The Atlanta Braves won the World Series. Ed Southern writes about the team that he loves and the long overdue need for its name to change: How about the Atlanta Hammers?

By Ed Southern

The Atlanta Braves winning the World Series the year that Henry Aaron died is a fairy tale, a jubilation for all of us throughout “Braves Country.” They lost their best player to injury in July. They had a losing record going into August. To see the Braves come back from that to win it all is stunning and stirring and joyful.

To see the Atlanta Hammers do it, though, would have been even better.

Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron was the Braves’ linchpin: the franchise’s best player not only when they moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta in 1966, but still today. He’s in most every discussion of the greatest players of all time. His consent was key to the Braves’ move South. The city had to convince him he could live in Georgia with dignity, that he was returning to a different South than the one baseball had helped him escape.

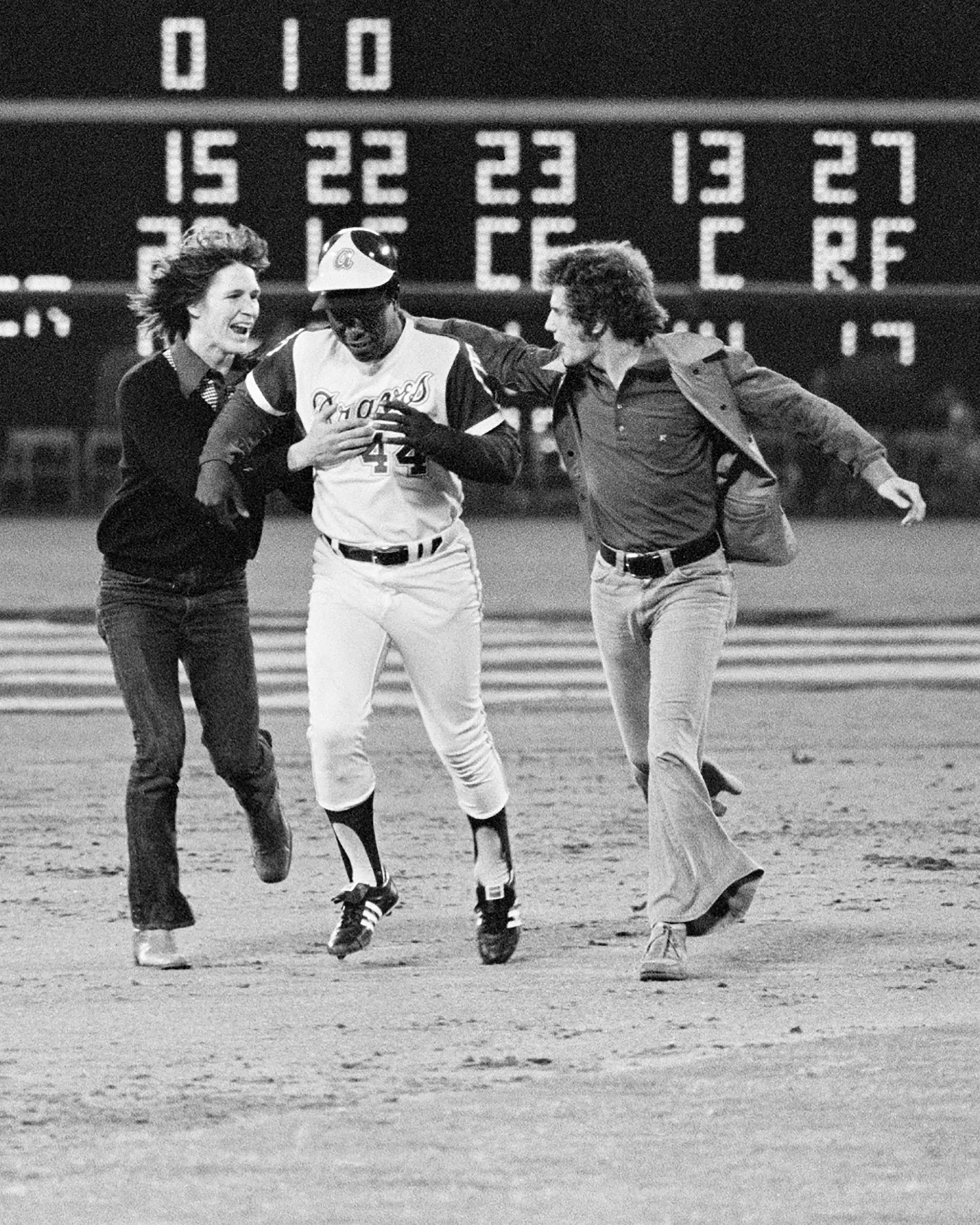

Atlanta might have pitched itself to the world as “the City Too Busy to Hate,” but Aaron, an Alabama native, surely knew better. He — and the FBI — took seriously the death threats that came as he closed in on Babe Ruth’s record 714 home runs. When he hit his 715th on April 8, 1974, at Atlanta Stadium, he circled the bases warily, expecting with every step to hear and feel the shot meant to kill him.

That home-run trot was the Atlanta Braves’ first and, until the 1990s, only moment of triumph. Every time it re-aired, we cheered it and ourselves, nice white fans cheering a Black man’s success in the New South. We cheered the two young white men who stormed the field and ran down Aaron on the base path, to pat his back and shake his hand. We cheered it as a sign of unity and interracial joy, and ignored what it was: white men inserting themselves into a Black man’s greatest victory, claiming for themselves some piece of the spotlight that should have been his alone.

In my book Fight Songs: A Story of Love and Sports in a Complicated South, I wrote a little about the Atlanta Braves, what they mean to me, what they mean and could mean to the South. I wrote about how a Braves game in Atlanta could offer “a wider panorama of the contemporary South than Lookout Mountain on the clearest day.” I wrote about “the shock of TBS,” and of Atlanta itself, I felt as a child: “the shock that a Major League Baseball team and a ‘Superstation’ could exist in the South, the South I was in and of, the South I already understood to be set apart. ... ”

I wrote about how the Braves could be the South’s new flag, a connector we could use to stand against the finishing blows of the Bulldozer Revolution and the kitschification of the best of our traditional ways. They could be a symbol of Southernness open to all — all of us in and of and in love with the South.

Except that “Braves Country” first was Indian Country, and still is home to thousands of Native people: Lumbee, Catawba, Haliwa-Saponi, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, Cherokee.

During the Black Lives Matter movement in the summer of 2020, the long, low-volume discussion of representation in team names and mascots became louder and more insistent. The Cleveland Indians, with their cartoonish “Chief Wahoo” mascot and logo, began a process that has led to their becoming the Cleveland Guardians in 2022. The Washington, D.C., NFL franchise finally, finally, dropped its team name, an unambiguous slur with truly vile historic connotations.

The Atlanta Braves, though, said they’d stay the Braves, arguing that they used no cartoonish representations and that “Braves” is not a slur. They also pointed to their long history of good relations with the nearest federally recognized Native tribe, the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians (EBCI), whose rolls include a number of Braves fans.

“I think the Eastern Band support of the Braves goes back to the pregaming days when all we had to survive on was kitschy tourism,” Cherokee writer Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle told me by email.

Annette Clapsaddle, photographed by Mallory Cash

Clapsaddle is the author of the 2020 novel Even As We Breathe. She grew up and still lives in the Qualla Boundary, the EBCI land in North Carolina’s Smoky Mountains, closer to Atlanta than to Raleigh.

Clapsaddle’s grandfather, before he was elected Principal Chief of the Eastern Band in the 1950s, was a 6-foot-6-inch, 350-pound ex-Marine who supported his family through the Depression as a champion pro wrestler, calling himself “Chief Saunooke.” Her parents owned and operated Saunooke’s Mill, a gift shop at the Qualla Boundary’s entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where their customers were mostly white flatlander tourists.

“My family put me through college on colorful headdresses and beaded moccasins. My grandfather promoted his wrestling using the cheesiest of faux-Indian costumes. So when we could latch onto the Braves for marketing, we did,” Clapsaddle said. “I grew up loving the Braves as a kid, when Dale Murphy played. Of course I was still in elementary school, so I have a right to change my opinion.

“My biggest problem as an adult EBCI member, with EBCI member children, is the liberty with which fans take the stereotypical imagery. That tomahawk chop is brought out in gyms across North Carolina just as soon as another team notices they are either playing a Cherokee school or their opposition has a Cherokee member. They use it to mock. That is the only evidence I need to believe it is not honoring anyone. Cartoons and caricatures are serving as stand-ins for reality. When that happens, human rights are violated,” she said.

“The name is not the racial slur that the Redskins was, but it really doesn't matter. The main problem is that 99.9% of the world (even America) does not have the counternarratives handy to understand that Native Americans are, one, still alive; two, functioning much like themselves; three, not magical or warlike. Until we can do better with teaching not only Native American history, but also recognizing modern Native voices, we (the collective American sports fan world) have absolutely no right thinking the Braves imagery can fill a role in education, acknowledgement, or honor.”

I can’t help but want to defend the Braves, at least a little. They retired their “Chief Noc-A-Homa” mascot in the 1980s, before they moved into Turner Field, as well as their “Screaming Indian” logo. They created an Atlanta Braves Cultural Committee, with members from the EBCI, “to educate staff and players, ensure any representation of the EBCI is culturally appropriate, and the EBCI’s interests are met moving forward,” according to a July 2020 article in the Cherokee One Feather. When they met the St. Louis Cardinals in the 2019 playoffs, they did not leave foam tomahawks in the seats as they usually do for postseason games, and they reduced their use of the tomahawk chop. The Cardinals’ Ryan Helsley, a member of the Cherokee Nation, had told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that the chop was “a misrepresentation of the Cherokee people … it devalues us.”

Clapsaddle made clear that her opinions are just that — opinions, hers alone — and that “there is no one ‘EBCI voice’ that speaks for everyone.” Many members of the Eastern Band, she told me, remain staunch fans of the Braves, and take no issue with the team name or the tomahawk chop. Harrah’s Cherokee Resort and Casino, located on EBCI land, is a leading Braves sponsor. When Atlanta reached the World Series, EBCI Principal Chief Richard Sneed told the Associated Press, “I’m not offended by somebody waving their arm at a sports game. … At the end of the day, we’ve got bigger issues to deal with.”

As a fan; as a native of the South, Southern by birth and raising, and even name; as a member of what Wright Thompson called “Generation Murph,” who grew up with Dale Murphy and Claudell Washington, Skip Caray and Pete Van Wieren, who remembers where I was when Sid slid home; as a middle-aged white man with all the privilege that accrues: I would not miss the name “Braves” at all.

I would hate it if they changed their script-A logo. I would hate it if they got rid of their red, white, and blue color scheme. I would really hate it if they lost the Waffle House inside their ballpark.

I did hate it when they left Atlanta for the suburbs of Cobb County. I hated not going to Atlanta to see the Braves, not visiting that city, not seeing the gleaming skyscrapers of the New South above the outfield bleachers.

I would hate it if they traded “Braves” for something silly and corporate, test-marketed to meaninglessness. I would miss being able to call them the “Barves” when they screw up.

I would love it, absolutely love it, if they became the Hammers.

The first call to turn the Braves into the Hammers that I can find online is in a February 2013 SB Nation column by baseball writer Rob Neyer. By November 2020, the fan blog Braves Journal had Atlanta Hammers T-shirts for sale, with the red-and-yellow tomahawk across the chest transformed into a claw hammer.

After Aaron’s death in January 2021, the calls reached a crescendo and went mainstream. #AtlantaHammers trended for weeks on social media. Local and national media picked up the story. Fans organized petitions that got thousands of signatures.

Liberty Media Corporation, the conglomerate that owns the franchise, said the Braves would stay the Braves.

They could have changed the name with not just ease but raucous approval. Who could object to honoring Aaron, the team’s greatest-ever player and a thoroughly decent, brave, and humble man who for decades represented the franchise and its city with warmth and grace? Who in “Braves Country” could be all that attached to the name “Braves”?

The Atlanta team name with the deepest roots is the Crackers, the city’s minor league team from 1901 until the Braves arrived in 1966. “Braves” fits Atlanta and the modern South only because it’s a well-traveled transplant from the North. The franchise was born in Boston in 1871, as the Boston Red Stockings. The team went through several nicknames before 1912, when it became the Braves to honor not Native American warriors but its new owner, who had made his fortune in New York City as an apparatchik at Tammany Hall, as rife with Native appropriation as with graft.

The “chop” is not an Atlanta native, either. Braves fans first chopped in 1991. I remember watching the game when it started, spontaneous and scattered, in honor of new Braves outfielder Deion Sanders, who had been a football star for the Florida State Seminoles. Florida State fans had begun their tomahawk chop only in the early 1980s. Atlanta’s chop was dying out after Sanders left, until the team’s marketers revived it with piped-in sound and props.

These are not traditions rooted in baseball’s misty, mystical past, or in the history of Atlanta or the South.

How easy it would have been, how obvious: Keep the motion but replace the chant. Turn the tomahawk chop into the Hammer Drop. Become the Atlanta Hammers.

They did not.

They created the Henry Louis Aaron Fund to increase “access and opportunities in the areas of sports, business, education and social and racial equality,” and gave it $1 million. They brought out the Aaron family before Game 3 of the World Series at Truist Park, and had Aaron’s son, Hank Aaron Jr., throw out the first pitch. They mowed “44,” Aaron’s number, into the outfield grass.

Now the chance might have passed. The “Braves” name and the tomahawk chop have become yet another battlefield in our silly, deadly culture wars; yet another excuse for some white people to feel sorry for themselves, to claim themselves the center of every story. To change the name now, even to honor Aaron, would strike too many as a surrender.

The name and the tomahawk chop are obvious and justified targets, but the earnest critiques when Atlanta won the National League were too often lost amid the posturing and easy scapegoating of the South.

Danders got up. Feelings got hurt. Why have an honest reckoning when you can feel the self-righteous rush of backlash?

The tomahawk chop used to break out only in the late innings, in crucial situations: an Atlanta reliever coming in with the bases loaded and only one out; an Atlanta batter at the plate, runners at the corners and the home team down two runs.

In the 2021 World Series games played at Truist Park, Braves fans chopped early and often. The rallying cry seemed to have slid into a statement of identity, of defiance, of privilege, of juvenile provocation. When the World Series came to Atlanta in 1995, we saw Braves fan Jimmy Carter along the first baseline, rooting for the home team. When the World Series came to Cobb County in 2021, we saw Yankees fan Donald Trump, glassed off in a luxury box, tomahawk chopping with that rictus grin on his face.

Let me admit now, if it’s not too late, that I have chopped, more than once. Somewhere there’s a photo, taken at a Georgia wedding reception, of me holding a Braves foam tomahawk. Let me admit now that to be in the ballpark in the midst of an Atlanta rally, one of 40,000 chanting and chopping, was to experience the powerful sense of community and purpose that spectator sports simulate so well. Let me admit that I chopped with a big smile on my face.

I won’t anymore. I would drive the 10 hours to Atlanta and back for Friday’s championship parade if I could get off work. I would defy the pandemic to stand with all my fellow fans and quarantine after. I will, by God, make it back to Atlanta for a game next season.

I will not chop. I am afraid — not worried, but afraid — that the team I once thought could bring us together, all of us in and of and loving the South, now will help to drive us apart.

This isn’t about being “woke,” whatever that means to you. It’s not about equity, or “justice for all.” It’s not about reparations or land restoration or dismantling any structure, however much that structure’s tumbling, taking us all down with it.

This is simple decency. This is decent manners — not even good manners, only middling. This is neighborliness. This is not being assholes.

This is just a doggone baseball team. This is just a name, a mascot, but this is also one of the stories we tell ourselves and others, to tell ourselves and others who we are. This is telling the story we should have told. This is telling the story we could still.

Ed Southern is the author of Fight Songs: A Story of Love and Sports in a Complicated South, published in September by Blair. His stories and essays have appeared in storySouth, the North Carolina Literary Review, the Asheville Poetry Review, and elsewhere. Since 2008, he has served as executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network. (Photo by Jess Blackstock)