Wants to Complicate Your Meal

Story by Chuck Reece Photography and video by Tamara Reynolds

The remains of whole hog barbecue, the Lamar Lounge, Oxford, Miss.

Part 1:

“I'm Gonna Eat at the Welcome Table One of These Days”

John T. Edge is talking to me about rice.

Rice, I’m thinking. How much do I need to know? Add one cup of the stuff to two cups cold water, throw in a little butter or olive oil and a little salt, bring it to a boil, stir it, crank it down to a simmer, cover it, leave it for 12 minutes and voila! A pile of little starchy cereal grains. Goes well under just about anything. Rice soaks up gravy real good.

That’s about it, right?

No. It’s not. I’ve watched thousands of hours of cooking shows, and I’ve never heard anyone speak with such conviction about rice. John T. Edge is on the edge of his chair because, by God, I will know more about rice before he’s through with me.

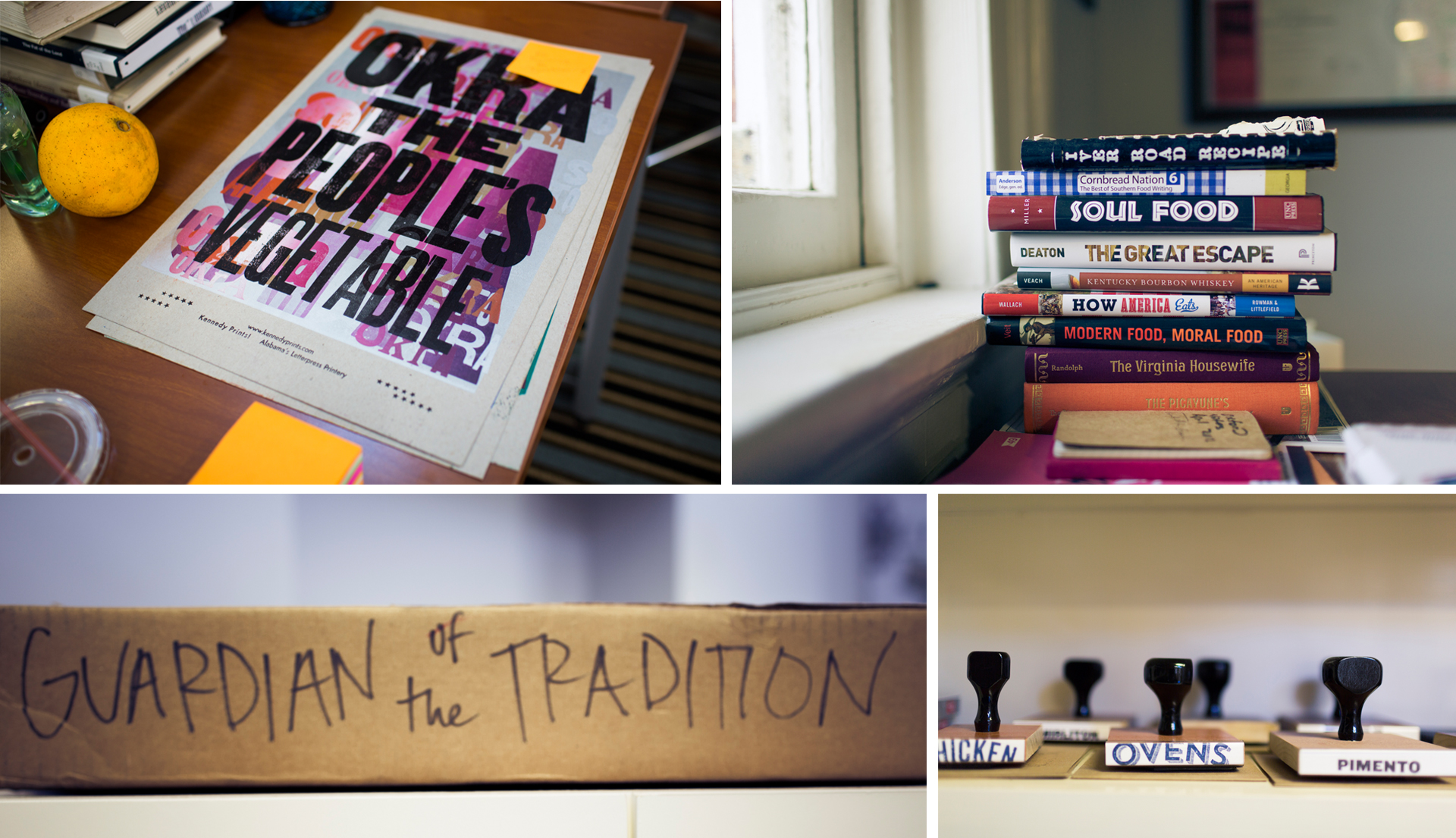

This is happening in Oxford, Miss., in Edge’s office in the Barnard Observatory on the campus of the University of Mississippi. The small headquarters of the Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA), the organization Edge has headed since its founding in 1999, sits in the tip-top of the old observatory, where the telescope was supposed to be but never was, which is a story unto itself.

Frederick A.P. Barnard, a Massachusetts native who later became the president of Columbia University in Manhattan, had come to the University of Mississippi in 1854 as a professor of chemistry and natural history. He believed Ole Miss needed a strong program of study in astronomy. So Ole Miss commissioned the world’s largest telescope and started construction on the building to house it.

The telescope never arrived. It was still under construction when the building was completed in 1859, but with the Civil War looming, a problem arose. Seems the Ole Miss benefactors who’d agreed to finance the observatory had pledged their slave holdings as collateral to cover the investment in the great telescope. Human capital, as it were. Capital that lost its value rapidly when war broke out.

The telescope ended up at Northwestern University in Chicago. Barnard got the hell out of Oxford and went to New York.

The Barnard Observatory (left) and the steps that lead to where its telescope was supposed to go.

Before John T. Edge found his way to Oxford, he’d spent his 20s working at a consulting firm in Atlanta that helped companies (permit us a little corporatespeak here) optimize their human capital. Funny, then, that he wound up here, in an observatory that never got its telescope because of bankers who would have understood the phrase “human capital” to mean something entirely different.

Funnier still that this space now houses the SFA, an organization whose stated mission is diametrically opposed to the values of the slave holders who financed it by using human beings as collateral.

Here’s the mission statement:

“The Southern Foodways Alliance documents, studies and celebrates the diverse food cultures of the changing American South. We set a common table where black and white, rich and poor — all who gather — may consider our history and our future in a spirit of reconciliation.”

The mission hangs me up. It requires an intellectual leap I’m not sure I’m ready to make. So I interrupt John T. (that’s what everybody calls him), and I tell him I’m having a hard time getting from rice to race.

“It’s still a little much for me, honestly, to think that by talking about growing, creating, harvesting and cooking food that we get to reconciliation among the races,” I say.

John T. looks me in the eye and tells me, “And I think you’re too focused on the food. You’re too literal-minded.”

OK, big boy. Explain it to me.

“You know, food is just the way we get there,” he says. “Food on the table is a catalytic converter: reaching for the country ham and talking about the Appalachian roots of your grandfather, or reaching for the okra and talking about the African roots of this whole place. Those foods are facilitators of dialogue and touchstones of culture. They’re just a way to get you into the conversation.”

He’s rolling now.

“We’re not just talking about what we grow and what we serve,” he says. “To talk about food in the South is to talk about labor, who cooks it, who raises the crops. You talk about the expertise of the enslaved Africans brought into the lowcountry of South Carolina, who were valued for their knowledge of rice culture. They were higher valued slaves because they knew how to raise rice. That’s why they were brought in from western Africa. So you serve rice, and you talk about the labor of Africans who made the wealth of the rice culture of the 18th and 19th century in South Carolina possible. You can also talk about 21st century issues around the immigrant labor that picks our vegetables. So I don’t think it’s the food. It’s the possibility that the table offers us to tell stories about and come to terms with our past and our present. That’s different than saying, ‘Let’s just talk about food.’”

I’m beginning to get it. I think back on my own experiences and it’s pretty clear: What happens at the table is different from what happens everywhere else. Talk about race and class in a lot of places, and somebody’ll wind up calling somebody else an asshole, and the whole thing will go sideways.

But when you put people at the table, things get different. Maybe put some country ham, the product of Southern Appalachian folks trying to figure out a way to preserve pork over the winter by salting and smoking it, on that table. Put some fried okra, a vegetable brought to these shores by enslaved Africans, on there, too. And of course some rice, which John T. has already told you about, with some Hoppin’ John on it. Over that food, across that table, we are less likely to accuse and more likely to talk. More likely to understand each other. More likely to reconcile our differences.

And the more we know about the meaning bound up in the food, the better the conversation will go.

“My job is to complicate your understanding of rice. It’s to complicate your Hoppin’ John,” John T. says. “That’s my job.”

He does it very, very well.

Photographer Tamara Reynolds and I got hungry during our drive down to Oxford in early December. So we texted John T. and asked for a suggestion for a lunch stop. I figured if you’re gonna ask somebody for a lunch recommendation in the South, then who better than the guy who runs the Southern Foodways Alliance?

He sent us to Johnnie's Drive-In, a little burger joint in Tupelo, Miss., for something called a “dough burger.” Elvis Presley ate there all the time when he was growing up. His favorite booth has been turned into a shrine of Elvisiana. Road-trippers love to stumble upon places like Johnnie's. It’s pure Americana, a cultural object in and of itself, a perfect example of the roadside burger joint that thrived in the pre-McDonald’s days. We even met a couple of older ladies, fresh from the beauty parlor, one of whom said she went to high school with Elvis.

For most travelers, the kitsch value would be reward enough for a detour to Johnnie’s. But John T. hadn’t just told us to go to Johnnie’s. He had texted back, “Johnnie’s in Tupelo for dough burgers.”

I’d never heard of such a thing, but after a very nice waitress explained it us, we ordered dough burgers. A dough burger contains about a 50-50 ratio (or maybe a little less) of ground beef to smashed-up white bread. When it arrives, we see a burger that's kind of off-white looking, sitting on a bed of sliced onions and mustard on a bun. It tasted … well … good enough. I felt like I should have ordered the all-meat, or “AM,” burger.

I wondered why anyone would come up with such a thing, then it hit me: because it’s all the people who invented it could afford. If you have only a half-pound of ground beef and need to feed a family of six, dough burgers are the answer. Put enough mustard and onions on them and they’ll taste OK, and everybody gets to go to bed full.

The dough burger tells the story of impoverished Mississippians trying to get by in the middle of the 20th century. It’s not a little slice of heaven in your mouth, but it is a little slice of Southern history. Maybe even Southern present. It is, after all, reasonable to expect that in Tupelo, where the U.S. Census Bureau says the poverty rate is higher than 22 percent, a fair number of people order the dough burger simply because they can’t afford the “AM.” Maybe in Tupelo, a few dimes still matter.

John T. had sent us to Johnnie’s neither to sit in the Elvis Booth nor to taste something delicious. He had sent us there to teach us a lesson.

Sneaky bastard. He’d complicated my hamburger.

John T. Edge grew up in Clinton, Ga., a small community 12 miles northeast of Macon on the road to Athens, a place known mostly for being the home of Old Clinton Bar-B-Q, a barbecue joint that dates back to the late 1950s. John T. and his family lived just down the road, and he remembers countless childhood meals there.

“I took a lot of my meals at the Old Clinton B-B-Q,” he says. “Or we’d go on the way to school and I’d stop with my father at Krystal and sit up on a stool and watch people fry eggs. I was always fascinated with grill cooks.”

After he grew up and moved to Atlanta, he and a friend religiously read Knife & Fork, longtime food critic Christiane Lauterbach’s enduring and insightful newsletter about the Atlanta restaurant scene. They often spent two-hour lunches at whatever new place Lauterbach was praising at the moment.

“Back when I was a corporate swine boy, my friend Greg Coleson and I used to laugh and say, ‘Work is what we do before and after lunch,’” Edge says. “I had a long and strong interest in food.”

That interest in food, however, didn’t drive him to quit the corporate job in 1995, move to Oxford and sign up for classes at Ole Miss’ Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

In his consulting work, John T. says, “we helped people do reengineering work, to figure out what it was they really wanted to do in life, what a company’s real purpose was,” he says. “But I realized my purpose was not there or in any other sort of corporate job. I had a good little life. But there was a huge disconnect between my Saturday night and my Monday morning.”

John T. had been born in the home of Confederate Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson Jr. There was a big Civil War historical marker out by the driveway. His mother was immensely proud to live in such a landmark, but what John T. saw unfolding between the races in the late 1960s and early 1970s had left him feeling distinctly conflicted about his childhood home — a feeling that never really left him.

So at age 32, he decided it was time to deal with that conflict. He took advantage of the real-estate boom that washed over Atlanta as the 1996 Olympics approached and sold his house.

“I was single,” he says. “I could take a chance. I could fuck up. And if it didn’t work out, I could come back to the corporate world with an advanced degree under my belt. I had a real want to understand my region because I love this place and I’m genuinely, viscerally, every damn day of my life pissed off at this place, too. Oxford was the place where I was going to figure that out.”

Nineteen years later, he’s still there, still figuring things out. But now, the whole world is watching him do it.

SFA events draw foodies in locations all over America. Edge’s writing appears regularly in The New York Times, Oxford American and Garden & Gun. He turns up regularly on NPR's “All Things Considered” and countless television news shows. He’s even been a judge on “Iron Chef.” He’s written, co-written and edited scads of books about Southern food. In 2012 he won the MFK Fisher Distinguished Writing Award from the James Beard Foundation.

It seems that no one writes a word about Southern food these days without calling John T. for a comment. He’s become Southern food’s Designated Spokesperson. He is the public face of the SFA. A lot of people think John T. Edge is the Southern Foodways Alliance.

He isn’t. The SFA staff also includes seven women, a couple of grad students and about half of a guy named Joe (more on him next week). And every single one of them will tell you the same thing: that their work isn’t about food. It is, instead, about capturing the stories of the people who grow, harvest, cook and serve the food we eat in the South.

Lindsey Kate Reynolds

Graduate assistant

Joe York

Filmmaker

Melissa Booth Hall

Assistant director

Sara Camp Arnold

Managing editor

Anna Hamilton

Graduate assistant

Amy Evans

Lead oral historian

John T. Edge

Director

Emilie Dayan

Project coordinator

The primary output of the Southern Foodways Alliance is stories. On the SFA’s website are dozens of short films. In its 15 years of existence, the SFA has collected more than 800 oral histories, complete with photographs, of men and women who tend barbecue pits, rake oysters, cure hams, catch fish, grow crops, mill grains and pretty much anybody else who concerns themselves with what our ancestors ate — or what we eat today. The SFA has created what John T. refers to as a “crazy quilt of stories and ideas and pictures and images.”

It’s a quilt you can roll around in for days. Dig into the SFA’s archives on the web, and you might find yourself binge-watching short films or listening to oral histories and looking at pictures for hours. If you grew up in the South, the odds are good you’ll stumble on a story or two about somebody you actually knew from your local barbecue joint or fish shack.

Amy Evans is the SFA’s lead oral historian, and she’s been collecting stories there for 12 years. Sitting in the observatory with her one afternoon, I tell her how John T. had been so determined to complicate my understanding of rice.

“I leave the complicating parts to John T.,” she says, then laughs. “I selfishly just love interacting with the people I get to work with. I’m a conduit for them to share their stories. I’m happy to leave it to other people to connect the dots, to explore the archive and get what they need.”

Amy just likes visiting with folks. “The most amazing thing about doing this work is to have people trust you, to have strangers sit with you for half a day and share their stories,” she says. “I mean, that’s so Southern. Whenever I go do an interview, there’s always food on the table. It is what we’re talking about, but it’s also their gift to me for spending the time. Hopefully, my gift to them is sharing their story and celebrating who they are and what they do. But it’s never lost on me how trusting and friendly and giving people are. When they get to talkin’, you can’t stop ’em.”

Amy and her SFA colleagues do not capture the stories of highly trained chefs from white-tablecloth restaurants, although such people do gravitate toward and support the SFA. If you go to an SFA event, you’ll likely see a gaggle of the South’s most celebrated chefs — people like Birmingham’s Frank Stitt, Athens’ Hugh Acheson, Charleston’s Sean Brock and New Orleans’ Donald Link.

But these star chefs are never the stars of the SFA’s stories. The SFA’s assistant director, Melissa Booth Hall, puts it bluntly: “The people we honor are all blue-collar, all working class.” They are barbecue pitmasters like Rodney Scott, from Hemingway, S.C., and Sam Jones, from Ayden, N.C. They are oyster pickers like A.L. “Unk” Quick from Apalachicola, Fla., or trappers like Pierre Autin from Cut Off, La., down on the Bayou Lafourche south of New Orleans. And hundreds upon hundreds of others, including the man who fed me the first real barbecue I ever ate, the late Bud Holloway of the Pink Pig B-B-Q in Cherry Log, Ga.

One of the SFA’s explicit goals, John T. says, is to put these unsung masters of Southern foodways “on the same pedestal” as iconic chefs such as Stitt or Link. And at SFA events, this actually happens. Barbecue folks like Rodney Scott and Sam Jones work with chefs like Sean Brock to feed the same crowd.

“For me, it’s so crazy,” says Scott, who, until the SFA made a film about him a few years ago, had never cooked outside his family’s barbecue joint in South Carolina. “I can’t get over the amazement of watching these guys preparing plates so pretty, so detailed. But they look at us the same way: ‘They can cook with fire! And they get flavor into this whole animal!’”

And over the common table at these events, black and white, rich and poor just sort of naturally consider their common history and future.

It’s straight out of the SFA mission statement — and its aspirations are not too far removed from the words of a slave-era spiritual:

I’m gonna eat at the welcome table

I’m gonna eat at the welcome table one of these days, hallelujah

I’m gonna eat at the welcome table

Eat at the welcome table one of these days

The SFA’s focus on documenting the lives of working-class people did not arise accidentally. It is quite purposeful, and it traces its roots back to the interests and concerns John T. brought with him to Oxford back in 1995.

“I came here to do race-relations work,” he says. “I wanted to study the Civil Rights Movement. I wanted to study the South’s long history of pitting working-class whites against working-class blacks and watching them beat the ever-loving shit out of each other, which is what wealthy and influential whites have long done. I wanted to make sense of that historically, culturally. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, really. But I just wanted to come here and think about those things and read about those things and write about those things.

“I didn’t come to do food. I found food later.”

Not long after John T. enrolled in the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, it hosted a symposium on Elvis Presley. The center had been founded in 1977 under the direction of William Ferris, who was never known for the being the most conventional academician. The center quickly became known for its oddball programming.

The symposium’s speakers included the Rev. Howard Finster, the legendary Georgia folk artist who repeatedly used Elvis in his images, and the Rev. Will Campbell, the white renegade Baptist preacher from Mississippi who played key roles in the Civil Rights Movement.

“It was greeted with derision by some,” John T. remembers. “It was like, ‘What? You’re gonna study Elvis?’ But to me, that was really emboldening. We were going to think about music as a cultural output. We were going to think about this iconic figure. But to many, that was anathema to the academy.”

John T. the graduate student sat and watched Rev. Finster explain how he dipped his finger in a can of tractor paint and had his life transformed by a vision. “I looked down at my finger and a face come in that paint,” he said. “And it looked up at me and said, ‘Howard, paint sacred art.’”

“Then Will Campbell steps up, the conscience of the South,” John T. remembers. “Will gets up and talks about the term ‘redneck’ and how Elvis was a redneck and how he takes great pride in working-class Southerners and how he takes great pride in the life of his daughter, who was also a redneck and a proud lesbian redneck, and he’s proud of his lesbian redneck daughter.

“I was like, ‘I’m in, man. This is powerful stuff.'”

The Elvis symposium gave John T. ideas. If Elvis could be a way to get people talking about issues of religion and sexuality in the South, then maybe his lingering love of food could also be a lens through which to view the region. He was sitting one night with a classmate who was focusing her graduate work on the history of lynchings in the South. She asked what he was going to focus on. He told her he was thinking about food.

“She said, ‘Grits? You’re interested in grits?’” John T. remembers. “And I kind of got my back up a little bit because I was realizing that I could use food as a lens to look at race, class, gender and all that other stuff.”

He went to the center’s director, Ferris, with an idea. “I wanted to stage a symposium about Southern food culture,” he says. “The center is the kind of place where if you can figure out a way to do something and you’ve got strong interest and show aptitude in your studies, you can do it. I hadn’t seen one done, and I figured if somebody could support a symposium on Elvis, somebody would support a symposium on food culture.” Ferris gave Edge his blessing.

During his time in grad school, John T. had attended the Oxford Conference for the Book and met writers including Jessica Harris, the prolific chronicler of African-American culinary history, and John Egerton, whose work covered everything from Southern food to the Civil Rights Movement. So Edge tried to jump-start his food symposium idea by inviting both Harris and Egerton to speak.

“I was just naive,” he says. “I had no funding at all. But I asked, and they came.”

So did 75 other people, at $195 a ticket. The first symposium on Southern foodways, in May of 1998, was a sellout — a little one, but a sellout nonetheless. And Egerton became convinced Edge was onto something big.

A little more than a year later, on June 16, 1999, Egerton wrote a letter to about 50 people around the South. It began this way:

“As you know, a new effort is emerging to establish an organization that would bring together people from all over the region and beyond who grow, process, prepare, write about, study or organize around the distinctive foods of the South. The principal base for this comprehensive and inclusive group will be in the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. They are offering us an opportunity to use their tax-exempt, non-profit status and their support staff like a greenhouse to grow this new organization, which will have its own officers and board, a self-generated budget, and an independent mission: to preserve and enhance the great food heritage of the South.”

A month later, about 30 of those people gathered in Birmingham. They officially created the Southern Foodways Alliance, elected a board of directors and appointed John T. Edge as its founding director.

John Egerton did more than just write the letter inviting a group together to form the Southern Foodways Alliance. He foresaw the possibilities inherent in creating an organization that would bring black and white Southerners together over the one thing we all have in common: the fact that we eat. If the SFA had a primary source of inspiration, it was Egerton.

From the early 1960s onward, Egerton was something of a crusading journalist in the South, working primarily for The Nashville Tennessean and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Two of his books from the mid-1990s — “Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History” and “Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South” — were hugely influential among those who study Southern history and ponder the region’s future.

Three years after “Speak Now” was published, Egerton summed up his point of view on the South at a Nashville symposium called “Unfinished Business.” Egerton told the crowd: “As black and white Southerners, we have much in our experience that is recognizably similar, if not altogether common to us both, from food to faith, from music and language and social customs to family ties and folklore and spellbinding parables out of the past.”

Egerton was a highly influential standard-bearer for the idea that black and white Southerners could reconcile by studying the things they had in common instead of the forces that kept them apart. And Egerton was the person who opened Edge’s eyes to what he calls “the subversive, activist possibilities of food.”

When I first called Edge in late October of last year about doing this story, he told me I must interview Egerton, that talking to him was necessary to my understanding of the SFA and its work.

But in November, before I could arrange an interview, Egerton died suddenly at age 78.

I drove up to Nashville for Egerton’s memorial service. It was held on a cold Sunday in early December at Nashville’s gorgeous downtown public library. Hundreds turned out, filling the library’s auditorium and a large overflow room where the memorial was broadcast on closed-circuit TV.

Edge was one of four people who eulogized Egerton that day. Edge said:

“By way of his belief in the possibilities of our region, by way of his willingness to speak truth to power — while pouring power a drink and handing power a ham biscuit and promising power a spoonful of homemade lemon curd, too — John Egerton enabled generations of Southerners to do better by our region and by our common man.”

It occurs to me now, after immersing myself in the work of the SFA for weeks, that I probably haven’t heard a statement that better captures the essence of the alliance’s work. The SFA’s job is to help us do better by the South and by our common man ... which requires speaking truth to power ... which in turn is easier to do over a glass of bourbon and a homemade biscuit.

The question before the SFA today is: With its primary source of inspiration gone on, can the organization keep expanding its influence?

Can it truly create the “welcome table” that the old spiritual envisioned?

Next Week :

The Future of the Southern Foodways Alliance

Part 2 of The Bitter Southerner’s series on the SFA will be published next Tuesday.