On Florida's sunshiny West Coast, John’s Pass Village and Boardwalk is a mecca of beachside business. Tourists abandon the beaches in droves, famished and reddened, and head for the boardwalk in search of their next meal of fried shrimp and hushpuppies. The boardwalk is packed with marina-front businesses selling overpriced ice cream and airbrushed T-shirts. Here, tourists board boats offering dolphin sightings and beer, and families wait hours to hover over a coveted table in one of the many seafood joints that offer the day’s fresh catch.

To the outside eye, St. Pete Beach and the neighboring barrier island beaches are a vacationer’s haven. The sand is white, the water is blue, and the surf is steady and strong.

But among the tourists and the snowbirds walk relics of St. Pete Beach’s nefarious past — a time when the beaches were hubs for a different kind of business altogether. It wasn’t just the green of dollar bills, after all, that bought every plank comprising the bustling boardwalk. Years ago, when mangroves grew dense where condos now tower over franchised surf shops, boys no older than 25 were catching big waves and fishing for what the locals call “square grouper” — a fisherman’s euphemism for bales of weed. Forty years ago, the boys of St. Pete Beach smuggled more marijuana than the nation had ever seen.

Thrill-seeking teenagers became millionaires overnight and grew sophisticated, international smuggling operations. They defied fear and death, smirked in the face of the law, and evaded punishment like a wet toadfish in a novice fisherman’s hands. They made more money in a week than most see in a lifetime.

But even outlaws have to grow old. And today, the same boys who grew up on the beach, raising hell and breaking rules, still call the place home. Here, they live with their ghosts, get high on memories and search for purpose in the long twilight of a life spent at sea. For to live as a pirate is to die as a pirate — and whether he submits willingly to nature’s course or clings desperately to the helm, each one eventually succumbs to the tide.

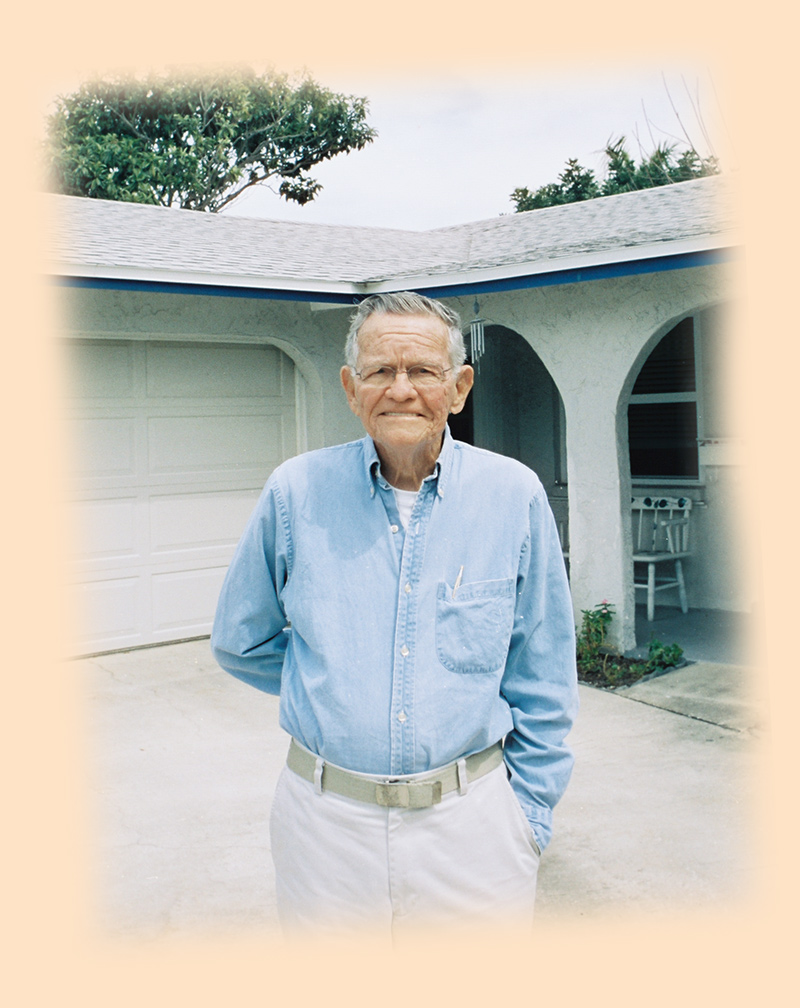

Steve Lamb

Steve Lamb, now 62 years old, still has an undeniable boyishness. He’s quick to grin, and his blue eyes sparkle with mischief. He’s trim and tanned, and even though he’s had both knees replaced, he remains a committed surfer. His thoughts jump quickly from one subject to another (and he struggles to remember names shortly after learning them), but he can still deliver a good joke (though it usually gets repeated). He’s charming and witty, even when it’s difficult to follow his frayed train of thought, as he casually recalls high crimes and good times. It’s not hard to imagine that though he might never have been the brains of an operation, he could certainly have been … well ... the balls.

And more than 40 years ago, Steve Lamb was one of a group of seven men (all save one younger than 25) who came to be known as the Steinhatchee Seven. They were busted smuggling more weed than had ever been found stateside. Most of the men had smuggled square grouper before; several of them had worked together for years, after growing up side-by-side on St. Pete Beach.

This was to be their biggest job yet — made dangerous by the volume of weed they intended to bring in and one ill-considered detail.

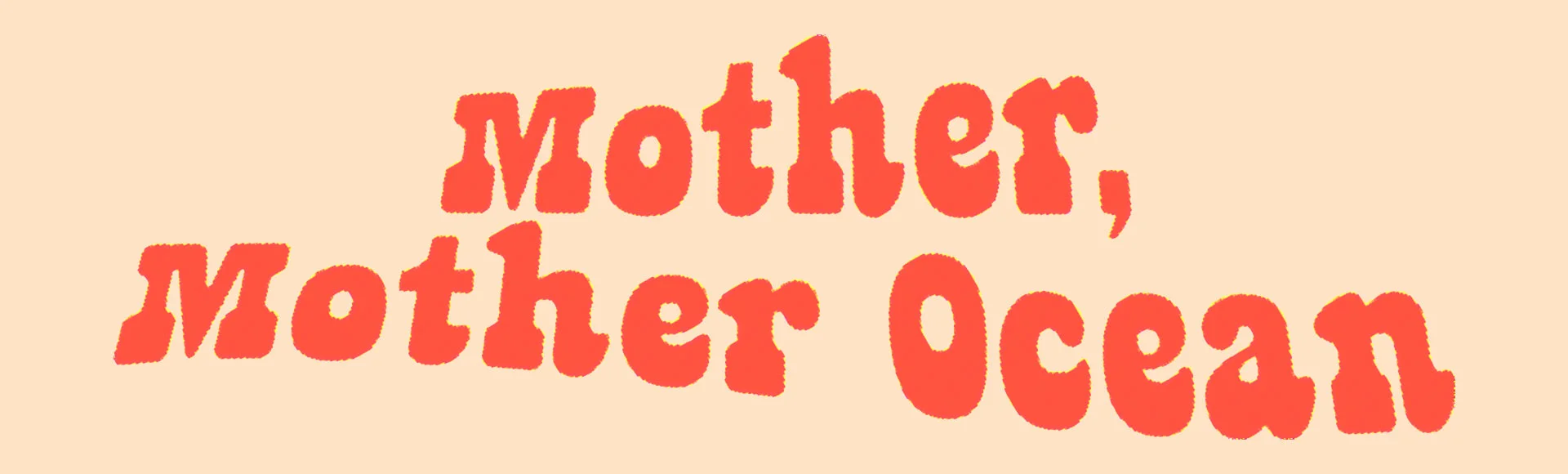

In the days leading up to March 5, 1973, the seven men had already moved 15 tons of marijuana from the lush jungles of Jamaica back to the swampy shores of West Florida. On this trip, they’d accounted for everything — they paid their supplier, a wealthy Jamaican man named Boobs; they brought gifts to the Jamaican community; they secured a shrimp boat to load to the brim with bales of weed. Just off of CR 361, known to locals as the Road to Nowhere, a notorious Dixie County road stretching from the rural town into the desolate marshes, 18-wheelers waited to pick up the pot upon drop-off. Buyers waited with bated breath and millions in cash. But what the smugglers failed to consider was the tide.

The shrimp boat arrived some 15 miles off of the Steinhatchee shore, just west of where Rocky Creek meets the ocean. Lamb, the youngest of the group at a mere 20 years old, went out to unload the shrimp boat’s illicit cargo onto a small fisherman’s scow. They unloaded from shrimper to scow and smaller boats repeatedly, working hastily in the cover of night.

But that much ganja is cumbersome, and as they moved their treasure ashore, the fickle tide retreated. They had stacked Lamb’s small boat with bales so high they rose above the salt flat’s horizon. Off the shore of sleepy Steinhatchee, the scow became more and more entrenched as the tide receded. Eventually, Lamb was hauling bales of weed on his back, and his boots sunk deep in the mud, ripped off, his bare feet falling victim to the sharp ridges of oyster beds below less and less saltwater. He persisted for hours. And though his efforts were tiresome, his reward would be great. Steve Lamb was going to be a millionaire.

As the tide inched away, the sun was creeping upward: The smugglers’ task was impossible. The men were not going to unload the entirety of their cargo before daylight.

The next day, Floyd “Bubba” Capo, who owned the shrimp boat and brought the crew to his home in Steinhatchee, paid his neighbors $25,000 to keep quiet about the mountain of marijuana sitting atop his boat. But hours later, the men found themselves besieged by cops and blinded by lights flashing red and blue.

The rural fishing community seemed an unlikely place for what was the largest drug bust the nation had yet seen. Frenzied media across the country dubbed the group of fishermen and boyhood friends the “Steinhatchee Seven.” The world was stunned when the nine tons of marijuana were seized. What they didn’t know was that another six tons had already been safely distributed near Clearwater.

Although much of the nation reeled in shock at the idea of such a mass of pot making its way stateside, beneath everyone’s noses, shrimp boats loaded with equivalent and larger loads traversed the open seas and waited offshore to deliver their coveted freight.

Initially, the seven men were sentenced to 20 years, but their sentences were ultimately reduced to less than two.

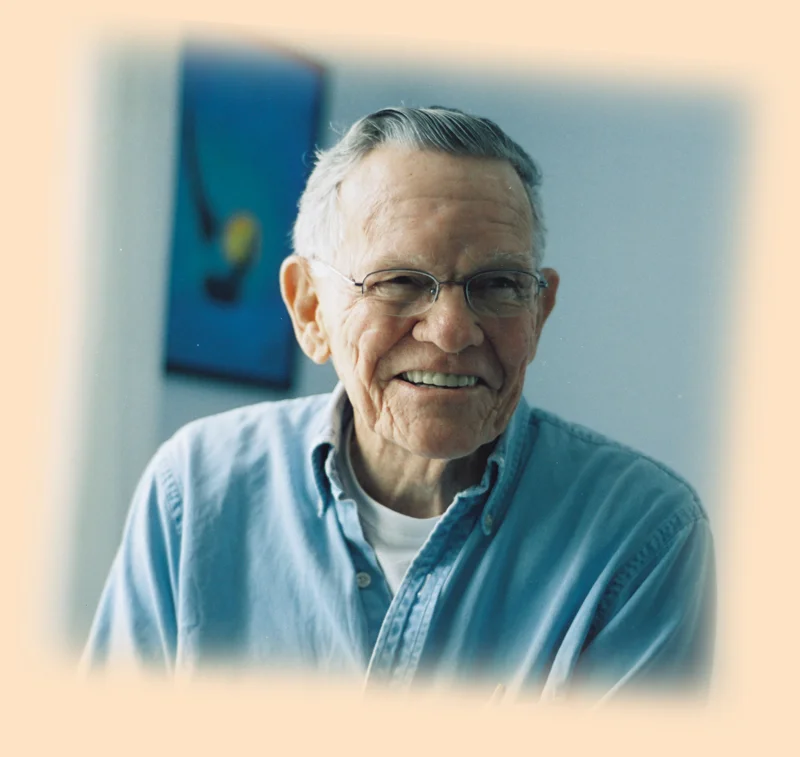

Tommy Powell

St. Pete Beach was a smuggler’s paradise — a playground of dense Old Florida wilderness. Mangroves smothered the barrier islands that dot the Gulf’s approach to the shore. Inlets whipped through the edges of landmasses, like dark alleyways to devious places. The overgrowth provided optimal cover for bringing in unlawful loads of precious green buds; the passageways offered speedy escape from anyone who meant to stop them.

“It was just cat-and-mouse, really, and if you were a mouse out in this stuff, you had a good chance of getting away,” says Lamb with a shrug. “If you don't know the swamps back there, you're gonna be pickin' your butt, stuck in the mud.”

Tommy Powell, a childhood friend of Lamb and several other members of the Seven, made his own place in the smuggling business, aside from other things, from knowing the swamps. He’d find unloading spots to sell to fellow smugglers.

“That was my favorite job in life, looking for unloading spots,” he says. “Instantly, an unloading spot was worth a million dollars, no matter what. If you used it, you were gonna make a lot more.”

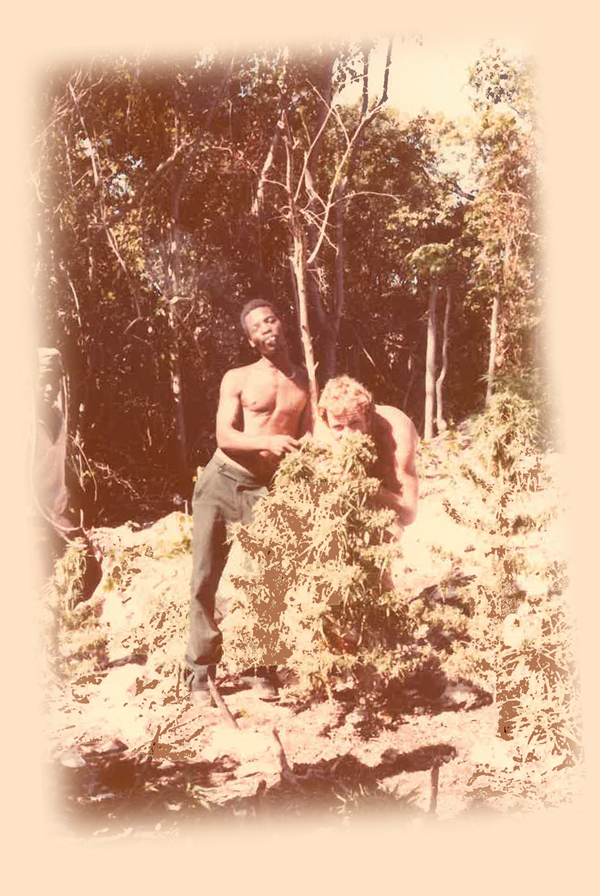

If you pass Tommy Powell on the streets today, you might not think much of him. His salt-and-pepper hair is just long enough to tuck behind his ears; he wears button-up, plaid shirts with flip-flops and wire-frame glasses. At first, he’s pensive and reserved, subtly testing your intentions and openly questioning your “scruples.” When he deems your company worthy, he’s jolly and gracious, even if still somewhat combative — but above all, he’s relentlessly aware and savvy.

In his lifetime, he’s brought hundreds of thousands of pounds of marijuana into the United States. He’s served prison sentences and sued the government, and been a refugee in countries throughout the world. And he, too, started as a St. Pete Beach boy.

It wasn’t as if the boys didn’t earn their dominion over of the land — they’d grown up entrenched in it, surfing, hunting and fishing. Lamb would catch and sell raccoons to people to eat, and he’d catch and sell sharks to Sea World for big money.

“We used to get crazy out here,” he says of what’s now Fort De Soto State Park. “We’d come out here and there'd be nobody. ... You could do crazy stuff. Now, you can't even go off of the sidewalk around here; if you get out of the car, you gotta pay $5.”

Lamb showed early signs of indifference for authority. It’s widely remembered that he nearly blew up the bridge that connects the beach to the mainland. Using stolen dynamite, he was fishing in bulk.

Maritime marijuana smuggling of the ’70s and ’80s was a complicated enterprise.

Smuggling meant getting a shrimp boat from the Florida coast to Jamaica or South America, where suppliers growing the bud in bulk would have it packaged and ready to be stowed aboard the big vessel. They’d then manage the fickle sea, returning home with cargo valued at several million dollars. “Go-fast” boats would jet out to the shrimp boats hovering 15 to 20 miles offshore, and take back to land as many bales as the small, speedy crafts could handle. Here, crews were waiting with semi-trucks or stripped-down Winnebagos, to stash the pot out of sight and get it into the hands of distributors. There were many sets of hands involved, and there was significant room for error.

“At the unloading spot, you don't get any higher than that. That's Stress City, times 1,000 or something,” Powell says. “The unloading spots are like the ultimate. It's not a high or anything — it's a combination of every feeling you have, because you know something’s gonna happen.”

Powell staked out drop-off spots from his souped-up motorhome, tricked out with $120,000 in electronics, which he’d use to tap into the local cops’ radio conversations.

“I could go onto a potential unloading spot and sit there for two weeks, just sit around and drink beer, smoke pot, listen to the radios and see what's going on. … You knew where everything was because you'd hear the cops talking to each other. You knew where they were going for coffee and stuff like that.”

Steve lamb on the beach

Tommy powell, back in the day

If a smuggler was on the verge of being busted, it wasn’t at all uncommon simply to sink the load. There are many accounts of bales of pot simply floating out to sea, precious cargo that just wasn’t quite as valuable as a smuggler’s freedom — the chance to sail and smuggle another day.

The trips certainly didn’t always go as planned, and sometimes it was precisely the pot that was to blame. But to smugglers in a time when weed was coming in by the tons and high crime was pretty damned easy to get away with, one lost load and a few million dollars gone was hardly enough to phase them. It was never about the money, anyway.

“I would just do it for the thrill,” Lamb says. “It was for the excitement, because there wasn't anybody getting busted. You'd just be like, ‘Hey, come get me! Bye!’’

“I never was in my business to make money, dude,” says Powell. “I made so much fucking money, and I never wanted to make money. I was in it for the reefer, no doubt about it. I had fun; I had my Lear jet; I had a Bell JetRanger; I had houses all over the world. … I was doing it to get everybody high.”

Both Powell and Lamb speak flippantly of money — how little they cared for it, how they had so much cash, at times, that it was hard to keep rats from eating it.

The money came in bulky packs of bills, stacked neatly within briefcases — the stuff you see in movie scenes. That’s how Steve Lamb knows $1 million in twenties weighs 110 pounds.

When you’re young and dumb and inflated by your own sense of invincibility, It’s hard to contain the joy that comes from having more money than time to spend it. But lack of discretion can get a boy into trouble.

Millions were buried on islands and in backyards, under the careful watch of relatives who sometimes took a little for themselves. Lamb was known to run his mouth about the money that was coming in, and on more than one occasion, someone got to it before he could. Someone once dug up Lamb’s money and was so kind as to leave a beer can in its stead, and an empty one at that.

Powell also lost nearly $400,000 when a landowner dug up the suitcase it was buried in. That lucky sucker got to keep the cash.

But that kind of money, in such bulk that it must be buried or stowed, draws keen interest in a small community — and this was happening up and down Florida’s coast. It may be hard to imagine now, but Old Florida was a special breed of wild, both in terrain and in population.

As maritime marijuana smuggling reached an all-time high, law enforcement kicked into high gear, and they were looking closely at Florida’s untamed coastline. The Drug Enforcement Agency formed just after the Steinhatchee Seven were busted. And as the issue escalated, one man was being prepared for a career he never expected.

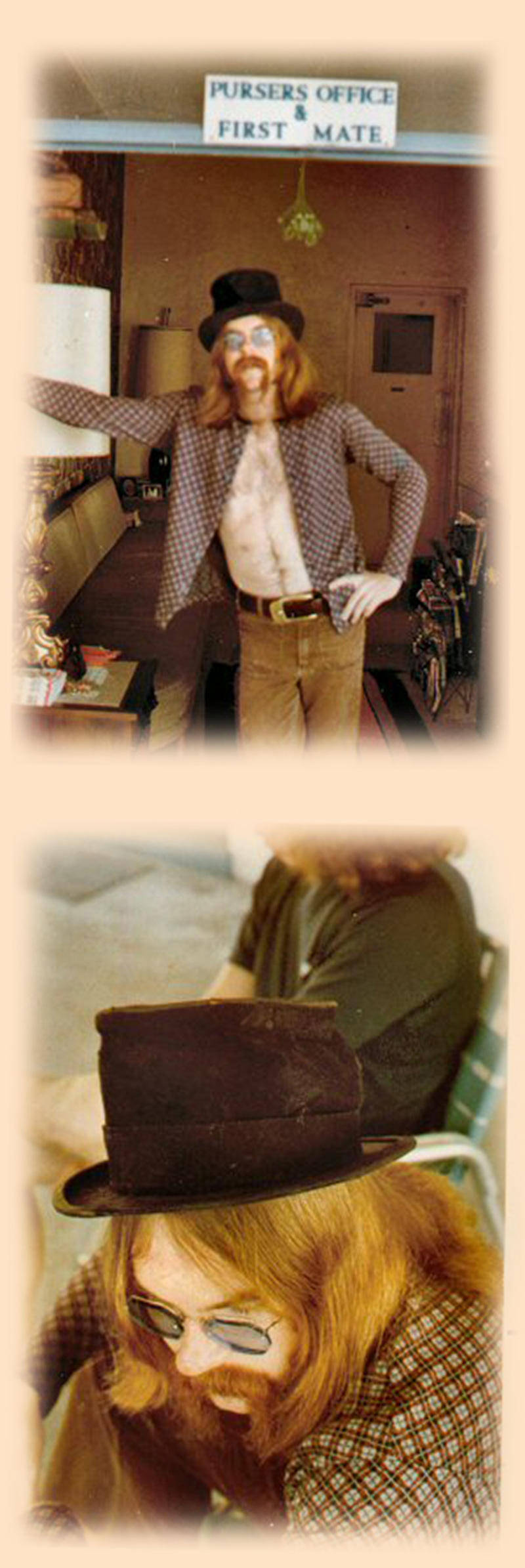

Like Steve Lamb and four of the six other members of the Steinhatchee Seven, Charlie Fuss had been born and raised on Florida beaches, though he was from just down the road in Tampa.

“I grew up in little sailboats when I was a little kid,” says Fuss. “So, I've always loved boats and the sea and I've always had feelings for people who are sailors or fishermen.”

Fuss was a high school dropout who made his life at sea. After his sophomore year, he left school for a job washing dishes on a Victory ship. He joined the Navy and did two deployments in Korea. Unlike the drug-ridden jungles of Vietnam, sailors’ desperation in Korea pushed them, at worst, to break into first-aid kits and steal morphine and to put Aqua Velva after-shave into their coffee to cope with temperatures that reached 20 degrees below zero.

After Korea, Fuss used the G.I. Bill to get his G.E.D., and then two degrees in biology. In college, he met the love of his life, Carol Ann, a Louisiana girl who’d grown up on a sugar plantation. He was working on his thesis in New Orleans, and he needed someone to type it for him. Carol Ann was his girl then, as she is now.

He became a U.S. Fisheries Agent, and over the years, his roles were varied. He partook in research throughout the gulf, off of Louisiana’s murky shores. He moved to Florida, where he enforced the Marine Mammal Protection Act up and down the coast, finding and apprehending poachers capturing some of the sea’s most miraculous creatures. He worked with the Coast Guard, flying planes to keep track of foreign vessels — especially those from Cuba and Russia, as the Cold War hovered over the country like an impending freeze.

With one call in 1983, everything changed.

“One day, I got a call from a Washington office,” recounts Fuss, with the kind of practiced delivery that reveals he’s told this story before, “and he said, ‘Hey, Charlie, how'd ya like to work for the vice president?’ I didn't know who they were; I thought they were pulling my leg. I said, ‘Vice president of what?’”

Charlie Fuss

Fuss shakes hands with his boss, vice president George H.W. Bush

Vice President George H. W. Bush was bringing the War on Drugs into focus. Thanks to the boys of the Steinhatchee Seven, the nation had long since known that marijuana was seeping into the nation’s swampy portals by boat. The National Narcotics Interdiction board needed someone who knew a thing or two about fishermen, ships and fishing operations to put an end to all the pot making its way stateside. And above all things, Charlie Fuss was a fisherman’s fisherman, whose moral compass always pointed due North.

“It seemed the patriotic thing to do,” he says.

Like many federal political appointments, the expectation was that Charlie would pack up his family, now a wife and six kids, and move on up to D.C.

“I said, ‘If you make me move up here, you’re going to have to put me on food stamps, because I’ve got six kids, and I just can't afford it,’” Fuss says.

He could hear Bush’s chief of staff, a formidable Naval Admiral named Daniel J. Murphy, yelling at his assistant who’d offered Fuss the job.

“I could hear him yelling at the guy, and he says, ‘What the hell did you give this guy the job for? He says he’ll take the job but he won't move!’”

But such were Charlie Fuss’s priorities — he wouldn’t separate from his family; he wouldn’t leave behind the sea. They found office space for him in the Coast Guard station, and Fuss set out to bring maritime drug smuggling to a screeching halt.

By the time Fuss had been called to duty (and after close encounters with law enforcement), Lamb and Powell had both fled the country.

Lamb was living in Venezuela. He’d made connections there as a smuggler, and the people of his temporary home shielded him from threats of extradition. He was in Venezuela on and off for 12 years, which took a serious toll on the life he’d built stateside.

Still, he managed to conduct some business while abroad, shipping three to 500 pounds of weed by mail to the states via UPS and FedEx. He even snuck back into the country to attend his mother’s funeral.

Meanwhile, Powell made his way to Colombia. There, he fell in love with a Swedish woman who later brought him to her home country. Before traveling to Europe, he took his trailer up to Boston to make a visit to Harvard’s Law Library. He brought with him a fake ID, claiming to be a visiting professor from the University of Florida. He studied the extradition treaties of the time between the U.S. and Sweden. He determined that in Sweden, he couldn’t be extradited for conspiracy to distribute marijuana, because of laws of reciprocity.

“They have to have the same exact crime that we've got, but they don’t have conspiracy [to distribute] in Sweden. So I’m going, ‘Geez, that’s cool. Five years, no problem. I'm out of here.”

With confidence in his understanding of the law, Powell began a happy life in Sweden. He and his wife soon had a son. A few years later, they had another. But on the day his second son was born, Powell was taken into police custody, thus beginning a long history of contending with the law.

When confronted by the vice consul of the American Embassy in the Swedish prison, he denied most of his indictment — claiming it was a case of mistaken identity. Surely, he said, they were after his brother Jimmy instead. The vice consul persisted, telling Powell he was due for life without parole plus 70 years. He also said the authorities would prevent Powell’s wife and kids from ever entering the states.

“What do you think I did?” Powell says. “I jumped across the table, grabbed his throat and fucking strangled him as hard as I fucking could. That's the way it was, man. I mean, I was an ass-kicker. I don’t take shit from anybody. Nowadays, I'm like, ‘Was that really me?’”

Today, although Powell still conducts himself with the utmost sentience and self-assurance, he’s something of a pacifist. He recalls his former self, gently brushing back shaggy grey hair from his eyes and sprawling back onto a couch lined with colorful throw pillows you’d imagine on the couches of the Taj Mahal. He lives in his girlfriend’s house on St. Pete Beach and works in computer forensics, a skill he taught himself with the same tenacity he learned his Constitutional rights. While in prison, Powell found himself placed repeatedly at work in the libraries. Here he learned all that he could about the law — beginning and ending with the freedoms that our Founding Fathers assured us. And with that knowledge, he took to the courts.

“I sued the government probably 20 times,” he says, proudly. He even represented himself in the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington.

But while Powell and Lamb were spending years in exile and prison, Charlie Fuss was working diligently to put an end to their way of life.

There was nothing vindictive or self-righteous about the way Charlie Fuss conducted business as a member of the National Narcotics Border Interdiction System staff (and later the Office of National Drug Control Policy). For him, it was a duty to which he was called. And as a member of the St. Pete Beach community and a man who’d grown up with a deep love and respect for the sea, his efforts were rooted in empathy.

Much of what we know about smugglers today, we know thanks to Charlie Fuss. He changed the entire practice of drug-trafficking interdiction and control by doing something that came quite naturally to him: talking to the fishermen.

“I said, ‘Well, what the hell? The most direct way is to ask them, you know?’ They’re in jail, and most of them were faced with mandatory minimum sentences … before that they did three years or 24 months. Now they’re going to jail for 10 years and 20 years, and so they’re really willing to help.’”

Whether they had fallen subject to their own greed or someone else’s malice, Fuss found himself able to understand where the fishermen were coming from.

“I felt sorry for ’em,” he says. “In my days of exploratory fishing, I had worked at sea on nasty nights aboard shrimp trawlers, and I knew what kind of hard work it was. So I had empathy for ’em. And it was pretty sad to see whole groups of commercial fishermen that would have normally been hardworking, productive citizens go down the drain and receive extensive prison sentences.”

This kind of rhetoric, sincere and true, enabled Charlie Fuss to get the fishermen talking. He’d visit prisons throughout the Southeast, talking to men looking at life behind bars, and he’d remind them of the freedom they were sacrificing while the men who put them up to the task ran free. And as he built his rapport, the men not only started talking, but they started asking for Fuss. At the Federal Correctional Complex in Butner, North Carolina, they even called him “Uncle Charlie.” He’d help them get shorter sentences in return for names of the men running the show. And he’d start by telling sea stories.

Fuss was never intimidated by the smugglers he encountered — most of them were just breezy surfer boys or blue-collar fishermen. And even the ones who were known to be dangerous didn’t scare him: Nothing could compare to knowing the power of the sea. He’d had more than one brush with death aboard tiny research ships tossed by the unmerciful ocean.

“Being afraid of drug smugglers was nothing compared to that, because they were just human beings,” Fuss says.

Through Charlie’s work, more than 100 smugglers were convicted. He also developed intelligence that was pivotal to breaking down the maritime marijuana smuggling operation at large. By 1987, the big drug busts were becoming so frequent that kingpins of the operations simply couldn’t justify the risk. Maritime marijuana smuggling had taken its last gasps of salty air.

And maybe it was simply the hubris of it all that finally brought smugglers to their knees — overextending their operations and heading into unfamiliar waters.

“They had huge egos, because the early guys got away with it,” Fuss says. “And they had so much money the rats were eating it, so they just believed they were unstoppable.”

But maybe that’s just what being a young man is all about.

No matter how righteous men like Charlie Fuss worked to keep the generation beneath them out of harm’s way, there were casualties of their carefree lifestyle. And loss is something smugglers, if not all young men, become well acquainted with. But if nothing else, a smuggler’s sendoff is a sight to behold.

Powell’s Colombian best friend was a widely feared hitman of sorts named Rafael. He was shot dead by one of his primos, while lying in his hammock. At Rafael's funeral, Powell hovered in the back, his waist long hair flowing in the breeze, in his definitively Floridian casual attire — a t-shirt, jeans and tennis shoes. He waited for just the right moment. And when the moment struck, just as the priest completed the service, “Que eres polvo y al polvo volverás,” Tommy reached down to the boombox he’d carried to the ceremony. He pressed play, and over the hills, ringing upward toward his friend’s fallen spirit, he played Kansas’s ubiquitous hit, “Dust in the Wind.” The whole congregation turned and looked but said nothing. They knew who Powell was, and they knew what he meant.

But not all deaths gave clean-cut cause for impassioned funeral proceedings. Some left questions that linger to this day.

Mike Knight, the leader of the Steinhatchee Seven, the one who stewarded many into the smuggling game, died under mysterious circumstances in the summer of 1978. His body was found floating in the water off of Indian Rocks Beach, after a night he’d spent enjoying the moonlit ocean with his girlfriend, Rose Skillen. In reports, she recounted Knight slipping into the water and then experiencing intense seizures and spasms that ultimately caused him to drown. She claimed to have tried to save him.

Other theories exist. Prior to his death, both Knight and Lamb had become the target of an envious man named Gene Coats. Coats robbed Lamb and another smuggler at gunpoint, and Lamb found an unexploded bomb in his car that was also the work of Coats. Knight was under similar threats.

Powell began to worry seriously for his friend Mike Knight. And he tried to save him.

He found Knight in a hotel room with Lamb, which he refused to leave. “He was in there with Steve Lamb; they were both doing heroin, and I knew they saw the writing on the wall, and he would only talk to me through the bathroom window.”

He begged his friend to let him take control of the situation, but Knight refused. A month later, his lifeless body was floating in the ocean.

“He drowned,” Powell says, “but he was the best swimmer in the world. I'd be with him swimming, and he'd be taking acid and Quaaludes and whatever, and he'd be high as a dog and he couldn't — there's no way he would drown. He never drowned, and that's the suspicious part.”

Lamb, at most, thinks it was an overdose prompted by the stress of the times, but even he retains some reservations about the circumstance of it.

“He swam like a fish and they found him floating in the canal. I think he just got jacked up on some cocaine, because that was the time when they were trying to rob us,” he says.

Charlie Fuss retains a practical viewpoint on the theories surrounding Knight’s death. “Those conspiracy theories get going just because those guys are what they are,” he says, “and I have a strong feeling that Mike Knight was just taking some stuff for some reason, and he went out and fell in the water and drowned. I don’t think anybody held his head under but Steve probably has a different view of that. But Steve wants to make a conspiracy if he can, because that’s what sells books.”

When a smuggler is put out of business, or a government official is forced to retire, what’s a man to do? In the case of these St. Pete Beach boys, the answer is: tell your story.

Steve Lamb published a book in 2009 entitled “The Smuggler's Ghost: When Marijuana Turned a Florida Teen Into a Millionaire Fugitive.” It took him five years to publish with the help of writer Diane Marcou. It’s a major source of pride for Lamb, who spends most of his days now promoting the work, which can be found in many small shops around the island and a claim to fame he wears, quite literally, on his sleeve. There was talk of the book being made into a movie, but fittingly, the potential producer got caught up in his own scandal of drugs, money and mischief.

Charlie Fuss wrote an intro to Lamb’s book. He agreed to do so only after reading the transcript and seeing to it that it held pretty true to life.

“I said, ‘You’re nuts, I was on the other side! I'm not going to write anything good about your book,’” Fuss says. “I started reading it, and I said, damn, this is pretty good, and it's pretty true to life from what I remember back in those days. So I eventually said, ‘OK, I'll write a note,’ but I didn’t think it was going to go in the front of the book.”

Fuss had his own book to consider. He published “Sea of Grass: The Maritime Drug War, 1970-1990” in 1996. Like Lamb, it took him five years to write, and he gives Carol Ann due credit for coming to his aid as a typist yet again. The book chronicles marijuana coming into the country by sea and his own efforts to stop it. It’s on file in many colleges throughout the nation, and the admiral of the Coast Guard even put it on his reading list. The book provides an unparalleled insight into the drug war of his time.

But it’s hard for Fuss not to feel a little bitter toward the small-town fame Lamb has gained from his book. “It pisses me off every once in awhile when I see him, and the fact that those books are selling like hotcakes,” he says.

Meanwhile, Powell returned to college and enrolled in writing courses. His teenage classmates were wowed by the tales he’d workshop — stories of smuggling pot on the high seas. They’d catch him after class, smoking cigarettes, and ask if he really did all that he said. They’d want desperately to know if he’d killed anyone, but they’ll have to read his book to find out. Powell has also been working on a chronicle of his own — he’s got 80,000 words thus far.

Between the three men and the legends that circulate the island still today, somewhere lies the truth, buried deep in the sand, deteriorating and fading with time, like so many wads of hidden cash fortunes.

Charlie Fuss put to death a way of life for Lamb and Powell and the other young men who craved a life of sea and scandal. The drug routes moved to Mexico, where mules crossed the border in many forms, and the war on drugs entered a new, increasingly violent chapter. Long gone now are the days where surfers looking for a big thrill took to the high sea in search of pot, women and millions. They were replaced by criminals with automatic weapons, kicking bales of cocaine out of helicopters and into the ocean.

If there’s one thing that marijuana smugglers and Charlie Fuss agree on, it’s that “fucking cocaine is the bane of man's existence,” says Powell.

But for Powell and Lamb, marijuana is simply an herb, a gift from God to help cope with the trials and tribulations he places in our path.

“Read the first page of the Bible,” says Lamb, “Genesis 1:11-12, ‘God gave all seed bearing herbs and weeds for mankind, and he saw that it was good.’ And so did I.”

Powell just wants the world to see it his way — that “reefer,” as he expressly calls it, was never bad to begin with. It’s a double-edged sword to see marijuana legalized now. On the one hand, he counts it as a feat he helped accomplish; on the other, he feels he hasn’t gotten the credit that’s due.

“I feel like I did my share, but I kind of got a little left out. … I probably brought in 300,000 pounds of reefer, and you know me and my partners — I figured out it's like about 3 million pounds, and it helped probably to get marijuana legalized in the United States.”

Of course, the legalization of marijuana is painful for a man whose career revolved around trying to stop the drug from entering his hometown, to keep it out of the country he fought for in more ways than one.

“I read the newspapers, and I have indigestion,” Fuss says. “And that's just the way I am; I don’t know if my kids would agree with me or not.”

STEVE LAMB (SECOND FROM LEFT, BACK ROW) PARTIES WITH FRIENDS, INCLUDING (BACK ROW AT LEFT) JIMMY BUFFETT

Today, the St. Pete beachfront is lined with a wall of resorts. Modest homes that once overlooked a deep, white shore are now blocked by towering stucco condos in sun-worn shades of peach, yellow, pink, green and blue. Where there were jungles of mangroves and smugglers on the run, there are dense forests of blue umbrellas and families with small children building castles in the sand.

A lot has changed since they all were young men, surfing the St. Pete waves and chasing quick fortunes and cheap thrills — it’s changed since Charlie Fuss shook the vice president’s hand and took on a course of duty that he never foresaw.

None of the three have significant fortunes to their names, but money never did anything to define them.

“I made a lot of money doing reefer, and I lost it all doing reefer,” Powell says. “Ya know, and I’m not sad about that. Actually, I kind of like being broke, because I don’t have any bullshit friends or people that are trying to stick their nose up my ass or whatever so it’s kind of cool. I’m happy.”

And for whatever recognition may have passed over Powell, locals still pay homage. He frequently finds blunts and buds tucked in his mailbox or dropped on his porch — anonymous tariffs paid by those who know what he did for their access to the stuff.

Charlie Fuss still lives in the home where he raised his six children; it’s an embodiment of his patriotic spirit and his nautical affectations. Every corner is white and blue, with accents of red adorned tastefully throughout. The walls are covered with framed maps and pictures of ships, certificates and letters of thanks from politicians and commanders. He still hears from some of the fishermen whose freedom he negotiated, and that makes him proud.

But more prominent than his love for country and sea is his profound love for his family, his wife of 56 years, and their beautiful children and grandchildren. They are his legacy and his purpose.

Nowadays, Steve Lamb is a man unbridled by regret. At the age of 62, his life in retrospect is rife with blessings. He wears a windbreaker adorned by pirate ships. Beneath his favorite jacket is a yellow T-shirt with “The Smuggler’s Ghost” emblazoned on the front in blue print, with an illustration of men unloading bales of marijuana from a shrimp boat onto a go-fast boat. On the go-fast boat is a briefcase, which you can infer is filled with stacks of cash. “I wouldn't take the money out there,” he corrects. “You get busted, and you lost the money and the weed.”

Even now Steve Lamb has a kind of contagious positivity gained from living many lives in one.

“The book I’m writing right now is gonna be ‘The Smuggler's Holy Ghost,’ because there would be at least 100 times I should have been dead from the cartel, dead on the floor from drugs, from waves, car wrecks, people shooting guns, just all types of shit. It's a blessing. Trials and tribulations bring me closer to the good Lord. … My God’s a good God; he takes care of me.”

Ask Steve Lamb when he quit smuggling, and he’ll raise his thick white eyebrows from behind his Oakley sunglasses and say, “Tomorrow.”

While Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” plays from the stereo of Lamb’s black 1990s Plymouth Neon, which he repeatedly refers to as his “Mercedes-Benz,” he cracks a smile and says smuggling was the “best time of my life. I don’t regret anything. I'm happy; the good Lord blessed me. I’ve got nothin' to complain about; duddn't do any good, anyway. No, I just believe in giving thanks and being happy for all things, it's just a good way to go.”