Where can you find the real Florida, the old Florida, in that state’s tangle of tourist attractions and generic beach condos? And if you find it, should you tell anyone else about it? A three-generation team of women in the Florida Panhandle have just self-published an uncommonly ambitious, genre-defying book, “Saints of Old Florida,” that attempts to capture the magic of their little slice of the southernmost state. They are absolutely correct in their feeling that their stories should be told. They’re just a little worried that folks might get mad because they let the secret out.

Words by Chuck Reece | Photographs by Lean Timms

I suppose you could call it a dune buggy, this vehicle that’s bouncing me to and fro in its backseat as it trundles along the beach — eastward on a peninsula that juts into the Florida Panhandle’s Apalachicola Bay. It looks like a golf cart with two exceptions: wheels that sport tiny versions of tractor tires and a sturdy steel roll cage, just in case.

The fellow driving it, Danny Gilbert, was a linebacker for Bear Bryant and captain of the 1970 Alabama Crimson Tide, which was less notable for its record (six wins, five losses and a tie) than it was for being the first Bama football squad to offer scholarships to African-Americans. Gilbert, now in his 70s, grew up in the tiny Northeast Alabama town of Geraldine. After college, he did well in the business of installing and maintaining municipal water systems, and he and his family have made a nice life here in this little stretch of Panhandle paradise. Like me, he’s a mountain boy who loves the salt air.

As we bounce along the white sand in Gilbert’s whatever-you-call-it, I take a short Instagram video of the waves rolling in. I post it, tagged with our location. Before long, a comment appears.

It says, “Shh. Secret place.”

Florida, oh, Florida. What to do with you?

For so many landlocked Southerners, yours are the first beaches we ever see.

You beckon us with your gaudy charms, your Islands of Adventure, your Magic Kingdoms, your Wizarding Worlds.

You are our first bad sunburns.

You alone can turn a bunch of old-folks homes on a beach into the playground of the most vainglorious people in the whole, wide world. And do it in less than 20 years.

You pave paradise at a speed Joni Mitchell never imagined.

You get tackier every year.

Ah, but somewhere inside you, somewhere in your befouled and abused spirit, there are clues to what you really are, what you were before Uncle Walt, what you were in the days when we never argued about whether our southernmost state was actually Southern.

But where to look? You have 1,350 miles of coastline and 53,927 square miles of territory. That is the question: Where can we find you, Florida? I have visited you, been on your islands and keys, stayed in your little motels and your Eden Rocs, explored you on the cheap and on the expense account. Florida, I have looked for you for 50 years, since I was a child.

I think I have found you. I feel your old, good heart beat strongest in …

Oh, but wait. It’s supposed to be a secret place.

Shh.

Enough with this “secret place” business. You can’t tell people that a place matters without telling them where it is. To do so is neither fair nor fitting.

So, where is this “Old Florida” of which people speak?

In my opinion, it’s three counties in the Panhandle, Gulf, Franklin and Wakulla — pretty much everything from the Apalachee Bay, south of Tallahassee, westward for about 125 miles to Mexico Beach. Farther west, you run into the recently built new-urbanist communities like Seaside and Watercolor and then the Redneck Riviera hubbub of Panama City. Such modern activity hasn’t encroached quite so much on the Old Florida of Gulf, Franklin and Wakulla counties.

Here, most people have deep roots in their communities and deeper connections to the water, which has fed them and their families forever. Even as tourism and real estate have become the prime drivers of Florida’s economy, the Panhandlers still know how to mend fishnets and tong for oysters. The real-estate prices keep rising, of course, but still, somehow, nothing about these coastal communities feels exclusive. Folks here are more likely to name a house “All Conched Out” than, say, “Mar-a-Lago.” The place still has an abundance of what Miami New Times writer B. Caplan once called “Florida's primary natural resource … bizarre-as-fuck-ness.” Doesn’t matter much how weird you are; if you move to this part of Florida and find a way to make a living and a home, you’ll be as welcome as the fifth-generation folks.

No wonder some people want to keep this place a secret.

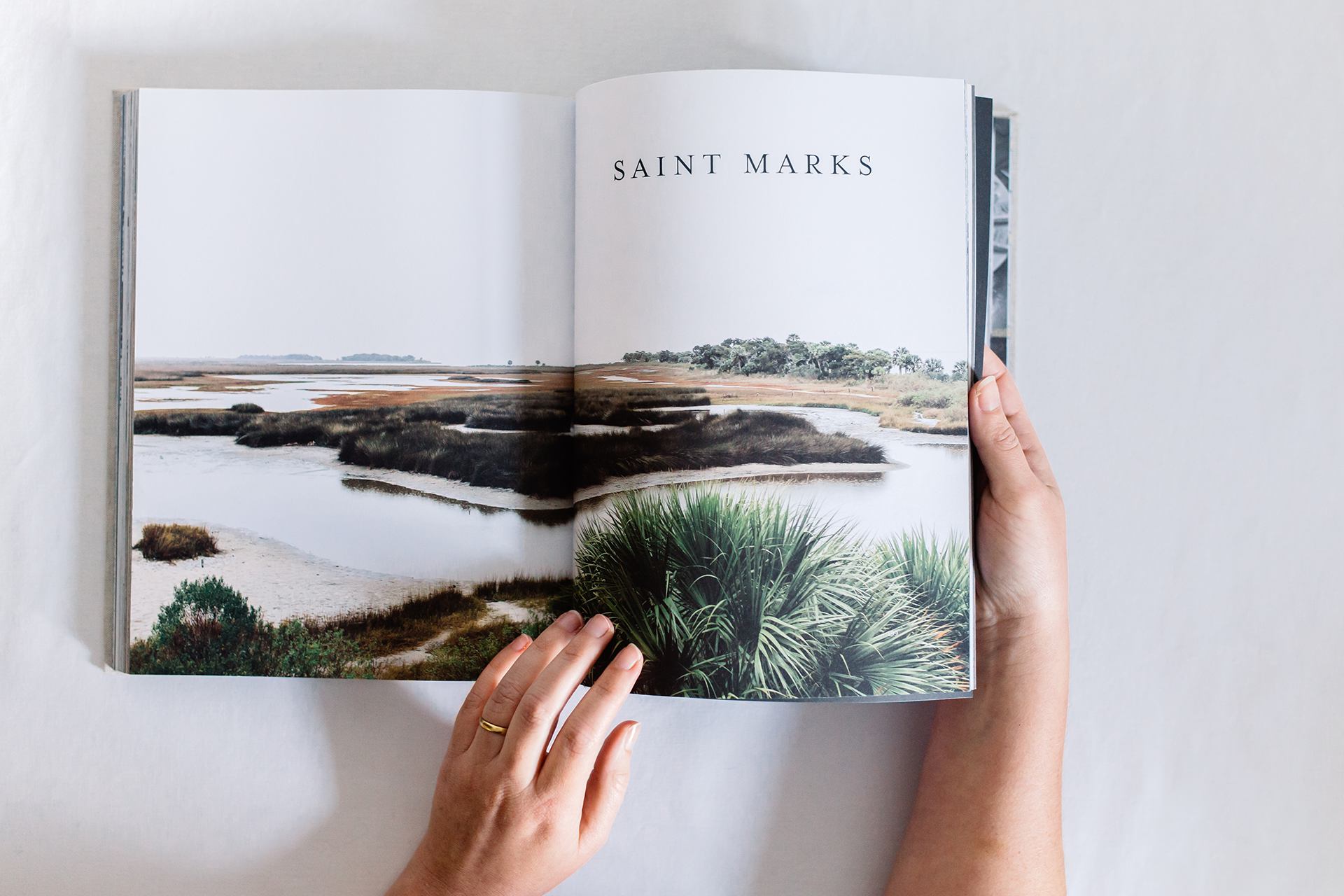

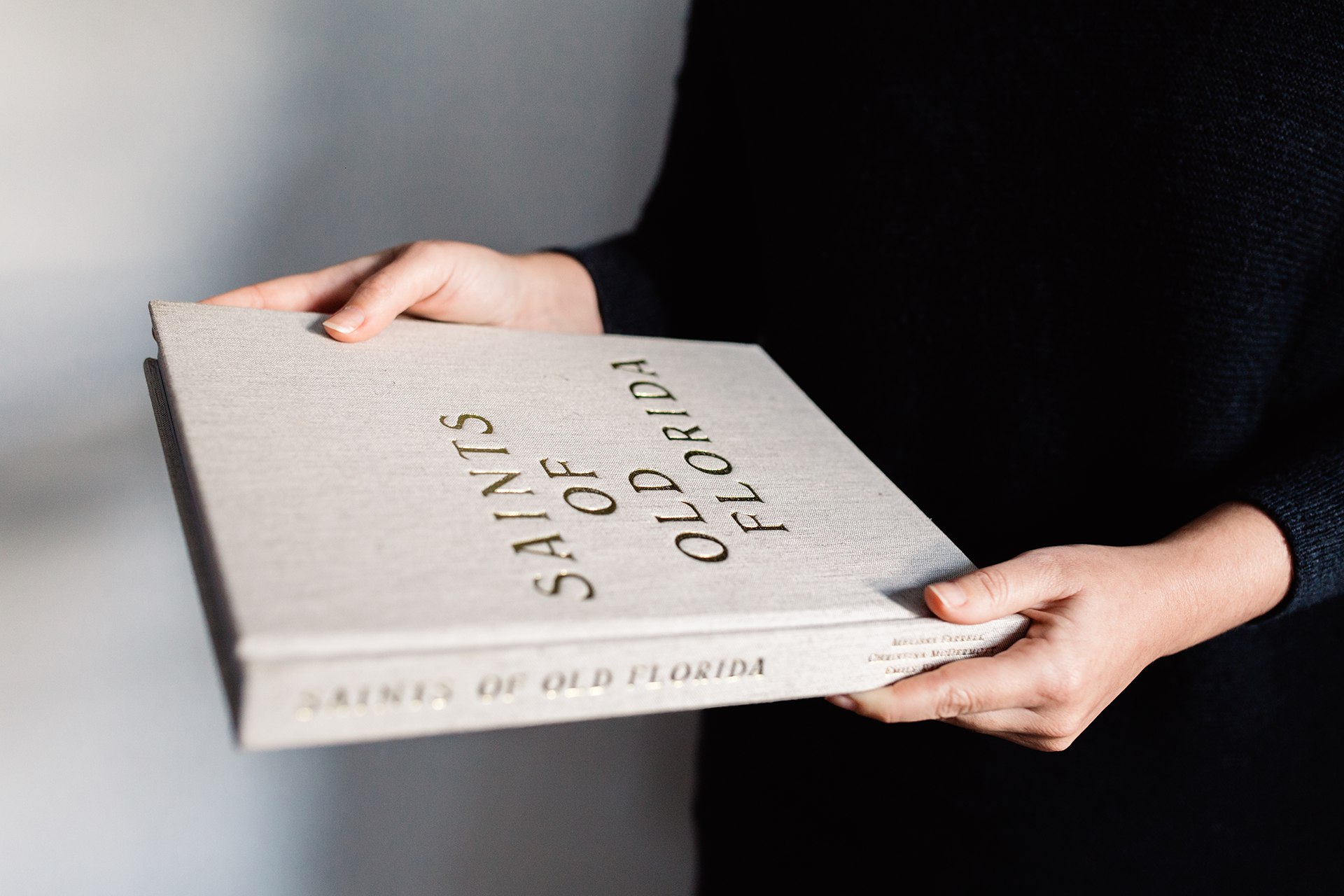

But many who grew up here — and others who were drawn to make it home — care deeply about documenting the stories and rituals of this place. Today, those people get a document they probably never envisioned: a rather remarkable, whopping book called “Saints of Old Florida,” by three women of three generations who call Gulf County their home. “Saints” is a self-published, unlikely labor of love: full-color, hardback, three pounds, the kind of book that hits your desk with a thump. Its 250 pages are filled with the stories of Old Florida’s people told in their own words, plus beautiful new photographs, collages of old snapshots and several recipes that’ll help you eat like they do.

New York City publishers would probably characterize this as a “style book.” If forced to confess my own preferences, I’d admit that style books generally make me gag a little. They typically portray ways of life largely inaccessible to the average Joe or Jane, and that gets under my skin. It is true that “Saints of Old Florida” will reward page flippers in search of a good decorating idea, but this book reaches deeper than the typical style book. It has the grace not to attempt telling the stories of the place’s natives from a removed, ain’t-the-old-ways-cute point of view. Instead, the three authors — Christina McDermott, Melissa Farrell and Emily Raffield — allow the people of Old Florida to tell their own stories in their own words. Other books might approach the almost 40-year-old Spring Creek Restaurant in Wakulla County’s Crawfordville by praising its “quaint” location and its “authentic” food. The “Saints” authors instead invite Clay Lovel, who grew up in the family restaurant business, to write his own story.

No wonder McDermott, Farrell and Raffield decided to publish “Saints” themselves. Their book defies the publishing industry’s formulaic categories.

They begin its introduction this way:

Sacred tradition and the restorative elixir of salty air — that is the spirit that holds all we love together. It is what inspired our ancestors to make miles of roadway and coastal scenery into home, and it is the essence we long to capture, bottle and share. This book is an expression of our love and reverence for this part of the world.

What were they thinking? It was supposed to be a secret.

The authors of “Saints of Old Florida” constitute an unusual team. At age 66, McDermott is the oldest. Thanks to her father’s job, McDermott grew up on “Gringo Row” in Monterrey, Mexico, and finally, about a decade ago, found home on the Panhandle. Farrell is 48, a native of Thomasville, Georgia, who moved to Port St. Joe 15 years ago and opened Joseph’s Cottage, a retail shop that sells home goods, many of them locally made. The youngest, at age 27, is Emily Raffield, a fifth-generation Floridian who could skip a stone into St. Joe Bay from her childhood home’s back porch.

The three women came to know each other about two years ago through Farrell’s store.

“Joseph's Cottage is like the one kinda cool shop here in town,” Raffield says. “I’d always go in there when I’d come down here on the weekends to see my family.” Then, two years ago, Raffield decided the corporate marketing life in Atlanta, where she’d made a living since college, was no longer for her. She returned home to Port St. Joe and wound up working at Joseph’s Cottage on occasion. By that time, McDermott was also working periodically at the Cottage.

McDermott and Farrell had been toying with the idea of creating a book about their home, but after Raffield returned to Florida two years ago, they invited her into the project, and only then did work begin in earnest.

“Literally every single day from that point on has been an evolution,” McDermott says. “Was this going to be just a historical book? Or just recipes? Or was it going to be kind of a novelty, a gift item?”

christina mcdermott

Melissa farrell

Emily Raffield

The more they worked on the project, the more they realized they were trying to capture something far more ineffable than a cookbook or even a deep historical account could handle. They were trying to capture the spirit of the place.

“When I graduated from college,” Farrell says, “I moved out west, I moved to the Northeast, I moved to the Pacific Northwest, then I moved to the Charleston area, and then my husband and I lived in Thomasville for a few years where all my family is. But the minute we moved here, just walking on the beach it was like ... it's hard to explain, but it just always felt like home. Then just having that content feeling of being here for over 15 years, I don't know, it's hard to describe.”

I’d have to agree. I’ve been coming to this part of Florida regularly for almost 20 years now, and never seem able to leave it without contemplating, even if only for a moment, selling everything I own and moving there. Perhaps I do this because, after my own years of wandering, I decided I belonged in the South, and in this part of Florida, you never wonder if you’re really in the South. In these three counties, you are very much in the South. But these places are also blessed with that Weird Florida thing. Here, you will see a sunburned old man slowly pedaling a banana-seat bicycle down the highway, one hand on the handlebars and the other holding a beer, weaving a bit, and you will not call 911. Instead, you will just have a chuckle and be on your way.

“There isn't the pressure to be perfect here,” McDermott says. “There isn't the pressure to pack the right things to go to the beach and have your perfect beach chair and your special bathing suit — like you would at the beaches that are west of here. That's not what this is about. This is about coming in your old T-shirt and shorts and your flip-flops, and hanging out and finding places to eat or people on the beach who will invite you over to their fire pit. It's very casual. It's very accepting, and it's such a good feeling.”

Gulf, Franklin and Wakulla counties, of course, face the same questions every part of Florida has been forced to consider: How do we preserve what we love in the face of development? How can our sons and daughters make lives here without new economic forces? Is it worth preserving at all?

Clearly, the authors of “Saints of Old Florida” believe it’s worth preserving; that is the singular purpose of their book. But one of the things that make “Saints” a different beast than a “style book” is how it unearths the stories of younger people who’ve made conscious, deeply considered decisions to remain in family businesses there.

A particularly affecting section of the book is a long interview with T.J. and Sara Ward, both of whom made the tough choice to stay in the family’s oyster business, Buddy Ward & Sons. In the story, Sara Ward says, “I worked at the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina for a bit. I really enjoyed it and was using my degree, but I felt like I was missing out on so much at home.”

Says McDermott: “There aren’t a lot of ways to make a living here. But those two children went to FSU and had huge futures and could have lived anywhere, and they decided to come back and help their dad continue to run his oyster business. They had the same feeling. There's something about this area that draws you back over and over.”

Such a choice is no small thing for young people such as Sara and T.J. Ward. They’re having to readjust the business to new realities brought about by everything from environmental disasters to a never-ending stream of changing regulations from the federal and state governments. A quarter-century ago, Buddy Ward & Sons shipped oysters and shrimp nationwide. Today, their reach is largely local. They’ve had to shift the business from a wholesale-only operation and open a retail seafood market in Apalachicola, Franklin County’s largest town. That market, Sara says in “Saints,” has “turned out to be really great for us.” Still, theirs is a major business exercise, retooling the family enterprise for new realities.

In big cities, you can get paid a lot of money for that kind of business expertise, but the cities bring with them a swarm of pressures not present in this part of Florida. In the big cities, it’s about background and credentials and whether you are “a good fit” inside a company’s culture. Here, the challenge is singular — how to keep the family business afloat — and you need not worry about the other stuff, because everyone is a good fit here.

“One thing that Melissa has always said from day one is that people feel a sense of acceptance here, no matter where you come from, no matter your background, no matter just anything,” Raffield says. “It’s not that thing like, ‘Well, nobody asks you any questions here.’ It’s more like, people just have this camaraderie, and it's like …”

She pauses.

“It’s like a grace.”

My wife and I visited Port St. Joe on Memorial Day weekend to be there for the dinner celebrating the publication of “Saints of Old Florida.” The authors and about a dozen of their friends and families gathered at the home of Danny Gilbert, the old Bama linebacker, and his wife, Mindy, out on the Indian Pass peninsula. Their house, back on the lagoon side of the peninsula, is where the Gilberts plan to spend the rest of their lives. Danny Gilbert is the sort of host who likes to stand behind the 100-year-old bar he salvaged and installed in the kitchen, dealing out drinks, stories and jokes. He poured me a mix of sweet tea-flavored vodka and lemonade. He had a name for the drink, but after two of them, I did not remember it.

I knew my wife could soberly get us back to the little apartment above the garage at Raffield’s parents house, our redoubt for the weekend, but I wondered how folks without a designated driver handled nights like these.

“There’s no Uber here,” I said.

“There’s definitely no Uber here,” Raffield said, “but there’s no cops, either.”

That’s the thing about this part of Florida. When you get there, the whole place seems to say to you, “Just roll with us. You’ll be fine.”

Walking out of the Gilberts’ home, I noticed a wooden sign above a doorway bearing what looked like the name of a Scottish town. It said, “Dunworryn.”

Done worryin’. I walked out into the cool Panhandle night. I was done, too.