Making Mom and Dad Proud

This Sunday, a little story from a born-and-bred Southerner who understands the sacrifices her Persian parents made to pave the way for her in America

By Sheyda Mehrara

When I was 7, those bubbles on the demographics portion of the standardized tests gave me anxiety. My parents told me I was Persian, but there was no bubble for “Persian.” I would cautiously darken the “Asian” option and pray no one, especially the SAT gods, would call me out for political correctness. Growing up Persian in the South created an early identity crisis — one that plagued my consciousness until I began to dig for my parents’ origin story, one that’s been difficult for them to recall.

It’s taken years of prying and leading questions, surely enough to land me on an episode of “Law & Order.” Regardless, I’m able to look back and still want more answers while my heart swells with a mixture of pride and duty to honor and revere my ethnicity – both as a Persian and a Southerner. If there’s anything a Southerner loves, it’s a good ol’ origin story that includes both heritage and sacrifice.

In 1975, my father, Mezhad Mehrara, decided he needed a change. The universities in Iran were notorious for exhaustive admissions processes and staggeringly low acceptance rates. He had a better chance of advancing his education in the U.S., and with friends already settled in Texas, he felt the warmth of the South beckoning. So four years before the notorious regime change in Iran, he moved to a small suburb of Dallas and quickly began his English language studies, in hopes of launching himself on a fast track toward U.S. citizenship. Citizenship would bring him his idea of a golden ticket – a university acceptance letter. That came soon, and he packed his bags for Fort Smith, Ark., to attend what was then Westark Community College (now the University of Arkansas – Fort Smith) to study industrial technology. The irony wasn’t lost on me that a quick Google search of ‘industrial technology’ is “the use of engineering and manufacturing technology to make production faster, simpler and more efficient.” Two years flew by and he moved to Sol Russ State University outside of Alpine, Tex., to be closer to friends and finish his degree.

When my dad admitted his story to me, I choked up. I was driving a Volvo and wearing Abercrombie, living in one of the most affluent neighborhoods of Birmingham. I had never experienced, as a pampered 16-year-old, true sacrifice but I was beginning to understand the concept from my father’s confessions as I applied for colleges. I knew in my stomach that I had never faced an insurmountable dilemma I had overcome only with sacrifice and dedication, as my father did.

When he was in school, even while he was managing a Dollar store in Alpine, he wasn’t able to support himself and send himself to school simultaneously.

Soon after, he began managing a Kettle restaurant (about which a Yelper has claimed, “Only reason you wouldn't like it is if you were from up North!"), and the opportunity to lead operations landed him in Memphis, Tenn. But a yearning for home and the family he was lacking in the States made him pack up once more and make the journey back to Iran.

Yet, home was no longer his anymore. The Shah had been ousted, citizens’ freedom stripped away and the rich culture inherited from the Persian empire left destroyed. His trips to visit friends who had been imprisoned for their ideas were enough reason to move back to the U.S.

Meanwhile, my mother, Sedigheh Seraji, had just graduated with a degree in environmental engineering from Pahlavi University in 1979, a year seared in nationalists’ minds because of the ousting of Reza Shah as the monarch of Iran and his replacement by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. It didn’t matter that my mother graduated from a university backed by the University of Pennsylvania; if anything, that made things worse in the eyes of extremists who deemed anything American evil. For two whole months, my mother was not allowed to work or exercise any of the freedoms she enjoyed prior until the government allowed women to return to society under oppressive religious statutes,and to take exams that would allow them to become teachers or secretaries.

Shortly after that, her friends were imprisoned for speaking out against the government, and I believe it was then my mother knew that Iran was no longer hers. Through family, she was set up with my father, and their possible relationship became a beacon of hope when she heard of his life in the States. They spoke on the phone for six months before my father flew over to Dubai to see his sister and meet the woman who would become my mother. They dated for two months, and my mother began her journey to the United States where she would be afforded the same freedoms that were ripped from her youth.

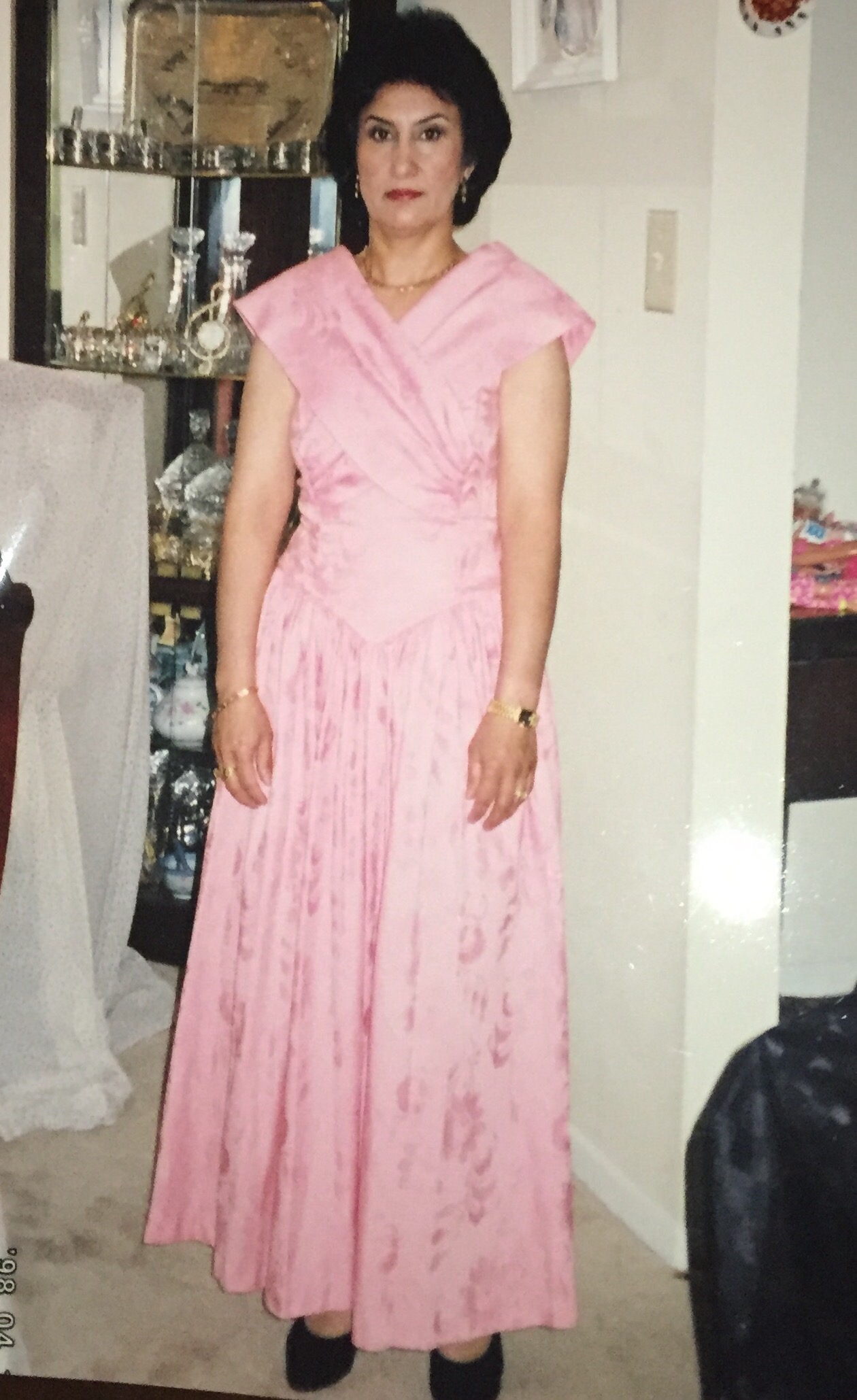

My father and mother arrived to a small, cozy home in Memphis in March of 1990. A year was spent adjusting to the unfamiliar faces and laws with sore, homesick hearts, but my father would take her out every Friday night with friends who would become new family. Almost a year later, news came that she was pregnant. Together, they were elated to start a family of their own. It’s something that Persians and Southerners share – a desire to grow bloodlines and a duty to those sharing a last name. Not only was my father estranged from most of his family, but neither of my parents had immediate kin nearby. I would love to give myself credit for bringing joy into my parents’ lives, but I’ve come to appreciate that their sense of building their own family was itself enough. The U.S. might not have had her beloved rollet cake from the corner bakery in Shiraz, but it did have Baskin Robbins. Three days wouldn’t pass without my father driving to one to grab caramel ice cream to satisfy some sort of hormonal craving, and he was happiest doing so. The pattern continued when my brother was conceived almost exactly three years later.

I know my father as a man with the cheeriest of dispositions even though none of his business ventures here in the U.S. have embodied the three things that make his eye glow: his music, his ability to fix any watch and his family. My mother became a licensed cosmetologist out of boredom and necessity. When she first moved to the U.S., the government wouldn’t recognize her diploma as an environmental engineer or a teacher. She was never able to practice the skills she worked so hard to acquire.

It’s still difficult to accept my mother’s incessant need to know exactly what I’m doing or why she still brings up the fact that I could have easily become a doctor, but it’s something I’ve come to understand. Both my parents bear a resilience that my generation is missing. I hold within me this burning desire to make them proud when I remember that their sacrifice has paved a path for me – one that is not clear, not smooth, but entirely full of opportunity they never knew.