Neighbors of the Fence

The stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana from north Baton Rouge to New Orleans has been plagued with so many industrial accidents and chemical spills that it’s developed an unfortunate nickname: Cancer Alley. Today, journalist David Hanson takes takes us to the Standard Heights neighborhood of Baton Rouge, where the residents and a small army of advocates explain what it’s like to live with house-rattling refinery explosions, salt domes collapsing in barge-eating sinkholes and mysterious flakes falling from the sky.

In the time it takes for me to pull out an old film camera and set the focus, there’s already a car coming down the empty street toward us. I’m standing in the back of a pickup truck shooting a thin, dead-straight road surrounded by empty grass lots and mature oak trees. It used to be a residential neighborhood of small bungalows and fenced-in yards. Today there’s not a brick stoop or foundation left, and the weeds have begun to consume the road’s edges, as happens to anything abandoned in southern Louisiana.

A Baton Rouge police car, then another, then a minivan convene behind the truck. A young plainclothes officer asks what I’m photographing. He’s nice enough. This empty neighborhood of trees, I tell him. An older gentleman from the minivan asks if I’d shot any photos of the Exxon plant across the street. He says this is ExxonMobil property and I can’t take any pictures. Homeland Security. Although it looks like a public street in a forgotten city park, most of the Standard Heights neighborhood of north Baton Rouge has been bought by ExxonMobil, the former residents relocated and the homes razed. Buyouts and relocations have become common solutions in southern Louisiana, where more than 150 petrochemical facilities operate, many of them within a football’s throw from historic neighborhoods.

The 1,800-acre ExxonMobil Standard Heights plant is the largest of the massive refineries that hug the Mississippi River from north Baton Rouge to New Orleans. Some call this span of petrochemical plants “Cancer Alley.” Some call it work, some call it home, and we all call it a major source of fuel for our cars and ingredients for everything from dog food to fleece sweaters. I’ve come to southern Louisiana to see what happens when one-quarter of our nation’s bulk commodity chemical production squeezes into a narrow, populated, riverine path complicated by deep poverty, house-rattling refinery explosions, salt domes collapsing in barge-eating sinkholes, mysterious flakes falling from the sky and a curious lot of homegrown community advocates who have been ardent watchdogs since before Erin Brockovich was a household name.

The Exxon security men run my license and let me go, suggesting I not come back after dark. That’s when the neighborhood gets really dangerous, they tell me.

A mostly abandoned square of the Standard Heights neighborhood tucks into a corner of the Exxon Mobile plant in North Baton Rouge.

Rose Christopher, her husband Willie, a few kids and some grandchildren live in a tidy house on Ontario Street. She’s been there for 45 years. Pimpernel, Cedar, Lobelia, Linwood and Ontario streets used to be full of homes. Now Rose Christopher has only a handful of neighbors. It’s oddly quiet, almost pastoral. I meet Christopher and her family as the sun sets behind the plant’s glowing towers and rusting tanks. A pit bull lifts onto its back legs straining against a rope tied to the garage. Christopher invites me into the kitchen.

“I wasn’t moving,” she says. “My house was bought and paid for. I wasn’t going into debt and starting all over again. Exxon didn’t offer enough to make a note on a new house.”

She pulls out a letter typed on letterhead from a Baton Rouge attorney. They get them occasionally, asking that they contact the law office about injuries associated with their refinery neighbor. As far as they know, I’m another white dude peddling the power to settle things with Exxon. The conversation quickly veers toward the maladies that literally fall from the sky.

“About four years ago I woke up to find a lot of brown stuff outside and all over my car,” says Rose’s husband, Willie. “I called the Exxon number and they sent somebody down with some white suits, all masked up. They went up in the attic and came back down. They said they’d let me know what they found and I never heard from them since.”

“There was the explosion about 10 years ago,” he continues. “It knocked the front door in. Broke sills off the foundation. But I’m 76 years old. Ain’t no way no one’s going to finance me a new home.”

Raekwon Savoy, Rose Christopher’s grandson. Most of Raekwon’s neighbors have moved out of Standard Heights, bought out by ExxonMobile after leaks and explosions. Their subsequent lawsuits compelled Exxon to offer relocation packages to its closest neighbors.

Four of us are sitting in the kitchen, the television on in the dark living room behind the wall. Rose’s daughter, Peggy chimes in, “Growing up here was wonderful. I still live here. But the plants have a nasty smell that comes every other day. It’s like sewage or pig slop. It comes all through the house. So I wouldn’t miss anything by moving away.”

I walk out into the night and down the empty, dark road. I don’t smell anything tonight. The Exxon plant emits a subtle hum and the low clouds reflect its golden glow. In the opposite direction, beneath the broad, muscular arms of a century-old oak tree, the Louisiana State Capitol Building, the nation’s tallest statehouse, makes a towering reflection of the refinery’s golden light. I set up my tripod and shoot from the shadows.

Willie Fontenot’s “Toxic Tour” is not found in State of Louisiana tourism brochures. We’re a few miles north of downtown Baton Rouge on Scenic Highway, the most ironically named road in America. We’ve just passed Standard Heights, where the Christophers and a few other holdouts remain as fence-line residents.

“On our left, you’ll see a lot where industrial chemical trucks were cleaned,” Willie says, pointing out the window. “On our right is a permitted, commercial, hazardous-waste incinerator. We just crossed over Monte Sano Bayou, one of the most toxic hot spots in the country.”

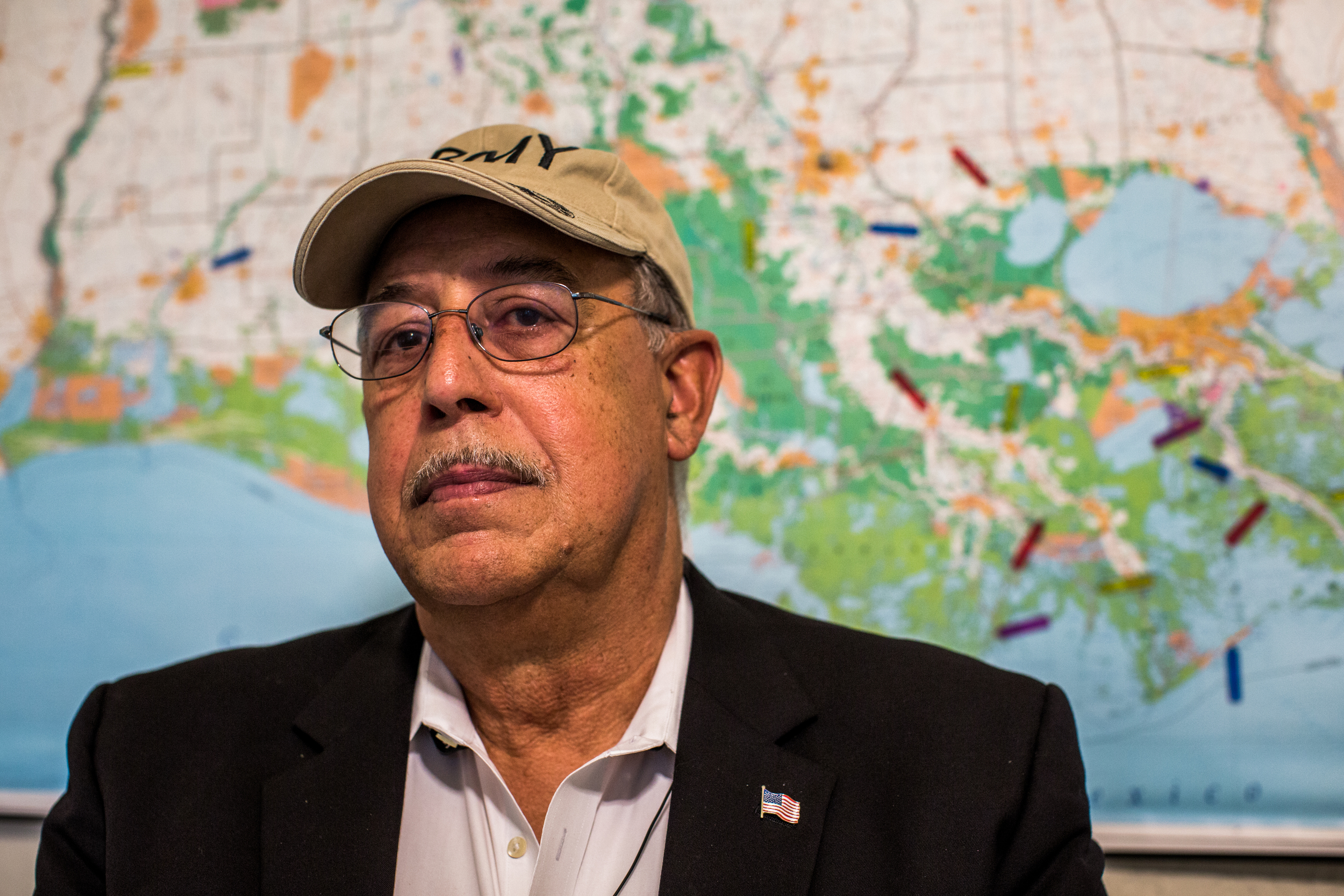

Willie spent 27 years working as a community outreach liaison in the Attorney General’s office, a sort of live conduit between residents and the state government. His 140-mile tour makes a long, thin loop surrounding the Mississippi River from north Baton Rouge to Gonzales, about halfway to New Orleans. Willie rides shotgun. He’s a soft-spoken, unpretentious man in jeans and a flowered button-up shirt. His thin, parted hair still seems boyish despite his thick glasses and a recent string of strokes, the byproducts of being 73 years old. A Louisiana native, he seems at ease with his lifelong role of David in battles with Goliaths.

Willie Fontenot along the west side of River Road.

Willie is legally blind. Some of his close relatives married each other, resulting in a rare condition that affects 20 percent of offspring. “We’re a family of eight kids so statistically we’re right about on track,” Willie says. You’d never suspect it, though. He directs me up Scenic Highway and points out the locations of existing and former chemical facilities and oil refineries as if he’s reading billboards. I’m driving with a map in my lap. West of Scenic Highway, the Devil’s Swamp pokes a dark green finger into a 180-degree bend of the Mississippi River. One bend above that is Profit Island. It’s like riding through the world’s most cynical Monopoly game. Willie tells me to turn onto U.S. Highway 190, and we climb onto the Mississippi River Bridge. The Capitol building sits like an upside-down exclamation point, sunlight revealing the art deco details on former governor Huey Long’s monument to political power.

“When I started working for the Attorney General in 1978,” Willie says, “my office was on the 23rd floor of the Capitol. I didn’t have any windows, but I could easily take the elevator to the 30th-floor Observation Deck. I’d often see large rainbow sheens covering the surface of Capitol Lake. In 1983 Attorney General (William J.) Guste asked me to find the source of that pollution. We found it – train-engine oil from a nearby Kansas City Southern rail yard. The illegal discharge pipe was closed, the KCS officials embarrassed, and the oil slicks stopped. But I wondered then: If the lake in the governor’s backyard is polluted, what hope is there for any other water body in the state?”

Thirty-one states and two Canadian provinces have been contributing their organic detritus to the Mississippi River delta for millions of years. As the river slows into the Gulf of Mexico, it can’t hold its suspended baggage. Sand and mud fall out first, creating sandstone and clay layers. More lightweight organic materials continue a little further before laying to rest in a rich bed of ooze. Left exposed for long periods, the ooze would decompose, but because the river is constantly shifting course, an era of sand deposition periodically covers the organic compost, insulating it from deterioration. Over time, as more sediment and ooze get deposited and insulated, the weight of it all compresses and cooks the compost into oil (or natural gas, depending on the temperature range).

The highly viscous oil wants to move upward toward less pressure. It percolates between weak sandstone layers until it hits an impermeable shale or mudrock shelf, where it pools. The trick is finding the pools, and the Gulf of Mexico has provided the Mississippi River delta with what amounts to a geologic divining rod: salt domes.

During the Jurassic Age, the Gulf of Mexico went through a period of restricted circulation, laying down salt deposits in shallow bays as if they were homemade Popsicle molds. The salt layers were then buried under more river sediments. Like the oil, the low-density salt globs drifted toward the surface, attracting nearby oil pools with their upward pull. For a while, it all just sat there: old Gulf salt, dinosaur bones and Rocky Mountain quartz crystals, all frozen in geologic time.

Then, in 1901, Anthony Lucas, a Croatian-born geologist known mostly for finding salt deposits, tapped into oil at Spindletop in Beaumont, Texas. The term “gusher” was born, along with the modern-day oil rush. This was the Wild West of resource extraction, complete with open-air oil pools and liquid waste running freely down stream beds. A Shreveport well spewed natural gas and occasional explosions for years, prompting Louisiana’s first conservation regulation in 1906, a law prohibiting oil and gas companies from allowing wells to burn.

By the time Huey Long became governor in 1928, oil ruled Louisiana. The bellicose Long wielded his populist, share-the-wealth club at the oil and gas giants. His move in 1929 to levy a five-cent tax on every barrel of Louisiana oil led to all-out fisticuffs in the state legislature. Long managed to fund many of his ambitious social welfare programs with oil revenue. There was just one catch, a tacit agreement that the state wouldn’t bite the hand that fed it with bothersome meddling in industry affairs. The industry, like any of us, tends to remember best the things that benefit it most.

“From Baton Rouge to New Orleans, the great sugar plantations border both sides of the river all the way, . . . Plenty of dwellings . . . standing so close together, for long distances, that the broad river lying between two rows, becomes a sort of spacious street. A most home-like and happy-looking region.”

- Mark Twain

After crossing the Mississippi above Baton Rouge, Willie and I beeline it down the west bank of the Mississippi, past the welcome smell of coffee brewing from Community Coffee’s giant roasters in Port Allen. River Road parallels both sides of the river, a clumsy, zigzag outlining the Mighty Miss. A few strip malls and long, thin subdivisions make patches in the bushy sugarcane fields. In Twain’s time, River Road was prototypical Plantation South. Skinny wedges of land radiated from the river’s edge, sugarcane and oak trees for miles, broken by tall, white-columned plantation homes, the low-slung, weathered slave cabins hauntingly absent from the gauzy perspective of contemporary travelers such as Twain.

Willie points out the Dow Chemical Co. plant ahead of us. It gradually rises from the sugarcane like the first glimpse of a space station in a sci-fi film. In the 1980s its 1,800-acre plant encroached to the doorstep of Morrisonville, a community of roughly 110 homes settled by freed slaves. Dow eventually bought out most residents, fearing more costly damages if there were an explosion or toxic leak.

“Dow never saw these neighbors,” Willie says. “The residents were invisible until the company decided to remove them from the neighborhood for fear of lawsuits.”

We continue south through historic Plaquemine – one-way Church and Eden Streets running in opposing directions – and back into sugarcane, subdivisions and a couple of new vinyl-chloride plants, Axiall and Shintech.

“In 1980 Georgia Gulf was named Georgia Pacific Chemical,” Willie says. “There was a lot of rainfall that year and they decided to pump their full waste pits directly into the Mississippi. Investigators later determined that more than 42 tons of phenolic waste were in the pits, a breach that would have gone unnoticed except that when the phenols combined with the chlorine used to kill bacteria in the New Orleans drinking water system, it created chlorophenols, which have the strong taste of oil. It wasn’t enough to be a health threat but it was enough pollution to make all the water, red beans and rice and Dixie Beer in New Orleans taste like motor oil.”

Willie speaks with a tone that’s both soft-spoken and earnest, folksy and academic. He’s clearly curated his tour, and the retelling of egregious spills and strong-arming tactics over so many decades, often to the same people, begins to sound like magic realism or folklore.

“I’m not sure what got me interested in pollution,” Willie says. “As a kid, our father would take us down to New Orleans and when we’d cross the U.S. 190 bridge, we’d gag on the smells coming from the plants. I really preferred when we crossed on the ferryboat because you couldn’t smell it as much.

“My job with the attorney general’s office was to go out and help people figure out what was the problem and how to deal with it,” he continues. “Usually, these folks didn’t know their next-door neighbors or their parish council member or city official. Did they know anyone at the newspaper? At City Hall? Did they know how to find property ownership records in the court office? I helped them make the right friends. Today they call it ‘environmental justice.’”

A rare Mississippi River bluff on the campus of Southern University.

Our Toxic Tour takes the bridge, looping across the river south of Donaldsonville and regaining the east-side version of River Road in Burnside. We pass the turn for The Cabin, Theresa and Al Robert’s roadside family restaurant and the epicenter for a legendary Louisiana environmental battle. The Save Ourselves (SOS) campaign pitted California hazardous waste giant I.T. Corp. against a fierce group of Burnside residents led by Theresa and Al Robert, nurse Ruby Cointwell, Willie and attorney Steve Irving.

“I’d never even heard the term ‘environmentalist,’” Theresa tells me later, over the phone. “We were industrial people. Our families worked for oil and gas. We just assumed they took care of their stuff. But when they started talking about putting the world’s largest hazardous-waste facility behind us, we started asking questions.”

That is not hyperbole. In 1979 Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards proudly proclaimed the plan for California-based I.T. Corporation to build the “largest hazardous-waste plant in the world.” It was meant to be a positive thing, and in hindsight reveals the industry’s profound confidence in statewide political and regulatory compliance. About the only wheel that hadn’t been greased was the residents living next to the proposed plant.

“Ruby had been seeing higher instances of childhood cancer in the clinic in Ascension,” Theresa says. “We wanted to know more about this I.T. company from California. We started talking to neighbors. The young man’s death in Bayou Sorrel was still fresh.”

In summer of 1978, 19-year-old Kirtley Jackson died instantly when he opened the cock valve on his tanker truck, its hazardous sulfur waste forming a lethal hydrogen sulfide cocktail with the toxic-waste pit. It was a tragic wake-up call to the industry’s closest neighbors. Suddenly the plants and the products they stored in rusting tanks or pits or hauled around in trucks and trains weren’t so benign. News from up north dovetailed with the developing narrative as citizens and activists made the very public Love Canal stand against criminal pollution involving a toxic waste site and a school. Theresa, Ruby and an increasing number of their neighbors developed deep distrust of industry and the government that was supposed to ensure safety.

“Willie helped us understand the system and how we looked up records,” Theresa says. “I was pregnant with my third, and Ruby and I would carry a portable copy machine into the DNR office to make copies of the records since they wanted to charge us a quarter per page to do it on their machine. We were just regular old housewives, not technical researchers.”

They formed an organization called Save Ourselves (SOS) and, with Willie’s help, connected with Steve Irving, a Baton-Rouge-based attorney with a growing resume of representing fence-line communities.

“With SOS and I.T.,” says Irving, “the longer the process was delayed, by doing nothing other than making them follow the rules, the more we effected the economics of the project. There isn’t as much of a goldmine for the big companies if they have to follow the same regulatory rules as everyone else.”

After 10 years and countless close calls that nearly allowed I.T. to carry through on the project, the SOS case finally made it to the Louisiana Supreme Court where Irving and SOS won their suit against the State of Louisiana Environmental Control Commission.

“The case is chronicled by Professor Oliver Houck in the Tulane Law Review,” says Irving. “It is unprecedented for a law review chapter to be written on one case like that.”

The ruling marked a watershed moment for how decisions would be made for future permitting of plants. It put the health and welfare of citizens first and foremost, requiring a five-step inquiry during permitting: the avoidance of impacts, a balancing analysis, and consideration of alternative projects, sites and mitigating conditions.

But more importantly, the SOS decision gave residents living near proposed industry sites a seat at the table. And the tedious battle sowed the seeds for a generation of uniquely Louisianan environmental justice leaders.

“We were just conservative business owners,” says Theresa. “We understand that there’s a balance. The industry’s important, but it has to be balanced with environmental and health concerns. After SOS we used to hear from industry managers all the time. But they’ve learned that they could adopt a school, do a science program, and work with the Chamber. It becomes dangerous when they aren’t talking to the citizens anymore. I’m just afraid we might be (getting) back to where we were in the beginning.” ExxonMobil Standard Heights' public relations office did not return a call for this story.

The Toxic Tour ends when I drop Willie off at his house. It’s a one-story, century-old bungalow with a tiny front yard full of green horsetail plants and a couple palm trees and an airy porch, its floor and ceiling painted haint blue. Willie is reluctantly retired. His run in the attorney general’s office as the state’s environmental diplomat ended under Attorney General Charles Foti.

About a year into Foti’s reign, in 2005, Willie was guiding two photojournalism students outside the Exxon plant in Standard Heights when they were stopped by Exxon security and Baton Rouge police for trespassing and taking photos. Two weeks later, Willie was fired.

The only hint as to the official nature of Wilma Subra’s office is the Subra Company logo painted onto a white wood panel like a graffiti tag. There's nothing remarkable about the one-story brick ranch house on Old Jeanerette Road. A low, leafy tree canopy shades the backyard leading to Bayou Teche. The blazing midday sun soaks a sugarcane field across the street. New Iberia is a quiet, historic town known mostly for crawfish and seafood restaurants, sugarcane farms and a few plantation homes restored for visitation.

New Iberia is also home to the Gulf South Research Institute, a campus established by the state in an attempt, as Subra says, “to keep smart people from leaving Louisiana.” She was one of the first employees at the New Iberia campus, the center for analytical chemistry and animal studies. They were on the cutting edge of developing protocols for discharge and effluent monitoring and cancer toxicology. Scientists from across the country came to New Iberia to study before moving on to big jobs with labs in less rural settings.

"We worked on quick-response projects with the EPA,” she tells me in her office, which is just a living room with a few long plastic tables linked together, stacks of papers and books piled 2 feet high. A couch, a 20-year-old television and her grandkids’ bright plastic trucks and animals fill the space. Wilma has a sweet voice and calm smile that belie a history of combating large institutions. “We'd get the call from the EPA on, say, a Thursday, and they'd tell us to be ready to sample the air, the water, the soil, the urine, the blood and everything else for specific chemicals," she says. "But we weren't allowed to provide the results to the community. They were given a code number. We gave the results to the agency and the agency gave the community members a summary and it didn't have their data with their number. Over and over I kept seeing this and saying these people really need to understand what this data means. The agencies are not providing them with enough information to make decisions."

Chemist Wilma Subra, MacArthur Foundation "genius award" winner, in her small office in New Iberia.

Subra was part of the response team at Love Canal in the late '70s when a school construction project in upstate New York disturbed a decades-old, 22,000-ton toxic-waste dump. She remembers being in a resident’s house to set up a study and being told by superiors to quickly leave when the residents returned home.

"We were going to sample their home, their yard. And we couldn't interact with them. That was the turning point for me. These people desperately need for someone to help them understand and deal with their situations."

So in 1981 Wilma left the agency job for good. She started Subra Company and she stayed in New Iberia. Now she's a freelance chemist. She teamed up with Willie Fontenot and they traveled to affected sites and talked to residents. Willie worked the political and legal sides and Wilma gathered data, determined toxicology levels, pathology and specific health effects.

In 1999 Wilma was named a MacArthur Genius. Data is her weaponry, and she believes it's useless if passed over the heads of the people on the ground who need it most: people like the Christophers, who watched the Exxon team in their hazmat suits walk off their property with the brown dust samples, never to be heard from again.

"Sometimes the agencies (EPA, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality) come up to me and say, ‘You're creating a situation that we don't have the resources to deal with.’ And that is not acceptable.” Subra says. “The people have a right to be notified and make their own decisions."

“Wilma and Willie were like these mythical unicorns traveling the state together when I got involved,” Marylee Orr tells me. Marylee helped found Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN) in 1986. Formed congruent to the Save Ourselves campaign, LEAN has been the oldest and most represented client of the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, and uniquely local in that they are not affiliated with any national organizations. Like Theresa Robert, Marylee was a mother concerned about her children, especially after her youngest son Michael was born with hyaline disease, a delicate lung defect. Her first fight was a successful petition against a proposal to allow PCB burning in Baton Rouge. She and a small group of women won that battle, formed LEAN and began working with the Wilma and Willie crew.

“There are all these other models for industry to have a voice – the Louisiana Chemical Association (LCA) and Louisiana Oil and Gas Association (LOGA) – but no model for the people to have a voice,” Orr says. A spokesperson for LOGA declined to comment for this piece, citing ongoing litigation.

“We wanted that kind of united front and strength," she says. "We’d meet at our house because I had the kids to take care of. Me, Willie, Wilma, Theresa and some others.”

Now LEAN, like Subra Company, has its office in a plain ranch house in a quiet neighborhood off Florida Avenue. I meet Marylee and her sons Michael and Paul Orr, who both work with LEAN and its partner organization, the Lower Mississippi Riverkeeper. We drive a few blocks down Florida Avenue to La Morenita, a Hispanic grocery store. Before digging into some of the best tacos I’ve ever eaten, Marylee grabs my hand and reaches across the booth for Paul’s. I reach for Michael’s.

“I’m just going to say a quick prayer, if that’s OK,” she says before bowing her head. Marylee is a devout Catholic and attends mass a few times a week. Nothing about LEAN is overtly religious, but Marylee is proud to be the first environmental organization in the country to be funded by the Catholic Church through a grant from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

“We were talking to them about the disproportionate impact on low-income and families of color along the chemical corridor here,” she says. “And they responded. This was before the term ‘environmental justice’ had been coined in academic circles.

“We are the continuity here at this point,” Orr continues. “We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. People come to us with issues in their neighborhoods. We don’t look for problems, they find us. And we are not afraid to litigate.”

“The environmental movement to me before was the typical one – yogurt, backpack, earthy person. But not so much anymore. I’m not that type of person and there’s power in that you can’t be stereotyped anymore.” - Marylee Orr. Michael (left), Marylee and Paul Orr outside the LEAN and Lower Mississippi Riverkeeper office in Baton Rouge.

Marylee reflects on the ’80s and the pioneering work that shifted the don’t-ask, don’t-tell climate that had pervaded industry-state-citizen relations since the Huey Long era. Paralleling the Save Ourselves battle was a similarly important lawsuit in the north Baton Rouge community of Alsen. There, 4,000 residents led by Mary McCastle, a 75-year-old grandma, and with the help of Willie and attorney Steve Irving, sued the toxic waste cleaning company, Rollins Environmental Services. Like SOS, they eventually won in the State Supreme Court, setting a precedent for class action suits against companies for health damages. While SOS gave community residents a voice in the permitting process, the McCastle victory assured people the right to pursue class-action damages against companies discharging illegal levels of toxins into their neighborhoods. Each plaintiff in the McCastle v. Rollins case won upwards of $3,000. These were paltry amounts, but, as attorney Irving says, “We asked for damages in the McCastle case not necessarily to put money into the pockets of residents. It was about making the behavior of the company sufficiently expensive so they would stop doing the bad things that they were doing.”

McCastle and SOS signaled to fence-line communities, made up mostly of low-income people and people of color, that they could speak up against their industrial neighbors. For decades LEAN has been their initial outlet and their best legal advocate. Paul Orr thinks that emerging technology is the next step to put more power in the residents’ hands.

“There are refineries in California that use fence-line monitoring connected to the Internet so residents can look on their cell phones to see, in real time, what the monitors are picking up,” he says.

“It’s too easy for the regulators or industry to dismiss anecdotal info from residents who say they smell bad chemicals,” adds Michael Orr. “They can blame the smell on swamp gas or say you’re sick because you’re eating too much crawfish. If you can analytically quantify something in an objective way with a trusted tool, that’s a different conversation.”

Sometimes down here it can seem like the dry ground is just a bunch of oversized lily pads anchored with trees. In 1980 a 14-inch drill bit on a Texaco oil rig punctured a salt dome under Lake Peigneur in Iberia Parish. A whirlpool sucked barges down like toys in a toilet. The hole reversed the flow of an adjacent canal, drawing in nearby Vermillion Bay and creating Louisiana’s tallest and most fleeting waterfall at 164 feet. Texaco and the Wilson Brothers paid large settlements and the mine was closed in 1986. But memory fades quickly with so much money buried beneath your feet, and since the late ’90s Atlanta-based AGL Resources has been developing Lake Peigneur salt caverns as natural gas reservoirs. But a recent disaster brought the spotlight back to the dubious stability of salt domes.

Bayou Corne, a few dozen miles west of Burnside and The Cabin, is one of the hundreds of narrow bayous of black water weaving through southern Louisiana’s soft mud and hard cypress knees. About 350 people lived in the small development’s Sportsman’s Drive, Jambalaya Street or Sauce Picante Lane.

In June 2012 residents smelled gases, felt occasional ground tremors and noticed bubbles burping out of the bayou. Authorities scrambled to determine the cause until Aug. 3, 2012, when Gov. Bobby Jindal ordered all the residents to evacuate. The company Texas Brine had been storing oil and gas in a salt dome buried under Bayou Corne, and an outer wall of the dome had collapsed, allowing water in and gas out.

It made news, and people clamored for response. The governor ordered buyout packages for residents, and two companies pointed the finger of responsibility at one another. Eventually the 24-hour news cycle moved on to fresher stories, and the Bayou Corne people grew increasingly frustrated and neglected. Then one of the neighborhood leaders made a call to the Ragin’ Cajun.

Ten years ago in New Orleans, U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré stood on the flight deck of the USS Iwo Jima, a few inches taller than President George W. Bush. Honoré, dressed in fatigues with three stars on the bill of his beret, had been named military commander of Joint Task Force Katrina. He came onto the job with a larger-than-life sense of charisma and command. One of the first live news clips of Honoré in action shows him wearing fatigues in the streets of New Orleans yelling, “Put those goddamn weapons down,” to the police and military personnel. Of West Indies and Louisiana Creole heritage, Honoré’s efforts and persona during that crisis earned him the nicknames “Ragin’ Cajun” and the “Black John Wayne.”

Honoré retired from the military in 2008, a living legend in his native southern Louisiana. He was a vocal advocate for an appropriate response following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, but he didn’t dive into the environmental justice game until the phone call from Bayou Corne.

“It had been a year since the (Bayou Corne) accident,” Honoré says, “and the residents were frustrated because in their opinion, they were basically being ignored. I show up, and who do I find? LEAN, Wilma Subra, etc. Within a couple months we did a press conference at the Press Club in Baton Rouge and raised the level of noise a little bit. Then I heard about Mossville so I went there with Marylee and Dr. Subra. Then as we’re in Mossville, we heard about an issue break out in St. Rose. Then Helis Oil and Gas applied to drill in St. Tammany Parish. So we went from an event in Bayou Corne to multiple events, including a fight in the state legislature against them putting a school on a toxic-waste dump site.”

“This is the Southern trilogy, if I may call it that: control the message, control the elected and judiciary government, and scare the hell out of the people.” – retired U.S. Army Lt. General Russel Honoré in the LEAN office.

The General, as Marylee calls him, is as imposing in a sport coat as he was in fatigues. At 6 feet 5 inches, he does not move at a leisurely, retired pace and he does not do small talk, except with Marylee. He calls his organization the Green Army, but both “organization” and “army” are wild overstatements. And he’s not extremely interested in saving pelicans or woodpeckers.

“Down here it’s not conservation,” he says. “It’s a direct affront to people’s health. We’ve got adequate laws; they just don’t enforce them. The Clean Water Act is very clear but the state of Louisiana stopped testing for mercury for 7.5 years under Gov. Jindal.

“If you were to listen to the ruling party, you’d think we had the best economy in the world,” Honoré continues. “So I ask people, if the industry is doing so well for us, do we have the best roads? The best schools? Hospitals? The answer to all of them is we’re either last or second to last to Mississippi, and Mississippi hardly has any oil and gas. We got the largest concentration of pipeline in the U.S., so where’s the money going?”

It’s hard not to imagine a Creole incarnation of Huey Long rising out of the bayou in the form of Lt. Gen. Honoré, whose fire-in-the-belly populism and blue-collar sense of right and wrong comes from a military life, not a Greenpeace manual. Marylee, the General, Wilma and Willie are not screaming for the industry to stop. They aren’t asking executives to take a vow of poverty or for everyday Americans to trade in their SUVs for bicycles. They just want everyone to adhere to the rules, to be open with their neighbors and to clean up after themselves when things go wrong. Lt. Gen. Honoré tries to end on a positive note: “I get glimpses of hope. In the last two months we’ve organized the people and turned two proposals back.”

But the General can’t stop there. “We got nothing done in the last legislature. It was a fiscal session, and the state was broke. We went in for a bill to protect fence-line communities, and in comes a guy from the governor’s office with a little piece of paper with an extravagant number from the Department of Environmental Quality, and he says they don’t have the budget. So it killed our bill before we even got to read it. As we’ve gotten stronger, they’ve gotten more shrewd and crooked.”

On my last day in Baton Rouge I drive Scenic Highway again. Other than a flourish of new apartments near the intersection leading to Southern University, the highway resembles a developing nation spinning its wheels toward the America dream. There’s less polish and facade and more human motion – people walking, on bikes, hanging out on porches and outside of corner stores. At the Exxon fence line, the vivid, exposed street life stops where the empty neighborhood begins.

The size of the plant and its blatant, exposed proximity to the road and people’s lives has already lost the impact it had when I first drove into Standard Heights. I turn on Ontario Street. A couple of kids shoot hoops outside Brunetta Sims’ yellow clapboard house, the plant’s electric fence bordering one side of her yard.

The Sims’ house in Standard Heights shares a property line with the refinery, which recently bought the neighboring church. An electric fence lines the side of their house.

Down the next block, Denise Moore’s small, dark-blue home makes a chain-linked island among the empty grass lots. Moore moved to the house at age 18, and she hasn’t left. Now she shares it with her son, Reggie, an actor and comedian.

Denise Moore has lived in the same house in Standard Heights for most of her life. Like many fence-line residents, the buyout packages are often too cheap to assure that Ms. Moore could buy a decent house in a safe neighborhood. With her job nearby and her working lifespan running thin, she just stays in the house and endures the odors, explosions and respiratory issues.

Exxon offered Denise around $18,000 for her house years ago but she’d have to move into a dangerous neighborhood to get a house at that price. So she stays and keeps her windows closed to the nauseating smells that come at night. An empty grass block away, the Christophers’ house glows yellow and the pit bull lies quietly between two cars.

I turn south, toward the Capitol Building, an orange lighthouse through the trees. At the corner of Chippewa and Daisy Streets where the Exxon fence comes to a corner, I stop at J&S Tire and Service shop. I’ve made a handful of trips into Standard Heights, but this is the first time I get the smell. It hits me as soon as I step out of the car, warm and heavy so you can almost see, cartoon-like, the stream of air being pulled into your body. It smells like photo developer, rotten eggs and backed-up sewage. Jake Spears sits in the driver’s seat of a Chevy truck, its front wheels removed and the hood open. He’s taking a break, eating cashews from a can while his grandson works on a Buick. Jake does mostly tires these days, no longer nimble enough to get deep into the engines.

Jake Spears, owner of J & S Tire and Service shop

Jake bought the shop 14 years ago. There were a lot more houses in the neighborhood back then. He watched the people move out and the houses disappear as cleanly as pieces taken off a chessboardboard game. Jake says he still gets just enough business to stay open. The Burger King and Jack-in-the-Box on Scenic still draw traffic and some business to him.

“When I first come here, they (Exxon) offered me about $35,000 for the shop,” he says. “I said, look at me: I’m not hungry and I’m not completely broke. I bought this place for $80,000. The tools and tires, everything in here belongs to me except that Coke machine. Coca-Cola owns that. I’m 79 years old, but I don’t want to quit. At this age when you sell, you gotta have enough money to relocate or retire, and right now I don’t need to try to rebuy nothing. I’m too old.”

Spears leans back in his chair. The Coke machine hums, and the local news plays on the square television in the corner. His grandson unscrews bolts with an air-compressor wrench. Spears’ eyelids hang low, and the narrow openings glisten with moisture. I think of the smell and the stories of burning eyes and nauseous stomachs. The olfactory sense is so powerful yet so fleeting. I have to actively reconnect with it to again smell the sulfur and chemicals and sewage that slapped me across the face just 20 minutes ago when I stepped out of my car.

Nothing comes easy in places like Standard Heights or St. Rose or Alsen. The streetlights turn yellow then red then green again. The trees lose their leaves then grow them again. The plant lights come on at night, the steam rises, the toxic flares flash, the heavy odor moves through the house like a thin curtain lifted off its rod, the brown dust falls on the cars. Even when you take a second to remember the smell or to see the rusting tanks through the fence, a hundred daily chores come ahead of picking up the slingshot and aiming at Goliath.

“You know yourself,” Spears tell me. “With a big company like Exxon, you can’t fight a case so you gotta go along with them. I’m not down on Exxon because I use their gas, so what can I say? We need it. I wish they could straighten up the odor thing, but I don’t know. The only thing I see, we gotta live with it till we die. I’ll be here till 5. Every day of the week except Sunday.”

I’m reminded of when I asked Michael, Paul and Marylee Orr if their ultimate goal for LEAN was to eventually run out of business. To have no more sick and fearful residents call them about their families and communities being in danger from the plants. Michael sounded a bit like Jake Spears.

“I think the only thing that could put LEAN out of business,” Michael said, “is if you could change the culture of human nature to prioritize health and quality of life above economics. Sounds like a dumb thing to say. It’s kind of like saying when we stop violence we won’t need police. But it’s true. Until then, we’ll keep answering the phones.”