Chatsworth, Georgia

Old Parents, For God's Sake

By Erik Green

The question is inevitable. I hear it every time one of the old folks goes on to Glory and I stand in the receiving line at church back home:

“Now, who are you?”

My response is, more or less, the same every time: “I’m Erik. The baby.”

There is often a pause, followed by a quizzical or, sometimes, whimsical raise of the eyebrow.

“Mhmm.”

A handshake and a nod usually follow, and then they walk on to someone they recognize. It doesn’t bother me anymore because my life has always required a bit of explanation. I was the quintessential “Oops” baby. My parents were settling into middle age with a couple of teenage daughters in the house and, surprise, baby. And this baby had a dark complexion and very black hair. My parents were just regular white folks. Now, you know how it is in the South. Everyone has Cherokee blood, right? Every towheaded Betty Lou is, at minimum, one-quarter Cherokee. It’s amazing how the math always works out like that. So here is my confession: The old folks on my mom’s side insist that we are of Cherokee descent, sprung from Resaca, Georgia — not far from my home now. I also confess that I have no real proof of any of this.

What I do know for sure is that having children later in life is something of a tradition in my family. My paternal grandfather was 56 when my father was born, and my father was 42 when I was born (ahem … foreshadowing). I am one generation removed from the 1800s. My great grandfather fought in the Civil War. This is all well and good, but no one really appreciated my story in elementary school.

“Your parents sure are old. So old.”

Shut up!

“I seen ye Pawpaw this mornin’.”

He’s not my Pawpaw!

This was the exchange I usually had with other redneck kids in school. Most of my friends’ parents were young, and seemingly rich and bon vivant. In reality, they were young. Everything else was smoke and mirrors. The 80s were a time of excess, improvidence and flamboyance. My parents were the opposite of that. Both were devoted Baptists and teetotalers, prudent out of both necessity and piety. A day or two before my dad died in 2008, the doctor asked him how long it had been since he’d gotten new glasses. He had no clue. I can’t recall him getting many new articles of clothing over the years, mostly socks and sweaters at Christmas. He was, truly, not concerned about himself. He learned this kind of selflessness on the farm.

His father was an old man by the time my dad came of age and his older brothers were away in the service. He carried heavy burdens early in life that he never put down. Raising me might have been the heaviest of them all.

My mom grew up in much the same way, the daughter of farmers. She was one of nine surviving children; her father farmed, preached, and worked in a foundry. He stayed up late listening to baseball games during the golden age of radio. Her mother chopped cotton and dipped Bruton snuff. Mom, like dad, worked most of the time. She canned vegetables, made fig preserves, shucked corn, shelled peas, and dried apples on tablecloths under the scintillating sun in the old way.

We had a garden, and I was the mule. My dad hooked me to a plow and I pulled it to and fro, turning over the ground for planting. Imagine the look on my friends’ faces when they rode by on their bikes and saw me in my backward hat and last year’s Reebok Pumps, tromping like a buffalo through the clay. My dad used to tell me that everyone had to have a “gettin’ on place” in order to learn something.

“Until I was 21 years old, I didn’t know how to do anything but smell mule farts,” Dad once said. Working in the garden and hauling hay in the summers were my gettin’ on places. The wisdom gleaned from those experiences didn’t set in until years later, of course.

My life was truly the confluence of generations not normally connected. There were decades missing. There was a cultural deflagration between their generation and mine. I was an MTV kid dropped into Mayberry. It was totally not cool to be me. I was determined that my kids would not have old parents.

I grew up and moved away from my small-town home in Alabama, determined to become a journalist for The New York Times. I started in South Georgia, you know, the logical first step. I focused on my career and visited home when I could. In 2006, I met my future wife and we married in 2007. I was a few hours north of where I began and nowhere near the Big Apple. I was in a small town, much like the one I couldn’t wait to leave. Dad died suddenly the next year, and my mom remains in the same house she’s lived in since they married in the 1950s. They had been married for more than 50 years when dad died. How old-fashioned.

In the subsequent years, my wife and I tried having a baby without success. There was a miscarriage. Possibly another. We were coming to terms with the idea that maybe infertility was in play for us. But I did what any self-respecting Southerner would do: I asked God for help. And I drank a little bit.

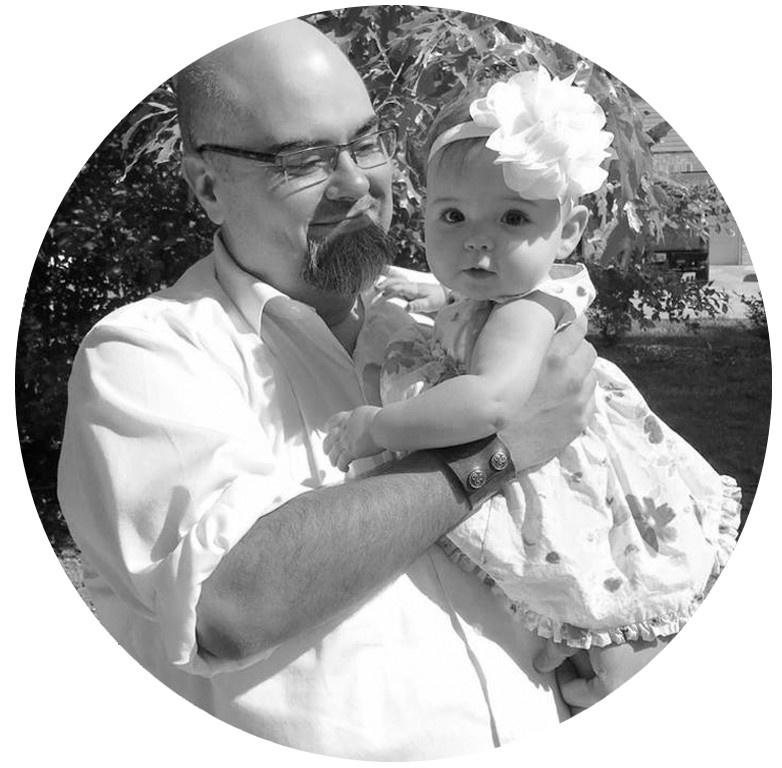

In 2015, after getting into better shape and eating fewer plates of biscuits and gravy, we became pregnant. In October of that year, our baby Wanda Sophia was born. We named her Wanda because both my mother and my wife’s late mother shared the name.

I was 37. My mother was 37 when I was born. My oldest sister was 37 when her son was born. God’s sense of humor is too perfect.

I’m sure I will “pay for my raising” when Sophia comes of age. Maybe her friends will ask her the same questions I was asked. Maybe she’ll wish her parents were younger and less old-fashioned. But in an age in which most of us are disconnected from place, from the land and the soil, I hope she will be able to find a connection to the values and stories shaped by the long memories of old parents. I finally did.