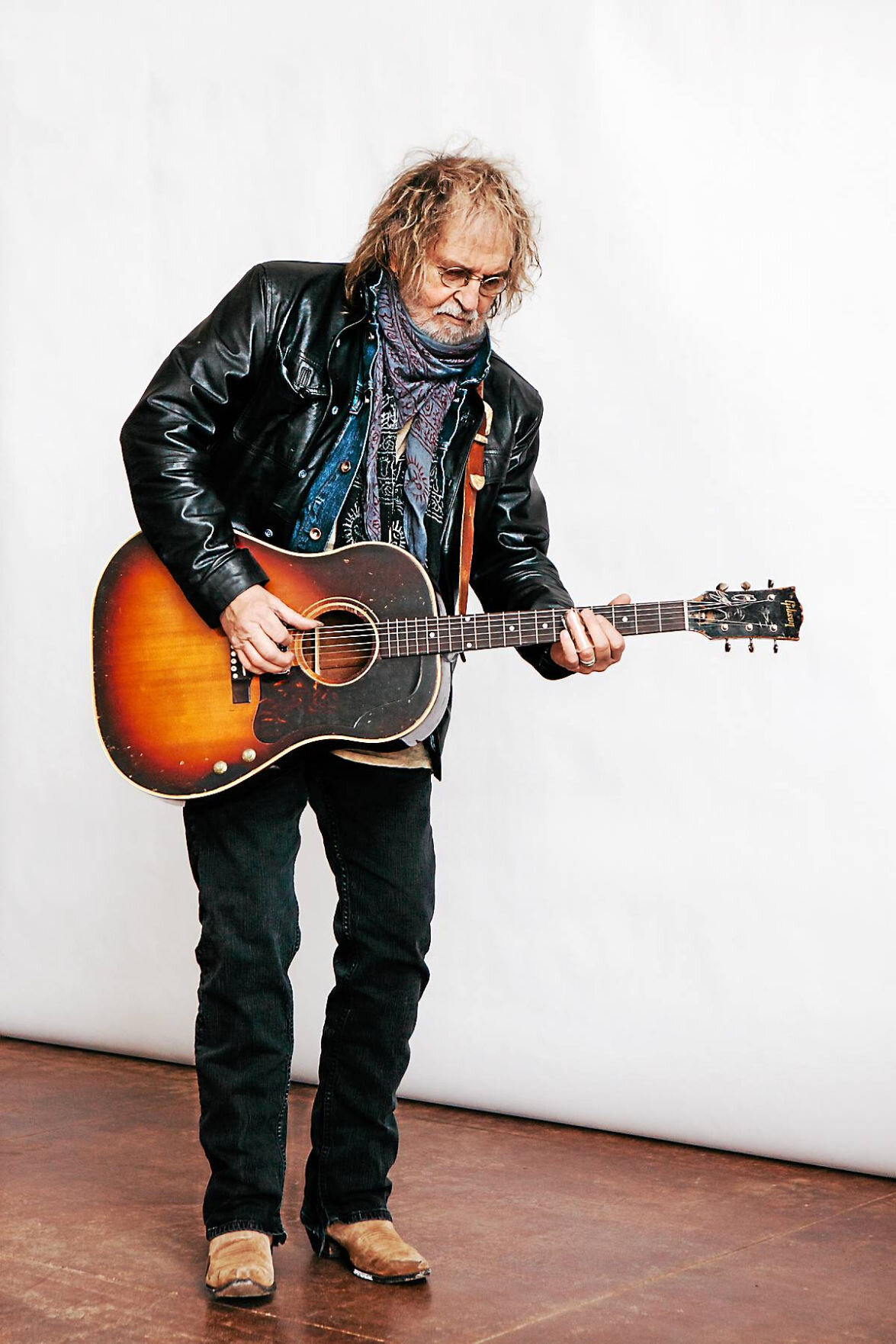

Long considered a “songwriter’s songwriter,” Ray Wylie Hubbard taps into the Southern music tradition of balancing the sacred and profane. In the three decades since he hit rock bottom, his music, career, and perspective have been reborn. Hubbard’s debut performance on Austin City Limits will air on Saturday, Jan. 23, on PBS.

By Peter G. AuBuchon & Victor J. Malatesta

Some are here working on a passage to Heaven

And others, they can’t carry that load

A few are left singing the blues on Purgatory Road

—

“Purgatory Road,” Ray Wylie Hubbard

“My dad got his degree in English literature from, what was, at the time, Oklahoma A&M,” Ray Wylie Hubbard recalled during a Zoom interview in December. “He didn’t read me The Three Little Pigs. He’d read me ‘The Raven’ or The Tale of Two Cities and say, ‘We’ll discuss it at dinner.’ So he kept me into literature and the magic of words, of putting words together … So, when I was into folk music, the lyrics were really important to me, and still are.”

Born in Soper, Oklahoma, on Nov. 13, 1946, the only child of an English teacher father and a strong-willed mother, Hubbard lived near both sets of grandparents, until moving to a suburb of Dallas just before starting fourth grade. In his autobiography, a life … well, lived, Hubbard writes about three bargains he made with God, full of the guilt, fear, and faith of his Pentecostal religious upbringing.

Hubbard made his first bargain after he hit his cousin in the head with a rock. As Hubbard recalls in his autobiography, “blood spurted everywhere. He started screaming and crying and running around in circles and then fell to the ground and started rolling around.” Only 5 years old, young Ray promised he would go to church “every Sunday for five years without missing a single day” if God would allow his cousin to live. It seems as though he kept that promise.

The second bargain happened on the day 6-year-old Hubbard was baptized. He wrote about the preacher “praying … and screaming to high heaven for the Lord to save these wretched souls in southeastern Oklahoma” and of being underwater in the baptismal tank and needing to pee so bad it hurt. Once again, Hubbard fervently prayed to God, pleading with the Lord to not let him pee in the baptismal tank. Hubbard was able to hold his bladder through this ordeal and ended up feeling obligated to God once again. As Hubbard wrote of this account 63 years later, he sometimes wished he had just gone ahead and peed.

The third bargain with God happened while Hubbard was in eighth grade and a medical exam revealed that his testicles had not yet dropped. Facing the risk of a delicate, and presumed painful, surgery, a young Hubbard again prayed to God. This time, he promised God, on the night before the scheduled surgery, that “if He would just let these things drop, I will always be good.” Miraculously, God answered Hubbard’s prayers. He thanked God from the bottom of his heart and swore he would be “good for the rest of his life.” Let’s just say it took Hubbard a few decades before he took up his end of the bargain.

Hubbard remembers an adolescence marked by recurring loneliness, an “awful” ninth-grade year, and social isolation and ostracism in 10th grade when he lost his peer group to a different high school and was seen as the “new hillbilly kid.” Eventually, Hubbard found acceptance with nonconformist classmates, and he had his first beer. Around that time, he saw a soon-to-be bandmate finger-pick songs on his guitar. “I had seen the light,” Hubbard recalls. But, in 11th grade, he also began his habit of drinking a case of beer alone every Friday night.

Jerry Jeff Walker (left), Ray Wylie Hubbard, and Terry Ware in Dallas circa 1975. Photo courtesy of Ray Wylie Hubbard.

Hubbard got his start playing folk music at age 17 after answering an ad on his high school bulletin board to perform at a rustic resort in Red River, New Mexico. He and two friends stayed in the back of the resort, doing kitchen duties during the day and playing music at night. The trio eventually became the band, “Three Faces West,” and they played in Colorado and Texas.

In the early 1970s, his next band, Ray Wylie Hubbard & The Cowboy Twinkies, was born. Performing in countless honky–tonks and dance halls throughout the South, Hubbard became one of the original Outlaw Country performers of the Texas music scene. In 1973, Jerry Jeff Walker recorded Hubbard’s funny social commentary of a song, “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother,” and Hubbard had his first taste of commercial success.

Frustration with two separate record producers, Bob Johnston in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and Michael Brovsky in Nashville, Tennessee, and the heartbreaking ruination of Hubbard’s first album by Brovsky led to his hospitalization at the age of 29 due to alcohol and drug abuse. More career frustration followed.

“We were playing and selling out the same venues as Willie [Nelson and] Jerry Jeff … but couldn’t get a record deal,” Hubbard said.

Hubbard’s 30s were marked by multiple losses that sent him on a tailspin. His first marriage ended in divorce and both of his parents died. His alcohol and cocaine addictions reached the point of out-of-control behavior, blackouts, hitting the proverbial “rock bottom,” and suicidal contemplation.

I used to take comfort from

the loneliness with whiskey

It tore up my soul

and it turned against me

I stood at the fire with my hand on a knife

I didn’t have a prayer

No, I didn’t have a prayer to save my life

— “Didn’t Have a Prayer,” Ray Wylie Hubbard

Texas Blues master Stevie Ray Vaughan took Hubbard, who was 41 at the time, to his first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and everything began to change — mentally, spiritually, and musically.

“I had had all the fun I could stand,” Hubbard told us. “It got to a point where it wasn’t fun anymore, it was dangerous. So I got in recovery with Stevie Ray, and he was the first cat I saw that had gotten clean and sober and didn’t turn into a square. You know he didn’t end up on the 700 Club. He still had a bite and fire about him. Because of that, I got a little hope from Stevie Ray that, you know, maybe if I quit drinking and drugging up, that I wouldn’t turn into a square.”

‘Our Fears Are Like Dragons’

By the time he entered AA, Hubbard says he considered himself “a pretty militant agnostic.” In order to save his life, however, he adhered to the 12 steps and turned himself over to a higher power. An influential AA member even convinced Hubbard to get down on his knees and pray. That moment ended up in his song, “Prayer.”

It’s likely that God don’t need to hear my prayers

I just need to hear me praying

Hubbard said that his acceptance of other AA members as a “power greater” than himself helped him abstain from alcohol. Hubbard relied on this fellowship, worked on the 12 Steps of AA, and experienced what AA describes as a “spiritual awakening.” Not only was his life saved, he met the love of his life, Judy Stone, who became his wife and business manager.

“If it wasn’t for Judy, I would have everything I own in a shoebox and be looking for a happy hour gig,” Hubbard said. “Judy says, ‘Write what you want to write, and make the records you want to make, and I’ll try to sell the damn things.’”

Hubbard’s musical rebirth began soon after his spiritual one: Inspired by Rainer Maria Rilke’s book, Letters to a Young Poet, and encouraged by a friend from AA, Hubbard took guitar lessons at age 42 and learned how to finger-pick.

“The Messenger,” the first song featuring his new-found guitar skill, is an important song for Hubbard. He played it to his unborn son, it is the first song presented in his autobiography, it is the only song that Hubbard has recorded on three separate albums, and it is one of three songs Hubbard chose to sing at his Grand Ole Opry debut in 2019.

Now I have a mission and a small code of honor

To stand and deliver by whatever measures

And the message I give ya, I got from this old poet, Rilke

He said, “Our fears are like dragons guarding our most

precious treasures”

— “The Messenger,” Ray Wylie Hubbard (1999)

Hubbard had overcome his fear of embarrassment at taking music lessons later in life and reached one of his most precious treasures: becoming a proficient blues guitarist.

More importantly, the song is a mission statement. As Hubbard wrote in his book, he decided to write songs “to improve people’s lives whether it is making them smile, giving them a groove to dance to, inspiring them to sing along, or maybe create some lyrics that can make them forget for a few moments that some darkness has swooped down on them and got them troubled.”

Hubbard decided to write songs “to improve people’s lives whether it is making them smile, giving them a groove to dance to, inspiring them to sing along or maybe create some lyrics that can make them forget for a few moments that some darkness has swooped down on them and got them troubled.”

From our interview, Hubbard added:

“I got clean and sober at 41, and at 42 I had this really weird, rough gig. I came home and I got quiet and I just kind of made this conscious decision or prayer that I was going to write songs, not to see what I could get, but to see what I could contribute.

“I wasn’t going to write songs and try to get Garth Brooks or Tim McGraw to record them. And I wasn’t going to write songs for a publishing company where I had to give them 12 songs a year … Like, I’d do a line and they’d smile, or I’d do a groove and they’d feel that groove, or I’d name drop somebody and they’d go check out and see who that person was. So that’s really the way I still go about it.”

Hubbard’s search for spirituality began with an outright rejection of traditional religious dogma and its practices.

“I didn’t have any idea what spirituality was, but I knew that I wouldn’t, I couldn’t, follow any religion because of the history of that religion. You know, like some of the atrocities that occurred in the name of religion; and that it seemed that a lot of religions tried to force their beliefs on someone, and I couldn’t get behind that,” Hubbard said in our interview.

Hubbard refers to himself now as a “spiritual mongrel,” poring over various religious texts and leading him to reference Buddhism, Hinduism, Native American folklore, the book of Revelation, Hoodoo, reincarnation, and enlightenment in his songs.

Hubbard gets away from an “all or none” view of morality. He acknowledges a continuum of goodness to evil and the imperfect, or “dark side,” of each of us.

“You know, the thing is, is that the devil is a pretty interesting character, and I’d rather write about Attila the Hun than Bambi — you know what I mean? Take the song, ‘Lucifer and the Fallen Angels’ … I enjoy having the freedom to write that song, knowing that nobody else is ever gonna record it. And it’s probably not going to get played on radio stations.

“But it’s a cool song, and you know, I get to say some things in it through the devil speaking that maybe I shouldn’t say. Like in the song, ‘Conversation With the Devil,’ I get to say these little punchlines, that well, I didn’t say that, the devil said that, you know, like about the ‘right wing conservative’ Nashville record executives. So with all my songs, it’s just finding a tool to say something, whether it’s me, the devil, or a little animal saying it.”

Hubbard told us how he began working gratitude into his songwriting process. “Here’s the thing, right after I write a song, I’ll play it and I’ll play it again and I’ll go, ‘OK, that’s done. And then all of a sudden I’ll just go, ‘Thanks.’ It’s just a little ritual that I have. I have no idea who I’m thanking or what, but it doesn’t make a difference. I just don’t want them to shut that door — you know, whoever, whatever it is. So keep ‘em happy. I’m grateful for these songs, these little things that weren’t here before.”

“You know, I’m not that talented and not that lucky. I mean I know a little bit about how to write some songs, but that’s pretty much it. So it’s inspiring even for me that even as an old cat, good things are still happening for me.”

His gratitude extends beyond his songwriting to the arc of his career that has blossomed since he has been in recovery. From 1992-2020, Hubbard put out 13 studio albums and one live album. He has appeared on all of the late night television shows and has had a top 10 Hot Country co-write with country music star Eric Church. He also was inducted into the Texas Heritage Songwriters’ Association Hall of Fame, received a songwriting award from SESAC, appeared at the Grand Ole Opry, and received critical acclaim from Ringo Starr. By all accounts, Hubbard is a quintessential Texas singer-songwriter, standing side-by-side with artists like Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, and Billy Joe Shaver.

“I’m an old cat, you know, and all of a sudden I look around and ever since I turned 60, amazing things have happened. I look back at my 20s and 30s and I just kinda drank beer, peed, did drugs, hurt people, played some gigs, and wrote some stuff. But once I got clean and sober, things have been validated for me. … You know, I’m not that talented and not that lucky. I mean, I know a little bit about how to write some songs, but that’s pretty much it. So, it’s inspiring even for me that, even as an old cat, good things are still happening for me.”

We asked Hubbard if he could explain it further:

“I can’t, you know. I heard this old guy in Dallas say that there was a ‘power in the universe that honors our faith in it — a creative intelligence underlying the material world in life as we know it.’ He said if we come to believe in this power, it will honor our faith in it. It won’t give us the lottery numbers or it won’t make our car payment, but we can call on this power to give us courage if we’re in a scary situation or to call on it to give us the opportunity to tell the truth or lie. So that’s my spirituality in a nutshell. And, you know, there are some days when I don’t believe that at all … but the days that I do, I have really good days, you know, and I get songs.”

Hubbard’s music has a way of expressing the pain and tension so many of us feel inside of ourselves, about the South, and our deeply divided country and world. After the mass shooting at the 2017 Route 91 Harvest music festival in Las Vegas and Tom Petty’s death the next day, Hubbard wrote the song, “Rock Gods.”

I stood in disbelief wonderin' when the madness is gonna be done …

Seems the whole world is broken and crying

It is more than prayers we’re needing

We’re all on a cross, alone and bleeding

Hubbard may not know all the answers to his spiritual quandaries, but he wants us to accompany him on his journey down Purgatory Road. When we asked Hubbard if he could sum up his belief system, he said, “I finally figured out that it really doesn’t make any difference what I believe to anybody else just as long as I keep my side of the street clean and do the next right thing.”

Peter G. AuBuchon received his Ph.D. in clinical psychology from the University of Georgia in 1986. He is currently in private practice in the Philadelphia area and has numerous publications in scientific journals and professional books. Besides being a lover of blues, roots, and "country music that's real," he is happily married with two daughters who are both pursuing careers in psychology, and is an avid tennis player and cook. Having grown up in Florida, AuBuchon still has "sand in his shoes" and identifies as a Southerner.

Victor J. Malatesta is a clinical psychologist who practices in West Chester and Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. He is also a weekend country-rock musician who had the good fortune to live for 10 years in Athens/Nicholson, Georgia, and Charleston/Folly Beach, South Carolina, during graduate school and early career. He loved the South so much that he married a smart and beautiful Georgia woman who was a nurse and a musician. Together, they performed in various honky-tonks and bars throughout the South. He convinced her to move north in 1983, telling her that they'd only be there a few years. She's never forgiven him. Their two beautiful children, along with regular trips South to see family and friends, have helped to ease the pain.