Photo courtesy of IYO Visuals

Charlie Braxton, our guest editor for this week’s feature and an authority on Southern rap, explains the evolution of chopped and screwed and the young DJ, known as DJ Screw, who put Houston hip-hop on the map.

by Charlie Braxton

I remember the first time I ever heard a Screw tape. It was in the summer of 1998, and I was riding in a friend’s car near my home in Jackson, Mississippi, when he popped in a DJ Screw tape to get my feedback. My first reaction was telling him that his tape was dragging. (Remember how tape decks used to eat tapes?) It doesn’t take long to get from one end of Jackson to the other, and the song wasn’t even finished by the time we got to where we were going. It all seemed too slow.

To someone outside of the Screw community, it seems weird to listen to music that’s been slowed to a snail’s pace exclusively, but, like sushi, screw music is an acquired taste and enjoyed best on its home turf.

You can appreciate the music superficially as an outsider, but until you travel to Houston and immerse yourself in the city’s hip-hop culture, you’re not going to truly understand screw music. It took me several trips to H-Town covering the city’s hip-hop scene and hearing screw music blaring out of various peoples’ cars that I came to understand and respect the genre.

My true epiphany happened back in the summer of 2007 when I flew to Houston for a music conference. My friend, DJ Dirty Dave of Street Pharmacy picked me up from William P. Hobby Airport bumping his group’s latest mixtape. I hopped in and we hit the slab (the highway) headed for the venue. Typical of most young Texans back then, Dave had a huge car with a stereo that had an even bigger sound. It took us a full 30 minutes to get to the venue and the music stretched to fill the time in the car. I remember listening to what seemed like a 10-minute chopped and screwed version of Slim Thug’s song “Boss Hoggin’” and thinking to myself, “Life doesn’t get any better than this.” I had become a bonafide screwhead.

DJ Screw had passed away seven years earlier, but he had created a sound that represented Houston. He didn’t just change how I listen to music, he made a lasting impact on hip-hop. Whether you are just learning about DJ Screw or a longtime fan, hop in and I’ll take you for a spin through his legacy.

The evolution of the mixtape runs parallel with the growth and development of hip-hop culture. In mid-70s New York, hip-hop fans would go to park jams and parties and make homemade recordings of pioneering DJs, such as DJ Hollywood, DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, Grand Wizard Theodore, and Grandmaster Flash, and sell or trade these tapes to other fans. These homemade copies would be copied many times over and sold up and down the East Coast, eventually making their way around the country, spreading hip-hop culture wherever they were played.

In the ’80s, DJs like Brucie B decided to get in on the act, recording and selling professional quality tapes of their DJ gigs. This gave way to DJs such as Kid Capri, Doo Wop, and Ron G who took the genre even further by introducing exclusive music, remixes, and freestyles into the mix. At this point, the mixtape had begun to gain some national popularity with hip-hop fans globally, but in the ’80s it was still largely an East Coast thing.

All that would change by the late ’90s when Southern hip-hop finally came into its own with groundbreaking artists like UGK, the Geto Boys, Outkast, Goodie Mob, and 8Ball & MJG. Along with the rise of these Southern-based artists came a slew of mixtape DJs such as DJ B-Lord out of South Carolina and DJ Jelly and DJ Drama out of Atlanta.

But, of all of the Southern mixtape DJs, no one has impacted hip-hop like the late Houston-based mixtape king/producer, DJ Screw, creator of the turntable technique known as chopped and screwed or Screw Music as it is commonly called by fans known as “screwheads.”

To this day, Screw tapes are held in high esteem throughout the Southwest and the rest of the world. They are copied and circulated via fans on the internet, mom and pop stores, and street vendors, also known as bootleggers.

“Screw is [like] DJ Clue or Funkmaster Flex down here,” says Marcus Edwards, better known as Lil’ Keke, a member of DJ Screw’s collective of rappers known as the Screwed Up Click. “When he was doing the mix tapes that shit was like it. At one point in time that’s all people was really listening to was them Screw tapes.”

In 1989, Screw, who was born Robert Earl Davis Jr., got his name from his friend Shorty Mac due to his penchant for scratching up records he didn’t like with a screwdriver. Screw was an aspiring young DJ who struck ghetto gold when he accidentally slowed the pitch on his turntables while imbibing alcohol and smoking weed with friends. One of his friends heard the results and said the records sounded pretty good, so he asked Screw for a copy of the records slowed down for his own personal use.

“Screw thought the guy was crazy,” Charles Washington, the DJ’s former manager, told the Texas Monthly. But he did it.

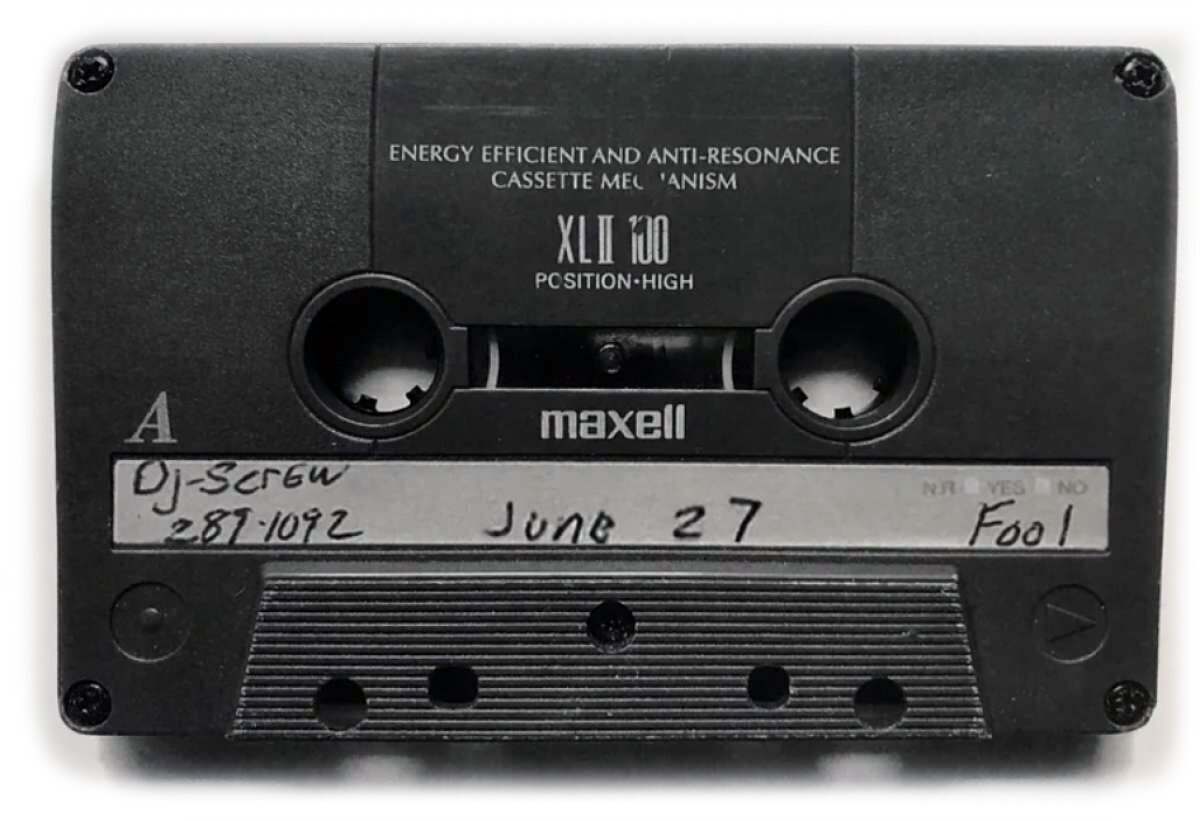

Friends started lining up to buy copies of Screw’s slowed down mixes recorded on green Maxell chrome cassettes. That was the beginning of a phenomenon that would immortalize the Houston resident and make an accident into a genre of music that changed the face of Southern hip-hop forever.

“It was a scene around those tapes,” Lil’ Keke recalls. “You used to go to Screw and give him a list of songs that you wanted, pay him $15 and he’d put all the songs you wanted on there. Now he was going to scratch it up and put his little thing on there, and before you know it, you had a tape that he’d sell to other folks. You’d have folks from Fifth Ward, Third Ward, Botany, Dead End, and other hoods would have their own tapes out, and people from all over the city would buy them. It was a big thing. Screw was selling a thousand tapes a week at $10 a pop.”

The best way to describe a screw tape to those not familiar with the genre is this: Imagine playing a 7-inch 45rpms record at 33 1/3 rpms, add a little cutting and/or repetition of keywords (also known as chopping), and you have some inkling of an ideal of what a screw tape sounds like.

“It caught me by surprise because it was so different from what was normal,” says Paul Slayton, better known as Paul Wall, of Swishahouse. “But, that’s why I liked it because it was different. Then, eventually, I got used to it and it came to a point where the music didn’t sound right to me unless it was screwed.”

By 1996, DJ Screw’s slow mixes started to move outside of Texas. People were driving from as far as Mississippi to get Screw’s tapes. They had become so popular that a crop of other screw DJs followed in his footsteps, and a number of Southern rap artists such as 8Ball and MJG would solicit spots on popular screw DJs mixtapes because they understood what it could mean for their career.

According to Dirty Dave, a spin on the latest “Screwtapes” by DJ Screw’s musical progeny, Michael “5000” Watts, Beltway 8, or OG Ron C in the early 2000s could boost record sales by as much as 10% in the Texas/Louisiana markets alone. “Back then, being on those Screwtapes would expose a new artist to thousands of fans,” Dirty Dave says. “Sales and demand for shows [would] shoot up. It was like having a major co-sign around here.”

Another vital part of DJ Screw’s mixtapes was the regular appearance of local rappers who freestyled over the latest hit instrumentals on his tapes. Known the world over as the Screwed Up Click, these Houston rappers would drop exclusive freestyles on various screw tapes, which gave them instant celebrity status in Houston. The S.U.C. included rappers who went on to successful national and regional rap careers such as platinum-selling rapper Lil’ Flip and the late Big Moe, both of whom had screwed versions to their albums released along with the regular versions, even though they were signed to major labels. Other members of S.U.C. included Lil’ Keke, Al-D, Fat Pat, Big Hawk, Big Pokey, Z-Ro, Trae Tha Truth, the Botany Boyz, and E.S.G. Another budding MC who graced one of Screw’s mixtapes with freestyles was George Floyd (aka Big Floyd), whose senseless slaying by a Minnesapolis police officer sparked massive protests across the country.

The S.U.C.’s freestyle tapes became so popular that DJ Screw was offered a record deal by Bigtyme Recordz, a small indie label based in Texas. He released a series of mixtape albums called “3 ’n the Mornin’ (Parts One, Two, and Three)” (Bigtyme Recordz), “All Work No Play” (Jam Down Records), and an album full of original material with his group, DEA (Dead End Alliance), called “Screwed For Life” (Dead End Records).

Boasting DJ Screw’s classic laid-back production, rich with slow-winding melodies similar to that of the West Coast G-Funk only, “Screwed For Life” is a tad more bass heavy and considered a classic by fans of Texas underground music. The DEA record marked Screw’s transition from DJing to producing and laid the blueprint for many Southern producers. One was UGK’s Pimp C, whose stellar production on the Mississippi-based rap duo Crooked Lettaz single “Get Crunk,” is heavily influenced by Screw and Three 6 Mafia’s DJ Paul and Juicy J’s “Sippin’ on Some Syrup” that owes as much to DJ Screw as it does to the beverage that the group pays homage to.

Speaking of syrup, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the unfortunate role that lean, aka purple drank, syrup played in the Screw phenomenon. With a key ingredient being a prescription-only cough syrup containing codeine and promethazine, lean makes the world seem like it’s moving in slow motion. The drug was largely a Texas thing, but it was introduced to the broader hip-hop community as the music gained wider popularity.

DJ Screw insisted that you didn’t have to get high to enjoy screw music. “People think that you gotta get high, gotta get fucked up, do drugs just to listen to my music,” Screw once told Murder Dog Magazine. “It ain’t like that at all. You don’t gotta get high to listen to my music. … It ain’t about that. I’m just bringing it to you in a different style where you can hear everything and feel everything.”

Sadly, Screw succumbed to an apparent overdose on Nov. 16, 2000. It was initially reported as a heart attack, but rumors soon spread throughout the city that his heart failure was caused by “too much lean in his cup.” Later, coroners revealed that his death was wrought by an overdose of codeine, and other drugs were found in his system.

The death of DJ Screw sent shock waves throughout the Screw community, but many fans take comfort in the fact that his legacy lives on in other chopped-and-screw crews such as Swishahouse. Remnants of Screw’s legacy can also be found in the music of current hip-hop artists like Drake and Travis Scott.

Once dismissed as a regional cult phenomenon that would go no further than the Houston area, the music that still bears DJ Screw’s name has grown into an international phenomenon, with fans from Japan, Germany, and Russia still making pilgrimages to the original Screwed Up Records & Tapes shop on 7717 Cullen Blvd., before heading off to purchase authentic DJ Screw tapes and merchandise at the current Screwed Up Records & Tapes on 3538 W. Fuqua St.

Come this July 20, DJ Screw would’ve turned 50 years old. With a plethora of tribute songs, a documentary due to release this fall, and a forthcoming biography, DJ Screw: The Texas Turntablist Who Slowed Down the World by Lance Scott Walker, DJ Screw’s legacy will be cherished by his fans the world over. The University of Houston has also added DJ Screw’s personal vinyls, tapes, and photos to its special collection archives.

“I think that screw music is going to end up becoming its own category of music,” says Micheal Watts of Swishahouse when asked about the future of screw music. “Just like rock, pop, or reggae have become their own genres. I think that it’s going to be respected as an art form instead of fad.”

Charlie Braxton is a poet, playwright, and music journalist/historian based in Jackson, Mississippi. His work has appeared in magazines around the world, including Vibe, The Source, and XXL. Braxton served as guest editor for “Southern Hustle: Houston Hip Hop and Chinese Chicken.”