No building in the South is like the Ryman Auditorium. No other edifice so vividly embodies the history and cultural contributions of its city. Today, writer Jennifer Justus takes us on a journey to find out why the good heart of Nashville lives in the Ryman Auditorium — and how that spirit, for almost 125 years, resisted every effort to dislodge it from its home.

Story by Jennifer Justus | Photographs by Aaron Coury

Musician Marty Stuart remembers sitting on his grandmother’s lap in Mississippi listening to the Grand Ole Opry at the Ryman Auditorium when the musicians paused to memorialize Patsy Cline.

“From 380 miles away,” he recalls, “I could hear people crying.”

As a young player and lover of bluegrass, he also knew that the genre came to be on the Ryman stage. So, at 13, he took a Greyhound bus to Nashville, arriving at nearly 3 a.m. Feeling scared and lost, he rounded the corner from the bus station to face the Ryman for the first time as it cast its red brick and gothic-arched shadow over Broadway.

“It almost drove me to my knees,” he says.

And then about a week later, he had the chance to play on the stage as a guest of Lester Flatt. During that first performance, the crowd gave him an encore.

“I thought I’d done something wrong,” he remembered. He turned to Flatt during the applause and asked: “’What do I do?”

“Play it again,” Flatt said.

All these years later, Stuart can still recollect the smell of popcorn, sweat, hard work and coffee from the pews at the Ryman when it hosted the Opry full-time. He knows he had an early baptism in the magical spirit of the place, and it wasn’t lost on him even as a boy.

As Nashville undergoes a whiplash of change under a web of steel cranes, the Ryman stands sturdy among the neon and glass. Hallowed halls like “the mother church of country music” can’t merely be built like a skyscraper or condo complex after all. They must become — painted with layers of experience and mystery over time. Try to uncover the meaning in their spirit by peeling back the paint, and you’ll only find another color, deeper and richer, worn in.

The Ryman is a physical emblem of the spiritual — a reminder that takes us beyond ourselves. And as former Nashville Mayor Bill Purcell put it, the Ryman reminds us, looking forward, of who we still want to be. Through two renovations — one in 1994 and another last year — the building helps tell the story of this place from the performers who graced the stage to the men and women who built and ran the place. But it also offers a comeback story of Nashville, saving a piece of its soul. Because in the 1990s, after a century of becoming, the old lady Ryman had nearly come to her end.

Long before the Grand Ole Opry made the Ryman its home, her bones had been rattled by years of hellfire preaching, political rallies, livestock shows, opera productions and John Philip Sousa’s tubas. She had heard Louis Armstrong’s trumpet and Mae West’s purr. Then, for 30 years the Ryman hosted the Opry’s “good-natured riot,” drawing visitors to hoot and raise hell of a different sort from the pews.

In the building’s history, major renovations had never been made. No air conditioning. No heat or proper dressing rooms. And after the Ryman lost its main tenant — the Grand Ole Opry — in 1974, even Roy Acuff proclaimed it might as well be torn down. Sitting mostly empty while the Opry headed for cushy new digs that matched the slicker sound of that period, the old revival hall waited on a wrecking ball, offering hardly much more than rinky-dink tours for a couple bucks.

Birds swooped from the inside rafters on occasion. Pews were splintered and stamped with wads of Juicy Fruit. And the stage that held the weight of Hank and Cash felt like it could give way.

Stuart returned during this period as a man — and as a guest rather than a performer. He bought a $2 ticket for the tour and retreated to the balcony to think.

“I felt lost,” he said, and in a different way than when he stumbled on the building as a boy. “I thought it would be good if I went to the Ryman.”

He saw where rain had come through the roof, but he also saw the bones of the place still intact and heard echoes of its glory days.

“Me and this building are about in the same shape right now,” he said to himself. “We could use a renovation.”

In the 1890s, fleets of steamboats whistled and dinged along the banks of Cumberland River. Crews stacked tobacco and cotton along the riverbank as horses clopped past pulling buggies.

As it modernized, Nashville became a major rail hub and river port, which in addition to commerce brought a cast of new characters to town. The population in 1892 was nearly double what it had been a decade earlier, leading to overcrowding and crime. Gambling, prostitution and public drunkenness spilled from the city’s estimated 90 saloons.

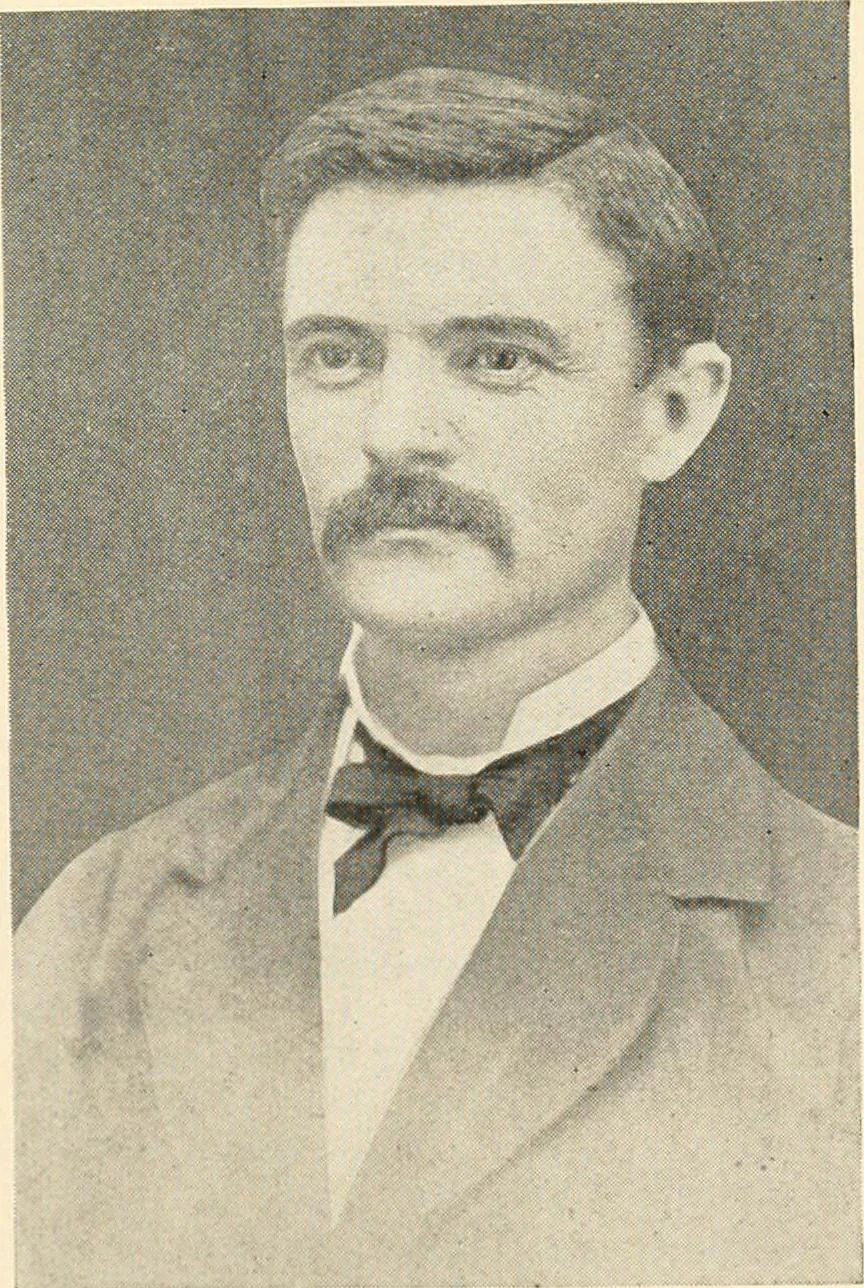

Sam jones, 1922

It seemed a prime target, then, for traveling evangelist Sam Jones, who set up a tent and railed against dancing, gambling and most of all alcohol. The Georgia native struggled with alcoholism until turning his life around at his father’s deathbed, He honed his blunt and down-home preaching style in rural North Georgia. His writings were collected in a book called “Quit Your Meanness.” When he first came to Nashville in March 1885, he drew thousands, connecting with migrants from rural areas while also challenging the affluent who attended the churches downtown.

After his first visit, he sent a message to the naysayers who called him crude: I’m not worried about offending people, he said. I’m worried about not offending people.

“He was a rock star, basically,” says Nashville historian David Ewing.

Meanwhile, Thomas Ryman, a wealthy riverboat captain, kept the saloons on his fleet of 35 steamers well-stocked with booze. If not taking part in the antics on his boats, he could survey them from the wraparound porch of his Queen Anne home on Rutledge Hill.

Though legend says Ryman went to Jones’ tent to raise a ruckus, it’s more likely he just wanted to see what the fuss was about. Either way, when the invitation hymn began, he stood converted, and walked over sawdust to meet the preacher who had convinced him to swear off a life of sin.

Ryman turned out to be one of Jones’ most productive disciples. And he presented Jones with the idea for the Union Gospel Tabernacle, a brick church of Gothic design, where all Nashvillians would be welcome regardless of background or denomination. Jones and other preachers could spread the Word under a wide roof with stellar acoustics.

Completed in 1892, the project racked up debt that Ryman would spend the rest of his life trying to repay. And though he intended it for religious purposes only, it soon became a public hall run by a group of local businessmen.

Helping bridge the gap — or some might say the fine line — between the spiritual and secular, the Fisk Jubilee singers performed spirituals on many occasions. Local churches rented the space, such as the General Conference of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, which brought in Booker T. Washington. Colleges held graduations. Educational speakers talked on philosophy. And by 1901, the Philharmonic Society of Nashville invited New York’s Metropolitan Opera for a show. The Met’s company performed the French composer George Bizet’s “Carmen” at the church.

The Met’s visit didn’t pay off the debt, as the operators had hoped, but it led to construction of a proper stage, and it changed the course of cultural history in Nashville. Opera stars and internationally recognized violinists, pianists and dancers, such as Isadora Duncan, followed.

After Thomas Ryman’s death in 1904, the auditorium was renamed for him. Now a venue for all types of performers and speakers, it drew audiences just as varied as those who graced the stage.

The Ryman, however, needed a woman’s touch. And it came with Lula C. Naff, “the high priestess of the Tabernacle.” She took over the Ryman’s operations before women could even vote, and she ran the operation for more than four decades.

Shrewd and fearless, she avoided tipping others off to her gender by signing her name “L.C.” But she did change the course of culture in Nashville. She added credence to its highbrow “Athens of the South” nickname, which was bestowed on the city in the mid-1800s, while also paving the way for the country music connections in the days to come.

“I think she was super-smart and driven,” says Sally Williams, the current general manager of the Ryman and only the third woman to manage it in its 125-year history. “The courage she had to have. She would go to New York and meet with the agents and managers and artists. Nashville was not a huge place on the map at that point. To get (Enrico) Caruso and (Sarah) Bernhardt — I think that was very important from a cultural perspective for the city.”

Williams relishes the opportunity to carry on her legacy. “Take it out of the Ryman,” she says, “and Lula’s story is still amazing.”

Indeed, Naff had moved to Nashville as a widow with just her young daughter. She worked as a secretary for DeLong Rice Lyceum Bureau, a company that booked speakers at the auditorium. After the company dissolved, she boldly leased the Ryman as an independent agent until the board hired her as manager in 1920.

She booked Orson Welles, W.C. Fields, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, President Theodore Roosevelt and Helen Keller, to name just a handful. And she went to court to defend the production of “Tobacco Road,” the stage adaptation of Erskine Caldwell’s 1932 novel, against the Nashville Board of Censors.

While other theaters of the day closed, victims of the Depression and the newer “talkie” pictures, the Ryman thrived under Naff’s leadership and never posted a loss during her tenure. Naff continued pulling in big acts, pounding the pavement to promote shows and sell tickets, even as the building aged. She took in stride the good-natured ribbing — and genuine criticism — for the Ryman’s rustic ways.

Meanwhile, just five years after Naff took over at the Ryman, a company located a block away, National Life and Accident Insurance Company, started a radio station. With call letters WSM, for “We Shield Millions,” it launched a Saturday night show called the Grand Ole Opry that would become the longest-running radio program in history.

So, with the Ryman already 50 years old, the building’s biggest and probably rowdiest tenant had yet to come knocking.

“Welcome to the Ryman Auditorium,” said the country star Vince Gill at one of his Bluegrass Nights shows last June. “My favorite place to play in the whole, wild world. Hands down.”

The light of summer’s early evening sent rays, like the fingers of God, through the Ryman’s jewel-toned arches of stained glass as Gill posted up on stage. He wore faded blue jeans and a black T-shirt with TATER printed across the front, a nod to the nickname Hank Williams Sr. gave to Little Jimmy Dickens. And with just the organic wooden sounds of mandolin, banjo, fiddle, guitar and a doghouse bass, Gill and company lit into “East Virginia Blues No. 1,” and took that crowd back to church.

That night at the Ryman conjured the old Opry vibe. For one, the show drew a varied and sold-out crowd in hippie skirts and do-rags, cowboy boots and khakis with polos. Eddie Stubbs, respected WSM announcer, kicked off the night of bluegrass with a spokeswoman from Springer Mountain Chicken, the show’s sponsor, which had helped keep ticket prices for the Bluegrass Nights series some of the lowest of the year. And the commentary seemed as straightforward as the musical styles: “If y’all will go out and buy our chicken, we’ll come back and do it again,” she said.

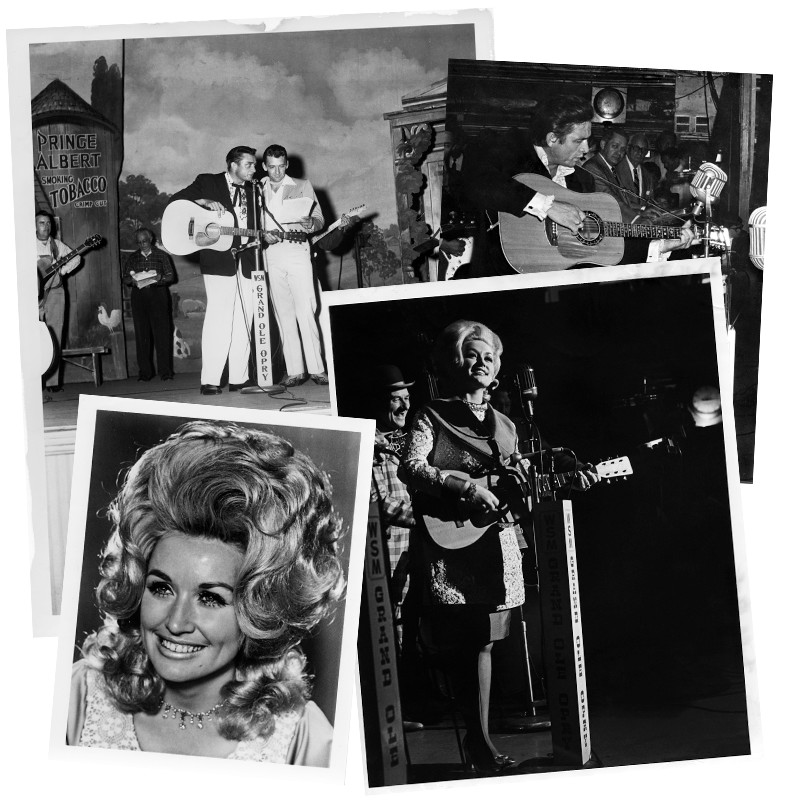

Even though Vince Gill didn’t become “Vince Gill” as a bluegrass artist, he has loved the genre since his teen years. He plays the Bluegrass Nights series each year. Bluegrass, after all, came into being on the Ryman stage (and “probably some dressing rooms,” says Ricky Skaggs) when Bill Monroe, Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt played together in 1945.

Like the country music that founded the Opry, bluegrass is the music of both sorrow and struggle, optimism and family. And with Gill leading the band through gospel numbers like “Drifting Too Far From the Shore” and then the rousing “Big Spike Hammer” by the Osborne Brothers, the mood of the room shifted, too, from pin-drop quiet to whooping and jovial. It wasn’t a stretch to imagine hand-fans stirring the humid air over Opry guests.

But it’s a common misconception to think the Opry began at the Ryman. It was, in fact, the show’s fifth home. The Opry sprung from the hallways of the first floor of the National Life building. The company then built a 500-person auditorium, which it quickly outgrew.

After a stint at the Hillsboro Theatre (now the Belcourt Theatre) in 1934, the Opry’s following grew so large and passionate, it had trouble keeping a home.

“It was not the symphony-going crowd,” says the historian Ewing.

Booted from the Dixie Tabernacle due to complaints from neighbors in toney East Nashville at the time, it moved to the War Memorial Auditorium downtown, only to be kicked out of that hall, too, in 1943.

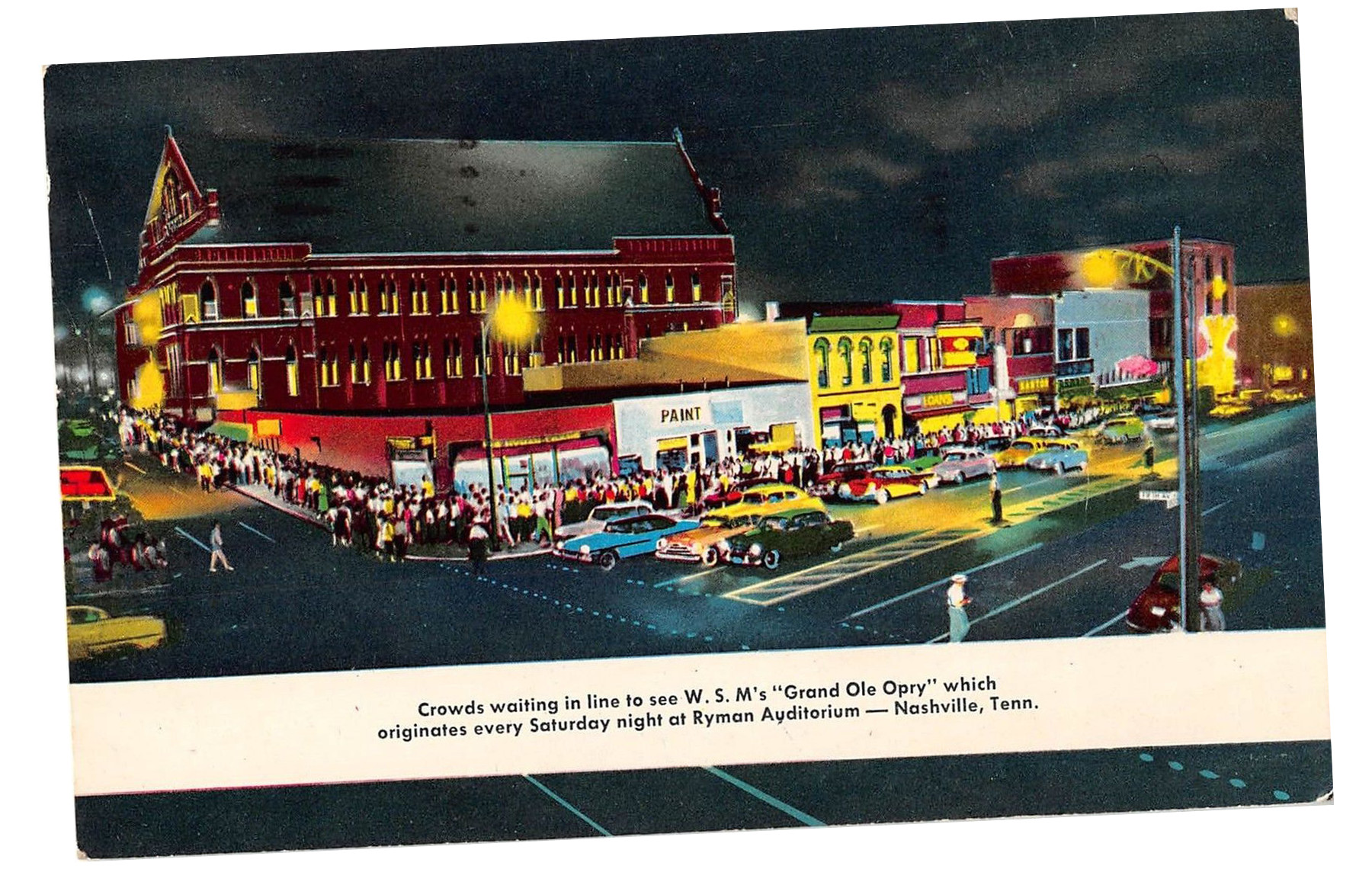

“The Ryman had a little age on it,” Williams says. “So, having some hillbillies in here having a good time? It was no big deal.” The well-worn Ryman and Opry made for a perfect marriage that helped establish Nashville as the country music capital of the world.

“What a big time that must have been,” Williams says of the lines of people wrapping around the Ryman, waiting hours for tickets. “I envision it as really hard-working people coming together on the weekend to have a great time. So, yeah, I bet they were rowdy. That said, some of my favorite photos of that time were the little kids sprawled out on the pews sleeping. It had probably been a long day for them.”

Williams also says creating a home for the show made the Ryman an important part of the Opry’s history — as well as country music’s.

“There is no other genre that has a home,” she said. “This amazing institution (the Opry) can connect the dots from then to now, and then the Ryman, in which you could actually experience it.”

With the windows thrown open on Saturday nights, World War II soldiers traveling through town, staying at the YMCA or even sleeping on a park bench nearby, could hear “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” or “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (With Anyone Else but Me).”

By 1945, Decca Records sent a producer to town, giving country music a stamp of validation from New York, and later, RCA Victor opened in Nashville. The legendary record producer Owen Bradley, who had worked at WSM as a musician and program director, bought a home that would become the first studio on Music Row.

By 1956, the Opry cast added Johnny Cash, and he met June Carter for the first time backstage. The Opry cut ties with Cash after he smashed out the footlights with a mic stand. But in 1969, he returned to the Ryman to film ABC’s “The Johnny Cash Show,” insisting that it happen at the old church.

©Grand ole opry, LLC

“I think those (shows) were really important for the city,” Williams says. “The Ryman via ‘The Johnny Cash Show’ brought Dylan and Eric Clapton and all of these great people who weren’t familiar with Nashville and what we all know is the infrastructure that supports music here, from the studios to the writers and the musicians. The Ryman was pivotal in that piece — opening the door for more people to come here.”

But as the years and crowds continued to put a beating on the Ryman — and the country music sound became more countrypolitan — the Opry decided to move to a new facility away from an increasingly seedy downtown. The new Opry house would have comfortable seats, proper dressing rooms and central heat and air. And with those amenities, the Opry’s exit from the Ryman in 1974 couldn’t have been easy to mourn.

As Nashville residents and businesses fled to the suburbs in the 1970s and ’80s, downtown Nashville felt patched together, replete with pawnshops, adult peep shows and pool halls. Though it may draw hundreds of thousands on New Year’s Eve today, photos from that night during earlier eras look as though the rapture had just happened.

National Life, which had purchased the Ryman in the 1960s, commissioned a New York theater design expert to conduct an assessment of the building: “It would be unprofessional for me,” the assessor wrote, “to recommend the preservation or the reconstruction of the Ryman.”

But what could have been the final straw for the Ryman launched a debate among historic preservationists. That debate ended up buying the building some time. Then, by 1983, Gaylord Broadcasting Company had purchased the Ryman as well as WSM radio, the Opryland Hotel, the Grand Ole Opry and Opryland USA theme park.

Still, Gaylord wasn’t sure what to do with the building.

Downtown began to show signs of new life when the Nashville Convention Center was built next door to the Ryman in 1987. But the building intentionally lacked doors that would send guests onto the main drag of Broadway

So, when Tennessee House Majority Leader (and future Nashville Mayor) Bill Purcell approached the Ryman owners in 1991 about holding a fundraiser at the auditorium, they did their best to talk him out of it.

“In the end, to my enduring delight,” Purcell says today, “they were open to trying this one event — if I would get additional insurance.”

Tom Lee, a Nashville lobbyist who attended the fundraiser, remembers having to sign a safety waiver.

“It was shadowy and a little scary,” Lee says. “But it was magic. There was a sense of all these dislocated spirits around that hadn’t been put back in place. You were in this magical house, and everything was out of order.”

A few other private events were held during the era, including the wedding of Bill Lloyd of the band Foster & Lloyd in 1990. And he remembers a blue tarp draped over the roof at the time. (Lloyd later named him son Ryman.)

A key turning point in the Ryman’s history came in 1991, when Emmylou Harris held a three-night stand at the venue for just about 600 guests. She recorded and filmed the performance and named it “At the Ryman.”

“Is it wonderful to sit out there?” she’s heard asking the audience in her sweet soprano. “Is this a great place to feel the hillbilly dust?”

Steve Buchanan, executive vice president of Ryman Hospitality, remembers an event Gaylord held to commemorate the Ryman’s centennial in May 1992. The company commissioned a one-man play interspersed with performances by artists such as Connie Smith, Vince Gill, Ricky Skaggs, Bill Monroe and Emmylou Harris. About 600 people were invited.

“I think it sort of brought back a lot of memories for people,” Buchanan says. “And for people who hadn’t been in the Ryman for a performance, it showed what an amazing place it is.”

So, in 1992, Gaylord decided to invest in the Ryman — and downtown — by pouring $8 million into a building that had been constructed a century earlier for $100,000. Buchanan, who was promoted from marketing to general manager in 1993 to oversee the renovation, says they focused on how to make the space one that met contemporary standards and expectations while trying to ensure it had that same character and personality. They conducted historical paint studies and recreated light fixtures from the turn of the 20th century.

Marty Stuart visited again during this period, sneaking in among the scaffolding to share a private moment with Connie Smith, the respected country singer and Opry member who would also become his wife.

“I remember holding Connie’s hand,” he said. “We went from the bottom of the dirt all the way to the tiptop of the attic together. It was great to just explore with her. We were just courting at that time. This place was coming back to life. And to watch it come together, it inspired us.”

With the renovation complete, Stuart, in a more official capacity, also helped cut the ribbon.

“The re-opening of the Ryman really paved the way for what is happening down here,” Williams says.

Garrison Keillor, who had been inspired to create “Prairie Home Companion” after a trip to the Ryman in the 1970s, held a live broadcast as the renovated Ryman’s debut performance in 1994. He returned last year as well, calling up that early vibe that inspired him:

And the music came pouring out the windows

Old foursquare gospel harmony.

The music arose and put its arms around you.

Like family. Like family.

Indeed, from patron to performer, those who talk of the Ryman tend to invoke the spiritual.

“One of the things I love about this building is I believe it is ground zero for the spiritual part of Nashville — not just the musical part of Nashville,” Ricky Skaggs says. “Because this was and still is a church — the Union Gospel Tabernacle. They can change the name … the intent for this building, its purpose, has never changed.”

When Stuart talks about the Ryman, he straight-up quotes scripture — Ezekiel 37 — about finding life in the valley of dry bones.

Musicians seem intent to call up those spirits and are sometimes overtaken by them. Williams, who tries to catch at least part of every performance, has seen artists kiss the stage or weep. They often ignore their own setlists when the spirit moves them. They blurt out stories they probably never planned to tell like when Band of Horses singer Ben Bridwell revealed the gender of his unborn baby girl when he received a note mid-set.

“It’s amazing what this building does,” Williams says. “They know they’re playing where heroes have played. They also can’t fake it, partly due to the close proximity. That creates a huge responsibility for an artist. There’s no masking here.”

Roy Agee, a Middle Tennessee native and trombone player, says he didn’t think much of the Ryman before he played it. He remembered his grandmother talking about the building, but he took its history for granted. That all change after he stepped on stage for the first time with Steve Cropper of Booker T. & the MG’s.

“There’s some kind of spiritual element to it,” he says. “You can feel the energy … the spirits that dwell all inside the building.”

Naturally that feeling is passed on to the pews.

Even those who don’t know a lick of history about this place find it impossible to escape the invisible hands of those honest and sacred spirits.

After visiting the Ryman for the first time on a tour, Jonathan Yoder, 32, of Philadelphia became obsessed with seeing a show. He called the ticket office and scalping sites every day on his vacation until two tickets popped up.

“I’m in the balcony, and she’s downstairs,” he said of his partner just before the Bluegrass Nights show. “It doesn’t matter. It was just one of the things I wanted so badly.”

And locals who regularly attend shows at the Ryman know to anticipate something special with each visit. Even though they might expect the spirits to make their presence known, it’s still a surprise when they do.

That’s part of why the most recent Ryman renovation, completed in June 2015 with a $14 million expansion, didn’t touch the main auditorium. The curved pews of the balcony seem to envelop the stage at the Ryman — especially from a performer’s point of view. And with the house lights up, eye contact seems possible with all 2,362 people in a sold-out room.

A group gathered on that stage over summer to hear details of the $14 million additions. The entrance and exit areas were expanded. Bars were added and shifted, ticket counters moved, and a larger gift shop and new café constructed.

Though Ricky Skaggs and Charles Esten, the actor who plays Deacon on the ABC drama “Nashville,” as well as several executives from the Ryman Hospitality, the first to step to the pulpit was general manager Williams.

She initially had dreams of writing for Rolling Stone, but stumbled into a job her freshman year at the University of Missouri that led her to promoting shows on campus. A few moves and jobs later, and she ended up in Nashville, where over the past year she brought a diverse collection to the Ryman, including Loretta Lynn, Beck, the Foo Fighters and Dave Chapelle.

“I think as many people as possible should have the privilege of experiencing an event here,” Williams says. “In order to achieve that, we have to have really diverse programming, and that’s very consistent with what was happening when Lula was here.”

An actor now plays Naff in a new multimedia presentation that guests can experience as part of the Ryman tour. And the Ryman lobby pays homage with its new Café Lula.

To start the last half of his set at the Ryman’s Bluegrass Nights last summer, Vince Gill sent the band backstage and sat alone on a stool with a guitar. He told a story about writing a song to grieve. And then his tenor pierced the air, which hung thick with history, as he sang his 1995 hit, “Go Rest High on That Mountain.” The same tune had brought tears to every eye — even Gill’s — when he played it at the Opry house two years earlier at the funeral of country great George Jones.

Not wanting to end on a somber note, Gill called the band back out to close the night.

“Let’s send you home tapping your toes,” he said. They finished with a few more church-going numbers, and the band launched into “All Prayed Up.”

As the show ended, the crowd indeed whooped and tapped toes. And it did feel like church — both the somber parts and the celebratory ones. Good music in a hallowed place can leave us feeling uplifted, maybe even ready to be better versions of ourselves. But trying to explain how that feeling comes over a person is like explaining religion — a human attempt to make sense of the divine.

Maybe we’re not supposed to completely understand that feeling at the Ryman. Maybe we’re just supposed to sit in her pews, thankful she’s still here and letting the spirit swirl through the place, to fill us up.

~~~

Jennifer Justus is a Nashville-based writer and author of "Nashville Eats," published last fall. She co-founded Dirty Pages, a recipe storytelling project that’s on display at the Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans.

~~~

This story is dedicated to the memory of the great songwriter Guy Clark, whose tunes graced this building on many occasions.