Charleston’s one and only John C. Calhoun.

Before the last show at Dock Street last year, I spoke with a Charleston police officer about the city in the time since the shooting.

“To be honest we didn’t know what was gonna come after,” he said. “But for the most part, everyone here has probably been even more aware of each other. More helpful. It’s been all the little things, you know? Shows like this, local guys, they help. And anything else that people get together about. Guys are looking out for each other because they’re from Charleston, not because of race or whatever else. Just a million little decisions people make around town now.”

It was good to hear.

When the band took the stage for that last show — and again when they left — people cheered and cheered. Not me. I just smiled, because the crowd was loud enough. I just cared that five guys I’d gotten to know over the course of December had smiled deeply, watery pressure behind their eyes, daring them to release the tears of accomplishment and joy that can be had only when earned.

“This tour, the fans — it was all just such a gift,” Clifford told me. “We feel like we received this amazing gift. My son got to see me as the lead singer for Jump, Little Children, you know? Until now, he’s only ever seen me as the soccer-coach dad. Same one they’ve always known. But when we played our first show, the look on my son’s face was one of the most powerful and moving things I’ve ever experienced.”

I’d thought I was there to write about a band, and ’90s nostalgia, and maybe the shootings. But the story really wasn’t about any of that. At least not the good story.

It was more about coming to terms with life’s winding struggles, the fleeting successes that come and go with the wind, the endless hope for better and the ice-cold realization that there is no such thing as better in this world, just different. In the end, it’s not our destination, but how we feel while on the path, that makes us or breaks us. All of Charleston understood that in the aftermath of the Emanuel massacre. I now understood it, too: The path is all there is.

Just the path, the people who travel it and the things that sent them on their way. The dreams that didn’t come true, no matter how much everyone wanted them to, and the ways in which that’s OK, too. Ten years after their breakup, Jump, Little Children’s members found new joy — and anyway, you can’t have a reunion without some time apart. They got to experience anew the rush of a crowd, the sellout shows and time with one another. And in that time, they figured out new things: Tour buses still suck, and it’s too easy to get to missing wives and children. And even if it’s never quite the same, there will always be a place that Jump, Little Children can call home: the Dock Street Theatre, their cathedral at the corner of Church and Queen.

Because at Dock Street, Jump, Little Children were home, safe. They’d only spent a lifetime finding out just where that it is.