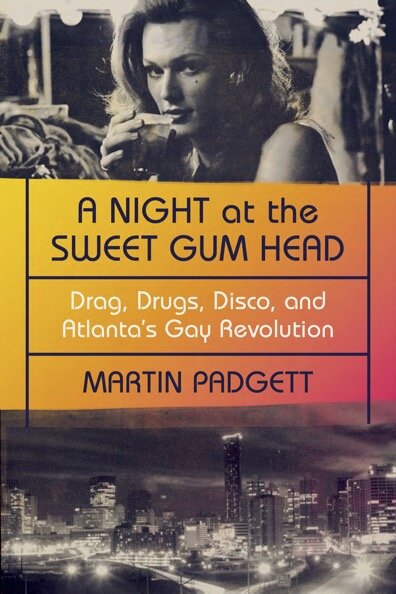

While Atlanta became an oasis for LGBTQ Southerners in the late 1960s and 1970s, it was no paradise — police often raided clubs, theaters, and parks. Martin Padgett’s new book, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution, reveals the history of the city’s beloved drag club and its early activism.

by Martin Padgett

Atlanta

August 1969-December 1970

They each paid a dollar to the cashier at the office desk in the narrow lobby, and made their way toward a theater cloaked in fireproof turquoise curtains — among them, a woman in tight brown curls and wide, hopeful eyes; a man eager to see breasts onscreen; a woman eager to see them too.

A red carpet laid out in Oscars style led them down the aisle toward Andy Warhol’s “Lonesome Cowboys,” in its third week at the theater despite terrible reviews. They whispered and giggled and chatted; the girl with wide eyes ate a submarine sandwich, while others munched on popcorn. They had filled about half the sea-green, rocking-chair seats when the Simplex projector woke up and lit the screen with images of naked bodies, quick-cut visuals, and non-sequitur plot points.

“Cowboys” had cost Warhol’s Factory just $3,000 to produce, and none of the money seemed to have been spent on the script. Men thrusted their pelvises in each other’s faces, the camera stared blankly at naked torsos and buttocks and breasts, and actors indulged in some lightly comic cross-dressing. The nonsensical parody of Western films grated on the sensibilities of high-minded cinema.

It also grated on the high-minded people who lived in the expensive houses near the Ansley Mall MiniCinema. They complained to the local police about its more lurid, even pornographic, moments.

The movie flickered in the dark, across gay and straight and lesbian faces, but in the lobby the scene exploded into action. Unknown men in suits swarmed in without a word. One stood guard in the lobby and set up a movie camera. Two marched into the theater, while a few stomped upstairs to the projection booth. Three more hovered in the lobby and locked the front doors from the inside. They said nothing to the cashier. They showed no identification. They had no warrant.

“It’s over!” an officer bellowed as the movie stopped and the lights in the theater startled the patrons. Police circled them like roaches they expected to scatter. They sneered at them, and asked one lesbian, “Where is your husband?”

“We’re being raided!” someone wailed, and it sounded like defeat.

The police demanded identification while a photographer took pictures to shame each one of them, as the flash on his camera scorched the air with a puff of chemical judgment. The theater’s 28-year-old manager, Joe Russ, sat in handcuffs, while the police movie camera kept its wide eye open as the dazed moviegoers filed out, confused and furious.

Hinson McAuliffe, the bald-pated Fulton County Criminal Court solicitor, had ordered the raid. He had gone to see the movie once he heard about the risqué content. He had found it obscene, of course — and boring. He said he fell asleep several times, and complained about the movie’s low caliber of photography and acting.

McAuliffe thought the movie and its viewers were deviant. He ordered photos and film of the audience so that he could recognize any “known homosexuals.” He wanted to check their police records for previous sex offenses. He vowed to raid more theaters and bookstores in Atlanta.

City leaders had painted the city as the picture of progress — but Atlanta in 1969 was a city with just a single skyscraper. It had anointed itself a New South before the old one was dead. Draconian obscenity and sodomy laws drew long prison sentences, and while heterosexuals regularly “watched the submarine races” at Piedmont Park after dark, gays and lesbians were harassed for walking there in daylight.

McAuliffe swore he had the community’s interests at heart, but some had already taken him to court, and lodged protests in letters to the editor and in calls to local radio stations. If police had the right to take a picture of them, one caller warned the prosecutor, they had the right to break the camera.

***

The world these gays and lesbians had inherited from their fathers and mothers was different from the one they dreamed of for themselves. War had ripped up the social compact and left no draft for the future. Some took that as a cue to huddle in fear.

Others took it as a cue to free themselves. They went on a pilgrimage to cities, where they could live more openly, though they still faced grave danger. Even in San Francisco and in New York, which seemed to have more homosexuals than any place on Earth, the police still raided gay bars and revoked their liquor licenses while they professed ignorance about organized crime that ran the bars and held sway over gay and lesbian lives.

In Atlanta, members of the gay community faced open hostility from all fronts: the Church, the newspaper, the police. They were confined to a few dark, depressing places where they nudged one another on the knee to gauge mutual interest. When the police raided even those places, they were forced to the sidewalks of Peachtree Road again, or to Piedmont Park. They contorted their faces to avoid any expression of desire, had to feign interest in the opposite sex, had to laugh when someone threw the word fag in their face, had to watch the people that passed for a hint of mutual recognition.

They claimed Piedmont Park as their front yard, the Strip as their home. Atlanta’s version of Greenwich Village or Haight-Ashbury, the Strip neighborhood on Peachtree Street was the center of hippie decadence and to some a symbol of Atlanta’s decay, with its grand old houses that emptied out in hysteric fits of white flight. Those who abandoned the area likened the city to ruins, but gays and lesbians streamed in from places like Sumter, South Carolina, and Opp, Alabama, and Soddy-Daisy, Tennessee, and fashioned an oasis. All the animals emerged from the woods to drink from the same pool: glittery drag queens and unapologetically effeminate men, butch women in leather jackets, beautiful athletic gay men with flowing beards and beautiful gay women with flowing hair and painted faces. The Strip pulsed with the energy of a budding gay community, and Atlanta’s nearby gay nightclubs grew bold and dense with newly minted queers who matured in ways forbidden at home, as they experimented with their very identity. They stumbled through the usual mating rituals like kissing, dancing, and dating. They expanded their minds with LSD, speed, marijuana, or plain old alcohol. They learned about themselves and skewered the hostile outside world through the humor and satire of Atlanta’s sub-rosa drag scene.

Police still raided the gay clubs. They cruised Piedmont Park to clear it of “sex perverts.” They would drive by, then circle back with a camera to intimidate people from standing on public sidewalks. When the Stonewall Inn in New York City erupted in a riot in June 1969, the police probably had no idea that it could spread to Atlanta — but a year after the Christopher Street rebellion, when some 20,000 marched in New York and another 5,000 marched in San Francisco, a handful of Atlanta’s gays and lesbians gathered in Piedmont Park. They banded together as the Gay Liberation Front, and handed out leaflets from a table during the spring arts festival. They couldn’t march, they decided; there just weren’t enough of them to avoid looking like a punch line. People were still afraid they would lose their jobs, their families, and their lives if they came out in public. Some didn’t care anymore, and came out anyway. They handed out flyers, talked to straight passersby, and drew pained glances and awkward stares.

***

Mayor Sam Massell had let his jet-black hair grow long, and he told the police to leave the hippies and drag queens alone. But he saw himself as a crime-fighter, and with the blessing of Georgia’s governor-elect, Jimmy Carter, Massell authorized a 64-man police station on the Strip. He had it painted pink and dubbed it the Pig Pen. A thousand people were arrested within the first few months the Pig Pen was open, and the hippies and queers and bikers who lived on the Strip fought back in a hail of bottles and firebombs.

Massell disbanded the station, but Atlanta police wouldn’t leave the Strip alone. They took aim at Club Centaur, a club that featured go-go dancing in the afternoon and nightly drag shows by Phyllis Killer and Diamond Lil, who jammed with her live band. Phyllis performed in long blond curls and swung an 18-foot feather boa as a jump rope while she threw lollipops from the stage. The rowdy crowd called the Centaur home; the police called it a front for the mob. They arrested a woman near the club and raided nearby apartments looking for guns and drugs and prostitutes. The neighborhood rioted, and in a cloud of tear gas the cops arrested 26 people. In November of 1970, Sam Massell ordered the Centaur shut down.

Old Atlanta cheered him on. It believed that the Strip crowd had changed from flower children to sidewalk commandos and punks and freaks. Few of them understood that their old Atlanta was gone forever.

The Strip descended into chaos, and its people moved on — north into Midtown and Buckhead, east to Little Five Points, and northeast along Cheshire Bridge Road. They took their fight with them. The unpredictable and unknowable borders of a police state had kept them pinned under glass, but they began to rap against it. They knew how far they had been pushed and they began to push back. They organized. They prepared for war.

The police stayed at their heels. They knew why gays and lesbians came to the city and flocked to Piedmont Park, especially in spring, when the dogwoods painted the green with white and pink petals, when the sweetgum trees began to build their prickly seedpods. They kept arresting gays and lesbians — for loitering, for jaywalking, for disturbing the peace. They hunted them. They were easy prey.

Excerpted from A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution by Martin Padgett. Copyright © 2021 by Martin Padgett. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Header image: Alan Orton, performing as Lavita Allen. Photo courtesy Susan W. Raines.

Martin Padgett earned his MFA in narrative nonfiction writing from the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and was named a 2019 Lambda Literary Fellow. He is a Ph.D. student at Georgia State University. He wrote this Bitter Southerner story about Leslie Jordan. Marty lives in Atlanta and Pensacola Beach with his husband, their cat, and an overflowing file of future story ideas. He will forever be #TeamKatya.