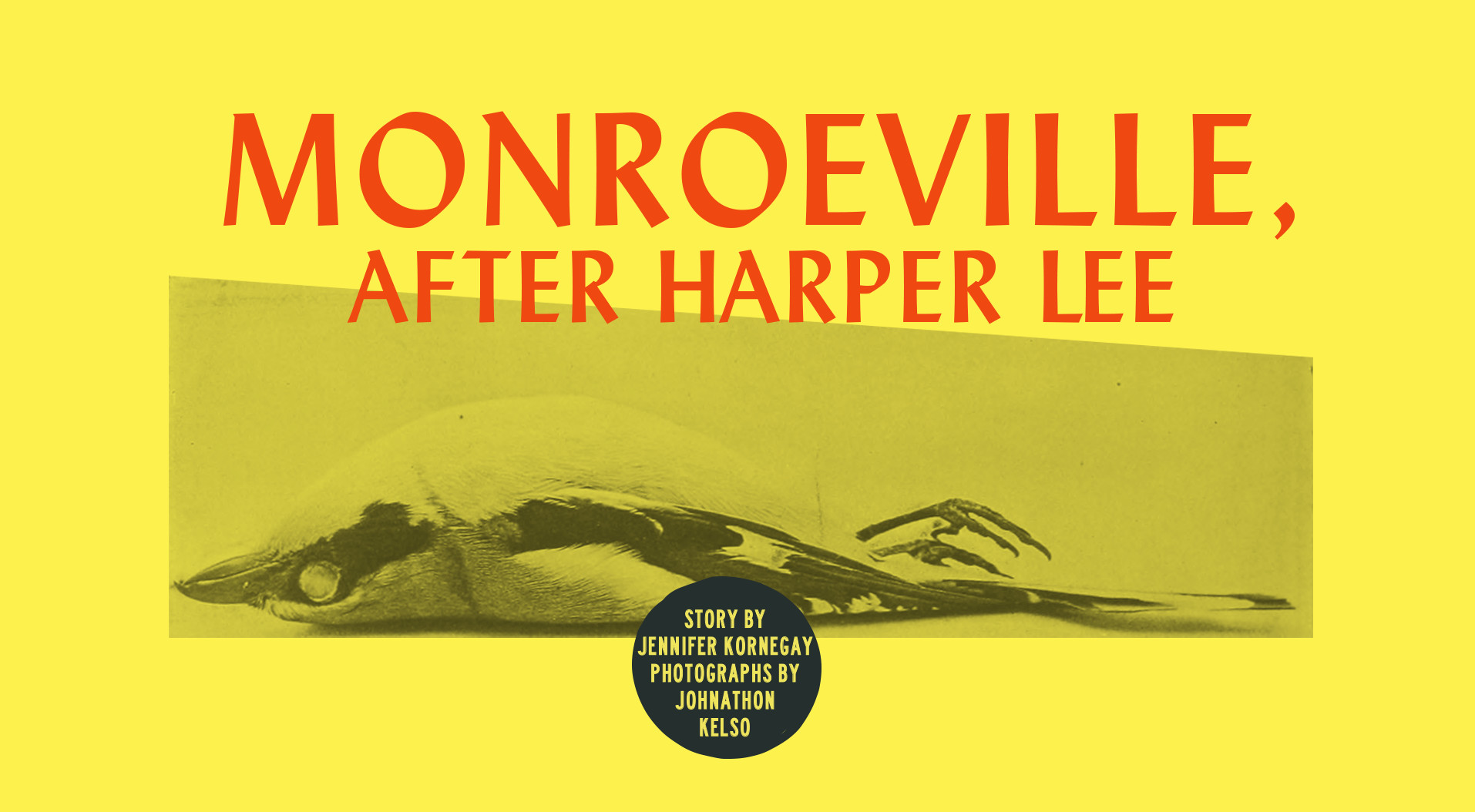

The late Harper Lee spent the final nine years of her life in her tiny hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. Her relationship to the town raised the same question as her writing: How can Southerners reconcile the good that resides in a small town’s people with the bad that can take root in the same spot? Today, Alabama writer Jennifer Kornegay reports on her visits to Monroeville in the months after Lee’s death — and paints a clearer picture than ever of Lee’s archetypally Southern, love/hate relationship with her hometown.

Story by Jennifer Kornegay | Photographs by Johnathon Kelso

On Friday, February 19, 2016, Nelle Harper Lee died in her hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. She was 89 years old. She passed peacefully, and the world mourned.

The author of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” one of the most beloved and influential American novels published in the last century — as well as one of the most scrutinized, “Go Set a Watchman” — had millions of fans, yet only a few close friends. To all but those who knew her best, she was a bit of a mystery, and that, in combination with her talent, made her fascinating.

A week later, on Friday, February 26, 2016, my mother-in-law (and one of my closest friends) died in her hometown of Montgomery, Alabama. She was 68 years old. She passed suddenly, without warning, and her family and many friends mourned. She was simultaneously the toughest and most tenderhearted woman I’ve ever known, and the mystery of how these seemingly opposing traits worked so well together made her remarkable.

My husband and I spent the afternoon of her death at his parents’ house with family, quickly beginning work on funeral arrangements, both as a necessity and as a shield to push back the shock and grief threatening to swallow us whole.

I retreated to the formal living room and sank into the couch. On a marble-topped table in front of me was a stack of glossy, hardback “coffee table” books. Two elaborately painted ceramic dogs next to the stack held a single small book upright between their turned backs, a worn paperback copy of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Between the fancy bookends, beside the pretty books, in the room with crystal candlesticks and stately wingbacks, was this beat-up volume, its frayed, yellowed pages so obviously read many times. Its place there said, “This book matters,” and reminded me of the love of books my mother-in-law and I shared, the long, meandering conversations we had about them, and of the special, almost sacred, place this one book and one author held in both our hearts.

I realized I’d never again talk about anything at all with her, and I cried for the first time that day.

My family is now learning how to navigate a world without my mother-in-law, while Lee’s family and friends do the same. So too, is a place inextricably and forever linked to her, the place of her birth and death, Monroeville. It is pondering what its future will hold without its most famous resident. What will Monroeville without her be like?

To even attempt to answer that question, we must first know the two principal characters in this story — Lee and Monroeville — and their roles in relation to each other. Their tale is underpinned by a common theme in the South: Small-town girl widens her gaze and outgrows her roots. But as it unfolded under a microscope of international interest, it became tangled with misunderstandings and disappointments. And despite Lee’s recent exit from the stage, it’s still being written.

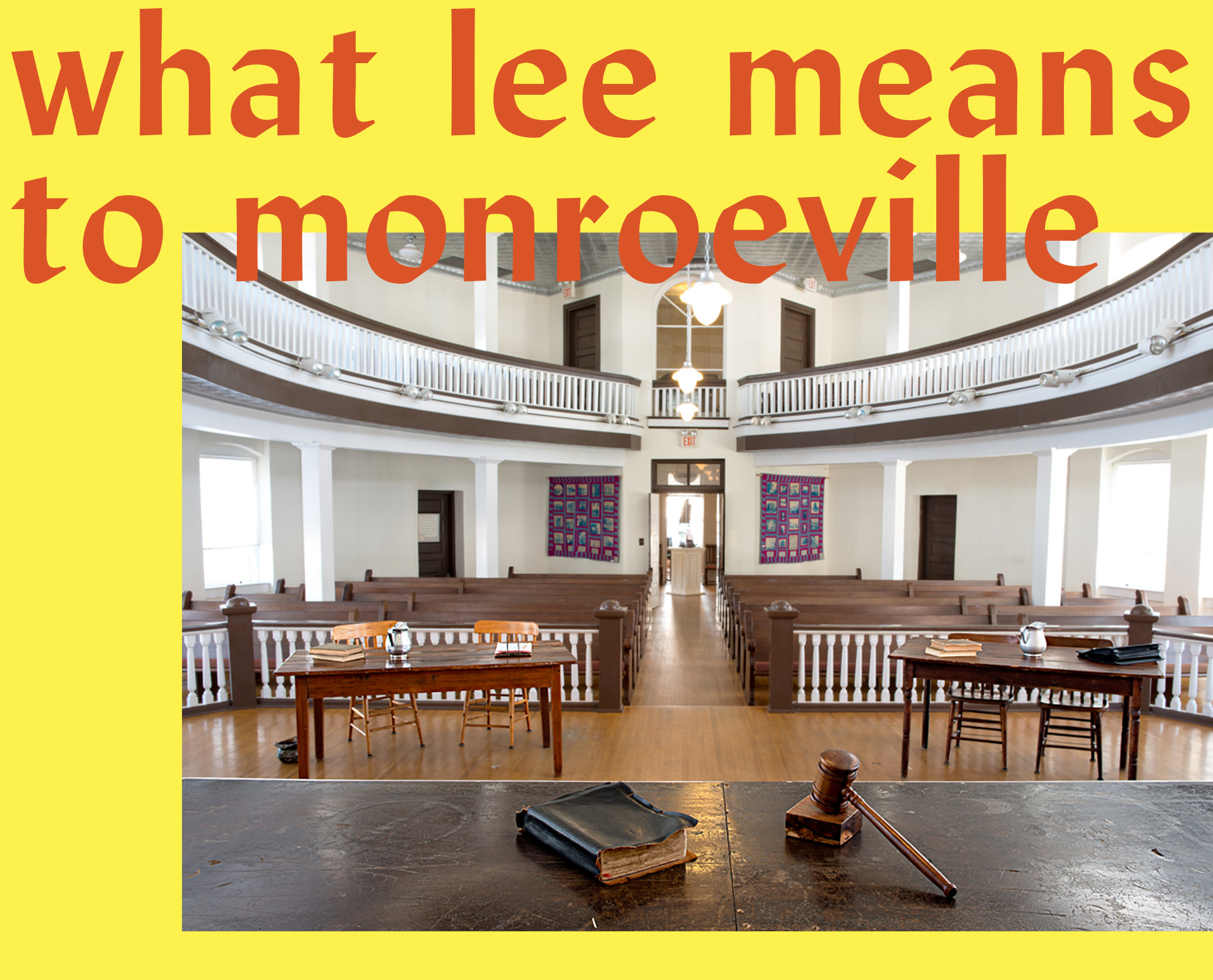

Monroeville was incorporated in 1899 and is the county seat of Monroe County. Both were named for U.S. President James Monroe. Drive into its center today, and there, like a proper lady wearing a frilly white hat, sits the old county courthouse, topped with a wedding-cake-like cupola, built in 1903. It now houses the Monroe County Heritage Museum and sits next to a more modern, boxy building that serves as the current courthouse. Both are surrounded by a fairly typical Southern small-town square, its perimeter lined with little shops, offices and restaurants as well as some abandoned, closed-up spaces.

The town has gained fame not just as the birthplace of Harper Lee but also as the template and inspiration for the fictional setting of “Mockingbird,” Maycomb. Yet anytime she was asked, Lee denied that Maycomb was based on Monroeville.

Her dear friend, historian and retired Auburn University professor (who is also a Baptist minister) Dr. Wayne Flynt laughs at her illogical refutation.

“When ‘Mockingbird’ was published, and everyone said it was just Monroeville thinly disguised, she belligerently denied that it had anything to do with Monroeville,” he said. “Which, of course, is patently absurd. There are so many trails back to Monroeville, both in her psyche and her place names and even specific incidents. There’s no doubt Monroeville is the setting for both of her books.”

Flynt believes Lee would never admit it because she wanted Maycomb to be any place, not one single place. But Monroeville is a place. It’s a dot on Alabama’s map that’s almost 100 miles removed in any direction from any major city and 20 miles off the nearest Interstate. As lifelong resident George Thomas Jones put it, “There couldn’t have been a more isolated country town than here in the 1920s and ’30s.” The 93-year-old museum volunteer and columnist for the weekly Monroe Journal recalled what the town was like during his childhood, which was parallel to Lee’s.

“No mainline highway and no mainline railroad came through here. When I came here in 1926 [at age 3], there were no paved roads or even a sewage system,” he said.

Much progress and many changes have come since then (including the addition of a sewage system), but according to Flynt, the town’s remoteness is one reason among several that it has always struggled with its identity.

“It gets lumped into the Black Belt region, but it really has no antebellum history,” he said. The county’s population peaked in 1900. “It’s been downhill ever since. And it’s the same for the city. It peaked in 1990 and is now 25 years into decline,” he said. Today’s population is approximately 6,300 residents

Agriculture on a small scale dominated the city’s economy until the textile industry moved in, via a Vanity Fair plant, in 1937. While there is still a distribution center and factory outlet, in 1996, the company closed a plant in Monroeville, costing hundreds of jobs; between 1996 and 2007, it continued to downsize, taking more jobs. It was a major blow. “The city has always been pretty one-dimensional,” Flynt said. “If not for it being the county seat, I’m not sure there would be a Monroeville.” And then came Harper Lee.

Nelle Harper Lee was born in 1926 to A.C. and Frances Lee. She had three siblings, Louise, Ed and Alice. By all accounts, her childhood was idyllic. Her mother’s mental illness didn’t overshadow the love and care she received from a father she revered and a much older sister, Alice, whom she adored. There was no book yet. There were no great expectations. There was no legion of clamoring fans. She was not yet Harper; she was only Nelle.

Harper Lee, the writer, was standoffish, an inspiration, a legend. Nelle – the name used by her family and inner circle of friends – was someone else: witty, generous (usually anonymously), a reluctant celebrity. Nancy Grisham Anderson, a former Auburn University Montgomery English professor and now Distinguished Outreach Fellow, is among the foremost Harper Lee scholars in the world, but she was also Nelle’s friend. She stressed the care she took to separate the two Lees. Her academic study of Harper’s works and her conversations with her friend Nelle very rarely intertwined.

“I don’t think we ever exchanged a single word about ‘Mockingbird,’” Anderson said. “But that’s why our friendship worked; she was always wary of being sought after and ‘used’ for the book. I never presumed on our friendship.”

Nancy grisham anderson

But even before “the book,” Lee stood out among her peers. Jones knew her as a tomboy. At some point she took off the overalls and put on a skirt and blouse, but she never stopped being different from other girls of the time. She graduated from Monroe County High School and went to Huntingdon College in Montgomery, where she never really fit in. “We’d hear stories about her in the dorm, wearing men’s PJs with a cigarette between her lips,” Jones said. “It just wasn’t the place for her.”

She left Huntingdon after a year and transferred to the University of Alabama. She began law school there, but quit one semester shy of a degree. In 1949, she moved to New York City, where she wrote “To Kill a Mockingbird.” When she went to New York, Jones, like most in town, lost touch. “We heard rumors that she was writing a book and that it was about the town, about us, but most of us thought, ‘What on earth here could be interesting enough to bother writing about?’”

Jones was A.C. Lee’s golf caddy for a time and remembered that when the book was about to come out, even A.C. was unsure anyone would care to read a story about a little Alabama town. “He visited the local bookstore ’cause he heard that the owner had pre-ordered 50 copies of ‘Mockingbird,’ and this was a man who’d never ordered more than two copies of any book save the Bible,” Jones said. As he tells it, A.C. told the owner he appreciated his faith in his daughter, but he’d buy the extra books if they didn’t sell. “Of course, he didn’t buy a one. They sold out faster than you could blink,” Jones said.

The day “To Kill a Mockingbird” was published in 1960, Harper became an instant celebrity. That same day, Nelle’s life was forever changed. The spotlight on her book and her life was exciting, but equally blinding and unsettling. Lee began to suspect that most of the new faces who now longed to be near her were interested solely in her book. The anonymity New York provided became even more valuable to her, and it’s one of the main reasons she stayed there, until she no longer could.

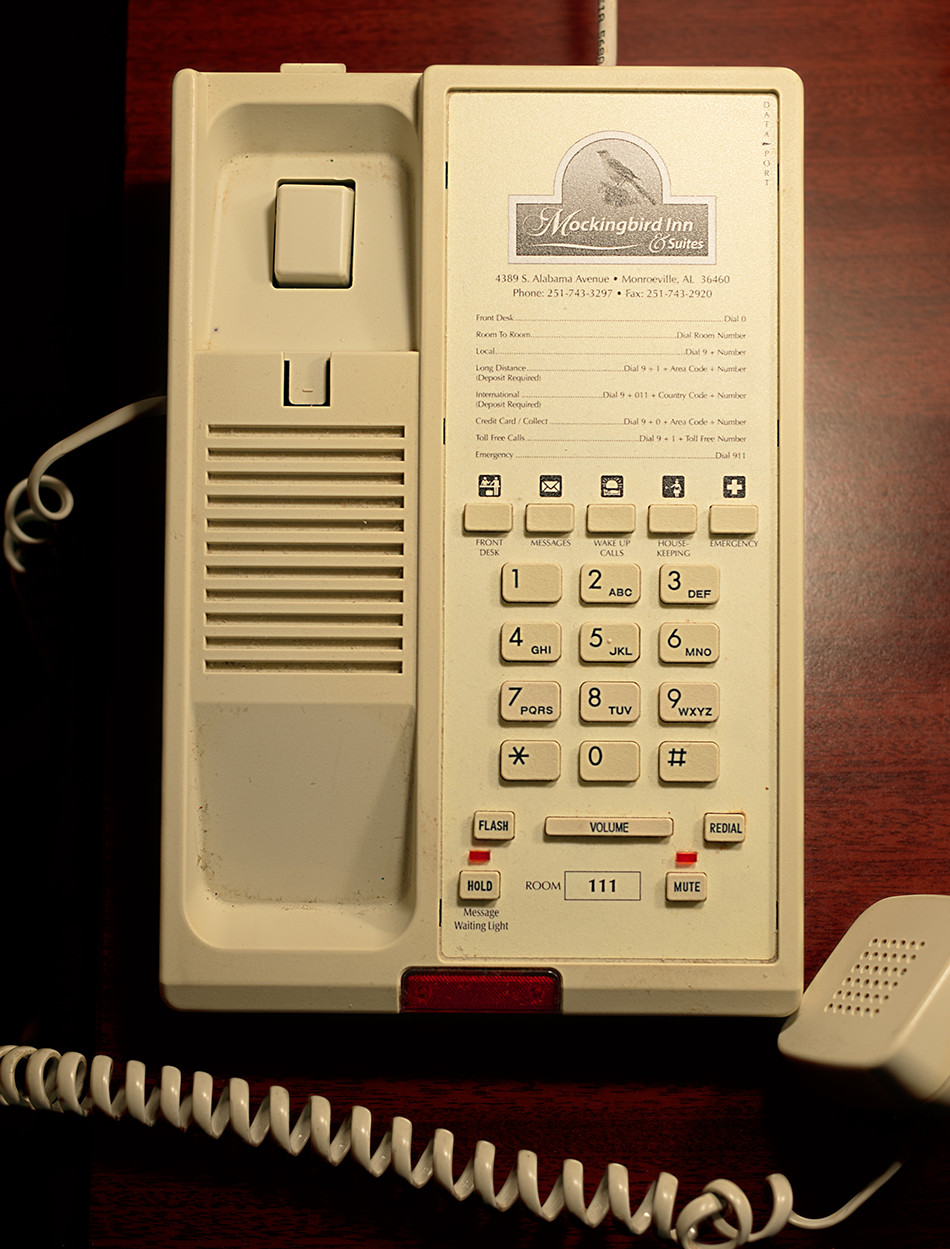

During the initial days of her recovery after suffering a debilitating stroke in her New York City apartment in 2007, she found herself yearning for the softer edges and considerate touches found in the manners that were commonplace in the South. She decided to do her rehab in Birmingham. She thought she’d fully recover and then go back home to New York, but it soon became obvious that wasn’t going to happen. She never regained enough mobility to be able to get around in the city. She’d never live there again.

In Birmingham, she was instantly and easily recognized.

“She couldn’t go out to dinner there without someone wanting a cocktail napkin autographed,” Anderson said. And Birmingham didn’t offer family or a circle of trusted friends either, so when her time at rehab was done (and she’d accepted that a return to New York was out), she decided she wanted to be closer to her sister Alice and the few friends she still had in Monroeville. She moved into a nursing home called The Meadows. It would be her home until her death.

“This was one way in which Monroeville represented frustration to her,” Anderson said. “She was used to being able to stroll the New York streets unnoticed and go to the theater or a baseball game – she loved baseball – without being known or bothered. In Monroeville, there was really nowhere to walk, and by the time she was forced to live there, she couldn’t walk.”

Despite her reclusive reputation, her close friends and those in Monroeville, even those who called her Harper instead of Nelle, knew better.

“She most certainly was not a recluse,” Pat Nettles, a Monroeville resident and a volunteer at the courthouse museum, said. “She was private, and she did not suffer fools. She was never rude, but she could be curt, and I don’t blame her for that at all.” Anderson prefers to call her friend “discriminating” when referring to her desire to be left alone.

According to Flynt, Nelle simply tired of being Harper Lee all the time, and while many in Monroeville acknowledged and deferred to her wish for privacy, those who did not made things difficult.

“When my wife and I would visit and take her out to eat in Monroeville, there were always interruptions; everyone wanted to see her. There was always somebody coming up and saying, ‘Oh, Ms. Lee, my mother was with you at Monroe County High School’ or some such thing,” he said. (Even these trespassers seemed aware that they dare not mention the book.) “Of course, since Nelle couldn’t hear very well by the time she’d had to move to Monroeville, that was always an embarrassment to her; she couldn’t figure out who they were talking about.” She finally decided she no longer wanted to go out much. “But she was not shy, not an introvert. She was private; that is the right word,” Flynt said.

It’s not a word our current culture appreciates or even fully grasps, which is why Lee was sometimes misread and misrepresented, especially by national and international media and especially in the last few years of her life.

“Exposing is such a part of our culture today,” Flynt said. “Something that some of the media never got was that in a world of celebrity where marketing is all about exposing yourself, the idea that there could be someone who not only would not play the role of celebrity but actually despised the role of celebrity was so foreign that they assumed something was wrong with her. She must be senile. She must be being taken advantage of.”

Flynt believes this inability to understand Lee’s private nature was the foundation for the conspiracy theories surrounding “Go Set a Watchman.” Within days of the announcement it would be published, rumors swirled that Lee had never intended for the book to see the light of day, that its publication was a ploy of her greedy lawyer, that Lee’s big sister Alice never would have allowed it if she was still alive. And those rumors were being published in news outlets around the world. An anonymous tip charging “elder abuse,” most likely from someone in Monroeville, even triggered a state investigation.

According to Flynt and Anderson, there was no truth behind the gossip or the investigation, which, once it was concluded, found nothing amiss. Many in Monroeville who voiced concern for Lee’s plight probably came by their opinions innocently. She had become profoundly deaf and almost completely blind, and for those who interacted with her but didn’t know how to communicate with her – “Near the end, I basically had to stand right next to her right ear and yell,” Flynt said – her condition could have looked like senility. Anderson thinks there were more intentional forces at work too.

“I think a couple of folks talking about it just wanted to talk; they wanted their names in the news,” she said.

Aside from a few seeking their 15 minutes of fame, it’s clear that Monroeville, as a collective, adores its most famous resident. A paper sign, Scotch-taped to the window of an insurance office on the square a few months after her death, proclaimed “Monroeville ‘hearts’ Harper Lee.” The local chamber logo features a stylized mockingbird, further proof of her – and her work’s – position of prominence in the town.

How individual folks in Monroeville feel about Lee seems to depend on how they knew her or if they only knew of her. “I think the people in Monroeville had different feelings for her based on whether she was merely a fixture to them or a person,” said Anderson.

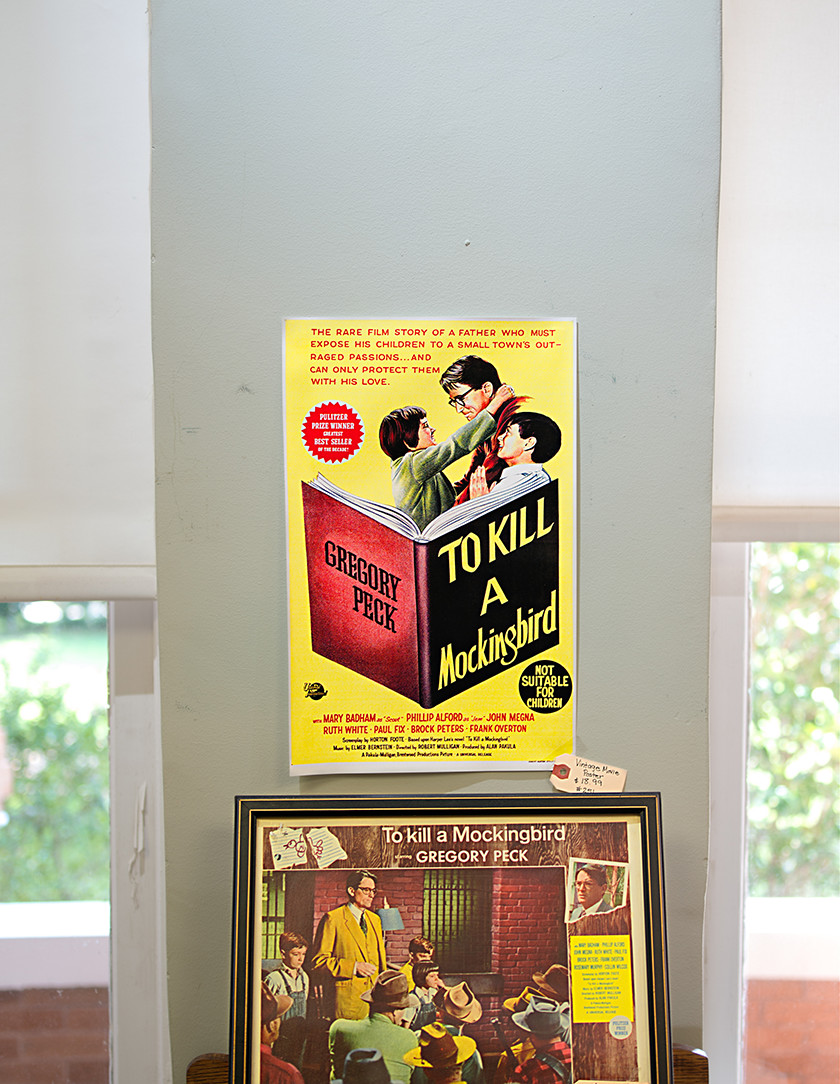

While “Mockingbird” almost instantly made Monroeville a household name, it was decades after its publication that people began to look to Lee’s and the book’s popularity as a way to boost the town’s prospects.

“The idea to make it the hub of a cultural tourism draw really came about after Vanity Fair closed down,” Flynt said. “As a town, you have to find out what will make people come and market yourself that way, and in Monroeville there is this amazing collection of writers, and the town’s pride in its writers is not misplaced or inappropriate.”

It all started with John Johnson, the past president of Alabama Southern Community College, located in Monroeville. “He had this vision of concentrating the area’s appeal, focusing it on ‘Mockingbird,’ the Alabama Writers’ Hall of Fame and the annual Alabama Writers’ Symposium held in Monroeville,” Flynt said. Monroeville’s annual production of the stage version of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and the courthouse museum sit at the center of this vision, and both have a major economic impact on the area.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a group of Monroeville residents (including Pat Nettles) raised the millions needed to save the historic courthouse and transform it into a museum. Once the museum was established, it quickly became clear that a regular source of income was needed to keep the doors open, and the idea to put on the play popped up. In 1991, the museum premiered its production, using a cast of its citizens (called The Mockingbird Players) and the old courthouse grounds and its courtroom for setting and stage. It was a runaway hit, and has grown in attendance every year, usually selling out all of its 12 or so of the annual performances performances held on weekends in the spring, drawing more than 5,000 visitors (and their money) to Monroeville. The names and locations written in the museum’s guest book reveal travelers from spots as far-flung as California, Colorado, Australia, England, Denmark and everywhere in between.

Crissy Nettles, who married Pat’s son and has lived in Monroeville for the last 11 years, has become an integral part of the play, which has become an integral piece of the town’s financial puzzle. She plays Ms. Maudie, and her son performs the role of Dill. To her, the play is a valuable teaching tool.

Crissy Nettles as Miss Maudie Atkinson

Andrew Nettles as Dill Harris

“I think in any small town, where it feels like everyone knows everyone, it's hard to reconcile the hospitality of your neighbors with actions or politics that are unfair or unkind,” she said. “The play has opened up a lot of conversations for us as a family: How and when do you get the courage to speak up for your own beliefs when you know you're going to be ostracized?”

She believes it opens the same doors for the thousands of visitors who come to see it, and that the importance of producing the play in Monroeville is far greater than the money it brings in.

“Maycomb isn't real, but the inspiration for it lives and breathes in the fabric of Monroeville in a way it just can't exist anywhere else,” she said. “When you sit in that courtroom a few feet from Atticus Finch and Tom Robinson and let yourself get lost in their story, it is so easy to hope that just this once the story will turn out differently.”

It never does. But the hope the play sparks is hard to extinguish, and it’s fitting, as hope is one of the book’s lasting themes. “The community makes Herculean efforts to produce, largely with volunteers, the play, which they do so well, and to host the writers’ symposium, and I am proud of the town and the people for those efforts,” Flynt said.

Hope is the engine that drives those efforts — the hope of a bright future — and Monroeville has pinned that hope on Harper Lee. Pat Nettles pointed to aspects of Monroeville’s heritage apart from Lee that deserve preservation and exploration. “We have such a tremendous history with the Old Federal Road, the river, the other communities in the county, so there’s more to us than Harper Lee,” she said.

But it all hinges on Lee; she’s definitely the main draw, bringing an estimated 30,000 visitors (including the playgoers) a year to Monroeville. As Flynt noted, the town and area have produced other accomplished writers (Mark Childress and Cynthia Tucker to name a few), but Lee is why the town was designated The Literary Capital of Alabama. The writers’ symposium gives out an annual Harper Lee award. The museum contains genealogy records for the county and artifacts relating to area history, but exhibits on Lee (and Truman Capote, too) are dominant. The playgoers from around the country and the globe don’t come to Monroeville to see the show for its acting and stagecraft (although both are wonderfully done); they come because they want to witness the story unfold in its natural habitat.

The Monroeville/Monroe County Chamber of Commerce declared 2016 “The Year of Harper Lee.”

“We did it because the past year had been so phenomenal in terms of visitors and that was due to ‘Watchman,’” said the chamber’s executive director, Sandy Smith. On what would have been Lee’s 90th birthday this year, April 28, the town unveiled a marker dedicating to Lee a sculpture on the old courthouse grounds of three children reading a book.

“She did a lot for this town, starting with putting us on the map,” she said. “I think she got impatient with the town from time to time, but her works were gifts to the town. We’ll always be thankful.”

It’s no surprise considering her job title, but Smith also pointed to the economic impact Lee and her works have had, one that has steadily gotten bigger through the years. “It is enormous. The people come for the play or just to see the courthouse and museum and spend money here on gas, shopping and food,” she said. “It really escalated when she moved here permanently. Her presence really drew people here. Everyone wanted to see her, and they looked for her.”

But they couldn’t find her. Smith, like many residents, went out of her way to guard Lee’s privacy. “We were all so proud of her; the whole town tried to protect her. We never told anyone where she was. When we saw her, we’d speak, and she was always pleasant, but we did not ask her about the book.”

Pat Nettles wonders if Lee was aware of their attempts to buffer any intrusion. “Visitors to the museum always asked about her, where she was, but we never told,” she said. “We all, the entire town, helped her maintain that privacy as best we could. I think she knew that; I hope she did.”

Did Lee return her hometown’s sentiments? The only person who could say for sure is no longer with us (and probably wouldn’t say, even if she was). But when close friends speak of Monroeville and Lee, one word gets repeated: frustration.

Perhaps no one still living knew her better than Flynt, who, per her request, delivered the eulogy at her funeral. He offered his thoughts on her feelings.

“There were obvious patterns she observed in her hometown that she could never reconcile to the values that people said they held,” he said. “That continually frustrated her.”

That same frustration burns through the words of her second novel, “Go Set a Watchman.”

“In that book, her uncle Jack and father claimed something that they didn’t practice,” Flynt said.

Yet in “Mockingbird,” Lee paints a hopeful portrait of a town, one with problematic viewpoints and values to be sure, but also one with pinpricks of right and good piercing the darkness. “There was a part of her that found something special about her hometown, and I think she captured that in the childhood memories we read in ‘Mockingbird,’” Anderson said.

But like the grown-up Scout, Lee saw another Monroeville too, through a different lens, one honed to an objective focal point by distance and time away. “The town was frustrating to her,” Anderson said. She was frustrated by prejudices that were by no means unique to Monroeville (or even Alabama), but there. “We see this in the view of an adult Jean in ‘Watchman,’ when she had left and was viewing it as an outsider,” Anderson said. “Like her main character, she was frustrated with that world. Still, both of the pictures of small-town life in both books are very realistic. To me, the ‘Watchman’ view doesn’t contradict the ‘Mockingbird’ view; they are both true.”

Flynt points to her departure, her visits home and the circumstances surrounding her eventual return as further evidence of her struggle to relate to a place where she never felt like she belonged, a struggle that grew fiercer as she got older.

Dr. Wayne Flynt

“I think the most important evidence of anything is not what people tell you, but what they do,” he said. “And what she did, despite the fact that her mother and father were aging very quickly, and even though her father did not want her to, was move to New York City.”

Although many accounts say she split her time between Monroeville and New York, they’re not accurate on that point, according to Flynt. “Until her stroke, she never lived in Monroeville again,” he said.

She did visit family regularly. She went home each year around Thanksgiving and would usually stay until right around the first of January. “Sometimes, she’d get bored, and leave right after Christmas,” Flynt said. “I think her happiest moments on any visit to Alabama were when she was catching the train back to New York.”

Crissy Nettles has no trouble believing that.

“Obviously, she loved her family and friends here, but she was incredibly well-read and cultured and curious,” she said. “I imagine it would have been difficult to feel inspired and intellectually challenged day after day in the relative isolation of Monroeville after she had created a life for herself in New York.”

Anderson echoed Flynt on this point, but like Crissy, stressed that it probably had as much to do with the positives offered by big-city life as it did the negatives associated with life in a small-town fishbowl. When Lee did finally move back to Monroeville, the reason for her return surely colored her perception of the homecoming.

“She had to come home; she didn’t choose to at that time,” Anderson said.

Relationships are fickle, complex things that constantly evolve. Such was the case with Lee and her hometown. Despite Monroeville residents’ obvious affection and the sincere efforts of many to respect and secure her privacy, the suspicion that people were only interested in “Mockingbird” and how they could benefit from it bled into her relations with Monroeville.

City and museum officials are adamant that everything they have done was to honor and applaud Lee. Ask other Monroeville residents, and most will tell you the same. And there’s no reason not to believe them. But Monroeville has come to rely on the fame and appeal of both Lee and her works, a burden she definitely felt weighing on her, though she had no wish to bear it.

“Monroeville wanted her to be someone they could trot out to wow visiting dignitaries and economic-development teams,” Flynt said. “But she never felt any need to be the town spokesperson or felt that it was her responsibility.”

She never once saw the play. “I don’t think that was because it bothered her, but because she knew she’d be covered up in people if she was there,” Flynt said. He invited her to go with him once, an invitation she flatly declined. “She said, ‘I will never see the play. When that thing is held and during the writers’ symposium, you’re not going to find me in Alabama. I always leave town.’” She often escaped to California to visit Gregory Peck (who played Atticus in the film version of “Mockingbird”) and his wife.

Jones’ personal feelings about Lee and their shared home are mixed. “The book did so much for this town, but I think she could have done more for Monroeville than she did. She didn’t owe us anything; she wasn’t obligated to do more, I know that, but I just wish she had wanted to. When she sued us, that cost us. She didn’t have to do that.”

His statements put a small crack in the veneer that the town has painted over the tension that had tightened between it, and specifically the museum, and Lee in the last few years of her life. In 2013, Lee sued the museum for trademark infringement. The museum’s gift shop had been using the “Mockingbird” title on some souvenir items, such as T-shirts, which it was selling to tourists, and after years of this, Lee could no longer look the other way. The two parties settled, but the terms forced the museum to stop selling certain items. That was by far the most benign effect the case had. Fueled by the depth of affection they had for Lee, museum staff and Monroeville residents were shocked, and some were angered, by Lee’s actions. There were whispers that the suit was the work of her lawyer, not Lee. It was an uproar Lee herself never comprehended. Flynt explained why.

“She was just protecting the trademark in the same way that anyone with a trademark protects it,” he said. “You have to protect it to keep it strong. To some degree, I understand why it upset the museum, but I don’t think she ever did. She didn’t enjoy doing it. And I understand why they tried to blame it all on her lawyer. Many didn’t want to believe that Nelle made the decision.” They didn’t want to be upset with their beloved Harper.

Then last year, the play that is a crucial revenue source and point of pride in Monroeville found its future uncertain. The publishing company that owns the performing rights would not extend them to the museum past the 2015 season. The announcement had the town and its leaders dismayed and worried. Again, rumors spread and accusations were made. Some claimed that Lee’s lawyer was behind the publishing company’s decision. Within days though, Lee formed a nonprofit called Mockingbird Company, and it was granted the rights to put on the play. It meant the show would go on, and go on in Monroeville, keeping the cast of locals intact, many of whom had donned their costumes and inhabited “Mockingbird’s” characters since the first performance a quarter-century ago. This past spring, the play delighted audiences once again, and Lee’s scenes played out on the museum grounds and in the historic courtroom.

But going forward, the museum will miss out on needed funds under the new arrangement, a cut that reopened the old wound of the lawsuit. “There has been some immense tension, and that saddens me. Nobody benefits from that,” Anderson said. “I love that museum and hope it isn’t damaged because of it.”

Still, many directly involved (and affected) don’t seem to harbor the resentment that Jones alluded to or at least won’t put voice to it. “It was a shame, but things are working well this season,” Pat said. “That is what happens in a small community; we pull together.”

Even faced with these issues, it seems the majority of Monroeville residents continue to feel a mix of pride, respect and love for Lee. Or at least who they perceive her to be, according to Flynt.

“They canonized her and never understood her; they loved her without understanding her,” he said.

Monroeville is not alone in loving someone without really knowing them. Millions around the globe “love” Lee and feel close to someone they’ve never seen or spoken to. But she spoke to us. Her written words kindle a kinship, an intimacy that is no less powerful for its falsity.

On the day Lee was laid to rest, friends and family were wary of what an outpouring of that love might look like. On February 20, 2016, only a day after her death, Lee’s funeral was held at the First United Methodist Church in Monroeville, where she was an active member. About 40 people attended the private ceremony, and though the doors to the church were locked to keep out reporters and any other uninvited guests, that precaution proved unnecessary. The respect the town had for her was evident again.

“To the everlasting credit of the people of Monroeville, they could have made it a circus, but they didn’t,” Flynt said. “It’s a great testimony to people that they didn’t cluster around or try to come to the funeral, despite their great affection for her.”

Her grave is in the Lee family plot, near sister Alice and her father. The small hill, a few hundred feet from a bushy, unruly camellia with bright pink blooms, is now visited almost as much as the museum. A rectangular swath of crumbly red dirt juts out in front of the small granite square engraved with her name, waiting for the grass to come back and cover evidence of recent interment. Well-wishers are pinching fuchsia flowers off the camellia and tucking their short stems into the soft earth. They’re digging into their pockets too, leaving pennies, quarters and other change on her marker. No one knows who placed the first coin or what it means, but Anderson has a guess.

“I think it is a way of showing respect, a final tribute to her based on the coins and trinkets left for Scout and Jem by Boo Radley,” she said.

The method of tribute is specific more to Harper, the writer, not Nelle, the woman. This continued devotion to their native saint in the only persona in which most recognized her – the only way she’d let them – is beautifully poetic to Flynt. “One of her favorite books was Norman Maclean’s ‘A River Runs Through It,’ and at the end of that story, one son is talking with his father about the other son’s tragic death. He tells his dad, ‘We can love completely without complete understanding.’ That’s as close to a perfect description of the Monroeville people as I can think of. Maybe that’s the best thing we can say about this small town, its capacity to love you without understanding you.”

Anderson hesitated to comment exactly what Lee felt for Monroeville, but she pointed to some of her friend’s own words for clarity.

“There is an article where she is quoted saying the one thing she really wanted to achieve in her life was to record middle-class Southern life. She said, ‘There is something decent to be said for it and something to lament in its passing,’” Anderson said. “She didn’t mean the plantation life, just wonderful small-town life. She thought it held something universal, and I hear in those words, if not love, certainly respect and an acknowledgement of the significance of that world. It was her world and is the world of both of her books.”

While it seems foolish to assert that there’s no one in Monroeville still nursing hurt feelings over the legal clashes, most have moved forward and are optimistic about the town’s continued part in Harper Lee’s story. In Flynt’s eyes, this attitude makes the town even more endearing.

Mel’s Dairy Dream, A burger and fry shack THAT sits on the property where Harper Lee’s home once stood.

“It’s a great testament to them that their affection, overall, has not wavered,” he said.

And no matter what the town and Lee meant to each other, they are eternally connected. As Jones put it, “You can’t divorce one from the other.” On some level, Lee needed Monroeville, and Monroeville still needs her.

“When Vanity Fair was thriving, we were the manufacturing center, and it was very important to us. It was a tremendous blow to lose that,” Pat Nettles said. “Around the same time, we had a pulp mill running. That was a golden time.”

Smith sees golden times still on the horizon. “We have Georgia-Pacific here as well as a pre-cast concrete plant. And everything about Harper Lee and the interest in her work keeps growing,” she said. “Now, with her passing, we are seeing just as many visitors if not more.”

Crissy Nettles thinks things might even get a bit easier in Monroeville. “While she was alive, there was great tension in wanting to honor and celebrate her without exploiting or insulting her,” she said. “Now that she's gone, we still feel the need to be respectful, but I hope the sense of having to walk on eggshells disappears with time. Some entities in Monroeville have been accused of unfairly exploiting Lee. I don't think that was ever anyone's intention, but we are gun-shy now and still wonder how our actions would make her feel.”

She also sees an opportunity for the museum’s collection to expand and allow more people to learn about Lee and her hometown. “I hope Lee's heirs will donate some of her papers and personal effects to be archived in our museum, where they will be treasured and cared for and made available free of charge to literary scholars,” she said.

For literary scholars and average Lee fans alike, one thing worth learning about her is this: Nelle Harper Lee was more than Harper the writer, more than the Pulitzer Prize on a pedestal, more than Nelle, more than the characters she created, more than her childhood memories and her adult disillusionment that stripped them of their gilded edges; she was all of them.

Whatever we do or don’t know, feel or have felt about Lee, it wouldn’t have mattered a whit to her. It never did. If, as Atticus once advised, anyone was able to climb into her skin and walk around a bit, they’d realize that she was quite comfortable there; she didn’t crave or need the world’s attention, understanding, approval or love.

“She was always secure enough that she didn’t care what we thought of her,” Flynt said. She alone was enough.

One of my last conversations with my mother-in-law included a discussion of Lee. We were talking through the drama that had surrounded the publication of “Watchman” and the rights to the “Mockingbird” play changing hands.

“How strange must it be for her?” my mother-in-law mused. “Everyone thinks they know her; it’s like we’ve claimed her and feel some right to an accounting of everything she thinks or does. Some of the talk about her sounds like she’s an entity, not a person. But she’s really just a girl from Alabama.” Nelle was just a girl from Alabama. Harper Lee became an icon.

And while Nelle is gone, Harper Lee will live on. She’s cemented her place in the cultural consciousness of the world, in the literary legacy of Alabama and in the history of one tiny country town. And because of that, Monroeville — what it was, what it is and what she imagined and hoped that it could be — will live on, too.