Wants to Complicate Your Meal

Story by Chuck Reece Photography by Tamara Reynolds and from SFA Oral Histories

The cleavers get a rare rest at The Skylight Inn.

Part 2:

“Unlocking the Rusty Gates”

“Not infrequently, Southern food now unlocks the rusty gates of race and class, age and sex. On such occasions, a place at the table is like a ringside seat at the historical and ongoing drama of life in the region.”

— John Egerton, founder, Southern Foodways Alliance

Four years ago, Southern Foodways Alliance and Southern Documentary Project filmmaker Joe York traveled to Ayden, N.C., about 100 miles east of Raleigh, to make a short film about a barbecue joint called The Skylight Inn. It was not the Skylight’s first brush with fame.

In 1979, National Geographic was working on a book that would be published in 1980 called “Back Roads America, A Portfolio of Her People.” In that book, National Geographic proclaimed the Skylight Inn the “capital of ’cue.” (And yes, that’s why owner Bruce Jones had a capitol dome built on top of the restaurant.) Then, in 2003, the James Beard Foundation gave the Skylight one of its “America’s Classics” awards.

One branch or another of the Jones family has purveyed barbecue in this part of North Carolina’s coastal plain since 1830. The Joneses make their barbecue in the most labor-intensive, time-consuming way: whole hogs and wood fire only. Any Jones in Ayden will tell you that if you break down the hog or use any heat source but hardwood, then it ain’t barbecue.

And there was a time, not too long ago, when the Joneses would have told you that if it ain’t cooked by them right there in Ayden, then it ain’t Skylight barbecue.

But on June 13, 2013, the youngest Jones served the Skylight’s barbecue to thousands of New Yorkers at the south end of Madison Avenue in Manhattan.

How that happened — and the fact that it wasn’t an isolated incident, that it wasn’t a fluke — should give you some clues about what the future of the Southern Foodways Alliance could look like.

Pitmaster James Henry Howell checks his pigs at the Skylight.

About a month after my visit to Oxford, I called SFA director John T. Edge to talk about how he and the rest of the SFA staff were handling the death of their organization's founder and mentor, John Egerton.

Egerton had been an iconic figure not only to the SFA's staff, but also to its more than 1,500 dues-paying members. My December visit to Oxford came only a couple weeks after Egerton’s death, and I’d elected not to bring the topic up. I figured the wound was still too fresh and that everyone on the SFA’s staff, particularly John T., would be at a loss for answers that early, anyway.

When I finally called John T. to address the question, he was still puzzling it out. “I think my own responses will manifest in my writing and my work with the SFA,” he said. “I have this recognition that the very things he set in motion, the questions he asked of me and of the South, that now it’s up to me do my darnedest to answer those questions.”

“Darnedest” isn’t a typical John T. Edge cuss word.

“John was the inspiration for the organization and remained the conscience and spirit of the organization throughout his life,” Edge told me. “And there’s a sense now that … well ... we are the grown-ups in the room.”

The future success of the SFA, it seems to me, depends on how its staff and board of directors define exactly what their responsibilities are — and on how well they carry them out.

In the time I’d spent visiting and studying the SFA, three conclusions became inescapable:

The primary output of the SFA is its ever-expanding crazy quilt of stories. Storytelling is what the SFA does.

The SFA wants to help Southerners — all of us — to knock the chips off our shoulders about where we come from. The SFA’s people do this very purposefully by telling only the stories of working-class, blue-collar Southern food people, in the hope that their stories will raise our region’s and the nation’s respect for them and their work.

The ultimate aim of all the SFA's storytelling is reconciliation among all our region’s races, classes and genders. The SFA lives and dies by the idea that the one place we can truly come together is at the table.

That last one, of course, is the biggie. “When I think about our goal of reconciliation, I try to puzzle through, do we ever accomplish that? Or are we always struggling toward that?” John T. had said back in December in Oxford.

These are legitimate questions. There’s a strong argument to be made that the South remains generations away from genuine and deep reconciliation.

Perhaps the journey itself, as the old proverb goes, is the reward. So I asked John T. to tell me about a specific step or two along the road. I wanted an example of how the SFA and its members took joy in the journey itself.

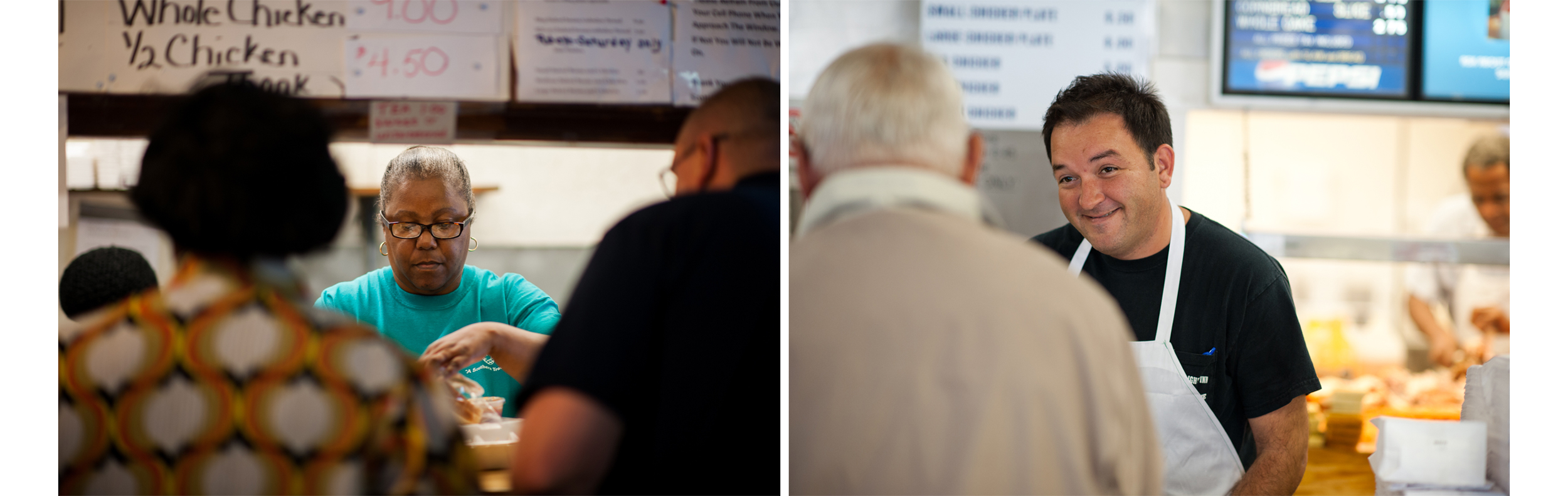

“Well, I think about a friendship that’s developed over the last five years,” John T. said. “It’s a friendship that developed through SFA documentary work. It starts with Rodney Scott, about whom we made a film called ‘Cut/Chop/Cook,’ and Samuel Jones, about whom we made a film called ‘Capitol Q.’ Rodney’s a barbecue pitmaster from Hemingway, S.C., African-American, and Samuel is a barbecue pitmaster from Ayden, N.C., pasty white like me.

Rodney Scott

Samuel Jones

“We have over the last five years told their stories in multiple settings before multiple crowds — everywhere from Napa, Calif., in the front yard of a winery, to events here at the Southern Foodways Symposium,” John T. said. “It’s one thing to tell their stories. It’s another thing to watch the friendship between these two men develop — two men who didn’t know each other but had much in common. Both run multigenerational businesses doing barbecue that is above reproach, just unimpeachable quality. They didn’t know each other, didn’t know what they had in common. The idea that our work, through documentary events, has brought them together … they’re just great friends now. To me, that’s one small step in telling the story of a South that is about black and white marching off together.”

Marching off together in the name of whole-hog barbecue.

Shortly after York finished “Capitol Q,” the SFA asked Samuel Jones, the youngest in the long line of Joneses at the Skylight, to travel to the Charleston Food and Wine Festival to cook his family’s barbecue there.

“Prior to that,” Sam says, “my family had never cooked on location. Man, I thought of every excuse in the world not to do it.”

The year before, York had made "Cut/Chop/Cook" about Rodney Scott, also the youngest in a long line of whole-hog barbecue cooks, in Hemingway, S.C. So some SFA members asked Scott to encourage Jones, to help him overcome his reluctance to travel down to Charleston. After all, the year before, Scott had faced the same experience. Like Jones, he’d never cooked outside Hemingway until the SFA asked him.

So Rodney called Sam and said that if Sam would come to Charleston, then he would, too, to give Sam the help he’d need. That’s how black Rodney and pasty-white Sam, two products of the same tradition who had never met or cooked together before, wound up cooking barbecue together in Charleston.

“He just struck me as a laid-back country boy,” Rodney remembers of his first meeting with Sam in Charleston. “He was nervous. He’d never cooked away from home. But Sam came and we hung out all day. He’s just the funniest guy. He makes me laugh all day with his one-liners. We still see each other quite a bit.”

For his part, Sam felt something he’d never felt before. “Me and Rodney set out cooking that pig at 4 a.m.,” he remembers. “And it blew my mind the appreciation people had for what we do. I mean, when we took the pig off the pit, people applauded.”

Since that festival three years ago, Sam Jones has become a bit … well … addicted to spreading the gospel of barbecue. Three years ago, he tried to find an excuse to avoid cooking his barbecue on the road, but now, he has a trailer rig of his own design, with metal pits big enough for him to cook eight pigs at once.

“Man, I’ve cooked at events from coast to coast,” Sam says. “In 2013, I went from New York to Napa cooking pigs. Rodney and I have become such great friends. We tag-team events, and we literally flip a coin to decide, ‘We gonna do this your style or my style?’ Rodney’ll wear a Skylight Inn cap and serve my barbecue for two days, or I’ll do the same for him.”

Says Rodney: “We respect both families’ ways of cooking barbecue. There’s no competition whatsoever.”

Scott’s and the Skylight, Side-by-Side

Sam marvels at what’s happened to him in the last three years. “If you’d told me five years ago that I’d be cooking barbecue on Madison Avenue, I wouldn’t have just called you a fool,” he says. “I’d have called a library to find out where Madison Avenue was.”

But last June, he and Rodney cooked pigs at the annual Big Apple Barbecue Block Party in Madison Square Park, at the foot of Madison Avenue, smack dab in the middle of Manhattan. They’ll be back this year, and they’ll once again draw thousands of barbecue-crazed New Yorkers who will stand in line for hours to pay $9 a plate for about the only thing you absolutely cannot get in Manhattan: real Southern barbecue.

Sam also marvels at the fact that Rodney traveled 200 miles northward to help cook the pig for Sam’s recent surprise birthday party in Ayden.

“It meant the world to me that he did that,” Sam says. “My birthday was in December, and one of my friends just hounded me about having a shindig out at my shop. And when I pulled up to my shop, Rodney Scott was standing there. Rodney drove all the way from Hemingway, S.C., to be here. That says something. It’s more than just saying, ‘Well, I love you, man. See you next time.’ That’s a real friendship.”

Rodney is a little more succinct: “I’ll be with Sam till the last pig’s off the fire.”

The value and beauty of Rodney and Sam’s story are crystal clear. But what do stories like theirs mean for the rest of us Southerners?

To answer that question when we were in Oxford, we didn’t have to go very far. Specifically, we went to the Lamar Lounge to eat barbecue with Melissa Booth Hall, the SFA’s assistant director, and Sara Camp Arnold, the managing editor of the SFA’s newsletter, “Gravy.”

Let’s start with Melissa. Highly professional, smart, articulate, a lawyer by training. And everything she’s accomplished, she did with a handicap: the fact that she grew up in Kentucky, east of Interstate 75.

West of I-75, Kentuckian thinking goes, is where the more civilized citizens of the state reside. East of the highway is deep, dark mountain Kentucky. Bell County, where Melissa grew up, shares its eastern border with Harlan County. If you’ve listened to even one country song about coal miners (or if you’ve watched “Justified”), you’ve heard of Harlan County. It’s no accident this part of Kentucky inspires its native songwriters to pen tunes with titles like “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive.”

Melissa Booth Hall

"The Saturday before I left for law school, the last thing I did was to ride with my Granny Booth and her best friend, Lois, to Granger County, Tenn., which is where the good tomatoes are," Melissa says. "We left at 6 in the morning. I rode in the back of the truck with my cousin Amanda. We picked five bushels of tomatoes, came home and started putting them up. I spent a lot of time with my grandmother. I have this grandmother-based skill set. I know how to grow and sew and cook. My mother knew how to do that stuff, too, but ... she was a teacher."

After putting up the tomatoes, Melissa took off for law school and out into the world, knowing full well that certain people would face her with disapproval because of where she was from — and fully expecting that none of those people would appreciate the value, the love and the care bound up in the things she and her Granny Booth did with food.

Hall wound up in Oxford in 2001 when her husband, also an attorney, took a position at the University of Mississippi School of Law. She attended the SFA’s 2002 symposium on barbecue in Oxford and liked it, so she volunteered to help out at the next year’s symposium.

The 2003 symposium was titled “Appalachia: Exploring the Land and the Larder.” She watched fellow Kentuckians talk about the country hams they were curing, the cider they were fermenting and the heirloom seeds they were saving.

“As a person who grew up in Appalachia and was steeped in all that entails,” she says, “that Appalachian symposium was one of the first times I understood fully that there were people who believed the place I was from had value. It was incredibly important to me, just in my understanding of my own place and in the joy of finding these people who believed that my place had value.”

Two years later, Melissa took a full-time job with the SFA.

“When I graduated from law school,” she says, “I asked for two things for graduation: a briefcase and a good skillet. I got both, but the briefcase is in the closet.

"The skillet gets used all the time.”

Sara Camp Arnold

Melissa’s colleague, Sara Camp Arnold, sits and listens to her colleague’s story and then tells one of her own, but from a very different perspective. Sara Camp (run them together when you say it, like Sara Jo or Sara Jane) grew up in Raleigh, N.C., in surroundings and circumstances far different from Melissa’s childhood experiences in eastern Kentucky. When Sara Camp was 14, her parents sent her to the Groton School in Massachusetts, one of the most prestigious prep academies in New England.

“When I went to boarding school, one of my eighth grade teachers said to me, ‘You know, I don’t want you to let anyone tell you you’re not smart because you’re from the South,’" Sara Camp says. "And I said, ‘Why would they do that?’ I had no idea.”

Experiences such as the ones Melissa and Sara Camp describe stay with you. To hear that you are not good enough, that you are somehow deficient simply because of where you’re from … that hurts. It stays with you. It scars you. Doesn’t matter if you’re a hillbilly or a prep schooler.

The SFA attracts — to its staff and to its membership — people who bear just such scars. Why? Because the SFA is an institution that will help you take the chip off your shoulder and crush it into a thousand little pieces.

And do it in front of everybody.

Of course, no productive dialogue occurs — even over a cornbread-laden table — unless all parties try to see the situation through the others’ eyes. Or, as John T. puts it, “You got to own your own shit first, before you can talk about what a good place you have.”

We’re coming up on the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was, to put it bluntly, our nation’s way of telling the South that it was time to own our shit. Sometimes we forget that when President John F. Kennedy in 1963 asked Congress for legislation that would give “all Americans the right to be served in facilities which are open to the public — hotels, restaurants, theaters, retail stores, and similar establishments," our region stood in concrete opposition to the idea of a truly common table. The U.S. Senate’s final version of the Civil Rights Act passed 73-27, with only one of the yes votes coming from a Southerner, Sen. Ralph Yarborough of Texas.

This fall, the SFA’s 14th annual fall symposium will be built around the anniversary of the Civil Rights Act.

“Our focus is going to be on marking the Civil Rights Act’s anniversary and asking questions about inclusion and exclusion,” John T. says. “And I wonder, who else will we draw into our orbit? And who might we drive away? What happens when you become more overt about something that’s always been beneath the surface and shout it through a megaphone?”

Good question. And given the fact that at previous SFA symposia people have almost come to blows over the right way to make biscuits, this fall’s event promises to be a barn-burner.

“I think Southerners for so long have had a chip on their shoulder about so many of their cultural products,” John T. says. “So many people for so long have dismissed blues as gutbucket or bluegrass as … pick your pejorative … hillbilly, And we have just accepted this prevailing sense that Southern food is just grease and grease and grease. We haven’t, until recently, defined it ourselves. We’ve let other people define our region. And that’s because we were too embarrassed to speak up.”

But these are different days, John T. believes.

John T. Edge on the front porch of the Barnard Observatory on the Grove at Ole Miss

“What starts happening in the ’80s and ’90s in the South is that there is enough distance from the horrors of the Civil Rights Movement — the bad actors of the Civil Rights Movement, the guilt so many white Southerners feel for how they treated black Southerners for so long, there’s a generational break there,” he says. “Those are now the sins of your fathers, not your own sins. And there’s a dawning pride that Southerners begin to take in the ’80s and ’90s.”

John T. draws an analogy between Southern food culture today and the music scene that sprang up in Athens, Ga., in the early 1980s. He reminds me when People magazine wrote about the scene in 1983. I was in college in Athens myself at the time. The People magazine photographer captured a “family portrait” of dozens of young musicians — people from bands such as R.E.M., Pylon and Love Tractor — gathered around the old Clarke County Confederate Memorial in downtown Athens. I remember how proud I was that this new, weird South, of which I felt a part, was getting national recognition. It felt liberating somehow.

“They were claiming the South for themselves, but in a far different way,” John T. says. ”I think that started happening all across the South, in many different art forms, in the 1980s and ’90s. And I think what we’re seeing now is the fruit of that. We still have that debt to our past — the knowledge of bad deeds tolerated. But now there is a freedom of the people to look around, to say here’s this good thing — here’s this totem of our place, whether it’s music or food or literature or whatever — this thing that our biracial culture created, and let’s take that thing and lift it up. Let’s celebrate it. If we can find common purpose at the table, then that may be a possible salvation.

“There are two things happening at once now, I think,” he continues. “Southerners are taking more pride in all their cultural outputs. And the newest, hottest output in which they’re taking pride is their food. There’s a moment in the evolution of American food culture that I think we’re right in the middle of, wherein those working-class pitmasters are valorized or considered in the same way that white-tablecloth chefs are. Rodney and Samuel are on the same pedestal as Frank Stitt or close to it. They stepped on that pedestal together, black and white, and we’re framing a story now that says: Understand the value of what these men do, and understand it in the same context as Frank Stitt.”

For three days, John T. Edge and his colleagues had repeatedly mentioned the idea of putting working-class Southern food folks on the same pedestal as the classically trained vanguard of modern Southern chefs. And it seemed like every time I heard the word “pedestal,” it was followed by some variation on “with Frank Stitt.”

I decided I should probably ask Frank Stitt how he felt about sharing the pedestal, so Tamara and I headed for Birmingham.

I have been fortunate enough in my life to have had dinner at a few of the world’s greatest restaurants. Walking into the Highlands Bar & Grill for the first time, I felt something I’ve only experienced in the very best of those places.

Some folks think the best restaurants in the world are all snooty places, playgrounds reserved only for a certain, very high class of people. But in my experience, the best of the best create the feeling that all are welcome, that no matter what you’re wearing or how twangy your accent or how wide your ass is, you are welcome to share in the joy that happens when food is prepared exquisitely and perfectly.

I could feel that welcoming vibe the minute I walked into the Highlands, but when I ate Stitt and crew’s food, I tasted something I’d never experienced at any of those other places. I tasted home, distilled to its highest and purest form.

Frank Stitt was feeding me the best meal of my Southern life.

Born in 1954, Stitt grew up in Cullman, Ala. The son of a surgeon, he left the South after high school and eventually wound up at the University of California at Berkeley, where his study of philosophy led him to an interest in food. He talked his way into a kitchen job at Alice Waters’ legendary Chez Panisse in downtown Berkeley, where French-trained chefs were displaying a then-unheard-of, almost militant dedication to local ingredients. His next stop was France, but while he was there, he had an epiphany: He could apply the French technique he’d learned and French culture’s outsized love of food to the products of his native Alabama. So why not come on home?

In 1982, Stitt opened Highlands Bar & Grill in downtown Birmingham. Thirty-two years later, it’s a Birmingham institution. Stitt and the Highlands have won just about every award the food world has to offer, but he’s never gone the star-chef route. He’s still in the Highlands kitchen almost every night. His avoidance of the limelight means a lot of folks still don’t know his name, but in the community of Southern chefs, he is the granddaddy. When it comes to Southern cuisine of the highest order, Frank Stitt is, without dispute, The Man.

Frank Stitt in the Highlands kitchen

Frank and his wife Pardis, the daughter of Iranian parents who was born in Texas and grew up in Alabama, have been part of the SFA from the beginning. In fact, in John Egerton’s 1999 letter inviting the original founders of the SFA to gather in Birmingham, there is the line: “We will meet all day and then adjourn to Highlands Bar & Grill, where Chef Frank Stitt and his wife Pardis will be our hosts for drinks and dinner.”

Pardis and Frank

“From the beginning, we were trying to celebrate the humble Southern ingredients,” Stitt says. “That’s always been the core of what we do. Still, it could have been really easy for somebody like me to be focused only on super quality or the best ingredients. But John T. and the SFA are so inclusive and so democratic. They really insist on bringing in the inexpensive and the common. It’s wonderful. It’s not an elitist thing.

“The SFA has put us in touch with people like the Hitts in North Carolina, which in turn put us in touch with the people who make the Muddy Pond Sorghum in Tennessee,” Stitt says. “I had memories of sorghum syrup, mixing it with butter and putting it on a biscuit, but I probably never would have used it otherwise. I probably never would have touched ramps, but when I saw that film with Allan Benton cooking all that bacon with ramps and potatoes, man, those things are transformative.”

So there it is. Frank Stitt doesn’t just welcome the SFA’s farmers and syrup millers and pitmasters up onto that pedestal with him, he views them as an essential part of his life. Because they are there, his creativity as a chef and a restaurateur are less limited. They connect him to his memories.

And they allow him to connect his patrons to their own.

When I was young, my daddy’s greatest pleasure was quail hunting. I grew up with my stroller guarded by his hunting dog, a German shorthaired pointer named Rusty, who, after my mom, was the great love of my father’s life. The delicate meat of those little birds was part of my childhood.

That night at Highlands, I had an appetizer of Stitt’s quail pie. In the kitchen, they’d braised a bunch of quail until the meat fell off their bones. They added vegetables to the braising liquid, cooked it down and thickened it. Then they added back the quail meat and poured the whole mess into a perfect, lard-enriched pie crust with a beautiful brown lattice on top.

It was perfect. It was like they’d cooked cherished moments of my own history and fed them back to me.

Stitt’s food was knocking open those rusty gates between what we used to see as The Low South and The High South. I grew up in The Low South, in Appalachia, but here I was in The High South, in a big-city restaurant, eating the same lowly birds that Rusty used to flush out of the autumn stubble fields for my dad and me.

I felt the boundaries of class disappear as I ate that quail pie. I heard John Egerton's "rusty gates" creak open. I wanted to run out onto 11th Avenue South and holler: “Oil up them hinges, y’all. This time, we’re coming through. Together!”

I’ve now spent quite a lot of time all up in the SFA’s stuff. I’ve studied it. I’ve asked a lot of questions. I’ve learned a great deal. Rolling around in the crazy quilt of stories that the SFA has assembled has shifted my perspective on the South. It has renewed my appreciation for and pride in the foods and foodways I grew up with. It has made me remember how my father loved to end his meals with a biscuit smeared with a mixture of sorghum and home-churned butter. It has made me remember and appreciate anew how much time my Uncle Efford spent in the little smokehouse behind his home, curing and smoking hams cut from the hogs that, a few weeks earlier, he had sent me to feed with a bucket of slop, the scraps of our own supper.

But the renewal of precious memories cannot, by itself, constitute hope for a benighted region like the South. In fact, you’d have to be blind not to recognize that our regional obsession with memory often gets us in trouble. It can push us to preserve that which is unworthy of preservation.

Despite this, the SFA’s work does give me hope for the future of the South. I found that hope in the youngest members of the SFA crew — people like project coordinator Emilie Dayan and grad assistants Lindsey Reynolds and Anna Hamilton, all of them still in their 20s.

In 2012, Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce released a broad study titled “A Decade Behind: Breaking Out of the Low-Skill Trap in the Southern Economy.” The study documented one of the chief reasons that the South consistently lags behind the rest of the nation: brain drain.

“Brain drain tends to occur when your state is not producing jobs for college-educated workers or people with a degree or technical certificates,” noted Anthony P. Carnevale, the center’s director and one of the study’s co-authors. “Generally what happens is if you produce more college-educated workers than people are looking for and the wages aren’t as high as elsewhere, the people would leave.”

Brain drain is one of those chicken-or-egg economic problems. A region’s young people will leave it if it offers them no opportunity, but you always wind up asking yourself, if we’d found a reason for them to stay, would their influence have created the jobs we needed in the first place?

Lindsey Reynolds and Anna Hamilton

I remember sitting in the observatory back in December and talking to first-year grad assistant Lindsey Reynolds. Lindsey grew up in Austin, Texas. She graduated from the University of Texas and worked in corporate communications at Southwest Airlines for a while, then spent a few months in Paris, trying unsuccessfully to make it as a nanny. Now, at age 29, she’s studying at Center for the Study of Southern Culture, because the work of the SFA inspired her to come to Ole Miss.

“This is probably a very simplistic and idealistic view, but I feel like the South lost a lot of really talented young people because they think there aren’t jobs and opportunities, or they think it’s a backward place and they need to go to Chicago or New York or San Francisco,” Lindsey tells me. “Those are the very people who need to stay in the South and encourage its development. For me, that’s what made me want to come back and actually work in the South.”

Anna Hamilton, a second-year graduate student who had also spent time abroad before enrolling at the center, echoes her colleague. Anna grew up in Sarasota, Fla., the child of parents from West Virginia and Alabama. “My brother and I were the first generation born in Florida,” she says. “For me, the SFA is about dispelling stereotypes and doing it by engaging with where you live and where you’re from. It’s putting your roots down again, I guess.”

Emilie Dayan, the SFA’s full-time project coordinator, has a similar story. Emilie actually grew up in Oxford.

“As an undergrad I did international studies and economics,” she says. “I always thought I’d go into policy. I did an internship in D.C.

"I won’t name names, but I was on the Hill." she says. "And I was so disappointed in how this leader of my state, at the highest levels, was so disconnected to what was actually happening in the state. The things he was concerned with were things that were not helping our state progress socially and economically. My dissatisfaction with that experience led me to thinking that whatever I do, I want it to be more local, more grassroots.”

So, like Lindsey, she decamped for Paris and worked for a year as an au pair while attending graduate classes. She intended to take her knowledge and apply it to grassroots economic-development issues in the third world. But after a few months in Paris, her intentions changed.

Sara Camp Arnold and Emilie Dayan at work

Emilie was working for a family in Paris’ ritzy 16th arrondissement. “The 16th is where there’s like the only remaining aristocracy in Paris,” she recalls. “I literally met people who said they wished the revolution hadn’t happened, like it ruined their lives. They talked about it as if they’d lived through it. That was culture shock.”

It reminded her, she says, of Southerners holding on to twisted memories of their “noble cause.”

“That’s when all the pieces came together,” she says. “I knew I didn’t need to go to Africa or Asia. I’m from Mississippi, and I love Mississippi, and there’s a lot of work that can be done here. I’ve always been very passionate about the idea that the arts and culture play a really big role in economic development, especially in Mississippi. In the South, we have such a rich cultural heritage. In a state like Mississippi, where traditional means of development haven’t really worked, I think the key is going to be using culture. To me, that’s what the SFA does.”

Three young Southern women. Smart, highly intelligent, talented — all of them capable of doing whatever they choose to do, anywhere in the world. And all of them choose to return to the South to make our region a better place for the next generations. That fact alone justifies the SFA's entire existence.

Are these women the vanguard of whatever the South will become in the future? I pray they are.

I also pray that the SFA will keep finding people like Rodney Scott, the African-American barbecue pitmaster from South Carolina, and telling the world about them. Not so much because I want the world to know about people like Rodney, but because I want young Southerners like him to see the broader world — and to see how their talents, the things they learned at home in the South, might help others.

A few days before I went to Oxford, the cookhouse at Scott’s Bar-B-Q burned to the ground. It’s going to cost Rodney and his family more than $100,000 to rebuild, so several of his SFA friends — calling themselves the Fatback Collective — have organized something called the “Scott’s Barbecue in Exile Tour.” As you read this, Rodney is touring the great restaurants of the South, cooking whole hogs and working with chefs such as Kevin Gillespie, Sean Brock and Donald Link (and, of course, Rodney’s buddy, Sam Jones). The proceeds from the dinners they throw will go toward the rebuilding of the pits and the cookhouse back in Hemingway.

The main store at Scott's survived the fire, but the cookhouse and pits did not.

Rodney feels a little funny being on the receiving end of this help, but his friends keep reminding him that he’s cooked at quite a few benefits for other folks.

“It’s surprising some of the events people reminded me that I was a part of, and when they remind me, they say that’s why they’re going to help me,” he says. “But that was just me being me. I don’t help people for recognition.” He helps when help is needed, he says, because that’s what he learned in Hemingway, where sharing food throughout the community is a way of life.

“There shouldn’t be homeless or hungry people in America,” he says. “That’s just what I believe.”

Rodney Scott on his store's front porch

“I haven’t mentioned this to anybody else, but I’ve always thought that we food people can bring those memories back,” he says. “We who do the parties and the events and fundraisers, we can remind other people that it’s not a bad thing to maybe, every now and again, help your neighbor.

“I think this isn’t just going to be good for us. This is going to be great for the entire country.”

From his mouth to God’s ear.

Joe York: The Scorsese of Southern Food

The SFA's lead filmmaker has spent more than a decade bringing Southern foodways to the wider world.

All photos of Rodney Scott, Sam Jones and their respective BBQ joints from SFA Oral Histories. Sidebar photo of Joe York by Hollis Bennett. All other photos by Tamara Reynolds.

Next Week :

Through Maudie's Eyes

Next Tuesday, we stay in Mississippi to visit with one of the South's most iconic photographers, Maude Schuyler Clay. And we meditate on the question, What does the word "home" really mean?