Remembering Selma

As We Commemorate the Heroes of 50 Years Ago, We Also Come to Terms With a Still Uncertain Future

SELMA, Ala. — “Hey, y’all. Wake up.”

Over the past two decades, tossing those two sentences over my shoulder toward my slumbering children became part of a ritual when ferrying my family between Columbus, Ga. — my hometown and where we lived for a dozen years — to visit relatives in my wife’s hometown, Jackson, Miss.

A third of that trip, a 133-mile stretch between Montgomery and Cuba, Ala., was on state Highway 80. Beyond compulsory vigilance for speed traps along the way, rolling down what is now called Jefferson Davis Highway usually was an uneventful journey.

Until we approached the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

I didn’t stir my two sons and my daughter because the bridge’s namesake was a general in the Confederate Army and a former Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. I was just hoping they could understand, as I did, that this 1,248-foot-long span arching across the Alabama River was also an arch from a hateful past to a less hateful, but still racially tortured now.

As thousands like myself made the pilgrimage to Selma last weekend to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, we were here to reflect on where we are as a nation and where we’re headed.

As it did each time I drove over it, this steel and concrete structure gave me chills. The ease with which my family and I traverse it belies its horrific history and that of Selma, of Alabama, of the South.

Selma was like most of the South. White citizens regarded blacks not only as beneath them, but also as a threat to their way of life. It was a place where strident segregationists had no problem displaying their contempt for those who would challenge them.

That was also what made the city so attractive — 50 years ago — to Bernard LaFayette.

Today, Dr. Bernard LaFayette is the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s national board chairman and a distinguished scholar-in-residence at Atlanta’s Emory University. But in 1961, he was a 20-year-old undergraduate at Nashville's American Baptist Theological Seminary, determined to make changes and to challenge segregation. He was a staple of the Nashville sit-ins. He’d already staged a successful impromptu Freedom Ride with his close friend and fellow student activist John Lewis (now the U.S. congressman, in his 15th term, for Georgia’s 5th District). In 1959, while traveling to LaFayette's home in Tampa for Christmas break, they decided to exercise their rights as interstate passengers by sitting in the front of a bus — something that was prohibited in the South — from Nashville to Birmingham, where he and others on the Nashville Student Movement Ride were arrested.

The Freedom Rides were among a flurry of movements undertaken at that time. Those involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), those involved with the Freedom Riders and the young people who drove the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, all created movements that brought about change. LaFayette and others were trained in nonviolence and trained in how to lead movements that spanned long stretches of time — the Freedom Rides that lasted from May to November and the three months of sit-ins in Nashville.

Dr. Bernard Lafayette in Selma last weekend.

It was on one of those Freedom Rides in 1961 when Selma first landed on LaFayette’s radar, but not actually in his sight. After a violent confrontation at the Montgomery Greyhound station, they came up with another plan.

“Freedom Rides did not go through Selma, Ala.,” LaFayette told me, recalling his trip crossing Highway 80 from Montgomery to Jackson. “We needed a decoy bus. I was on the first bus. We heard there was about a mob of 2,000 people waiting on the bus. So we had a decoy bus that went around Selma, Ala. That was one of my first memories of Selma. I’d never heard of it before.”

After the Freedom Rides were done, James Bevel, Diane Nash, Lewis and LaFayette decided they were going to devote more time to the Civil Rights Movement. LaFayette headed for Atlanta to get an assignment to head a voter-registration campaign.

At that time, voter registration was considered a benign community-action activity. It had nowhere near the sizzle for the news media of the more radical protests. Blacks had the right to vote, but there was rampant discrimination in areas where there were large black populations. It was for that reason, LaFayette said, voter registration efforts bypassed urban areas, but instead concentrated on rural areas where there were large numbers of blacks who were not participating in government.

But when LaFayette got to Atlanta, James Foreman, executive secretary of SNCC, told LaFayette all the voter-registration assignments had been taken. Bob Moses had Mississippi and Charles Sherrod had Southwest Georgia. LaFayette was livid, he said, because Foreman had promised him an assignment. Foreman finally offered him an assistant director’s position.

“I said no,” LaFayette said. “I wanted to demonstrate the things that I had studied. We looked on a map on the wall and there was Selma with an X through it.”

SNCC had decided it wasn’t going to stage a voter-registration project in Selma — which meant all of Alabama — because the two SNCC teams sent there had returned with the same report. Nothing could be done in Selma, they said, because the black folks were too scared and the white folks were too mean.

“He asked me if I wanted to take a look at it,” LaFayette said. “I told him, no, I want to take it. I had to do some research to find out why it is, of all places, why Selma was like that. We always thought Mississippi (where LaFayette had been arrested in 1961 and sentenced to a month at the Parchman State Prison Farm) was like that. Even on the Freedom Rides, we thought that Mississippi was the place where we had to deal with all of that. What I had to do was do some research. Had to find me a library where I could learn about scared black folks and mean white folks.”

He learned about the power structure on the state and local levels. He studied Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, a strict segregationist, and tiny Selma, whose chapter of the White Citizen’s Council — a racist organization whose membership rolls were laden with upper- and middle-class people — actually met in the local bank’s boardroom.

“They (Selma officials) knew all the black folks,” LaFayette said. “They controlled the jobs and even the other white folks. They controlled them. You had eight families that controlled all of Dallas County. If you were a part of those families, you were a part of the power structure, and you never had to worry about a job.

“They would target those ministers to make sure they did not come out and try to what they called ‘step out of line,’” he said. “Here’s what they did to the other black folks: If somebody spoke out, or tried to come to any kind of rally, what they would do is … they would fire your mother-in-law from her job and tell her, ‘You need to spend more time with your son-in-law since he needs to learn how to behave.’ There would be implosion of the family. You would be in more trouble getting your mother-in-law fired from her job than you losing your job.”

What’s more, any political activity could cost you your life. In 1962, LaFayette became the director of SNCC’s Alabama Voter Registration Project and did so without incident until a year later, on Feb. 18, 1963.

LaFayette, after returning from a voter registration meeting, noticed a car parked in front of his home. One of the white men there asked LaFayette if he would give him a push to get his car started.

What they were doing, LaFayette surmised, was trying to lure him into the white neighborhood on the other side of town. He guessed there was a mob waiting on him there. The man looked at his car’s rear bumper and LaFayette’s front bumper, then told Lafayette he wasn’t sure they would align. He asked LaFayette to take a look.

“I’d told them I wasn’t going to charge them (for the push),’’ LaFayette said. “I realized then they were going to try to knock me out. That’s when they attacked me and knocked me to the pavement. I yelled to my neighbor when I found out one of the guys had a gun. That’s what they beat me with.

“I had a neighbor upstairs and yelled for him, ‘Red! Red!’ so somebody could see what was happening. I didn’t yell until I saw he had a gun. Red, a Vietnam vet, ran across the balcony with his gun. I stood between Red and the guy, because Red was going to shoot him. He was jockeying to get into position to get a good aim at him. I stood between them so he wouldn’t shoot him. It was from a moral point of view, but also from a practical point of view. If Red had shot that white man, both of us would have been in jail there for life.”

Red scared the men away, but not before LaFayette was severely beaten. He would spend a few days in the hospital and considered himself fortunate. Two weeks after the beating, an FBI team out of Mobile came to investigate. The investigation was necessary because the Justice Department had an injunction on those Alabama counties where blacks had been disproportionately represented in voter registration.

An FBI agent told LaFayette there had been a three-state conspiracy, in which “three of us were scheduled to be killed the same night about the same time,” LaFayette said. The three were LaFayette, Ben Elton Cox in Louisiana and Medgar Evers in Mississippi.

Cox wasn’t home, so his would-be killers couldn’t find him, but Evers was shot in his driveway in Jackson and died in a local hospital less than an hour later. LaFayette didn’t know Evers was dead until the next day because he was still hospitalized from his own beating.

The FBI told LaFayette the plan had been hatched in New Orleans. Who exactly hatched it remains a mystery. All LaFayette was told was that it was a “Klan-like group.”

“The Klan didn’t operate in Selma,” LaFayette said. “You never saw anybody with a robe on in Selma. You know why? Because every white male, 21 and over, was automatically a part of (Dallas County Sheriff) Jim Clark’s posse. You already had your gun and your horse. All you had to do was go get your badge.”

The backing of state officials gave them even more power. To facilitate the suppression of the state’s African-American citizens, Gov. Wallace placed a ban on nighttime demonstrations.

Wallace’s ban not only failed but also was fatal.

During a nighttime march on Feb. 18, 1965, demonstrator Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and killed in Marion, a town 30-odd miles northwest of Selma, by state trooper James Bonard Fowler (who was finally indicted for murder and pled guilty to manslaughter in 2010). The bullet may have killed Jackson, but it also gave life to an idea.

Two days after Jackson was gunned down, James Bevel and LaFayette went to visit the Jackson family for what initially was a grief counseling session. It was a particularly difficult tragedy because Jackson had been the sole breadwinner in his family. Bevel, especially disturbed by this killing, asked Jackson’s grandfather if the organizations should continue the marches.

“And he said, yes, by all means,” LaFayette said. “(Bevel) asked him would he be willing to lead the march, and he said, ‘Yeah. I got nothing else to lose. I’ve lost everything.’”

Lafayette said Bevel wanted this march to be proportionate to Jackson’s death. It was bigger than marching to the county courthouse to get registered and being denied. An Alabama state trooper had killed Jackson.

“James said, ‘I got a message I want to deliver to Gov. Wallace,’” LaFayette said. Bevel told LaFayette he wanted to walk all the way to Montgomery. “We were on the way to the mass (voter-registration) meeting, and he asked me, ‘If I walked to Montgomery, do you think anybody else would come with me?’ I told him, ‘I don’t know about anybody else, but I will go with you.’”

Thus was hatched the idea for the Selma-to-Montgomery marches.

Scenes from the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, March 7, 2015.

“He went before the meeting that night and asked would anybody else join him in marching to Montgomery,” LaFayette said. “I was in the pulpit behind him and everybody in the place stood up. He turned to me and said, ‘It looks like we got a march.’”

Which quite possibly saved the lives of white citizens in and around Selma. The fear that once gripped the black population had been overtaken by rage. The white power structure held the belief that the only reason the blacks stood up for themselves was at the urging of white “interlopers” encouraging them. They felt blacks around Selma would not dare stand up on their own. That was a near horrific miscalculation.

“When Jimmie Lee Jackson got killed, you could not buy a bullet or a gun within a 50- mile radius,” LaFayette told me. “The farmers out there — the black farmers — had bought up all the ammunition. Do you know what they told us? They said, ‘Y’all (protesters) can go sit down now. They’re speaking our language. We’ll take it from here.' They were arming themselves for a bloody situation.

“They could shoot the eyes out of a squirrel running,” LaFayette continues. “These guys used to hunt to eat. What we said was we had to escalate the nonviolent movement otherwise you are going to open the door right now for other folks (to be killed). Black folks, there were some of them that, especially in those rural areas, where they actually owned their own farms, they were not nonviolent. They said we support the movement, but they said we can’t be involved in no marches and stuff.”

So LaFayette said the group had to escalate and have a larger march. They decided the goal was to stage a five-day, 51-mile Selma-to-Montgomery march.

As it turned out there would be three marches, the first of which would be March 7, 1965. The second, which included Dr. Martin Luther King and became known as Turnaround Tuesday, was on March 9. Only the third, which began March 21, made it all the way to Montgomery.

It was at that first march where some 600 protesters who stood at the base of the Edmund Pettus Bridge were beaten by state and local law enforcement officials. The world looked on in horror. That included LaFayette, who was in Chicago recruiting and training people for the marches.

“I was going back and forth to Chicago recruiting folks to come down,” LaFayette said. “We had the Vice Lords, a gang, to come down as marshals. If you saw film of the Selma march, you’ll see a fella who had the beret on — turned backwards on his head — carrying the American flag. That was one of the leaders of the Vice Lords, Lamar McCoy, that I recruited. Selma was their (street gangs’) training ground in nonviolence.”

LaFayette returned to Alabama after Bloody Sunday to participate in the second and third marches. Their efforts to recruit, and the nation witnessing the brutality on Bloody Sunday, proved so successful that finding flights to Montgomery were a challenge. Eventually he found a flight into Birmingham where he and Diane Nash’s uncle would be picked up and driven to Selma.

When LaFayette reached the Birmingham airport, he immediately recognized the driver. It was a white housewife from Detroit who had joined the efforts and used her car to haul protesters to airports from their homes and college. Just hours after the third march, that housewife, Viola Liuzzo, would be killed by a sniper in the same car that LaFayette had been in three days earlier.

The Rev. Al Sharpton in Selma.

“Sir, could you please move off the street?”

I heard those words from a white Alabama state trooper this past Saturday morning, 50 years later. He gently guided me out of harm’s way on the curb and away from being struck by a security vehicle that was backing up.

Against the backdrop here in Selma for this commemorative jubilee, honoring those who endured so much a half-century ago, the officer’s simple gesture brought a smile. This weekend, there was much to smile about. As a 54-year-old black man, how could I not smile as I watched people of all races and faiths choking the streets near the base of the Edmund Pettus Bridge while awaiting remarks from the first African-American president, instead of choking on tear gas as many did some 50 years ago?

State police and local law enforcement officials from around Alabama supplemented federal units in protecting not only President Barack Obama, here for his remarks, but to keep safe the thousands here to commemorate — and more.

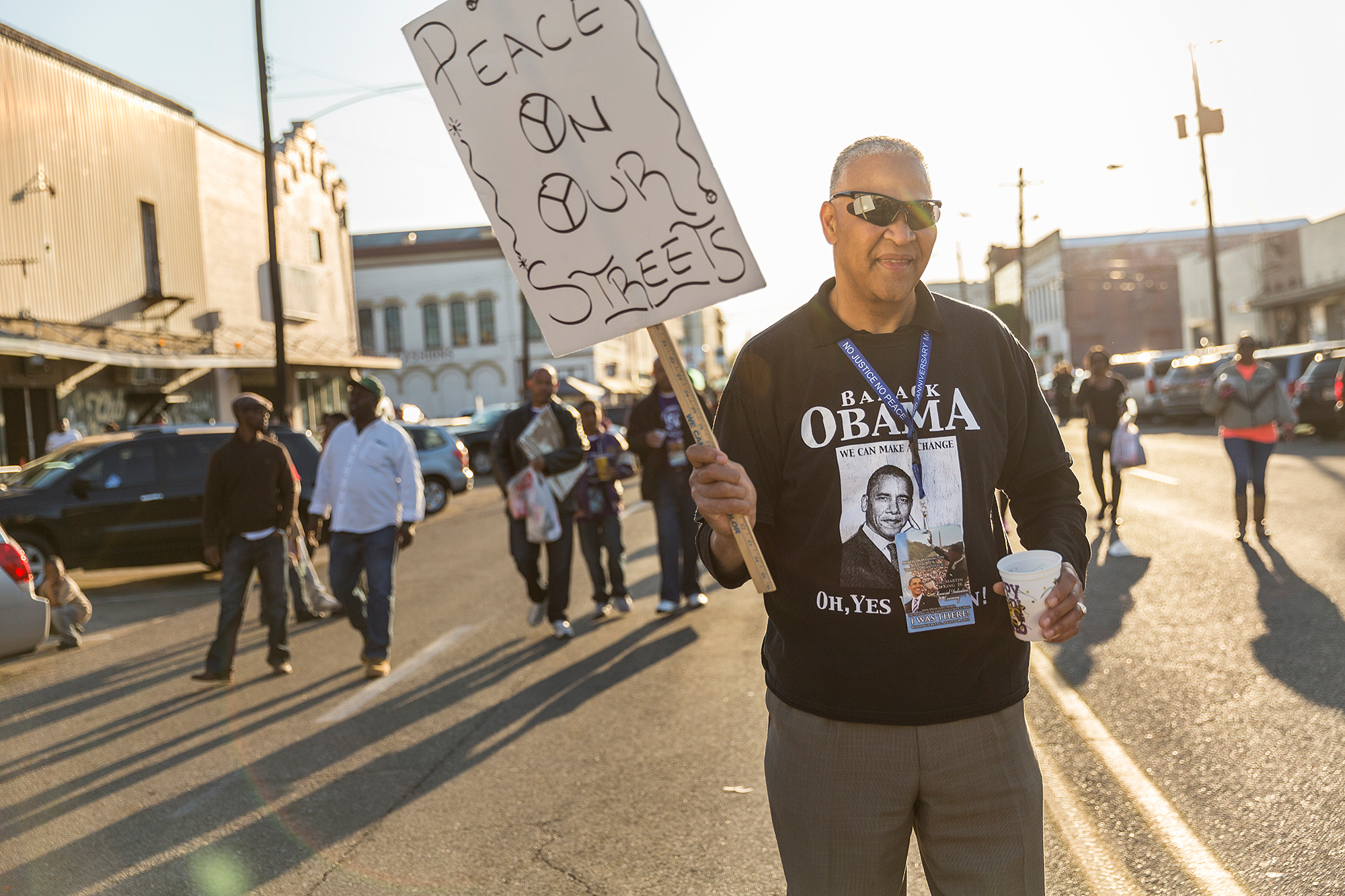

You had people promoting causes (the Teamsters, the National Organization for Women), those hawking programs and T-shirts (“Hands Up, Don’t Shoot”), the hapless couple cornered by the omnipresent conspiracy brother (“YOU DO KNOW MALCOLM X WAS KILLED ON JOHN LEWIS’ BIRTHDAY, DON’T YOU?”), and the sea of selfies being taken on the bridge where selfless sacrifices took place.

President Barack Obama speaks to a crowd of an estimated 70,000.

Evelyn Knight, now 81, came back to Selma from her home in Long Beach, Calif., for the commemoration. She was here 50 years ago for the second march, Turnaround Tuesday, and subsequent marches. When I asked her if she thought, because of the work she and so many others did to fight for the right to vote, that she’d live to see an African-American in the White House, she gave a non-traditional answer.

“Hell to the no,” Knight said, as Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” filled the air behind us. “But it’s a good thing. It’s good to see him talking that talk, and trying to walk the walk. As much as they’ll let him.”

Evelyn Knight, back in Selma 50 years after Turnaround Tuesday.

Knight had every intention of walking the walk on that Tuesday years ago, but there were greater plans in play. The marchers, led by Dr. King, left Brown Chapel, walked down what was then Sylvan Avenue for two blocks, cut right down Alabama for five blocks, made a left to the bridge, went over it, then stopped.

“Martin said, ‘We’re going to pray. We’re not going to go tonight because I don’t want to get you guys killed,’” Knight remembered. “We were scared what was going to happen to us was what happened to the people on Bloody Sunday.

“So when we saw them (state police), we knew they were not there for the welcome squad. We went back to Brown Chapel after we turned around. We didn’t know — because Martin didn’t tell us — that he was in negotiations with Lyndon Johnson to deputize the National Guard to accompany the people when they marched again from Selma to Montgomery.”

Fred Gray Sr., attorney to both King and Rosa Parks, did the heavy lifting that allowed the Selma-to-Montgomery march to proceed. He sued Gov. Wallace and the State of Alabama on behalf of the marchers beaten on their first march in the landmark (Hosea) Williams v. Wallace case. Based on Gray’s argument, Federal District Court Judge Frank Minis Johnson ordered Gov. Wallace and the State of Alabama to protect the marchers.

And with that decision, the third march was catalyzed. So many young people were among them, like a then 17-year-old John Rankin.

“We really thought a lot more people were going to be killed like Jimmie Lee Jackson,” Rankin said. “Scared? Were we scared? We sang, we got beat up. We had the saying, ‘Keep on keeping on.’ Believing that you can make it. That it was possible with hope.”

John Rankin was 17 years old when he did the Selma-to-Montgomery march.

If anyone can attest to the truth of Rankin’s belief and see it lived out before him, it’s Fred Gray Jr., an attorney in Montgomery and also my classmate at Morehouse College.

“This is a monumental weekend, actually, when you think about 50 years ago,” Gray said. “When you think about the marchers when they first tried to cross the bridge, they got all the way to the other side. And that’s when they got beaten up. You had that defeat. Then they got the victory that came a few days later. And today, we still struggle, but it’s a lot better than it was 50 years ago.

“But you also think about the struggles that we now have still. Voting rights is a big thing, and restoration of the Voting Rights Act is very key to us. And the economic gains that we have made vs. those that we still have to make. There’s a lot of work still to be done.”

Fred Gray Jr., whose father argued for and won a 1965 ruling that required the State of Alabama to protect the marchers.

It is that work that brought Evelyn Knight back.

“When I came here the first time, I was coming to get our right to vote,” Knight said. “It is unbelievable to me that I’m back again to try to protect our right to vote we’ve already won. We need to wake up. These folks are forever shitty.”

That is Lafayette’s fear — that people aren’t alert to things happening now that mirror what happened 50 years ago.

“The tactics have not changed,” LaFayette said. “Why do you think they put ropes around people’s necks to kill them? To shut them up so they can’t breath.

“Think about Ferguson and New York. They don’t want them to breathe because they don’t want them to speak up. For them to have a voice. The same thing with the chokehold. The man saying, ‘I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,’ and the man was still using a chokehold. If the man had kept his mouth closed and dropped his head, the police would have thought they succeeded. The vote is the same thing. The vote is a voice in government. Folks fought too hard to get it.”

My family and I live in Atlanta now, and we no longer make those trips from Columbus to Jackson over the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And that’s a shame. Despite what seemed like a lifetime of my chidings and admonishments into the back seat of our car, my kids failed to get it until my wife, Nannette, and I took them to Phipps Plaza for a New Year’s Day viewing of the movie, “Selma.”

The powerful film disambiguated for them what this slice of the Civil Rights Movement was about in ways I clearly could not. They sat rapt.

The lives of my three children — Cole, Dillon and Dailey — are so vastly different from those of the heroes, famous and not, who were depicted on the screen, yet by the looks on their faces, I knew they finally understood.

They also now understand that, really, they face their own struggles. They have their own bridges to cross. Same battles, different decades. They now understand why crossing that structure always struck such a nerve with me. For that I am wholly gratified, and oh so tempted to take a detour over that bridge one more time.

Because now, their eyes are wide open.

Tim Turner at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala.