One Texas-educated writer reveals some gaps in her schooling and wonders what it might look like if children were taught to think critically instead of seeing themselves as kings of the wild frontier.

by Sarah Enelow-Snyder

Back in 1994, I couldn’t wait for seventh grade to begin, because the fabled yearlong class on Texas history was finally here. Nowhere else in the country was there a preteen this excited about a history class.

My excitement had less to do with loving school, and everything to do with a rite of passage. This class would give me the knowledge and the credentials to become a real Texan, just in time for me to hit my teenage years. Plus, it was going to be fun. Our state history was so action-packed, so cinematic, it was unlike any other in the country. In fact, we were our own country for a while. We were heroes. All we did was win.

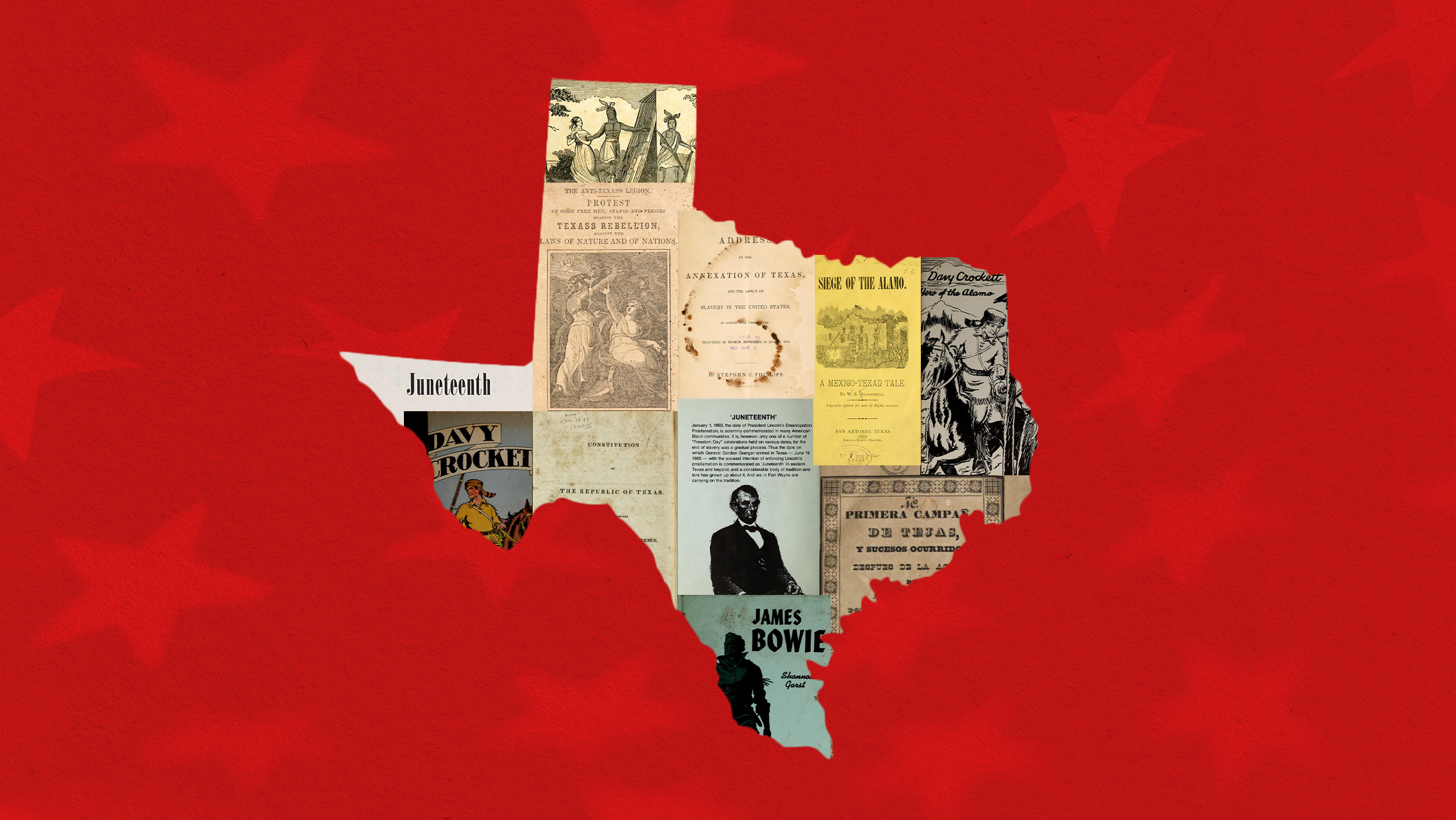

That year my class went on a field trip to the Alamo in San Antonio, just two hours south of our school in Austin. There we watched a booming-loud IMAX film about the 1836 Battle of the Alamo, starring famous Texas defenders like Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, and Jim Bowie, of Bowie-knife fame, fighting off the Mexican army as horses leaped over our heads. We toured the old Spanish mission and went home with keychains and postcards. And we remembered the Alamo, just as we’d been told to do.

When we left the Alamo all those years ago, I didn’t quite understand that the Battle of the Alamo had been a colossal defeat for the Texas defenders. The way we talked about it, with such pride, made it seem like we’d come out on top. I also didn’t realize that the Republic of Texas only lasted for nine years, although I must have been quizzed on those dates at some point. The honor we bestowed on that era made it feel like decades upon decades.

Here’s another bitter pill I swallowed only after moving out of state: that the Republic of Texas was formed in part to maintain slavery. Mexico moved toward abolition when Texas was still part of the country, and then Texas seceded, ensuring slaveholders that those in bondage would remain so. By 1860, more than 30% of the state’s population was enslaved. There was even an underground railroad leading from Texas down to Mexico.

When it came to slavery, my teachers put our state in a vague but flattering light. Texas wasn’t really part of the South, but it kind of was, like a fringe member of the Confederacy. It had slavery, but not to the same degree as a notorious place like Mississippi. Plantations, whites-only lunch counters, and lynchings mostly happened somewhere else, farther east. Having grown up in a rural white community in Texas, I never even learned about Juneteenth until I lived in New York City.

And so, as an adult, I realized I knew nothing about Texas’ Black history. As a once-Texan and a biracial Black person, this was concerning, and frankly, I felt like an idiot.

Though I no longer have my Texas textbooks, I’d be willing to bet that some of the aforementioned Black history facts were indeed mentioned there. But how much weight were they given? Did my teachers gloss over them, or skip them entirely? Did we go on field trips that made Black history come alive? Did we write essays that strayed from the triumphant Western-frontier narrative?

I recently asked a few old friends if their memories of learning Texas history, in such epic grandeur, were similar to mine. One responded, “It wouldn't hurt to find a balance between knowing the state’s history and treating it like ‘The Iliad.’”

In June, Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed a bill that addresses how we tell stories in public school classrooms. HB 3979 bans a set of teaching practices that fall under something called critical race theory, which has already been prohibited in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, Idaho, and Florida, and is on the docket in additional states.

Some use the phrase “critical race theory” as a catchall for any liberal-led discussion about race, but its definition is more specific. Critical race theory began in the legal academy in the 1970s to examine systemic racism in law and public policy. The premise was that the law can exacerbate racial inequality but also be used to achieve equality and emancipation, and these concepts spread to other areas of scholarship. According to the American Bar Association:

“CRT recognizes that racism is not a bygone relic of the past. Instead, it acknowledges that the legacy of slavery, segregation, and the imposition of second-class citizenship on Black Americans and other people of color continue to permeate the social fabric of this nation.”

Many opponents of critical race theory say that it unfairly blames white people for societal ills; that it stokes racial division; that we should be colorblind instead; and that slavery does not affect anyone living today.

The counterarguments are that we should learn about white privilege; that racism itself creates division; that colorblindness erases the breadth and diversity of history; and that slavery birthed segregation, mass incarceration, and other modern-day forms of racial inequality.

My classes back in Texas relied heavily on textbooks, but that’s changed in recent decades, said Kim Denning-Knapp, a member of the anti-racist group Educators in Solidarity. (She’s also an assistant professor at the university level, but cannot speak on behalf of her institution on this matter.) These days, students spend less time reading from a textbook and more time analyzing primary sources, thinking critically, forming their own interpretations and arguments, and communicating those thoughts to one another. That critical thinking about American history naturally leads students to examine systemic racism, said Denning-Knapp, who taught at McNeil High School in Round Rock, Texas, for 15 years. “Some people call that critical race theory, but it really is just doing history. It’s thinking like a historian.”

Texas’ ban on critical race theory prohibits teachers from causing anyone to feel guilt on the basis of race — for example, if a student feels bad about their white privilege. They also cannot award course credit for political activism, suggest that colorblindness is impossible or unwise, say that anyone bears responsibility for past actions of members of the same race, or say that racism is endemic to the United States rather than a deviation from its founding principles. This bill, which never actually uses the phrase “critical race theory,” ensures that Texas kids will grow up with the same incomplete, white-centric history that I did, carefully avoiding the touchy yet omnipresent topic of race.

“You’ve got to stop worrying about what you think people are doing to you and prepare to live in a market economy,” said John Sibley Butler, a scholar with 1776 Unites, which has published numerous articles in opposition to critical race theory. He’s also a professor at the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin. “What we’re trying to do is cut through all the race stuff. America is about markets, about opportunity structures.” The models for individuals to succeed in America are already in place, he said.

That ethos is familiar to me, and when I was a kid, it felt empowering, the idea that through hard work, we are the masters of our own destinies. The allure of that idea may explain why our conversation drifted away from the classroom and toward the broader idea of success.

The arguments against critical race theory feel quite old to me. Thirty years ago, we were taught that colorblindness was ideal and that affirmative action was reverse-racist against white people. I wrote my high school thesis on affirmative action’s flaws, despite the fact that I got into college in part through a legacy on the white side of my family. I mentioned this in my paper because my father urged me to be honest with myself. None of my teachers asked me to think critically about my cognitive dissonance. In fact they praised my work, agreed with the premise that affirmative action was a mostly bad thing, and had me graduate with honors.

Being labeled a racist can bring consequences, like being fired or shunned, and I can understand that this is scary for some people. When I first got to college in upstate New York, I wrote an opinion piece for the school paper, backed by absolutely no research, about how slavery ended ages ago and racism was a thing of the past — an old trope I’d heard many times at school and eventually internalized. At this point in my life, I had never heard the phrase “Great Migration,” by which 6 million Black people fled the South because slavery had paved the way for Jim Crow. A fellow student wrote to the paper to say as much and call me out. At first I recoiled from the sting of public criticism, but I couldn’t deny the new information being brought to my attention. The whole experience broadened my view, as did my interactions with other students as I settled into my freshman year.

I began reading up on Black history, and finally started asking my parents questions I’d never thought to ask them before — questions about history, but also about us. Why did the Texas public school system expel my brother for getting into fights instead of teaching his classmates that their behavior — like calling him a n----- and taunting him regularly — was unacceptable? As much as I had been looking forward to Texas history, I learned by the end of seventh grade that I didn’t fit in with the other proud Texas kids. Girls started calling me names, mostly directed at my tight, frizzy, dark brown curls: dirty, rat’s nest, Sideshow Bob, Don King. They yanked my hair and pushed me onto the ground. I left school voluntarily at the end of seventh grade so I could be home-schooled bully-free for eighth grade, and then go to the same private high school as my brother for a fresh start. Why didn’t anyone at the public school encourage me to stay? Why did the school turn its back on us?

My parents were deeply frustrated by the school system, and they knew those kids were doing what they were taught. They learned to say n----- from their parents and other adults in their lives. They learned from magazines and television that blond hair and blue eyes were beautiful, and that Black features were ugly. They learned from their teachers that white Texans were heroes, and Black Texans didn’t even exist.

In addition to banning critical race theory, in June, Texas’ governor signed into law the 1836 Project, which he said “promotes patriotic education about Texas and ensures that the generations to come understand Texas values.” The name mirrors that of The 1619 Project, a New York Times Magazine initiative that examines slavery’s legacy and is taught in some schools. Under HB 3979, curriculums such as The 1619 Project are prohibited in Texas schools.

On top of that, HB 3979 is going to a special session to increase its restrictions on teachers.

I asked Denning-Knapp how teachers could possibly discuss systemic racism with the ban in place. That’s the million-dollar question, she said, adding that avoiding the topic completely is unrealistic for teachers. When it comes to the formation of the Republic of Texas, “the historical record is clear that slavery played a role, and primary sources don’t lie,” she said. “If I were still in the [precollege] classroom today, I would hope that my school and my school district would have my back.”

But there is hope in the kids themselves and their inquiring minds. I didn’t begin to do any serious inquiry until college, but younger generations are different. Students will have conversations about systemic racism no matter what, said Denning-Knapp, even if teachers try to avoid it during class. Students will talk between classes, at lunch, and off campus, and unlike me back in the ’90s, they have the internet at their fingertips to research anything they want. They have skits and explainers about racism on TikTok, which is as unregulated as any social media platform, and tailored to a user’s preferences, but still, it’s putting the issue into the palms of their hands. “In middle school they talk about racism, they talk about sexism, and these conversations are not being driven by teachers,” Denning-Knapp said.

In the case of her 13-year-old son, Denning-Knapp sees him digging into historical topics on his own, and moreover, he challenges the validity of what he reads to determine for himself how reliable that information is. “He knows when he’s being fed something that is a half-truth,” she said. “If you don’t teach inclusive history, kids learn to distrust their schools. They learn to distrust the adults in their lives. They learn to distrust their state and national leadership.”

Southern states may be leading the charge against inclusive storytelling, but other parts of the country are pushing for these restrictions as well. In order for any state to tell a fuller version of history, we would have to assert that we were sometimes on the wrong side of it. Kids are still very young. They may have smartphones, but they don’t always know what’s being left unsaid, and not all kids challenge what their teachers present. At least for now, they need us to guide them, and to show that learning the whole truth is the greatest rite of passage there is.

Sarah Enelow-Snyder is a New Jersey-based freelance writer who grew up in Spicewood, Texas. Her essay about being a Black barrel racer appears in the forthcoming anthology Horse Girls from Harper Perennial. For The Bitter Southerner, she's written about the rapid growth of Austin, Texas.