Students in Ellen Engelmann’s art classes at Hayesville High School found belonging, healing, and perspective that took their hearts and minds beyond the confines of rural, homogenous western North Carolina. As schools across the country make massive budget cuts, arts education might well be among the first casualties. A retired English teacher and former colleague of Engelmann’s makes the case for art as an essential element in a quality education, mental health, and preparing people to participate in a more just and equitable society.

By Marianne Leek

May 28, 2020

When Bailey Johnson was a student in my American literature class at Hayesville High School, she read the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and “Stride Toward Freedom,” and Les Crane’s interview with Malcolm X, “Necessary to Protect Ourselves.” We also read “Red Jacket Defends Native American Religion, 1805” and “I Am Joaquin.” We read these in conjunction with Patrick Henry’s “Speech to the Virginia Convention,” some of Abigail Adams’ letters to John Adams, and the Declaration of Independence. I asked students to consider if and how the fundamental beliefs of our nation had changed since its inception.

My students worked together in groups to pose questions that connected both sets of readings with current and historical events — all around one core theme: the fundamental rights of every human being regardless of nationality, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic circumstances, or political affiliation.

The combination of these readings sparked intense Socratic discussions in our rural Appalachian classroom about racism, politics, human rights, and historical and current social injustices. Johnson’s reaction to these literary works and our class discussion carried over into the art classroom, where she started working out her own inner conflict and frustration about what she had read and discussed with her classmates.

Once she had moved on to an art class under my friend, art teacher Ellen Engelmann, Bailey’s learning and thinking fueled a painting she called “Malcolm X.” One afternoon, she brought it into my classroom, because she needed a place she could leave it to dry. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

I asked her to tell me about her choice to paint Malcolm X.

“I knew little of Malcolm X, but I had some concept in my head of Martin Luther King Jr. versus Malcolm X, as if they were opponents in a match. Martin Luther King Jr. was associated with an air of peace while Malcolm X brought images of violence and outrage. However, after we read the interview, ‘Necessary to Protect Ourselves,’ my previous impression of Malcolm X seemed absurd in contrast to what I was reading. How could I blame a man for refusing to lie down to be beaten in the street? How could I call him violent, under the circumstances he endured, for protecting himself when his society and government would not? The Jim Crow South built an association between Malcolm X and violence, because they feared what the oppressed were capable of should they stand up. This idea is still ingrained into the minds of many Southerners today, perhaps only faintly but still so, and I know this to be true because I recognized it in myself. When I finished the painting, his eyes alone seemed to ask: “Were you on the right side of history?” At times I imagined that the easel cradling this scene was almost too frail to hold its metaphorical weight. A sense of pride washed over me. After two months’ work, the image looked exactly as I had imagined it.”

Bailey set up a table of her artwork at a local craft fair in the summer between her junior and senior years. She remembers an interaction she had at the fair.

“Malcolm X” by Bailey Johnson

“‘Ah, Malcolm X. The good die young,’ said a man selling jewelry in the next tent,” Bailey says. “We struck up a conversation, discussing our common belief that Malcolm X is widely misunderstood and villainized. Our shared view of Malcolm X is of a man unafraid to stand up for himself, to grow through his mistakes and move forward. My tent neighbor was the only person throughout the day who recognized Malcolm X. This reminded me why I create: to show humanity a new world inside the old one.”

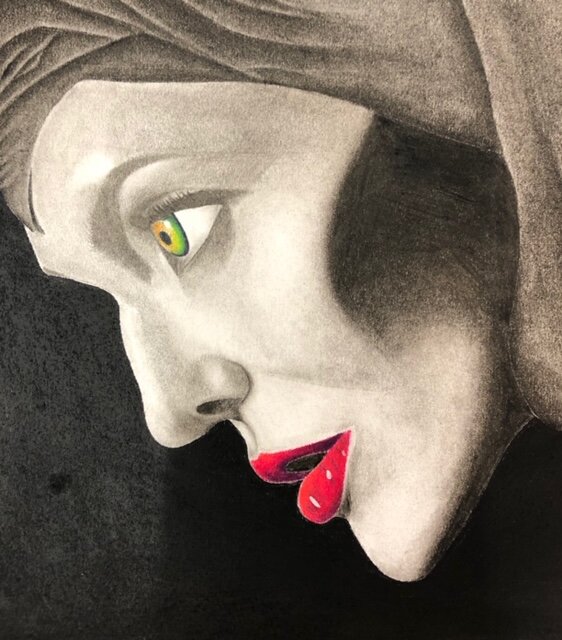

“femme” by bailey Johnson

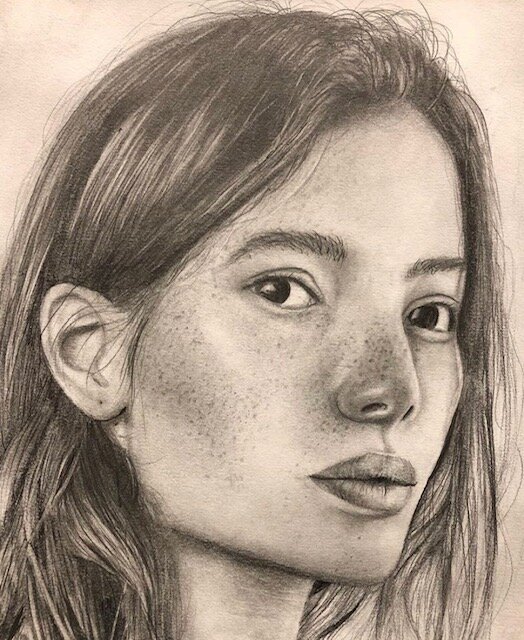

During her senior year, Johnson painted a piece called “Femme” to refute the homogenized, one-size-fits-all, American standard of beauty perpetuated by the media. Her art honors the authentic beauty of every body, regardless of its size, race, or age. Bailey explains the dichotomy of self-love in our society. “There’s something beautiful about loving the body they don’t want you to love,” she says. “When you see beauty in yourself without the permission of others, they get uncomfortable in your presence. Make them uncomfortable.”

Ellen Engelmann hasn’t always been a teacher, but she has always been an artist.

“My mother had a large library of books in our living room, many of which were about art,” Engelmann says. “I would spend hours looking through books about the Renaissance and artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I would spend my days daydreaming in pictures about anything and everything. Oftentimes, I was in trouble with my teachers for being off task or not paying attention because I was too busy lost in my own imagination.” She adds, “the act of making art is a vulnerable thing.” Because of this, she understands that her classroom must be a safe space for students. She has taught art for eight years at the same small K-12 campus in western North Carolina. On sunny days, it’s not unusual to see groups of students sitting on quilts in the spring sunshine working on drawings or writing in their art journals. You might even catch students during breaks doing yoga or handstands with Ms. Engelmann, while others have earbuds in, lost in music and their imaginations. She understands the importance of fostering a classroom climate of inclusivity, empathy, kindness, and compassion.

In her 1992 New York Times essay “Sanctuary of School,” the writer, cartoonist, and teacher Lynda Barry describes her experience with art — and one teacher who simply took the time to care. She writes that her teacher “believed in the natural healing power of painting and drawing.” She concludes her essay with a call to action: “We all know that a good education system saves lives, but the people of this country are still told that cutting the budget for public schools is necessary, that poor salaries for teachers are all we can manage and that art, music, and all creative activities must be the first to go when times are lean.” Barry demanded that our country pledge to take care of its children and increase funding for education. Twenty-eight years later, her message is still relevant. Since Barry’s essay was published, those at the forefront of education reform have come to recognize social-emotional learning and the importance mental health plays in students’ ability to learn.

In 2010, the Missouri Alliance for Arts Education published the results of a three-year study, “Art Education Makes a Difference in Missouri Schools,” examining the effects of fine arts programs on students’ academic achievement. This milestone study found that students who were involved in the arts consistently had higher SAT scores and performed better in both math and reading. This trend held true across racial and socio-economic groups. Students who were involved in the arts had a lower likelihood of dropping out of school, as well as higher attendance and graduation rates. While the study can’t conclude that involvement in the arts “causes higher academic achievement,” what it does seem to suggest is that involvement in the arts is directly connected to the social-emotional learning that is essential for students to learn and perform well. When it comes to education reform or funding art education programs, those in leadership are remiss if they fail to listen to the voices of those most directly affected — teachers and students.

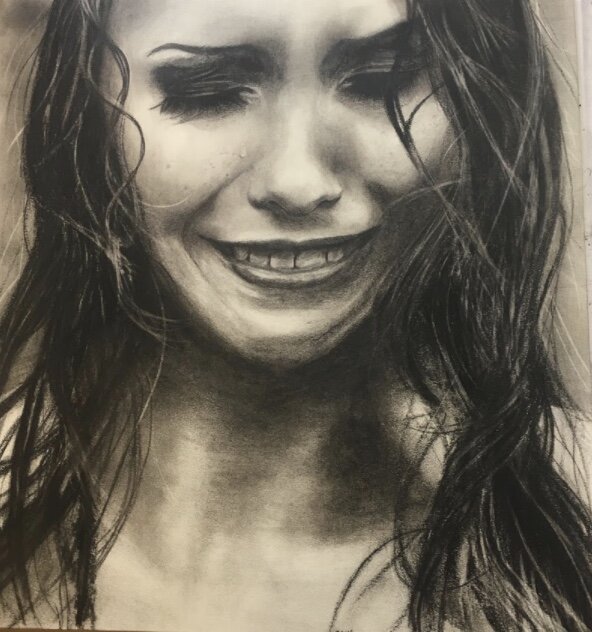

An untitled painting by Hayden Ledford.

***

Natalie Gray, a senior in high school in that same little high school, views creativity as a vehicle not only for self-expression, but also for exploring different points of view and beauty in other cultures.

“With all the beauty our rural community possesses, it lacks one major quality: diversity,” Gray says. “Diversity is a quality that potentially changes cultures, beliefs, and worldviews. It is a quality that is much needed in this isolated part of North Carolina, where the population is generally religious, politically conservative, and demographically similar.” She explains that sometimes small, rural communities can be “resistant to change and close-minded.” Some rural students, she says, “tend to exhibit these short-sighted tendencies. On countless occasions, class discussions come to an abrupt end after classmates are unable to consider the possibility of an opposing viewpoint. One of the challenges that teenagers are facing — especially in the rural South — is the ability to be open-minded and inclusive. Close-mindedness stops all inquiry which leaves a town, a nation, and a country that will refuse to learn and understand.”

Art gives Natalie a chance to decompress, too. “I have found that art, specifically drawing, has given me a break from the pressure that I put on myself to succeed,” she says. And she appreciates the value art has in helping students cope with mental health issues and the pressures of daily life. “While art gives me a break, it gives others the outlet to express feelings that they might not be able to express in their ordinary lives. It gives people the opportunity to put their heart and soul into something and then feel great when the project is complete.”

Allison Thomas, a high school junior in Hayesville, has also come to believe in the importance of art.

“Art is powerful, and I truly believe that it has the capacity to change others and the world. Art can inspire people, refute stereotypes, be used politically, and can shed light on issues that often go ignored or are misunderstood. Art can change the South and Appalachia for the better. Art has the potential to bring people together by allowing them to celebrate their culture with the world. Whether the art reflects Appalachian poverty, Southern traditions and culture, or Native American roots, it can have significant effects. People who live here might see someone’s art and know that they are not alone — that they are seen and the world knows we are here. People on the outside may come to a deeper understanding of people here, and it can show them how truly beautiful our culture and all cultures are.”

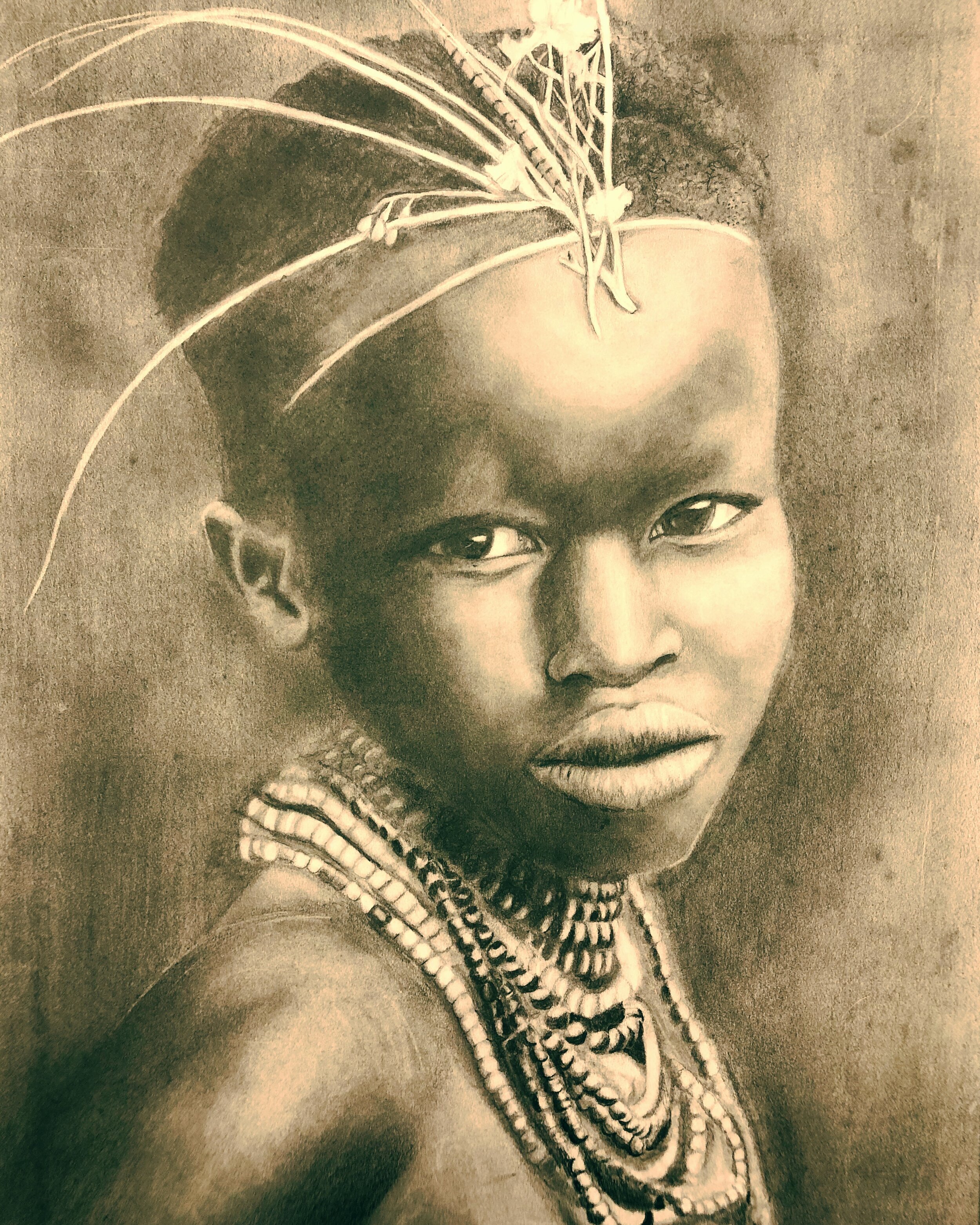

Sophomore Hayden Ledford talks about how art has changed his worldview because “it has helped me to better understand different cultures.”

For Nathan Lindsey, Mrs. Engelmann’s class was a sanctuary. Nathan’s father died when he was 7 years old, and since then he has been finding ways to cope with the weight of that loss. For an hour and a half during each school day, he found peace and solace in the paintbrush. He describes the cathartic effect.

“Art lets me express things about my depression, that no amount of therapy or medication has ever let me express,” he says. “Art gives my mind a break from everything. When you are creating, you cannot think about how much you do not want to be here, or how much you want to lay in bed alone. The only thing you are able to think about is how you just messed up and have to re-shade a whole section of your drawing. When you are hypnotized by your artwork, there is no bad, there is only you and your artwork.”

Nathan talks about how the challenges teenagers face too often don’t seem very real to adults.

“We all struggle,” he says. “We struggle with our friends, our significant others, and of course, we have the worst time with our own thoughts. In the rural South, one of the biggest challenges is being accepted by others. If you’re not ‘normal’ in a small town, then you are overlooked. If you're not ‘normal,’ then you are just another outcast. When you go anywhere in the mountains with piercings and long curly hair, people stare. People treat you differently, and they think you are less of a man; they think you are less of a person. Art class is essential for a lot of students. Some of us kids only get through the day because we know we have an hour and a half to do what we enjoy, to do what we love. The students that truly love art have an hour and a half of the best therapy you can get; they have an hour and a half to feel happiness.”

“Breakthrough” by Caleigh Chrisley. The first photograph shows the artist’s hand at work, the other shows the finished painting.

Another student, Travis Rutledge, talks about it this way. “Art brings out my emotions,” he says. “I think and contemplate all the time while wiggling my wrist and arm, and it helps me cope with problems such as anger, depression, and anxiety because sometimes I just need to let it out. It just kind of mellows me out. I’m not really a complex guy; I just really need something to allow me to deal with my raw emotions and allow them to come out on paper as a chaotically beautiful piece of art that just sucks all of the negativity out of me. There’s a different bit of me in each drawing or sketch, and I feel as if an artist should keep creating until they feel as if each little square centimeter of their soul is represented by their pieces of art.”

Still another, Dagen Robinson, explains how art helped bring her through the grief of losing her mother.

“Art is such a relief to me, because when I was 12 years old, my mom was diagnosed with a type of cancer,” Dagen explains. “I went through a rough time for a year and a half, only to find out I had two weeks left with not only my mom but my best friend. Those two weeks passed, and I found myself a freshman in high school who had just lost her mom to cancer. I felt empty. I felt everything but the person I was before. I took the first six months pretty easy. I felt like I was living life to its full potential with a few ups and downs. The next six months hit me, and I felt like I abruptly hit a brick wall. Her death is something I've been struggling with for over a year now, but I've learned to surround myself with people and things that make me happy.” And art is one of those things for Dagen.

Lizzie Davies talks about how art helped her learn to live with depression.

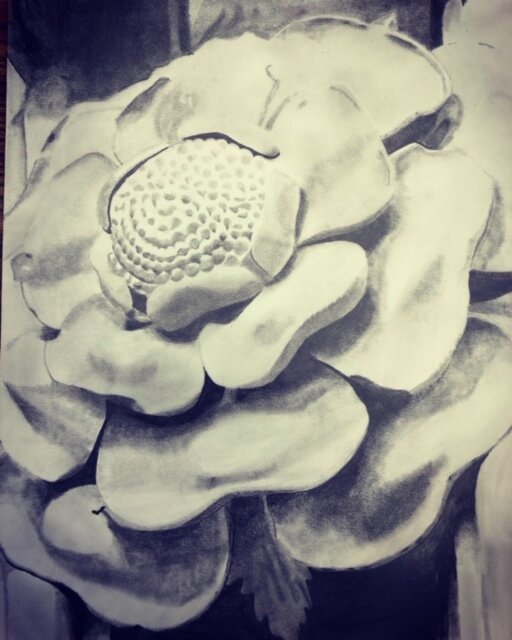

“I have dealt with depression for a few years now,” she says.. “It was first recognized when I was 14. During my freshman year, I felt lost. I had just gone through a very traumatic eighth-grade year dealing with lots of bullying, which caused my self-esteem to completely plummet. Freshman year was the year I got into Georgia O’Keeffe and started painting. I am now a senior, still battling the brick walls I am faced with each day. I am also still painting. I don’t want to give the impression that art is always just sunshine and flowers though. You have days where you are frustrated, days you wanna give up, and days you just want to say ‘to hell with it’ and throw it away. Pushing through and finishing a piece is another rewarding feeling you get when creating art. Pushing through the obstacles and figuring out which colors to blend together to get you that perfect mixture is a good feeling.”

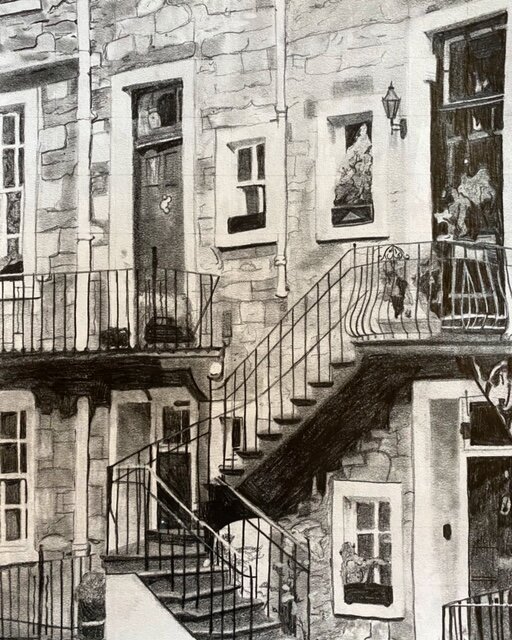

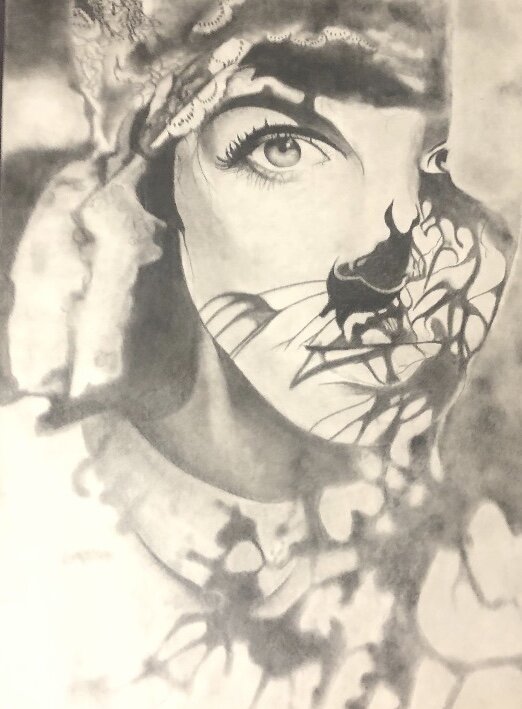

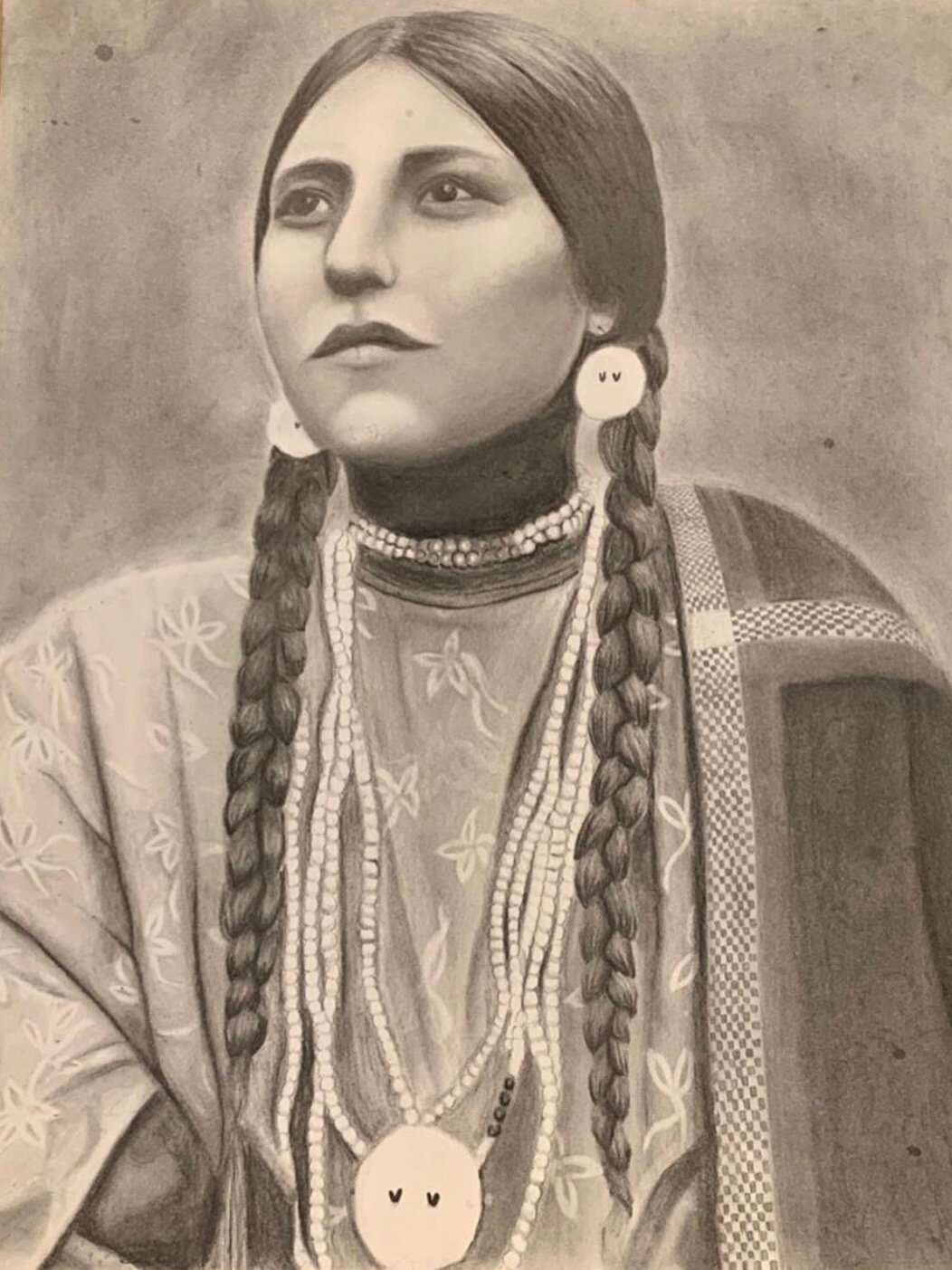

The artworks of present and former Hayesville High School students. In sequence, beginning with Natalie Gray’s early drawing “Doors of Edinburgh,” the other images are by Hayden Ledford, Piper Snowden, Hayden Ledford, Nathan Lindsey, Allison Thomas, Hayden Ledford, Natalie Gray.

Jessie Neumann, a former Hayesville High student now a senior at Appalachian State University, explains that he finds “art and writing as not only a means of therapy, but of survival. Creating something can be a powerful and healing experience.” Piper Snowden, now a student at Mars Hill University, echoes Jessie’s sentiment, explaining that she emotionally hit bottom when she went to college. After suffering in silence, Piper describes the catalyst that drove her to seek help for her depression. “I told him I wanted to be a writer when I grew up. I shared the last thing I wanted, the only thing I hadn’t given up on. That tiny dream had sat stagnant in the back of my mind, keeping me alive when I had nothing else, and that's what it means to be an artist. My unwavering love of the arts made me strong when I felt weak, and when I couldn’t fight for myself, I fought for my words. I want to be a writer. I want to tell people what happened to me. I want to be happy.I want the education I deserve. I want to have hope.”

***

Ellen Engelmann, like her students (like us all), struggles with feelings of inadequacy and questions whether teaching art to these mountain young people is enough. But she loves the transforming power of creativity that she gets to witness daily.

“I don’t know exactly what pain or trauma each student feels; I just know when art helps,” Ellen says. “In their art journals, they can express themselves as they choose. It is a private place for their thoughts and pictures. I know art helps when they come into my class during lunch to work on a painting. Or when they ask me to take home expensive colored pencils over the weekend so they can finish a drawing. Or when they bring their friends to our classroom to show them how their project is coming along. Or when they take pictures of their work and ‘Snap’ them to their story. I watch these things happen daily and it makes my heart smile. I hope my classroom is a safe place. It’s the things we do on the perimeter of life that make living so wonderful. Art, music, dancing, reading, hiking, running, playing … this is the lesson I hope they take from my class.

“I still think it’s funny sometimes that I am a teacher,” she concludes. “I picture myself as a student, and I imagine some of my former teachers laughing when I tell them my career. But then, I realize that all teachers are just people — people who care, people who enjoy the process of learning and teaching kids to learn. On second thought, my teachers would not laugh; they would rejoice that I have finally found something I can share with the world. As teachers, we see hope and light in all kids. We wish for their success and pray for their safety. I don’t remember many teachers who changed me as a student, but I can say that I remember many students who changed me as an adult. It is the greatest gift.”

***

Lizzie Davies finds relief from her depression in making art like this work in progress inspired by the paintings of Georgia O’Keefe. “You have days where you are frustrated, days you wanna give up, and days you just want to say ‘to hell with it’ and throw it away,” Davies says. “Pushing through and finishing a piece is another rewarding feeling you get when creating art. Pushing through the obstacles and figuring out which colors to blend together to get you that perfect mixture is a good feeling.”

So much has changed since I interviewed Ellen Engelmann and her students this past fall. In mid-March, teachers and students all across America abruptly and drastically altered the methods with which they teach and learn and ended the 2020 school year in a way they never anticipated. Bailey Johnson explains how she continued to turn to creativity while social distancing. “During a time of uncertainty, broken routines, and dealing weekly with the ghosts of milestones I would have been celebrating, art has kept me grounded. I am currently working on a painting using my friend Isabella as a model and attempting to create a modern symbol of the Roman goddess Venus. Since continuing my project from home, I have actually begun to develop more creative ideas, pay more attention to detail, and gather more motivation for the piece than before. I have used it to create a schedule where I no longer have a schedule, I have set goals for my art where I no longer have goals for school, I have pushed myself harder in my art where I can no longer push myself in sports, and I have something to look forward to where many senior events I should be looking forward to are gone.”

“During quarantine art has helped to keep me busy in a time where you can barely leave your house,” Natalie Gray says. “I think it is a way to put your focus into something you can control when the world is in a state where nothing can be controlled. It keeps me positive and optimistic when I look back at what I have accomplished, instead of wondering about everything I am missing out on. Overall, art has given me an outlet in this time of turmoil and I am very appreciative of it.”

The great Kentucky feminist Crystal Wilkinson writers, “Curiosity is the engine that drives creativity of any kind.” Therefore, a good teacher creates a classroom culture that affords students infinite opportunity to engage in curiosity and creativity — that must always be the goal of education. Creativity and imagination — art, music, and writing — have continued to bring many of us light and aided us in finding our way through these strange and difficult times. Now, perhaps more than ever, art is essential and creativity sustains us.

Creativity changes lives, yet art, music, drama, writing, and other academic electives are the first programs eliminated when federal and state funds are scarce. In the face of COVID-19, most states will see their already exhausted education budgets slashed dramatically, and it is doubtful that school in the fall of 2020 will bear any resemblance to school before the pandemic. So what does this mean for fine arts programs that already faced a lack of funding and possible elimination? What does this mean for students who struggle with depression and other mental health issues and rely on the connections and relationships they build with their teachers and classmates while at school? How do you cultivate a healthy classroom climate, where students can thrive, when the classroom looks and feels so incredibly different?

But the act of creating has the potential to positively and profoundly transform the creator, and student engagement in these classes can offer a place of refuge and belonging during the school day. Participation in creative endeavors is an integral part of a well-rounded education. As school boards around the South make the cuts they must, they must be aware that, perhaps now more than ever, art significantly impacts the social-emotional well being of students.

Because art can save a kid’s life.

Marianne Leek, a regular contributor to The Bitter Southerner, is a recently retired teacher from Hayesville High School, in North Carolina’s Appalachian Mountains. She offers her thanks to Ellen Engelmann, Bailey Johnson, Natalie Gray, Allison Thomas, Hayden Ledford, Travis Rutledge, Nathan Lindsey, Dagen Robinson, Lizzie Davies, Piper Snowden, Jessie Neumann, and Caleigh Chrisley for sharing their artwork — and their thoughts about the healing power of art — for this story.