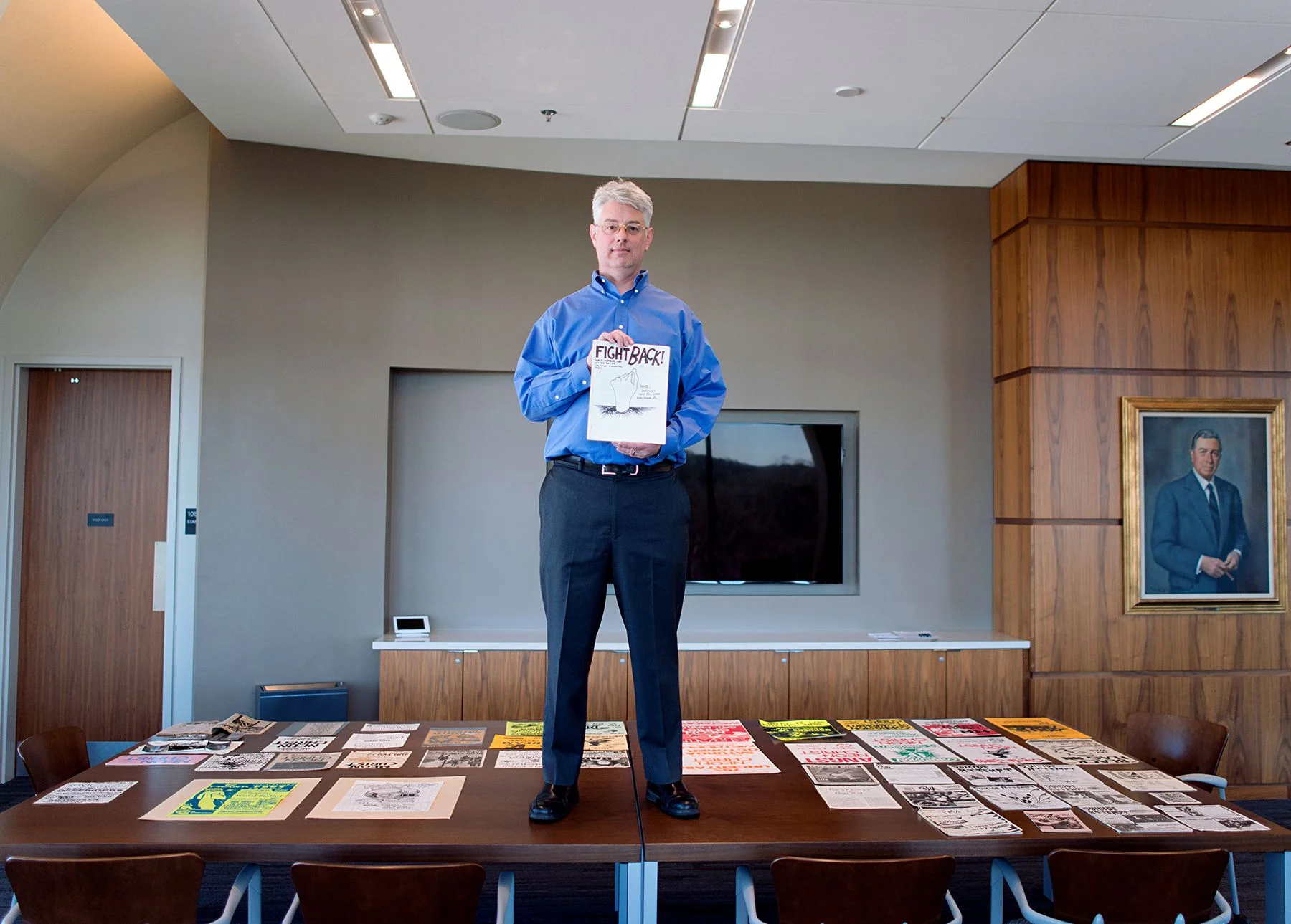

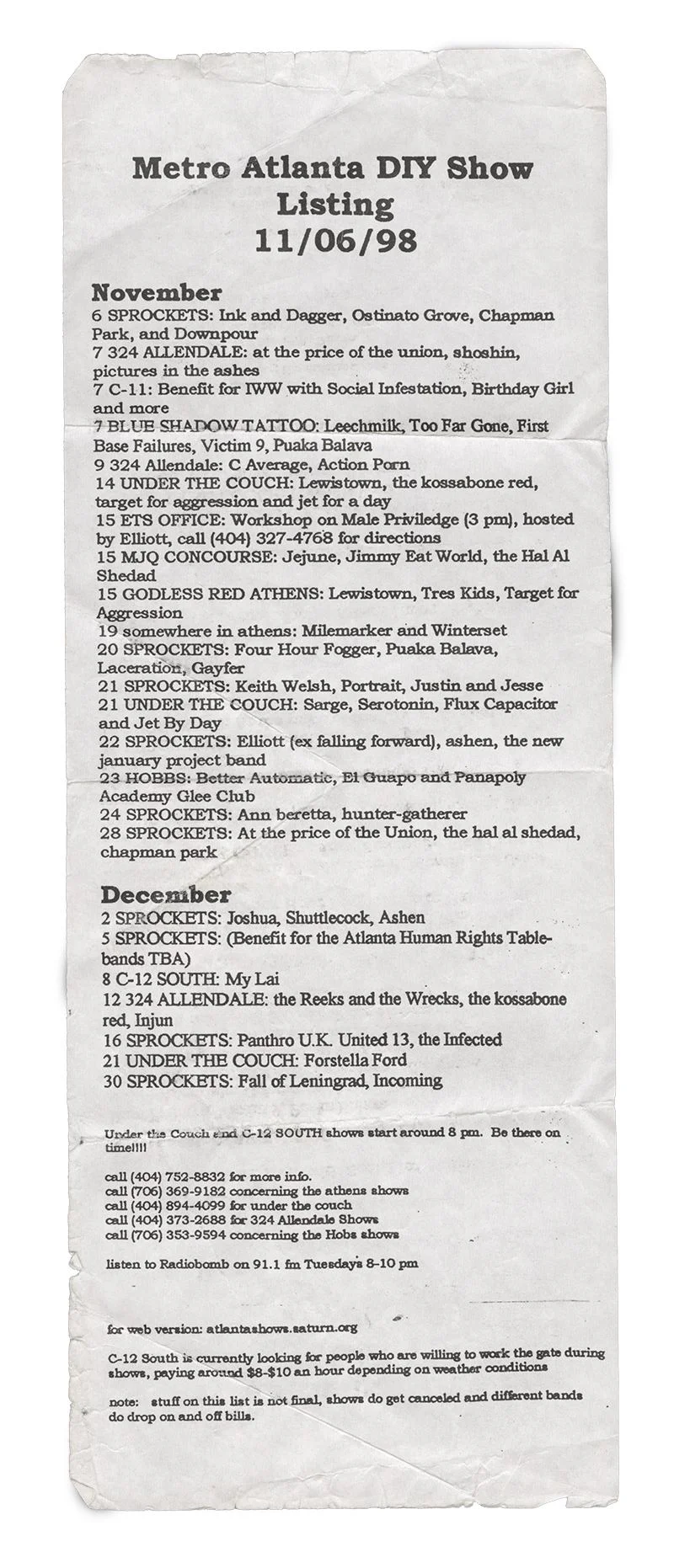

In the library of Atlanta’s august Emory University, there now sits a new collection of punk-rock memorabilia — alongside original manuscripts by the likes of Alice Walker and William Butler Yeats. This photo essay offers a peek at the collection — and the first collaboration between The Bitter Southerner and ArtsATL.com, a website that’s been our home city’s best source of arts coverage since 2009. ArtsATL today is publishing a great piece — written by Steven Grubbs — about the Emory’s Atlanta Punk Rock Collection. The Bitter Southerner is happy to bring you a broad selection of photos and archival materials in conjunction with the project, plus a few words from our editor, Chuck Reece, about how and why punk rock captivated young Southerners of the 1980s and ’90s.

It’s shocking to reach the age when the artifacts of your youth enter the collections of libraries and museums, displayed behind glass to teach younger generations about what came before.

The first reaction is expected: “God, I’m old.”

The second reaction feels better and more hopeful: “Maybe that crazy stuff we did actually mattered."

To walk into the Emory University Library right now is to confront the legacy of a thing called punk rock — a force that changed many young Southerners (all over the world, for that matter) in the 1980s and ’90s. And punk's ethos continues to do so.

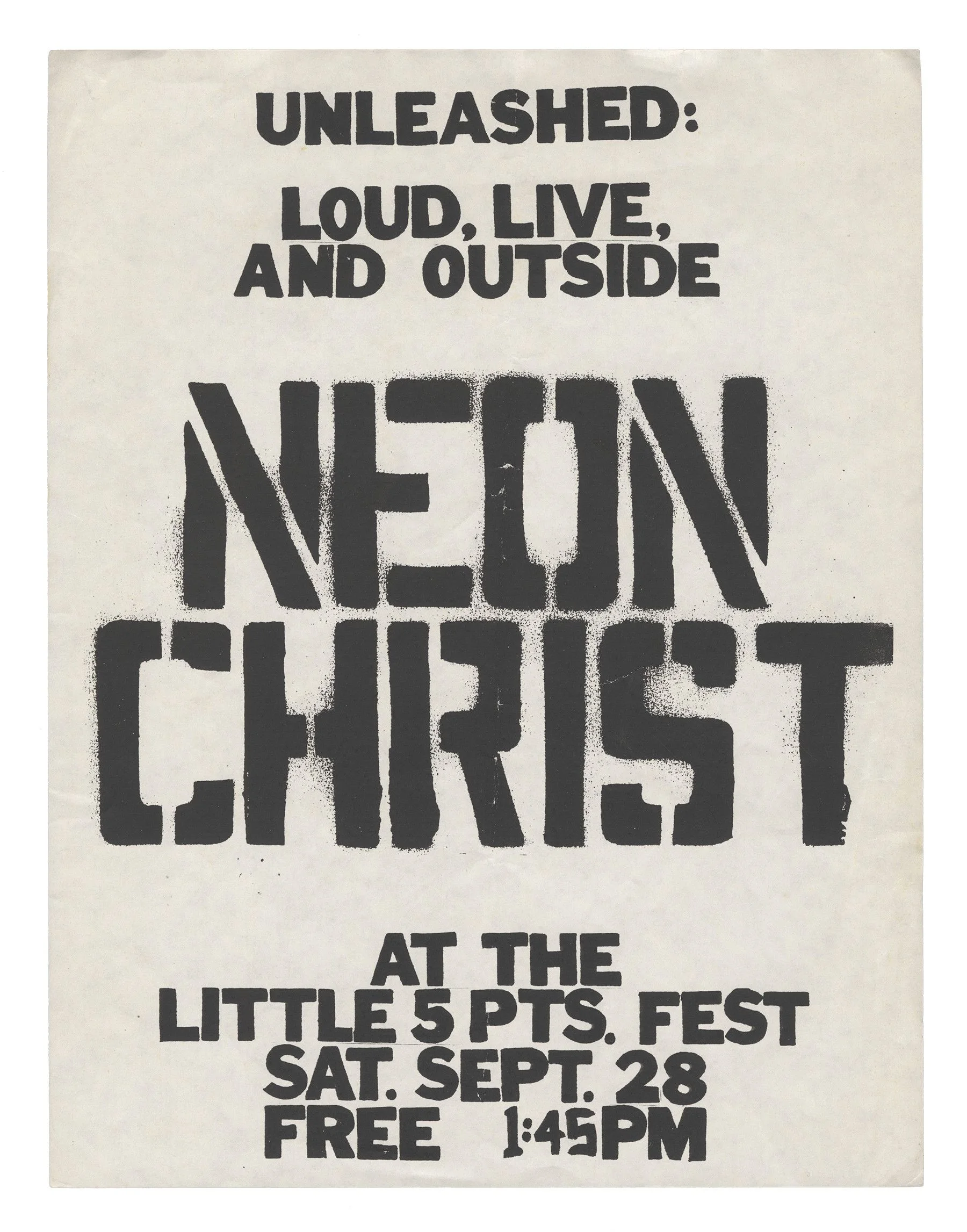

Randy Gue, now the curator of modern political and historical collections at Emory, was one of those young punks. He ran with Neon Christ, one of the bands that anchored Atlanta’s 1980s punk scene. He tells ArtsATL today, “I was born to my family, but I was raised by my friends, and my friends were in Neon Christ. And that shaped who I am and what I do.”

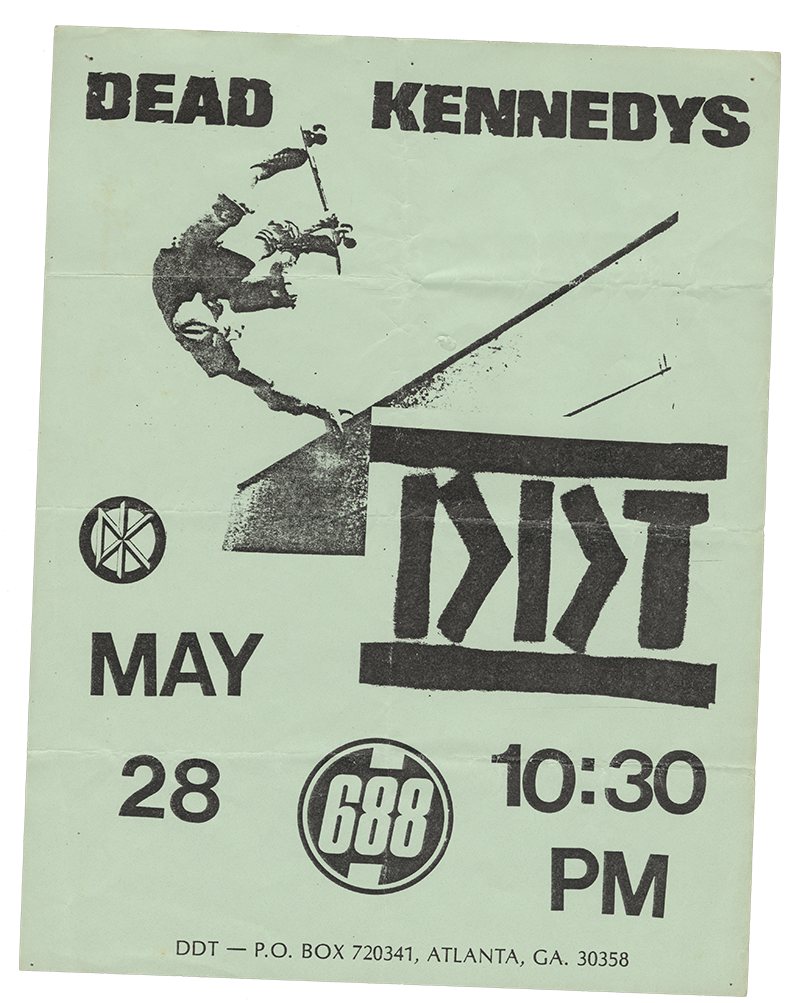

Punk’s spirit of free interchange and mutual support brought young Southerners into a network of scenes all over the country. It exposed us to worlds (and opportunities) far broader than we had known growing up down here. One night in 1984 at the long-gone Atlanta punk club 688, I saw the first Atlanta performance by the Minutemen, a groundbreaking band from San Pedro, a town of longshoremen south of Los Angeles. After watching them play music the likes of which I’d never heard, I went out the back door of the club to tell the guys in the band how their performance had affected me. I chatted with the band’s guitar player and primary vocalist, D. Boon (the D stood for Dennes, but to punks everywhere, he was just D).

“Where y’all playing tomorrow?” I asked.

“Charlotte,” Boon answered.

“That’s a long drive,” I said. “You leaving tonight?”

“Not if we can find a place to sleep here,” he said.

Thus, the Minutemen became my houseguests for the evening: the punk ethic at work. Late that year, I moved to New York City for the first time and wound up taking in the Minutemen and an Athens band, the Kilkenny Cats, on the same night in 1985. Two bands’ worth of gear and about a dozen people squeezed into my tiny, fifth-floor walkup — about 320 square feet.

About a week before Christmas in 1985, I visited L.A. I called D. Boon at home. He invited me to drive down to San Pedro for a visit. We sat in the living room of his small home, listening to a cassette tape of “3-Way Tie (for Last),” the new Minutemen album, which was about to be released. He showed me the painting he’d done for the album’s cover. I remember him apologizing several times for stepping out to load suitcases into the band’s van. He told me he and his girlfriend were about to leave for Arizona to visit her family for the holidays.

D. Boon died on the way to Arizona — not the victim of rock and roll excess, but a garden-variety car wreck. He was catching some sleep in the back seat when his girlfriend lost control of the van. He was thrown out the back door and killed instantly, his neck broken.

He was only 27 years old when he got tossed off this mortal coil, but our brief friendship stays with me. It’s just one example of how kids in the South came to know other kids like us from all over the nation, thanks to punk rock. We learned about each other's roots and motivations. We shared common joy in a maelstrom of electric guitars and common anger at an increasingly ludicrous power structure. And, if I may paraphrase Emory curator Gue, we raised each other. The collection Gue has assembled proves the truth in the words D. Boon wrote a couple of years before he died: “Our band could be your life.”

— C.R.

“I lived in Gwinnett, so I would see flyers for Act Of Faith shows and Crisis Under Control shows, but I always thought, ‘Ah, I can’t go to that. Some skinhead will punch me in the face.’ So my first concert ever was Metallica at the Omni, and I was literally up on the very last row, and I had no connection to the band whatsoever. It was like, ‘What do I even do? Do I air-drum up here?’

“But some guys I would skate with had given me Act Of Faith and Crisis Under Control tapes, so I knew those guys, and the next concert I went to was GBH with both those bands at The Masquerade. And during Crisis Under Control all these fights kept breaking out — any show I went to for like the first five years was just so many fights all the time — and Rob from Act Of Faith got on the microphone and tried to get everybody to stop, which confused me because it was my first show and I thought that was just what you did at punk shows. When me and my brother left the show, a massive brawl happened right in front of The Masquerade, and it was all these skinheads versus the Atlanta hardcore guys -- guys I eventually became good friends with. It looked like 'The Outsiders,' two walls of people running into each other. And I was just standing there watching it. I must have been like 13 or 14. But it didn’t deter me. I feel like I went to every Act Of Faith show after that.”

Atlanta punk rock collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

“When I was in fifth grade there was this guy that lived in Duluth—after Neon Christ and everything, that was where it started again, in Duluth—and he had an older brother who turned out to be involved in hardcore, and who had given him a mixtape that he passed along to me. And that—along with skateboarding and seeing bands and their t-shirts in Thrasher Magazine—really got me more into the punk thing.

But, yeah, then bands started out in the Duluth area. A guitarist named Jonathan Dixon was in a band called The Crooks and they were playing at a place called Visions in Gwinnett and at The Pit in the West End. That was sometime in ’88. They sounded like fast early hardcore, but also sort of sing-songy and slightly melodic. That was kind of the beginning of it. The Crooks are the branch, and then it became Act Of Faith in ’89. They were the hometown heroes. Jonathan started as Act Of Faith’s guitar player, and then moved over to drums. He’s a police detective here now – narcotics, I think.”

“I mean, if you think about Atlanta in the early ‘90s, Act Of Faith was the band that was the big deal for everybody, so that’s what people had to draw from. But information travels faster now, so your palette is bigger. It’s a lot easier now to pull from things that aren’t just local bands as reference points. That makes it easier to create an artistic persona that doesn’t necessarily represent a lifestyle.

In terms of genre, you’re harder pressed now to find people who are this and therefore make this, because everyone has more styles to pick and choose from. By the middle 2000s, you would have a hardcore band, a street punk band, and a power pop band, at one house show. And it was all very referential.”

Atlanta punk rock collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

“I worked at The Earl, but I was mostly involved in a whole bunch of house shows, really. There was the I Defy, which I was going to around 2004, and then we started a house called I Can Fly, and I think that was 2006 and 2007. After that, there was I Can Fly II, which became known as The Yellow House. Creative Loafing did a thing about that house before it was bulldozed. We [he and Amanda Mills] now do shows at Murmur [their downtown space that serves the DIY community]. From around 2008 to 2010, there was the Wells Street Warehouse, where somebody had rented out a warehouse space and pretty much every punk and hardcore show was out there, for like two years.”

“It is certainly more diverse than used to be, but I’m not going to pretend it’s a huge happy story being a woman in the punk scene...Most of the reason why I’m less involved now than I used to be is because of certain experiences with abuse. It’s certainly not something that is exclusive to punk, but I wish it was talked about more. It’s something I’m very conscious of with putting on shows and having a venue space. Like, how do I run this venue in a feminist way? I actually think that some of the punkest shit that’s happening out there right now is people sitting cross-legged on the floor with a bunch of pedals and their iPhone, and doing really weird shit. There are a lot of women doing that. There’s a new house called DownHouse Collective, and it’s a very feminine punk space. It’s not the scene of four dudes playing guitar and beer slinging, but it still feels very punk and it’s incredibly DIY.”

“I mean, there is still that scene, and it’s huge, but it’s totally separate from us. For Atlanta, there’s Criminal Instinct and Foundation. Foundation is probably the biggest, even though they’re quitting. There are some bands that are bridging the gap between our scene and those bands, though, like PVC, which is one of the guys from Foundation. That’s making a little bit of crossover, but still, not really."

“When I came on board, a lot of our collections died out in the 1970s. It was only, like, dead white men. I wondered how I could put my stamp on the collection, so one goal was expanding the chronology of it -- moving it from the 1970s and into the 21st century -- and then diversifying the holdings, getting it away from just captains of industry and all that. I grew up in the hardcore scene here in Atlanta. It made me who I am. I was born to my family, but I was raised by my friends, and my friends were in Neon Christ, and that shaped who I am and what I do. So, one of the things I now want to do is document DIY culture in Atlanta.

“One of our goals is to provide long-term public access to these things. And by long-term, I don’t mean 50 or 100 years. I mean a thousand years. The person I collect for is some graduate student 150 years from now that wants to find out what the punk scene was like in the mid 1990s. So, I have to think about what they have to have to be able to make those connections. All these scenes and people — y’all know it, but in 20 years all those connections will be gone. What if somebody wants to reconstruct that? What do they need?”

The Rose Library archive at Emory’s Robert W. Woodruff Library is free and open to the public, and it is always accepting relevant donations. To donate materials to the collection, contact Randy Gue at randy.gue@emory.edu. All high-res scans of punk artifacts are courtesy of Emory University.