EDITOR’S NOTE: The seed of this story, for North Carolina novelist Taylor Brown, was planted on August 12, 2017, when the so-called “Unite the Right” rally turned deadly in Charlottesville, Virginia. For Brown, Charlottesville summoned echoes of another deadly Southern conflict, from almost a century ago — the Battle of Blair Mountain. “The average person has never heard of the Battle of Blair Mountain,” Brown told us. But he knew the history well because writer Jason Frye, his longtime collaborator, grew up in Logan County, West Virginia, where the battle happened. “When Jason was a kid, instead of looking for arrowheads, they'd be looking for bullet casings. They fired a million rounds at the Battle of Blair Mountain.”

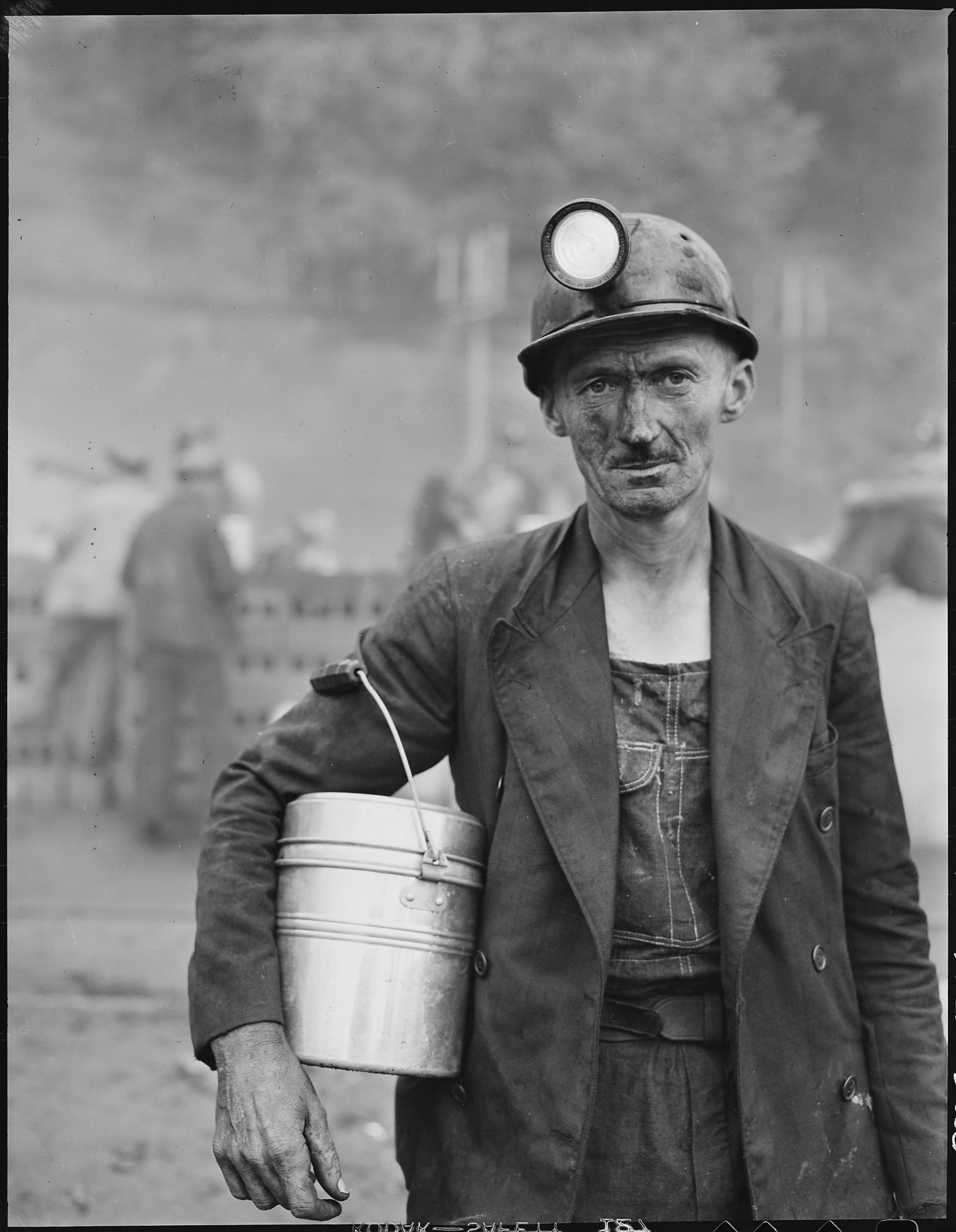

In that 1921 battle, 10,000 mine workers took up arms against 3,000 policemen and strikebreakers whose directive was to break the workers’ union. The battle ended only after President Warren G. Harding sent in the U.S. Army. The workers — a vast mix of white folks, African-Americans, Poles, Italians, and other immigrants — had no uniforms, save for one article. They all wore red bandanas. Herewith, we bring you a piece of fiction, in a historical setting, that feels, somehow, as relevant as the news.

The boy at the table wore a red bandana around his neck, a pair of black-framed eyeglasses, and a camouflage ball cap with the number “3” stitched on the crown. He was thumb-scrolling on his smartphone when Johnny walked up. A drop cloth had been draped over the table, the fabric scrawled with slogans:

Impeach Intolerance.

John Brown Lives.

Get Some, Love.

The painted black silhouette of a rifle lay across the tabletop, as if for sale.

Johnny stood looking at the table. He could hear the whine of the Ferris wheel behind him, spinning in the fairground dusk. The skeletal groans of rusty carnival rides haunted the air, like ancient industrial contraptions. It was late summer and he wore a yellow mesh football jersey numbered “00” — double-aught. He wiggled his belt buckle with one hand and crossed his legs where he stood, tipping the steel toe of one mustard-colored boot in the grass. He scratched his chin.

“I’ll bite,” he said.

The boy in the red neckerchief looked up. One of his eyeglass lenses was patched black.

“How do you feel about Nazis?”

Johnny stiffened, raising his yellow-fuzzed chin.

“How the fuck do you think I feel?”

“Just a question.”

Johnny rubbed his thumb across his yellow stubble, a rasping sound.

“My granddaddy bagged them in ’44,” he said. “My hero growing up.”

“What about the Ku Klux Klan?”

Johnny thought of white knights on sheeted horses, circling the burning death-trees of Christ. He thought of the new flood of them on his television set, marching in file, wearing blood-red crosses over their hearts. He thought of what he’d found in the back of his grandparents’ closet, playing hide-and-go-seek as a boy.

He leaned and spat through his teeth.

“They make me ashamed.”

The one-eyed boy nodded slowly, uncrossing his arms.

“Would you call yourself a redneck?”

Johnny clenched his ass, bouncing the dip can in his back pocket.

“I got tendencies.”

“You know where the term redneck comes from?”

“Working in the fields. Sunburn.”

The one-eyed boy set his elbows on the table.

“Wrong. Let me tell you a story.”

Sid Hatfield, kin to Devil Anse, stood on the plank porch of the hardware store, his palms set casual over the curved handles of his double-action revolvers. He was the 10th child of 12. One of nine who survived. The badge over his heart read MATEWAN POLICE, with the number “1” stamped between an eagle’s wings.

Chief.

His head was shaved over his ears, his hair grown spiky from the crown of his skull. His tie was wide and flat and short, decorated with paisleys. Thirteen men stood in the muddy street before him. Men of the Baldwin-Felts agency, with hard faces and city-cut suits. Some cradled self-loading rifles disguised in butcher paper, like cruel bouquets, while others held their gun hands inside their coats like upstart Napoleons, grasping the curved handles of revolvers. They pushed their bellies with pride against their belts.

Sid smiled.

He had dug the black veins of West Virginia coal that made rich the companies that hired these men. Money that could buy mansions on the shores of cold, clear lakes and 12-cylinder Italian automobiles and murder in muddy streets behind the gleaming badges of private detectives’ agencies. Coal money, God-strong in Mingo County. Sid smiled because he was risen from the mud of this place, born to meet mean men in the streets.

The mayor, standing beside him, squinted at the warrant produced by the Baldwin-Felts agents. A misty rain was falling, slanted and feathery, tickling the shoulders of their suits. Tiny bright pearls in the wool. Sid knew these men in the street had warred for their country in trenched hells of mud, killing Krauts with machine guns and grenades and their bare hands. He also knew they were aliens in this place, in these jagged dark shadows between the hills of his birth. Sid stepped slightly back into the door frame, feeling the darkness drip down his face.

The agents had arrived on the Number 29 train that morning. They were there to evict of the families of miners on strike, to turn them out into the streets. They had done this at gunpoint, hurling dresses and bedsheets into the mud, and then they had come for Sid himself, the Chief of Police, a man known to defend the unions. Sid knew the rifles of miners had followed every act of these scenes, hidden in the trees, and he knew they were perched now from windows and doorways and alleys, waiting. In the distance, the whistle of the 5:15 train, carrying the promise of arrest warrants for the detectives from the county seat.

Sid Hatfield knew right where he was, and he was not afraid.

There was such deep, dark promise in hide-and-seek, the secret crannies of homes and rooms you thought you knew. Johnny liked to hear the thrum of secrecy in his ears, the black groan of pantries and eaves. There were the bright rooms of the house, with their lace tablecloths and ebony legs and heirloom rugs, their crosses and portraits on the walls, and there were the offstage spaces, like the closets and attic and laundry room. There were caves under antique desks and whole dim rooms beneath the skirts of dining room tables. There was the narrow dark corridor inside his grandparents’ coat closet, between the shoulders of the coats and the wall.

Johnny’s cousin, Evette — 10 years old, too — was counting out loud from the sunken floor of the den, watched by the heads of mule deer and javelina that hung bodiless from the walls. There was no television in the room. Only a brick fireplace, with the blue hiss of gas flame to ignite the logs.

Cowboy TV, his grandfather called it.

Johnny wore only his socks, to make his steps soft on the stairs. He mounted them on all-fours, silent as a housecat. His siblings and cousins were spreading throughout the house, aiming for their secret cubbies. His grandparents were out on the sleeping porch, dozing with oxygen tubes hanging from their noses. His grandfather was so small now. Perhaps 110 pounds. He had always been short, less than five-and-a-half feet tall, but wide and stout. He had worn the raked cap and parachute wings of an Airborne Ranger. He had a Luger taken from the body of a German officer — a pistol which, if you believed the Indiana Jones movie, could shoot through six men in a row, and which the old man let them hold every Christmas Eve. He had owned Ford dealerships after the war, whole fleets of sedans and station wagons multiplying beneath him like vast heads of cattle.

Now, Johnny reached the top of the stairs, steering himself into the master bedroom. His cousin’s counting echoed in his wake. He passed his grandparents’ bed, which hovered high from the burgundy carpet, with a step stool to aid their quivering climb each night. He turned into their walk-in closet and slipped sidewise between the hanging coats and shirts on his grandfather’s side. There were starched collars in an array of colors, arranged in gradients, and tweed jackets and pinstripes. There were seersucker and linen, and satiny leisure suits kept in the cellophane of the dry cleaner for decades.

Deeper, there was the heavy olive wool of his dress uniform, with the screaming eagle of the 101st Airborne on the shoulder. The same badge stitched on the old man’s jumpsuit when he leapt into the dark over Normandy in 1944. The bald eagle screamed in the dark of the closet, as always. That American scream.

Next came the white bunny costume, which he always wore at the dealership the week of Easter, and the gorilla suit for Halloween, and the Santa suit he wore on the showroom floor when he was a stouter man, taking the children of the county on his knee, no matter if their parents were the sorriest of tire-kickers. Some of the children each year received items mail-delivered to their doorsteps, with only The North Pole for a return address.

Johnny’s boyhood fingers traced along these rowed sleeves, the many stripes of his grandfather’s life. He continued deeper into the closet, away from the dull light of the bedroom. Evette had caught him here before, so he had to push farther through the shoulders this time, deeper into the crowd of coats. The smell of mothballs filled his nose. He wanted Evette to find him in the deepest corner of the closet, the darkest, where she would grope for him, like she always did. Her hand fluttering between his legs. Their lips brushing in the dark, when Johnny could imagine his cousin was one of the boys from school.

Near the back of the closet, deeper than he’d ever explored, hung the white shape of a robe, like a priest or wizard might wear. Johnny touched the sleeve. The material was satiny, like something that could glow. In the back corner, hidden behind the coats, stood a tall wicker basket. Johnny knelt, removing the lid.

“You’re shitting me,” said the mayor. “This arrest warrant is bogus.”

Sid knew it would be. He had leaned back farther into the shadow of the hardware store. The butts of his pistols glowed like skillet handles beneath his hands.

The detectives in the street smiled, hard-faced, like it was all a joke. Then their leader, Albert Felts, reached into his coat — or so Sid would tell the jury later. Albert Felts, who boasted that he would break the unions of West Virginia even if he had to send a hundred men to hell.

He would go first.

Sid’s pistols fairly leapt from his belt, one after the next, and he shot Albert Felts through the brain. The other agents were dropping to one-kneed shooting positions, drawing their guns, when the rifles of the miners cracked from the trees, setting them tumbling and screaming, dying in the street. The men turned and fled, and Sid stepped from the porch, walking after them, his pistols barking again and again at the ends of his hands, like the mouths of dogs.

National Guard troops sent to "keep order" in the coal miners’ strike.

When his grandfather died, Johnny did not drive to the hospital to meet the rest of the family. Instead, he excused himself from his art history class and drove his truck straight from campus to his grandparents’ house, which he knew would be empty now. He forced the back door and walked down the hall, the place as quiet as a museum. He stomped up the ashy wood of the stairs and into the back of the closet and retrieved the wicker basket, still there these years later, and brought it out into the yard.

It would be winter soon, and his breath smoked in the air. He arranged three pieces of wood in the shallow drum of the firepit and sprayed them down with lighter fluid and struck a match. The flames rose, spitting and cracking and bright. When they had risen as high as his waist, Johnny removed the top of the basket and lifted out the white hood and set it on the fire grate. A capirote, he knew, like those worn by the secret brotherhoods of Spanish saints. The eyeholes were cut sightless and dark, like for a Halloween costume. The white hood shriveled and twisted in the fire, blackening, as if wizening into a more spiritual form. At the last moment, the death’s head seemed to leer at him, as if knowing his deepest sins, before collapsing through the grate.

Skirmishes up and down the Tug River Valley. Martial law. Miners arrested for reading union journals while the hired gun thugs of big coal walk free. Two Gun Sid Hatfield, the Terror of the Tug, is photographed with Mother Jones, legend of the United Mine Workers. In the ashy grain of the photograph, his head is cocked slightly over his tailored suit, his face cut hard and sharp, his killer’s eyes aimed far over the photographer’s shoulder, as if watching a distant ridgeline. He does smile. He has turned the jewelry store into a gun shop.

Sid hatfield, brandishing one of his famous pistols

Armed men are living in the hills now, ex-miners who refuse to sign the yellow-dog contracts of the coal companies. They paint their faces with ash and carry their new hunting rifles, watching mine operations and army convoys from hidden perches. They whisper in English and Polish and Italian. Meanwhile, hired mine guards stand high upon the coal tipples, as upon the parapets of tin-walled castles, armed with high-powered rifles and telescopic sights.

War, building like methane in the chamber of a mine.

On August 1, 1921, Two Gun Sid, friend of the mining man, is gunned down on the steps of the neighboring county’s courthouse. He is unarmed at the time, standing next to his wife, shot 15 times before his body hits the steps. The shooters — known members of the Baldwin-Felts agency — are not arrested by local deputies.

“The most glaring and outrageous expression of contempt for law that has ever stained the history of West Virginia.”

—The Wheeling Intelligencer

“Murdered by the hired gunmen and assassins of the coal barons.”

—Illinois miners’ union

“Is it any wonder that even the heavens weep?”

—United Mine Workers attorney, speaking in the rain at Hatfield’s burial

Blood, bright as a spark on the courthouse steps.

The miners are coming down from the hills, rising up out of the ground. They are marching toward Mingo County, where Sid Hatfield was sheriff. Blair Mountain, West Virginia, stands in their way. They have knotted red bandanas around their necks, as if their throats have already been cut.

Blair Mountain “redneck” coal miners

Johnny set one boot over the other, cocking his hip.

“How do I get one?”

The boy in the red bandana crossed his arms.

“We are against racism. Also fascists, Nazis, misogynists, homophobes, and the predatory economic and social systems of the rich elite. You join us.”

Johnny swiveled slightly over his crossed legs, feeling the bulbs of muscle that dripped beneath the feathery hems of his cutoff shorts.

“Which entails what, exactly?”

The one-eyed boy smiled, casting his eyes at the black rifle silhouetted on the table.

* * *

Johnny sits outside a cafe on Bull Street in downtown Savannah, his iced coffee sweating on the small round tabletop. In his lap, a piece from his forthcoming installation. It is, unmistakably, the head of an American alligator — Alligator mississippiensis — shaped from the woven wire of an old crab trap. He works with pliers and tin-snips, twisting and pulling and cutting, as if to catch the spirit of the beast in a net of metal. He will cover this thin armature in lantern paper, planting a white LED light beneath the skin. The skull of a dinosaur, ghost-bright, fractured by the insidious latticework of the trap. He is creating a whole bestiary of the coast, a glowing boneyard of the dead and disappearing, the snared and netted and trapped. Sea turtles and sturgeon and swallow-tailed kites. Panthers and gators and the sweet sea dogs of manatee. “Ghosts of the Southern Eden.”

Johnny’s phone rattles on the tabletop.

Noon.

He takes the skull of the reptile under his arm and starts walking toward Forsyth Park.

They are twin-engine Martin bombers, built in 1918. Biplanes with open cockpits. The bombs are of similar vintage, surplus munitions of the Great War that ended three years ago. President Harding has sent up the planes. They lumber low over the hollers around Blair Mountain, big as prehistoric dragonflies. For now, they drop leaflets, like strange weather, which forbid insurrection. The airmen have been told to look for red bandanas through the trees.

Johnny drives a ’66 Ford pickup, the rusty patina glazed timeless beneath a clear coat of urethane. A truck wearing the camouflage of a post-industrial wasteland, perfect for blending against an abandoned pulp mill or chemical plant. Beneath the hood is a 289 V8, which Johnny rebuilt with his own hands, using online videos and an arsenal of hand tools that he inherited from his grandfather — a man who died unable to speak to him.

The old man had lain there in his hospice bed, sweating with fear, as if his grandson’s sexuality were contagious. As if Johnny carried some plague or curse into the room, which could turn a 90-year-old man queer, damning him at last. Johnny can remember his grandfather licking his lips and shaking and stammering, trying to find something to say.

Sometimes, Johnny can believe the old man was afraid of something else: what his grandson would find, after his death, in the wicker basket in the back of the closet.

That he was ashamed.

Johnny sets the alligator skull in the bed of his truck and unlocks the toolbox, where he keeps his gun.

Blair Mountain miners turning in their guns

Gas and incendiary bombs, dropped on West Virginia from hired planes. A first for the republic, bombing itself from the air. One of the bombs will bury itself deep in Blair Mountain, unexploded. A trove of proof. Gun battles for a week, sporadic, crackling like belts of firecrackers through the hills. More than a hundred men will die, most of them miners. A thousand more will be arrested, some not paroled for years. The Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest land battle on the continent since the Civil War. The shell casings of the battle will be found for decades to come, stored like arrowheads in trifle boxes or junk drawers or cubbyholes. Few in museums. The miners submit, finally, before the threat of federal troops. They hide their arms in hollow trees and stump holes and rocky fissures — in hundreds of secret caches—and come down from Blair Mountain. They are Americans, Italians, Poles. One in five is black. They will be called anarchists, communists, insurrectionists.

Rednecks.

They have lost their fight with big coal and the federal government.

The bronze soldier in Forsyth Park faces north, toward his old enemy. His face is hollow, his beard long and sharp. His hands are clasped at his waist, like a man at church. A long musket leans against his shoulder, the bayonet raked high beside his ear. He stands on a base of Nova Scotia sandstone, which bears winged angels at each corner and the single carving of a war widow grieving beneath a willow tree. The soldier does not seem to notice the motley crowd gathered beneath him. Their signs hover like thin shields, raised against the Nazi Party and the Ku Klux Klan and other white power groups assembled for their rally in town. The counter-protesters have surrounded the iron fence of the monument in ragged halo, trying to unite their voices for a hymn.

Johnny stands beneath an elm tree at a small distance, his back to the crowd. He is a Georgia Weapons Carry License holder, which allows him to carry a long gun openly in a city park. The black rifle hangs across his chest on a sling, his forearms crossed casually over the butt end. He wears a red bandana from his neck. His detail is security. He squints down the long green field of the park, toward the tennis courts at the far end. He wears polarized sunglasses, like he did during his long afternoons in the desert, when the heat rose like gasoline fumes from the pavement and every dusty sedan seemed ready to blow. When he questioned, again and again, the wisdom of trying to prove himself to the dead. His grandfather. Those long afternoons, when he wondered whether his silence was cowardice or courage.

Don’t ask...

The marchers are forming along the fence of the tennis courts now. Many wear the glory suits of the Klan, steepled white, the hoods pulled up to show their shouting red faces. Some carry Nazi flags or Southern crosses, like the battle standards of old times. They are moving together now, marching, arrayed like a phalanx on the field.

Mother Jones, the “grandmother of all agitators” — so-called on the floor of the United States Senate itself — had tried to stop the miners’ march on Blair Mountain. She had stood before their motley ranks, waving a roll of paper in her hand. A telegram from President Harding, she said. A promise to rid West Virginia of the gun thugs of big coal, who haunted their homes and streets, evicting families and shooting strikers, breaking the back of the unions. Men like the Baldwin-Felts agents, who attacked tent colonies and striking workers with the “Bull Moose Special” and the “Death Special” — armored trains with machine guns mounted on their roofs.

The miners need only disband, said Mother Jones. Lay down their arms.

When the miners ask, she will not turn over the telegram.

She fears blood, certainly. This ragtag army, 5,000 strong, is no match for the might of federal infantry columns backed by artillery and air support. She fears the creeks will run red from the mountain. She knows.

When she will not turn over the telegram, she is denounced. Mother Jones is a fake. A charlatan. Mother Jones, who once warned the governor that if he did not rid the state of these goddamned Baldwin-Felts mine guard thugs, there would be one hell of a bloodletting in these hills. Mother Jones, black-clad like Grandmother Death, has lost her nerve.

So they say.

These men, who fought for their country in the trenches and killing fields of the Great War, where their chances of survival, incredibly, were higher than in the sunless dark of the mines, where collapse and explosion and black lung lurked. These men, they no longer heed their mother. They march past her, into the hills.

Typically clad in a black dress, her face framed by a lace collar and black hat, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones fought fearlessly for workers’ rights. When she was tried for ignoring an injunction that prevented the striking miners from holding meetings, the prosecuting attorney, Reese Blizzard, called her "the most dangerous woman in America."

Johnny steps from beneath the mottled shadow of the elm, into the bright light of noon. The marchers are coming down the long field of the park, with their white robes and hoods. Some carry riot shields cut from oil drums or trash barrels, emblazoned with heraldic black eagles or swastikas or blood-drop crosses — the Mystical Insignia of a Klansman, whose red drop of blood symbolizes the blood that Christ shed for the Aryan race, so they believe. They are slapping batons and nightsticks against their shields, a dread tattoo.

Johnny stands before them in the field. This is his side of the park to hold. His people are behind him, still gathered beneath the monument. The police are just arriving in their riot gear, filing along the edge of the park. They will engage when the first blow is struck.

Too late.

The marchers grow closer, closer, churning across the field. A skirmish line. Johnny can feel the crash of their boots in the ground. Soon they will be upon him. A flood of shields and fists and mouths.

Johnny watches them come.

He is a white boy from the country. A veteran of the Third Infantry Division, with a truck bed full of papery skulls and skeletons, built to glow on the pedestals of an art gallery. He is a man who loves men. A redneck. He is an outlaw, which America has always loved more than a man in a white hat.

Still they come.

That cousin or coworker or boy from school. That grandfather.

They are fear and pride, weaponized.

They are hate.

Men so close to him. So far.

Behind him, the counter-protesters have found their hymn. A hum rises from their throats, soon to become words. Before him, the marchers have raised their weapons, white-knuckled, as if to strike. Johnny could, with a touch of his finger, drop their clubs.

He could start a war.

Johnny lowers his rifle and sets the weapon upright at his side, harmless, like a heeled dog. He raises his chin and closes his eyes, offering up the blood-red sash of his throat. His heart swells in his chest, unguarded. He turns his palms to the sky, waiting for the first fist or club or boot. The first strike, which will bring the police in time.

The marchers do not seem to see him. They march white-robed around his outstretched arms, blind to his sacrifice. As if he were only a monument. A man set in stone. These men, who believe they are knights. They rise again and again, as from the grave of history, bearing crosses on their chests. As if Christ himself, draped bloody before them, would not roar with shame.

Taylor Brown is the author of a short-story collection, “In the Season of Blood and Gold” (Press 53, 2014), as well as three novels from St. Martin's Press: “Fallen Land” (2016), “The River of Kings” (2017), and the forthcoming “Gods of Howl Mountain” (March 20, 2018). You can find his work in The Rumpus, Garden & Gun, the North Carolina Literary Review, and many other publications. He is a recipient of the Montana Prize in Fiction, a Southern Book Prize finalist, and the founder and editor-in-chief of BikeBound.com. A native of the Georgia coast, he now lives in Wilmington, North Carolina. Header photo courtesy of the Library of Congress