Twenty-eight years ago, after scoring 11 No. 1 country singles, Rosanne Cash left Nashville behind, tired of the industry’s limitations. Ever since, she’s lived in Manhattan, made exactly the kind of art she wanted to make, and fought publicly against gun violence. Now in her 60s, Cash no longer gives much of a damn what anyone thinks about her, and she’s crystal clear about what she wants her life to be. We visited her Manhattan home for a long conversation about life, music, and the South.

Interview by Chuck Reece | Photographs by Caitlin Ochs

Rosanne Cash makes me feel like a fish, snagged hopelessly at the end of an angler’s line. She set the hook in my jaw 37 years ago with the song quoted above, and no matter how her career twisted and turned in the intervening years, I remained caught.

I expect this feeling stems from the fact that through the years, listening to her lyrics, I have often felt parallels between her life and mine. Cash’s second album, Seven Year Ache, which contained “Blue Moon With Heartache,” arrived midway through my college career. Critics everywhere prattled about how that album “pointed country music in a new direction,” which I thought was a welcome prospect. But my high hopes about new directions lasted only a week, which is how long it took for the Oak Ridge Boys’ dreadful “Elvira” to knock “Seven Year Ache,” Cash’s first No. 1 hit song, off the top spot on the country chart. I figure that must have been a hard week for Rosanne Cash. “Seven Year Ache” hit No. 1 the day before her 26th birthday, and six days later, she got Elvira-d. But as much as I loved the title song of Seven Year Ache, it was “Blue Moon” that landed firmly inside my heart. I can’t say for sure why. Maybe I wanted to be a diamond in someone’s eyes again. I don’t remember, and whatever it was, it matters not, now that I am 57 years old and Rosanne Cash is 63.

What I can say for sure is that through her entire career, Cash’s songs addressed things I cared about and lived through. The internal struggle between the pull of New York City and the pull of my home. The pain of losing spouses, fathers, mothers, and friends. The renewed sense of faith and optimism about the South that came to me in my 50s. Her lyrics have addressed all these things — and strangely at about the same times when I needed them addressed.

When the release of her latest album, She Remembers Everything, was announced, I lobbied Cash’s publicist for a long, in-person interview. I wanted a face-to-face conversation with an artist whose work has sustained me when I needed it for almost 40 years.

I suppose it did not hurt my cause that Cash has, for a long time, supported the work of The Bitter Southerner. In fact, I didn’t even need the publicist to give me Cash’s home address.

“It’s in our system,” I told the publicist, “from when she renewed her membership.” I found a “Better South” sticker on Rosanne’s refrigerator to prove it.

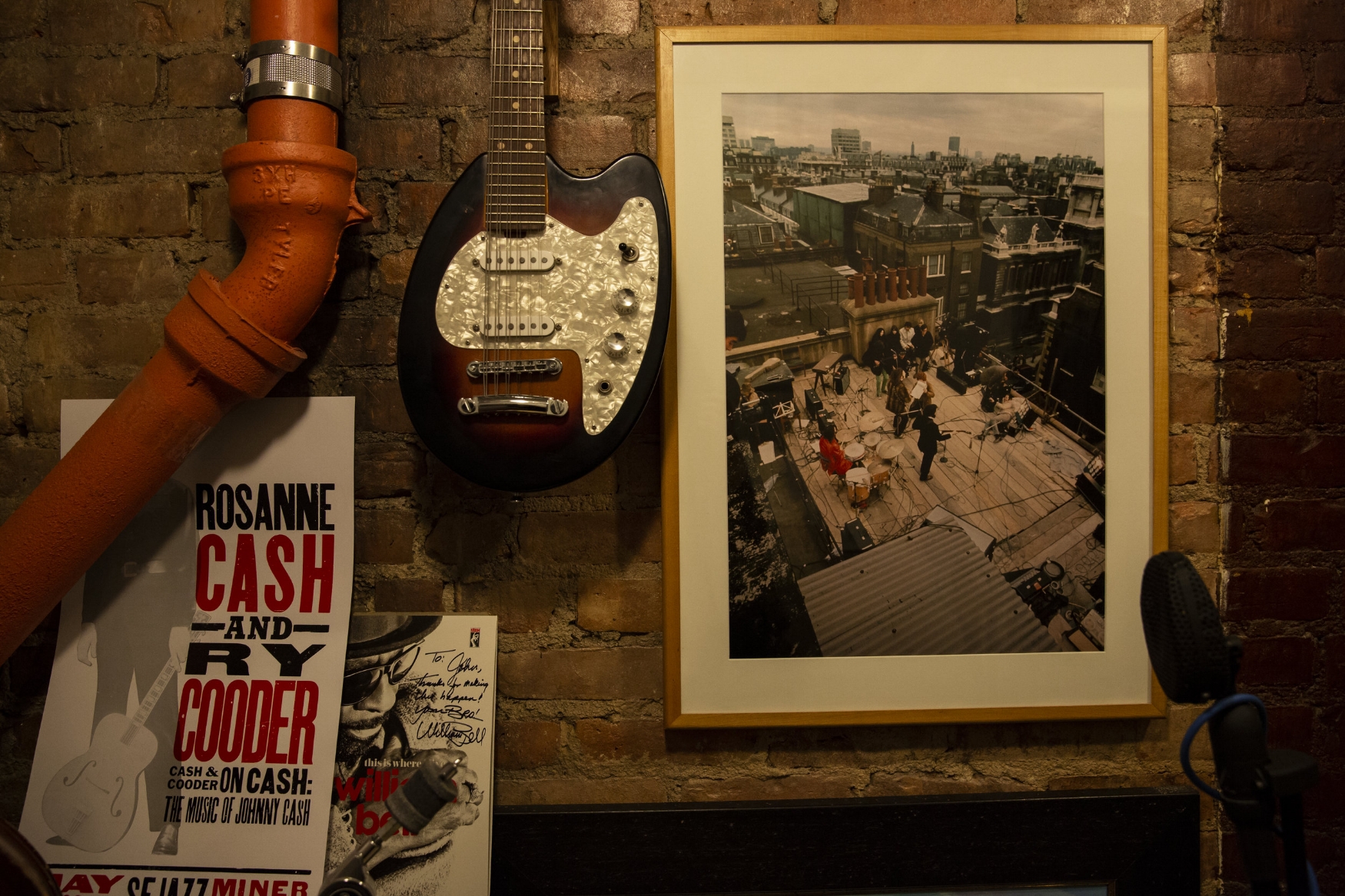

This interview occurred the day before Halloween, on a bright fall morning in Manhattan, in the home Cash shares with her husband and musical collaborator of more than 25 years, John Leventhal. Cash and Leventhal’s 1855 brownstone in Chelsea brims with musical instruments, books, and dozens of family photos of Cash and her five children. Sometimes, as you meander around the living room, you’ll spot a photo of those kids with their grandpa. His name, as you probably know, was Johnny.

In Cash’s living room, the prominent spot above the fireplace is held by Portia Munson’s painting “Knife, Elbow, Tree,” which the artist reconfigured for the cover of Cash’s new album.

Chuck: First, please tell me about the knife on the cover of this new record.

Rosanne: Well, this is Portia's original artwork, and she calls it "Knife, Elbow, Tree." I love her artwork, and I knew her work. She does very deeply feminist and nature work. And she did this installation in a gallery near here called the Pink Project. It was this huge explosion of these kind of girl fetishes and female fetishes, you know, like Barbie dolls and bras and just all kinds of stuff with this pink washed over it. It was incredible. So, I loved her work, but I didn't know her. So I just sent her an email out of the blue: “Would you be interested in doing an album cover?” And she said, “Yeah, I've never done that before.” I said, “Well, my favorite piece is this one. Do you think you could kind of deconstruct it for the cover?” I had an image of the knife falling into my hands as if I was one of the Greek oracles and I was getting something conferred, some kind of information and protection — not violence, but protection and power.

Chuck: See, I wasn't sure if you were giving the knife or accepting it.

Rosanne: I like that — that you don't know.

Chuck: Speaking of not knowing things, that's a good place to start a conversation about this record. I've been diving deep over the last couple of weeks not just with She Remembers Everything, but some of the older ones, because I've followed your career for a long time. I've been a fan for a very, very long time. The first time I heard "Blue Moon With Heartache," I was like, holy shit, she can write a song.

Rosanne: Thank you.

Chuck: Well, this album, to me, feels like there's a lot of mystery inside it. With most of the songs, I was having a difficult time — not that this was a bad thing — sussing out whether you were writing from your personal point of view or from inside different characters.

Rosanne: It's me, it's all me. I wrote about characters on The River and the Thread, and I made a conscious decision not to write in the third person about other characters on this record. That was one of my guiding principles.

Chuck: Oh, really?

Rosanne: Yeah. I wanted to return to personal songwriting. I had a lot of people around me going, “You should do what you did on The River and the Thread and make another concept record, make a record with a theme, you know? Make it so that art centers get it. You can sell something like that.” And I just didn't want to. Not that I didn't love making The River and the Thread, but it was part of this three-album cycle — from Black Cadillac [a 2006 release that chronicled the aftermath of her father’s and stepmother’s deaths in 2003] through The List [a 2009 album of essential country songs passed on to her by her father] to The River and the Thread [her 2013 reckoning with a changing South]. They were all themed, and I felt I had completed that. And I hadn't done an album of really personal songwriting since The Wheel [which was released in 1993].

Chuck: Well, I guess that's right.

Rosanne: The Wheel was the last one where I did a complete record of my personal songwriting. I wanted to be liberated from a concept and just write what was really in me, you know? And there was a lot in the last 10 years that happened. And not just in the outside world. I had major changes in my life over the last 10, 12 years.

Chuck: Like what?

Rosanne: I had brain surgery. [In late 2007, Cash underwent surgery to relieve a rare condition that had left her with debilitating headaches for decades.] That was a real scare with mortality that took me a long time to recover from. And John and I had our things. Like all long marriages, you hit a tough patch, and it takes some real work to get back. I had some stuff happen with my kids that was really painful that I just can't talk about publicly because they're not public figures. And on and on. I was re-examining my whole life.

Chuck: Those are all adult issues, and what She Remembers Everything feels like, to me, is a record made with the wisdom of an adult.

Rosanne: Yup.

Chuck: An adult who’s gone through a whole lot of stuff, much of it internal, but also one who is concerned about the external world. It's a set of songs, each of which addresses something specific and a little different, but there's something that holds them together. And now, I know that the thing holding them together is just your own life.

Rosanne: The one song that is written in character is “8 Gods of Harlem,” but even that is really personal to me, because I feel so strongly about gun control and so anti-gun violence. That weighs on my heart so much, and I try to do so much work in that field. So that song, even though written in character, is really personal.

Chuck: I wanted to ask you how that song came about.

Rosanne: Well, when I was recovering from brain surgery, and I was just lying on this sofa thinking about ... I was thinking about what I wanted to do, what work could lift me up. And I had this idea of writing a song with Elvis [Costello] and Kris [Kristofferson], who I've been friends with for decades. A song with both of them. I thought, “Well, that's weird,” but I kept seeing it, and so I just emailed Elvis and Lisa [Kristofferson] — because Kris doesn't email — and said, "Are you guys interested in writing a song?" They both said yes. And about the same time, I was going into the subway, and this Hispanic woman was coming out of the subway. She was walking with her head down, talking to herself. I don't speak Spanish, but I thought she said, "Ocho dios" — eight gods. And it was the A train to Harlem she was coming from, and I couldn't stop thinking about that. Ocho dios. Why would she say "eight gods"? I couldn’t get that out of my head. So the song just came out as “8 Gods of Harlem.” I feel so strongly about gun control, and I was thinking about when a child dies from gun violence, it's not just the families’ lives that are shattered, but it just resonates and ripples out to a community, to the city, to the world.

Chuck: That was the first song that really smacked me in my face. I felt like it's the most direct song on the album.

Rosanne: Yeah. It's very direct. The rest of them? You're right: There's mystery, there's ambiguity. There's kind of a female madness in some of it.

Chuck: One thing that struck me was this line that recurs at least in two of the songs — this idea of “thieves like us.”

Rosanne: Yeah. I mean you steal a little joy. You steal a little spot in the sun. You steal a little attention, maybe you weren't supposed to have. You steal a little success. You steal a little peace and quiet.

Chuck: Okay. Now I got to go back and listen to it again. (Rosanne laughs.) On this record, I also hear your writing maturing, and in the case of a few songs, it sounds like a direction that I hadn't really heard from you before. I’ve listened to “My Least Favorite Life” repeatedly, and it made me think of Leonard Cohen.

Rosanne: Oh, God, thank you. I bow down to you for saying that.

Chuck: Apart from family, who are the songwriters who most inspired you over the years, the ones who made you think, “I wish I could do that”?

Rosanne: Well, start with the Beatles. I deconstructed how those songs were written, both rhyme schemes and the way the choruses and the lyrics were set up, and that was the first imprint. And then Joni Mitchell, of course, because it was the first time I realized a woman could be a songwriter. Before then, the ones that I took in, they were all men. And it was inspiring: Not only could a woman be a songwriter, but her inner life was legitimate art to put out in the world, in a public sphere, and that was not only legitimate, but it was elevated to art. That changed things for me. And then, you know, I loved Neil Young so much. I loved Tom Rush. Kris Kristofferson. I loved Mickey Newbury. Lucinda [Williams], Steve Earle, Colin Meloy. And Leonard Cohen, of course. I think “Hallelujah” is one of the greatest songs ever.

Chuck: Yeah, I'm almost sorry that it’s become so ubiquitous.

Rosanne: I know. Same here. I’ve stopped doing it for a decade so we can re-hear it. Then, there is the really deep, deep stuff like Washington Phillips, the Carter family stuff, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, all that shit.

Chuck: That's like deep source material.

Rosanne: Those are the primary sources.

Chuck: Those are the headwaters.

Rosanne: Yeah. And then you come up all the way through Bob Dylan, of course. Do I have to even say that?

Chuck: No, that's a given.

Rosanne: But Lucinda is a freaking great songwriter. So good.

Chuck: Incredible. Yeah.

Rosanne: Lucinda and I have a love story together, you know. I just love her so much. I love her songs, and I think she feels the same about me, and we always just hug and kiss when we see each other. Like we were boyfriend and girlfriend — or girlfriend and girlfriend.

In the late 1980s, coming off the four No. 1 singles from her 1987 King’s Record Shop, Cash found herself wanting desperately to break out of the precisely defined boxes into which the Nashville music industry put women singers. So, she delivered Interiors, an album of spare, stripped-down songs that reckoned with the other big challenge in her life at the time: the slow unraveling of her marriage to singer-songwriter Rodney Crowell.

Chuck: I want to go way backwards. So you've lived in New York for 28 years now? Moved here in 1990?

Rosanne: Yeah, ’90 or ’91. I can't remember now.

Chuck: Interiors came out in 1990.

Rosanne: Yeah, and it was right after that when I moved to New York.

Chuck: I always felt like Interiors was a record that said, okay, I'm done with what came before.

Rosanne: Yeah, that's exactly right. That was a dark time in my life.

Chuck: What prompted that shift in your music and then the decision to move here to New York?

Rosanne: I think, unconsciously, I knew my marriage was ending. In fact, somebody wrote a review and said it was a “divorce record,” and I was shocked because I hadn't realized it. And then, of course, later on, I realized that he was right. So unconsciously, I knew that was going on. I was unhappy. I was unhappy living in Nashville and was not happy in my marriage. I didn't know what to do. I had kids.

Chuck: How many children did you have at the time?

Rosanne: I had them all except Jake, so there were four then. And I couldn't see how I was going to unshackle myself without hurting so many people. I just couldn't see it. But I was a New Yorker at heart. I always had been since I was a preteen. I knew it, and I longed to be here. I don't know how much of this story you want ...

Chuck: I'll take as much as you want to share.

Rosanne: Well, I gave the record to the label. I was really proud of it. I thought it was the best thing I'd done. I had produced it myself. I wrote these dark, kind of raw, acoustic songs, and they didn't want it. They said, “We can't do anything with this.” I was shocked, and then two or three months went by and they hadn't done anything, any marketing. And I was sitting on a plane looking out the window and thought, “I have to take control of this. I'm going down.” So I went in by myself, no manager or anything, to the head of the label (Columbia Records). And I said, “You have to let me go. Neither one of us is happy, and this is going to get worse.” I remember saying those words: “This is going to get worse for both of us.” And at the end of my little speech, he said, “Well, we’ll miss you.” That was it. Twelve years, like, done. I walked out of his office, and I was literally dizzy. I had to lean against the wall. I thought, “What am I going to do now?” I called my dad not long after that and said, “Dad, I got to get out of here.” And he said, “Screw ’em. You belong in New York.”

Chuck: He said that to you?

Rosanne: Yep. Those exact words. He just knew it. I mean, he had an apartment on Central Park South. He knew how much I loved the city. He loved the city. And so then it was a matter of extricating myself, trying to figure out how not to destroy my kids' lives. You know, how to unleash myself from a 6,000-square-foot house and a big diamond ring and a marriage that everybody had elevated to this kind of, I don't know, iconic entertainment. That was difficult.

Chuck: I had kind of forgotten about that, but yeah, that was a big public deal.

Rosanne: Yeah. I couldn't have a fight in public with him without it being written in the paper the next day. And I'm not kidding. It was many years of decompression and trying to find my balance and, you know, be happy again, and getting my kids up here, like one by one. That was excruciating.

Chuck: It didn't all happen at once?

Rosanne: No, it was excruciating.

Chuck: Where were you living when you first moved here?

Rosanne: On Morton Street in the Village.

Chuck: Morton and what?

Rosanne: Seventh Avenue. Not many steps from Matt Umanov Guitars.

Chuck: I will never forget sitting in Matt’s guitar shop one day when I lived here. I have always coveted a Martin 00-18. I'm not a great guitar player, but I've always coveted one of those. And I noticed he had one that was from 1945. It was in one of the glass cases. I asked him if I could play it, and he's like, "Sure." And so I sat down and started playing "Wildwood Flower" on it, and then suddenly, this thought hit me: How many thousands of ...

Rosanne: ... people have sat there and played "Wildwood Flower”? (Laughter.)

Chuck: And I looked at him, and I said, “I bet you've heard this too many times.” He was like, “Man, it's all right. It sells guitars for me." And I asked, “What do you mean?” He said, “More than once, I've had some man come in here and have to buy a replacement guitar because he spent so much time learning how to play ‘Wildwood Flower’ that his wife smashed his guitar.” That story reminds me of another question I wanted to ask you, one about "Wildwood Flower." I grew up in Appalachia. I grew up in the mountains of north Georgia, about 30 miles from where the Appalachian Trail ends. I grew up hearing serious, backwoods, Appalachian speech. But I still do not know what it means to “twine with my mingles.”

Rosanne: I don't know, either.

Chuck: You don't know, either?

Rosanne: (Singing a cappella) “I will twine with my mingles and waving black hair ..." It’s something about nature, but I don't know what it means. And it's weird that I never thought to ask June.

Chuck: That's funny.

Rosanne: And she had so many sayings that I learned, you know, that I didn't know until she told me. And that's one I never thought to ask.

Chuck: So, did you meet John after you moved here to New York?

Rosanne: I met John in Nashville, actually. He came down with Jim Lauderdale because Rodney was going to coproduce Lauderdale's record with John. It was so weird. Rodney was the producer, and he had been sent two demo tapes from two different people. One was this real straight country singer with real straightforward country songs, who was really good, though. And the other was Lauderdale, and he had sent some of the songs from Planet of Love. You know, those early songs. And Rodney couldn't decide which one to produce, and he said, “Well, which one do you think I should work with?” And I said, “I think that guy Jim Lauderdale. Those songs are really interesting. And I like what's happening on those demos.” It turns out [the musician on the demo tapes] was John Leventhal. Right? So John and Jim came down to Nashville. I was still with Rodney, but Rodney and I had already separated once. It was on its way out, and I met John, and this thought went through my head when I met him: “My life is going to get so complicated.” I remember that was the thought that ran through just like a train, life is so complicated, but we didn't get together for a couple more years, until after I had moved to New York and after Rodney and I were over. And then we started making The Wheel together.

Chuck: And The Wheel, to me as an outside observer, felt like a record about ...

Rosanne: Falling in love and lust?

Chuck: Um, yes.

Rosanne: Yeah, that's exactly what it was.

In 2014, Cash released The River and the Thread, an album that chronicled her travels with Leventhal to the Arkansas Delta, her father’s boyhood home, then to Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

Chuck: I want to go back to The River and the Thread a little bit. This is a publication called The Bitter Southerner, so you probably do have to talk about the South. I read and listened to and watched all the interviews you did about that record, and there was this idea that kept coming out in all of them — about how your travels there started opening you up to the South again.

Rosanne: Yeah. My heart was kind of closed to the South before I started writing the songs for The River and the Thread.

Chuck: Can you tell me a little bit about why it closed?

Rosanne: Well, I think partly because of living there when my marriage was dissolving, under constant scrutiny. It was constant. I started to feel so suffocated and so uninteresting and uninterested. My life had codified into something that was as far from being artistic as I could imagine. I felt like a fraud. I just had this huge record with King’s Record Shop. Four No. 1 singles. It sold really well. I had a ton of leverage with the record label, but I just felt like I had veered off the track of my life. That’s not to say I wasn't proud of King’s Record Shop, because I really was, but I'd only written a couple songs on it. When you think of yourself as a songwriter, and then you make a record that's truly successful, and there's only a couple of yours on there, I was a little shaken by that. I had to take some risks to get back to my correct path, and so I took the leverage I had with the record label to make Interiors. It was a commercial failure, but I was back on the right road, and I knew it. It didn't matter how it sold. I just felt suffocated. And I felt, too, that the South was too red, just too red. I didn't want to live there and have to hide myself. Back then, it didn't have the kind of communities that you have created — not very much, because the whole era of great Southern Democrats like John Seigenthaler and Al Gore Sr., the sit-ins at the lunch counters, all that was done. And the country music business had transitioned into some kind of conservative ideology and iconography that I just could not fly with.

Chuck: So what made you decide to dive back into the South with the making of The River and the Thread?

Rosanne: Arkansas State University called and said they wanted to buy my dad's boyhood home. There had been, originally, 500 houses left in this New Deal-era colony, but there were only about 20 left, and my dad's boyhood home was one of them. It was at the point of falling apart, and they wanted to get it before it fell apart. And they asked, would the family be interested in joining them in fundraising and supporting the renovation project? Well, I get asked to do a million projects about my dad, and this was the first one that really struck my heart. It had nothing to do with, you know, his iconic image and the projections that people put on him, trying to work their own agendas through him. It was about the source of him — and the earth itself. It was about "Five Feet High and Rising,” the gospel songs, losing his brother, everything that formed him. And so, I said yes. The first time I went down, we did this big fundraising thing. Marshall Grant [Johnny Cash’s bass player in the legendary Tennessee Two] showed up. He was like a surrogate dad to me. I stayed close to him my whole life. I loved him, loved him and Etta so much, and he was going to play the big stand-up bass in this show, although he hadn't been performing in a long time. And he came to rehearsal and played the bass, but he had a brain aneurysm that night. I sat with them in the hotel bar after the rehearsal with our arms around each other, and we talked. Then, he went to his room and had this aneurysm. And then he died a couple of days later. (Cash pauses to wipe away tears.) So we wrote "Etta's Tune" after that, because he had saved everything from his life with my dad from all those years of touring — everything, every ticket stub, every reel-to-reel tape, every program, every photograph, every backstage pass. They moved to Mississippi, and there was a house on Nokomis, which is mentioned in the song, where he kept all of these things safe. So John and I wrote "Etta's Tune.” I wrote the lyrics and John wrote the music, and my heart just broke open. And that's what started The River and the Thread.

Chuck: That's been four years ago now, right?

Rosanne: Almost five. It came out January 2014.

Chuck: How do you feel about the region today? How do you see it?

Rosanne: Well, there seems to be a spark there. I feel excited and in love with it. I do. I really do. I mean, that's not to say that I'm starry-eyed and don't see the realities of some really difficult, painful things. Do you know the Emmett Till historical marker still gets shot up regularly? Those things still happen, and it's so painful. But then there's the lynching museum and the Equal Justice Initiative, and there’s The Bitter Southerner. Nashville has become a foodie town, which is amazing. Single Lock Records and Natalie Chanin in Alabama. There's so much. The Savannah Music Festival. Dockery Farms. I mean there's a lot of things I'm thrilled about. It's awesome.

Chuck: My first job up here in New York was covering the media production industry for Adweek magazine. So, I was covering what then were the three television networks and the big magazine publishing companies. So I saw, you know, pilots that never made it on the air, magazine prototypes, that sort of thing. And the thing that always struck me was that every time I saw a television program that was set in the South or a magazine purporting to cover the South as a region, I only saw two versions of the South. One looked like, you know, a garden party and the other one looked like ...

Rosanne: … the Hatfields and McCoys?

Chuck: Yeah. Yeah. You know, there was The Beverly Hillbillies, from when you and I were little kids, up to Duck Dynasty more recently. And that wasn't the South I knew. I knew so many people who were between those things. And both those tropes ignored the diversity of the region.

Rosanne: Yeah, sure. That is the most diverse part of America. Mississippi is not the same as Charleston.

Chuck: But particularly over the last couple of years, I think I finally have a sense of who our audience really is: It's anybody who has ever felt like a misfit in the South. And we've given them a place, a community.

Rosanne: I feel tons of optimism about the South now, and a lot of love. I love going there. And I go a lot, to just soak up the sweetness and the people I know and feeling connected to the past, you know, my ancestry. You're not going to believe this, but I joined the Daughters of the American Revolution. I just went to my first meeting and was inducted. I did it. And you know why? Because of Trump, because of the immigration policy and how cruel and inhuman it is, and I thought to hell with that. My family's been here since the 1600s, and I have multiple ancestors who fought in the Revolutionary War, and I welcome all immigrants. So I just wanted to make a stand.

Chuck: I think the DAR needs people like you.

Rosanne: And my group here, the Knickerbockers, they are badass women. I mean, they can't publicly say anything political through the DAR. But they all went to the Women's March. They do more community service than anybody I've ever seen. I'm really proud of that. They are awesome.

Chuck: Maybe this was my own wishful thinking, but when I listened to The River and the Thread, I heard you questioning whether or not you ought to move back.

Rosanne: No, I couldn't do that.

Chuck: You're a New Yorker now.

Rosanne: I'm a New Yorker. You know, that thing you said about misfits. It's like, you know, "We always thought she was kind of weird. Turns out she’s just a New Yorker.” But you know, what's really moving to me about the South now is that there's no self-consciousness or embarrassment, no need to explain or have low self-esteem about being in the South. I mean I always got that feeling back when I lived in Nashville — kind of a regional low self-esteem. They were always trying to prove themselves or something. It just doesn't feel like that anymore. There's a real claiming of the peculiarities — and the beauty in those peculiarities. Like you.

Chuck: Well, thank you. But I ain't the only one. I just didn't know how many of us there were before we started this publication.

Rosanne: Y’all have done an amazing job. You've created community.

The evening before our interview, Cash staged a premiere of the songs from She Remembers Everything at an art gallery in Brooklyn. The songs were interspersed with readings from women who are part of the community Cash has built for herself in New York, including prize-winning novelist A.M. Homes, Maria Popova, the writer and founder of the endlessly fascinating blog “Brain Pickings,” and Staceyann Chin, the Jamaican-born poet, and LGBTQ rights activist.

Chuck: How is it these days to be a Southerner in New York City?

Rosanne: Well, I never considered myself a Southerner. I always considered that my parents were Southerners — and their parents and their parents and their parents. I only lived in the South for three years after I was born. I always considered myself a Californian, and then I moved to Nashville as an adult. When I first bought a house in Nashville, I met the landscaper, and I said, “Can you plant some bougainvillea around the front?” And he just looked at me and said, "You're not from around here, are you? You can't plant bougainvillea in Tennessee.” I mean, I have to say it wasn't until The River and the Thread that I started claiming my Southernness. I thought, man, this shit goes deep. It goes deep in me, and I claim it.

Chuck: Well, it made us happy when you did. The Bitter Southerner has become friends with Allison Moorer since she did the Word of South Festival in Tallahassee with us earlier this year. I was talking to her about a month ago and told her I was coming up here to interview you. I said, “Do you know Rosanne?” The first thing she said was, “Yeah, I'm in a sewing circle with her.” And I was like, "A sewing circle?” But then, the next thing she said was, “Ever since I moved here, Rosanne is the closest thing I've had to a mama.”

Rosanne: Awwww.

Chuck: So, there is that connection between you two folks with Southern roots, but I felt that community vibe when you were on stage last night with those other women. Even though those women were dramatically diverse from each other, that sense of community among you was easy to feel.

Rosanne: I'm part of the greatest community here. It's so deep and rich, and it goes from A.M. Homes to Allison to Gael Towey, who used to be the creative director of Martha Stewart Living, to Kay Gardiner, who's a knitting goddess who does a lot of stuff in Nashville even though she's a New Yorker, too. And it's not just the women. It's kind of endless. All the musicians I play with, it’s such a really rich community of people I love.

Chuck: And what else do you really want in life, but to be surrounded by a community of people who love you and whom you love?

Rosanne: It was something I dreamed of — this kind of community where you're sitting at a table with a novelist and an astrophysicist and a poet and an actress and a neuroscientist and a painter and a pianist. They all sit together and have a conversation that is vibrant and inspiring. Those were my dreams from the time I was a little kid. I want to know people like this, you know? I want to know the people who are really obsessive and passionate about different subjects, so they can teach me, and I can talk to them about it. You know, Lisa Randall, who's a theoretical physicist at Harvard, is a good friend of mine, and she'll dumb down and talk to me about quantum physics. Sheila Berger, a sculptor, she did this big bird for Riverside Park, and I went down into her workspace where she welds, and she showed me what she does. I mean, that kind of thing happens almost every day. I'm so lucky.

Chuck: Do you feel like, right now, you're in the best place you've ever been in your life?

Rosanne: Totally. I just wish I could do it without wrinkles.

Chuck: I think that comes with the territory. I don't think you've got any real wisdom until you have a wrinkle or two.

Rosanne: It's a small price to pay. That's true.

Chuck: I wanted to also talk a little bit about the points you made in your speech at the Americana Music Festival. When you did that speech, there are a few things that stuck out at me. The first was this idea where you said musicians are “the premier service industry for the heart and soul.” I liked that, because it was you telling people that their work was not frivolous — and not only by an artistic measure but an economic measure.

Rosanne: Not only an economic measure but by service standards. We provide service. We're not just out there being little whirling dervishes of narcissism so that we can have your attention reflect back at us. We're in the service industry. You come to us to access your feelings and get your life reflected back to you. That's what we do.

Chuck: Which allows the listeners to move someplace else. It allows you to move on through your life. Right?

Rosanne: The value is, of course, that we need for fair compensation because we're valuable members of society, just like everybody else. You know, you don't ask your plumber to work for free, or your lawyer, or your kid's teacher although they work almost for free. And you shouldn't ask artists to, because we provide a service that's also important.

Chuck: Now the second thing from that speech was about women. It was something you brought up again last night. You said women have unique gifts and if you just count out half the whole world, it tilts on an unnatural axis. Now, when I heard that line, it felt absolutely true to me, but I would love for you to talk a little bit more about what you were thinking when you said that.

Rosanne: Let me see if I can articulate it better than that. If only one half of humanity — it's not even half, because black men aren't valued equally either — but if only one group is valued, things start to tilt. You know, it's like if you only had one food in your diet, you'd become vitamin deficient at some point. With everything else, you are missing out when you don't take advantage of the richness of what women can offer the world. We don't think just like men. We don't. We don't have heart disease just like men. We don't assimilate medicine like men do. We're not small, inferior versions of men. We're different, and what's happened over the millennia is that the differences have been judged to be inferior. But they're not inferior.

Chuck: They're part of the balance.

Rosanne: They're part of the balance, and that's why everything is so fucked up now because there's no balance.

Chuck: I think you're right. I also think that what we're going through now, it's going to take a long time, but we're sort of in the middle of the dying bellow of the old-white-man patriarchy. I mean its fall is demographically inevitable.

Rosanne: Kurt Andersen said to me a couple of weeks ago it's the last gasp of a dinosaur and that's not to say that men are bad or have to go away. It's not about male bashing. I mean there's plenty of women in the white male patriarchy as well.

Chuck: But there's a lot, I think, that men like me are still learning about how to treat all women with the respect they actually deserve.

Rosanne: So is my husband. He actually said, “I'm learning. Teach me.”

Chuck: It's ridiculous how much we assume, how we just go on behaving in a certain way because we’ve always behaved in that way and we didn't think anything was wrong with it. Nobody ever pointed anything out.

Rosanne: And think about the more malignant parts of that. Like all the things that happened to me when I was a young artist and the things that promotion guys and radio guys said to me, did to me. I just kind of like went on, you know, like letting it bounce off of me, trying to protect myself. Never really thinking, just not even thinking about it. It's just part of what you had to deal with. And now, during the #MeToo movement, men started thinking about all of that stuff for the first time really. When all that stuff with [Harvey] Weinstein was happening, John said, “I don't know any men like that.” I said, “Yes, you do. You just don't know that you know them.”

Chuck: Well, you know, one of the things I think has been happening, too, at least among decent man, and I count myself among them, or try to, is that you start looking deeply back into your life. I mean the culture when you and I were growing up was very different than it is now. And I keep looking back into my memory going, did I do anything?

Rosanne: I think a lot of men did that, Chuck, and were confused about like, was that inappropriate? Was it just because it was a different time, you know? And I get that, totally. There were men I knew who came to me and asked, “I did this thing once. What do you think of that?” I'd go, "It's okay, you know. That was a different time. Nobody told you not to do that."

Chuck: Yeah. Now, onto the one last point, you made in that speech. You said, “I have a surplus of righteous indignation, and I'm too old to care about it anymore.”

Rosanne: [Laughs] That speaks for itself.

Chuck: It really does, but I have to say, to me, as I approach age 60, I'm feeling a good bit of liberation myself.

Rosanne: Hell, yes! And if you don't feel liberated at this point to speak your conscience, then something's wrong. What's the point? Exactly what's the point? Just go sit in front of the TV until you die. That's exactly how I feel. I feel an urgency about it. To hide my convictions is morally wrong.