Not long after the death of Pat Conroy, The Bitter Southerner got a call from one of the finest magazine writers

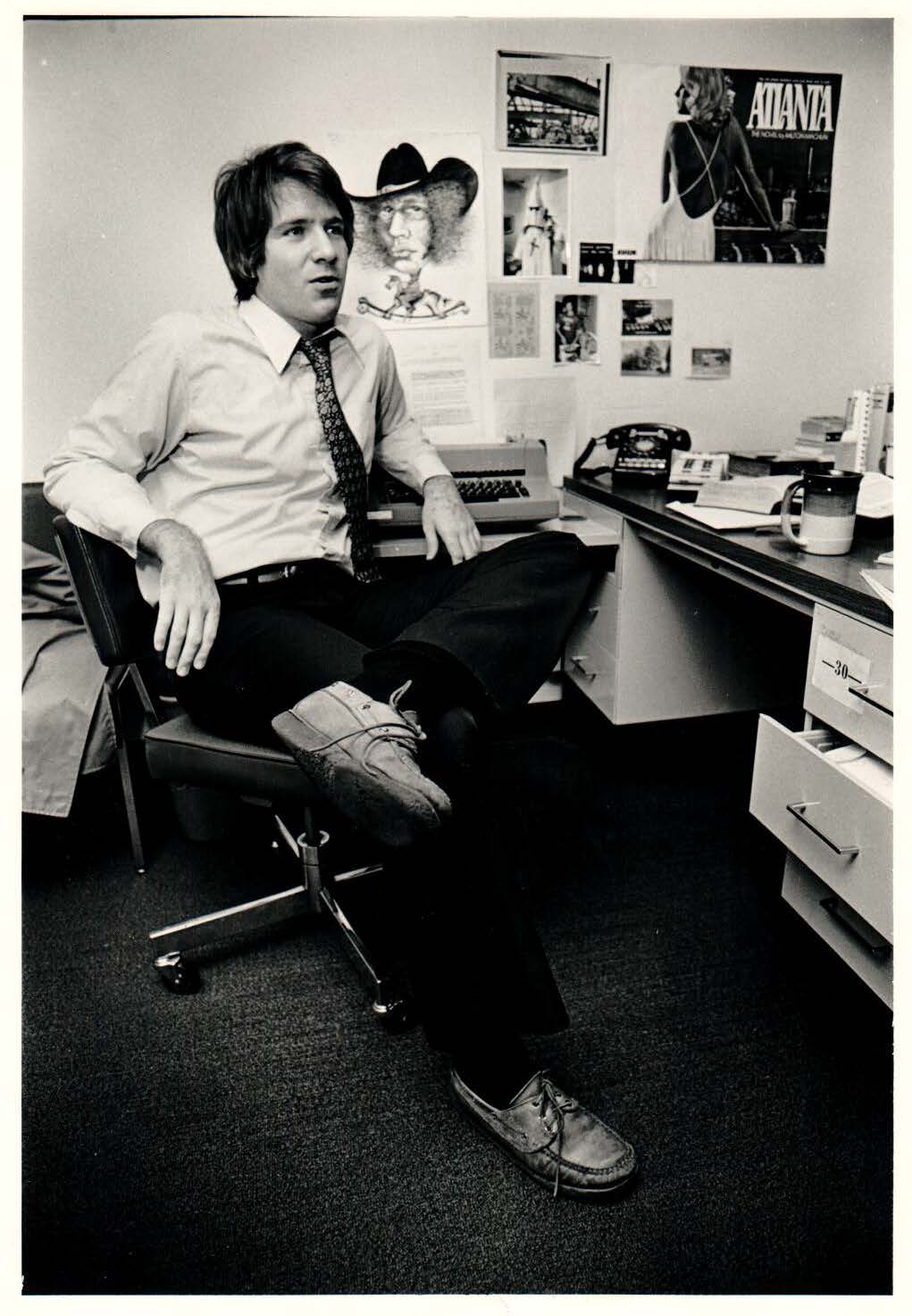

the South ever produced, Steve Oney, who shared a memory from the days when the novelist sat atop Atlanta’s literary elite.

Today, he shares that memory with you.

“Remember the night I couldn’t stop you at the Paideia School? You kept pounding your body into the lane and the ball into the hoop. That’s you. You’re a fighter, bred to it and excellent at it.”

Three weeks before Pat Conroy’s death, I emailed that brief note to him. The author of The Prince of Tides was suffering from pancreatic cancer. Although he vowed to beat the disease and told his publisher that he owed his readers another book, I couldn’t find any realistic grounds for hope. Still, I wanted to give Pat all the encouragement possible and do so in a way that recalled a moment of triumph for him. That I had participated in this moment, and that it had been chastening for me, were more than incidental details. Accompanied by much banter, what had passed between us and the others involved was, at heart, a matter of life and death. Which was why, with Pat in extremis, it seemed urgent to remind him. Not that I thought he’d forgotten. It was the kind of thing you never forget.

The air that November evening was metallic and brisk.

Autumn had come to Atlanta, and with it the leaves had gone brown and the cicadas silent. Set back from Ponce de Leon Avenue on the southern fringes of the Druid Hills neighborhood, the Paideia School (in 1980, just nine years old) was already becoming one of the city’s elite private academies, taking a place alongside Pace, Lovett and Westminster. Not quite as snooty – but snooty enough – Paideia provided a fit venue for an affair of honor between the standard bearers of the literary establishment and a group of young bucks who had thrown down the gauntlet. Besides, a gym with gleaming glass backboards anchored the campus, and it was ours for as long as the business required.

Pat’s team was exactly that – his.

This was not merely because at 35, thanks to his 1976 novel The Great Santini and the 1979 film based on it, featuring Robert Duvall, he was the rising star in Atlanta’s small but impressive constellation of writers. Pat had been an all-state high school basketball player in South Carolina and a starting point guard at the Citadel. Now that the Hollywood money was rolling in, he was thickening around the middle, but he remained a legitimate threat. Equally impressive was Lee Walburn, the longtime public relations and promotions director of the Atlanta Braves before being appointed editor of Atlanta Weekly, the magazine of The Atlanta Journal & Constitution. At six-four and in his early 40s, Lee had been a basketball and baseball phenom in his hometown of LaGrange, Georgia, and played basketball at West Georgia College. Then there was Bernie Schein. The model for Sammy Wertzberger, the flamboyant son of Israel whose family owns the “Jew store” in The Great Santini, Bernie had been Pat’s boyhood pal in their hometown of Beaufort, South Carolina. He was 35, five-eight, and, in appearance, a kind of shambling clown. His idea of proper attire for our epic confrontation was Bermuda shorts, untucked polo shirt, baggy socks and off-the-rack tennis shoes. My initial impression of Bernie was that he’d been invited to participate simply because he knew Pat and because, as a faculty member at Paideia, he had secured the court.

As for their opponents, we were in our mid-20s – old enough to have experienced disappointment and hurt but not old enough to know that sometimes there is no remedy for them. Long-legged and well-muscled, we embraced the youthful delusion that we were answerable to no one but ourselves. Michael Haggerty, the eldest, at 28, had recently moved to Atlanta from Austin. A former lieutenant in the Marine Corps, he was so fast off the dribble that we called him Speedball. Jim Dodson was a droll North Carolinian, whose preferred sport was golf but who knew his way around the hoop and possessed a soft touch.

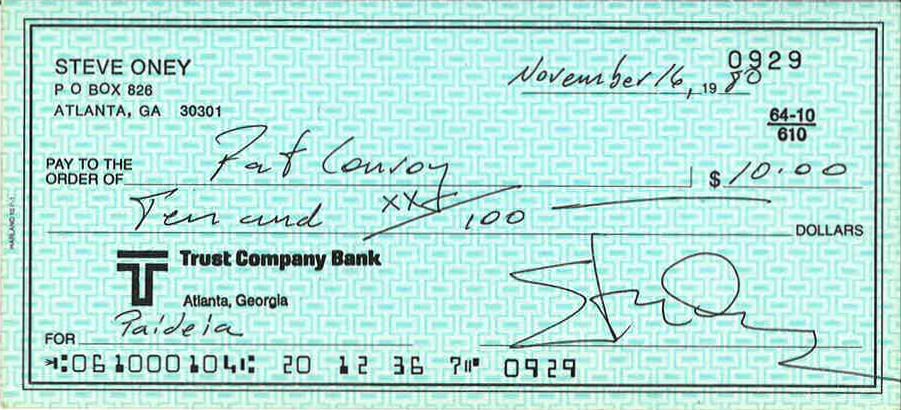

I was 26 and had done much of my growing up in the Atlanta suburbs, where I’d been a mediocre reserve center for the Peachtree High School Patriots. But thanks to graduate-level courses on asphalt and concrete, I’d become a dangerous streak shooter. What we had in common was not just our youth: We were all staff writers at Atlanta Weekly, which made us potential usurpers to the throne. While the Weekly had been founded in 1912 as The Atlanta Journal Magazine (Margaret Mitchell worked there in the 1920s), it had drifted along in sleepy irrelevance until 1979, when Nancy Faye Smith, Lee’s predecessor and a Texas Monthly alumna, gave it a makeover and a mission. We interpreted this as carte blanche to question authority.

ARCHIVAL ATLANTA WEEKLY

ARCHIVAL ATLANTA WEEKLY

During warm-ups, as I drained midrange jumpers and Pat and his teammates stretched and practiced layups, the Paideia gym began to fill with Atlanta’s literati.

Anne Rivers Siddons, author of the novel Heartbreak Hotel, was there, along with Heyward, her dapper, advertising executive husband. So, too, was short-story-writer Paul Darcy Boles, in an ascot and Brooks Brothers blazer a refugee from an already extinct world where one could make a handsome living peddling 5,000-word morality plays to The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s. Michele Ross Baird, the lovely book editor of The Atlanta Journal & Constitution, was on the sidelines, as was Cliff Graubart, proprietor of The Old New York Book Shop on Juniper Street. The city’s writing community revolved around Cliff’s store, which sprawled through a rambling, craftsman house. He sold valuable first editions as well as used paperbacks, and whenever authors within a hundred-mile radius published new works, he gave parties that lasted long into the night. This was tout le monde, and except for my University of Georgia roommate Frazier Moore, who was freelancing and was there too, it was Pat’s crowd.

Frazier Moore and Steve oney

Not that this was surprising, for the person in attendance who drew the most attention – the person, in fact, the games were for – was a sainted figure to the old order: Jim Townsend. The best literary editor in town, Jim was the paterfamilias to a generation of Southern writers. He was also dying of cancer. Only 47, chemotherapy had left his skin ashen and robbed him of his hair. Age, youth and bragging rights were on the line, but as Pat had for weeks been telling anyone who’d listen: “We’re going to win this for Jim.”

It all had started a month earlier during a gala yet sobering affair at the Marcel Breuer-designed downtown Atlanta Public Library, which had recently replaced the battered but beloved Carnegie Library and was thus another symbol, as if the city needed more, of the New South.

The occasion, which Pat had organized and would emcee, was intended to give Jim Townsend a resounding send-off while he was still healthy enough to enjoy it. The attendees included most of those who would later congregate at Paideia and also such journalists as Marshall Frady, Paul Hemphill and William Hedgepeth, the novelist Terry Kay, a cross section of local business and political leaders, and even a coltish Newt Gingrich, who’d recently been elected to Congress from an outlying district.

That the turnout was big and cut across so many layers of Atlanta society was a testament to the guest of honor. A native of Lanett, Alabama, James Lavelle Townsend had founded Atlanta magazine in 1961. He had run it on and off for 10 years (there were also sojourns at the helms of publications in New Orleans and Charlotte), a period that encompassed the mayoralties of Waspy Ivan Allen Jr., Jewish Sam Massell and then incumbent Maynard Jackson, the inaugural black. During Townsend’s editorship, the city had sailed largely unscathed through the racial travails that bedeviled the rest of the South, and he deserved some of the credit – not because he was a great thinker or tactician but because he was a great believer, and the object of his belief was Atlanta. He believed in the city’s future. He believed in its progressive mythology. He believed in its architects and developers. His organ for expressing that belief was Atlanta, and he filled the magazine with the work of those people in whom he believed most – the city’s writers, artists and photographers. By the sheer force of his conviction he made them believe in themselves. In a time of possibility in Atlanta, Townsend had been a vendor of dreams.

Sadly, however, Townsend’s future was now behind him. In need of comprehensive medical benefits, he was spending his final months at the Atlanta Weekly offices in the 72-Marietta-Street headquarters of the Journal & Constitution. There, at a desk next to mine, he wrote a column called “Dear Heart.” The pieces, most of them homages to the simple pleasures of his Alabama childhood, were by turns humorous and warm and always winning (the best were collected into a book) – and I was part of them. On the day the art director scheduled the photo shoot for the logo – an image of fingers flying over a manual typewriter keyboard – Jim went home sick. I posed for the picture. For the 575,000 subscribers who received Atlanta Weekly in their Sunday newspapers, I was the hands of Dear Heart.

During a long cocktail hour that preceded the Townsend fete, Jim Dodson and I got into a conversation with Pat Conroy and Lee Walburn about basketball.

We young Weekly staffers had been playing almost nightly at the Luckie Street YMCA around the corner from 72 Marietta, and we were not shy about our prowess. For some time, in fact, the idea had been in the air that we might get up a friendly game with these aging college stalwarts to see if they could still put on a jockstrap — just for fun, it was understood. We had always left it there, and that’s where we again left it before the event began. But that’s not where it remained. All that was needed to transform this notion into reality was provocation, and as anyone who has attended a wake for the living can confirm, they are fraught with opportunities for provocation – especially when the speeches start.

After the assembled group took seats in a library conference room around a scattering of tables with Townsend at the head, Pat began soliciting testimonials. As is typical of such things, the speakers to a one sang Jim’s praises – as well they should have. But after the sixth or seventh encomium, the atmosphere grew heavy. Overuse of the words genius, creative, brilliant and nurturing has a way of casting a pall. For his part, Jim was thanking and hugging people when they finished, and he seemed touched. Still, it felt as if the crowd was burying him alive, so when Pat nodded at me, I made the ill-advised decision to say something original. It was a privilege to sit beside this revered editor at Atlanta Weekly, I began. I was receiving a priceless education in writing. But – and here I stepped through the ice – what I found most remarkable about Jim was how he managed to get so much work done while spending most of his time on the telephone sweet-talking literary ladies from across the South who knew him from his years at Atlanta magazine. This struck me as an innocent deviation from accepted doctrine. Not only that, but it was true and flattering to Jim – he remained devilishly among the living. The lone place such a comment might not fly, I thought, would be in church. The coughs and whispers that greeted my stab at irreverent humor told me that church was exactly where we were. Worse, Pat took umbrage.

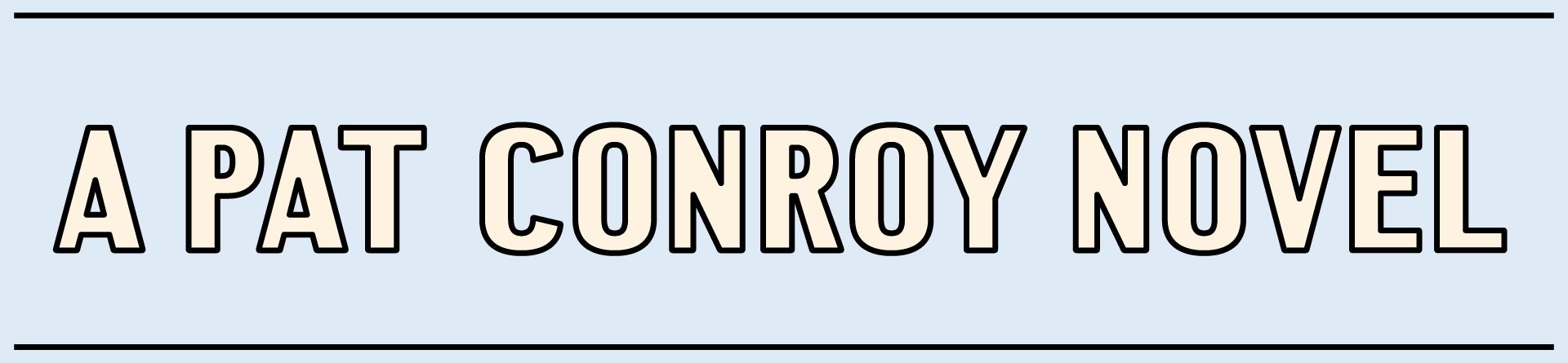

Pat, of course, was one of the all-time umbrage takers in American literature. His heroes frequently use grievance to uphold virtue. (See Meechum, Ben; in The Great Santini.) By the same token they abhor piety, especially as embodied by institutions. (See McLean, Will; in The Lords of Discipline.) Pat’s ability to negotiate the contradictions between these poles was one of his great literary strengths and one of the elements that makes his fiction Southern. (Is there any other part of the country whose people are so simultaneously devout and incorrigible?) Unfortunately, Pat saw me on this night as a defamer, not a sprite, and he would call me to task. Once the program concluded, he, I and various seconds began negotiating terms in an unintentional parody of the code duello. Our teams would meet in a best-out-of-three, half-court basketball tournament, all games to 11, one-point buckets, win by two. We agreed upon Paideia as the site. As for the stakes, they would be $10 per participant, payable by each member of the losing team to his winning counterpart. Not serious money, but sufficient to add a sporting element.

The opening game was all about defense, both by those who could play it and those who could not – and Pat, who would guard me the entire evening, could play it.

While I had been taking those flashy jumpers prior to the onset of hostilities, he had been studying my tendencies. What he saw was that at six-three with a high release point on my shot, I could, if unchecked, soar over the top of his six-foot frame at will. Which was why, on the initial occasion that our team got the ball, Pat not only bodied up on me but began slapping my wrists and grabbing my elbows. It was like the worst first date ever. From my preferred, high-post position, I would fake to the inside, pivot back out, then sprint to a corner, where I was typically deadly. But there was Pat, staying with me, stride for stride, keeping my arms pinned to my torso. I couldn’t have caught a pass, no matter how well thrown. As if this weren’t enough, Pat also worked me in the midsection. All shooters are vulnerable there, but on this night I was more so than most. A few weeks earlier, a girlfriend had dumped me by figuratively sticking a shiv into my heart and raking it down to my testicles. Pat didn’t know this, but having grown up the son of Marine Corps Col. Donald Conroy – aka the Great Santini – he was a student of pain and sensed where it resided in others. So he continued to hammer. Had this been a friendly game, I would have called a foul, but from the start it was clear that unless someone slammed you to the floor, there would be no fouls this evening. No quarter would be given, none asked.

Luckily for us, what Pat tooketh away Bernie Schein gaveth back. Bernie, who guarded Michael Haggerty, was a slacker on defense. On top of that, he couldn’t comprehend a fundamental truth about Michael as an athlete – he was left-handed. Bernie kept overplaying him to his right, which meant that Michael was able to blow past him time and again for uncontested layups. Thanks to that and several crisp jumpers by Jim Dodson, we won this one, but only by a couple of points. As soon as it was over, Pat, gasping for breath, burst through the heavy doors that gave onto the parking lot. He was on the verge of collapse, but as the breeze from outside rushed in, I was more concerned about us. While we’d drawn first blood, we were in trouble. Our opponents were playing with greater resolve.

Only a few seconds into the second game it hit us that Bernie Schein, far from being a schlub, was a stone cold killer, a sniper in camouflage.

Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang – he sank three, four, five consecutive jumpers. Pat set up each shot by laying shuddering screens on Michael that freed Bernie 20 feet from the hole and forced me to chase him out there. Every time, I arrived a second too late, and a second was enough for him. Bernie may have looked like a clown, but it was in the same way that the great Harlem Globetrotter Meadowlark Lemon did. He was for real. More crucial, he and Pat had been playing together since they were teenagers, and Pat – ever the point guard – knew how to get the ball to his buddy. With Bernie on fire and Lee Walburn sticking in putbacks on the few occasions when Bernie missed, Pat’s guys won going away. Yet here again, they were the ones who afterward seemed out on their feet. Bernie’s wife, fearful that he might have a heart attack, waded into their midst to suggest that we should just end things as a draw. That wasn’t going to happen. What had been implicit in the buildup now was explicit. This was war. As I waited for the finale to begin, I let my eyes wander the sidelines, where they landed on the figure of Jim Townsend. He was having a terrific time, but he appeared so ghostly gray that I averted my gaze. I then stared at Michele Ross Baird. She was among the most beautiful women I knew – and she loved books. There it was. Thanatos and Eros were in the house, just as they are in every house, and always have been and will be. These games may have been for Townsend, but they were about coming to terms with mortality.

The end was brutal, but it could have been no other way.

We were now playing for keeps. In an effort to shut down their main scorer, I guarded Bernie Schein, the theory being that with my seven-inch height advantage I’d smother him. The strategy didn’t work, because Pat kept setting solid screens for his old friend. Worse, in order for me to match up on Bernie, Jim took Pat, and Michael took Lee. There was serious animosity between Michael and Lee stemming from Michael’s resentment that Lee had replaced Nancy Faye Smith, who’d recruited Michael from Texas Monthly. The two promptly tangled. Lee maintained that Michael kneed him in the groin. I missed that, but I did see him elbow Lee in the head. Once again, no fouls. This was how it would go as we exchanged leads, fighting down to the finish. With our opponents up 10-9, Lee grabbed a rebound and whipped the ball to Pat. We knew what to look for, so we collapsed on Bernie. But Pat, rather than pass to him, faked, turned, and drove to the basket. The fake gave him a half-step on Jim, and a half-step is all an ex-college athlete needs. Pat was gone, exploding to the rim, and laying in the shot. It was like something out of a Pat Conroy novel: The old men had prevailed over the young bucks.

If there was celebration, I do not remember it.

If there was commiseration, I did not partake. I threw on a Georgia Bulldogs sweatshirt and drove downtown to the Atlanta Weekly office. I always felt at home there, especially after hours, when it was empty and I could write in peace. Although I had work this night on a story due later in the week, I ended up just sitting. As much as the loss stung, I appreciated that the victory by Pat’s team over ours was dramatically satisfying and morally right. How could you not root for them? They were the underdogs, and we were cocky. They played for something bigger than themselves. We had it coming, and they gave it to us. They taught us a lesson: You can’t win them all. This world will humble you. I wrote Pat a check and stuck it in an envelope.

As it turned out, Pat later had his own thoughts about the general topic of defeat, and he expressed them in My Losing Season, his fine, 2002 nonfiction book about his basketball career at the Citadel, which saw his team whipped way too many times. He wrote:

“Loss is a fierce … uncompromising teacher, coldhearted but clear-eyed in its understanding that life is more dilemma than game, and more trial than free pass. My acquaintance with loss has sustained me when … despair caught up …”

This is true.

STEVE ONEY, ATLANTA WEEKLY, 1980

Yet I don’t believe Pat, who over the decades did me literary favors and with whom I stayed in friendly contact, viewed life as a tragedy – and as my last email to him suggested, I no longer think the moral of what occurred at Paideia involves loss. After Pat’s funeral, I phoned Bernie Schein, who now resides back in Beaufort, where Pat lived at the end. “Those games were as important as hell to Pat,” Bernie said of our tournament. “There wasn’t a year that went by that we didn’t talk about them.” Bernie’s remarks confirmed my evolving view. Pat’s team hadn’t shown us how to lose. They had shown us how to win. Jim Townsend’s generation is mostly gone. (The hands of dear hearts could not hold them.) Pat’s generation is going. Mine is getting ready. It doesn’t stop. But there are moments – the Atlanta shootout was one; and, by God, Townsend’s dying flirtations another – where grit and gumption buy us an extra round of what hoopsters call hang time. We rise above the floor and for an instant float. Soon, gravity pulls us to the earth then puts us under it. But for a second we are up there. Such moments are what matter, never more so than when age and fate begin to circle.

Steve Oney is the author of And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank.

He is writing a narrative history of National Public Radio for Simon & Schuster.