What motivates people who are facing grave illness or death? What keeps the embers of hope alive? One of the toughest jobs out there is the care of patients and families who face what nurses call “the transition.”

By Cindy Miller and Edward Miller | Photographs by John Glenn

It was not your typical high school graduation. The single graduate was in a hospital bed, too weak from chemotherapy to put on her gown. The scene was supportive — flowers and a “Congratulations” sign decorated the room — but subdued. The 18-year-old graduate had ovarian cancer.

Days before, she had wanted to go home for the real graduation at the high school. Her nurses considered multiple contingencies as they gathered the medications and supplies she would need on her brief outing, but she returned to the hospital by midnight without having attended the ceremony. Sadly, she told them she simply didn’t have the energy to go through with it.

Not to be deterred from a healing mission, the nurses worked with the teenager’s family to bring her graduation ceremony to Piedmont Atlanta Hospital.

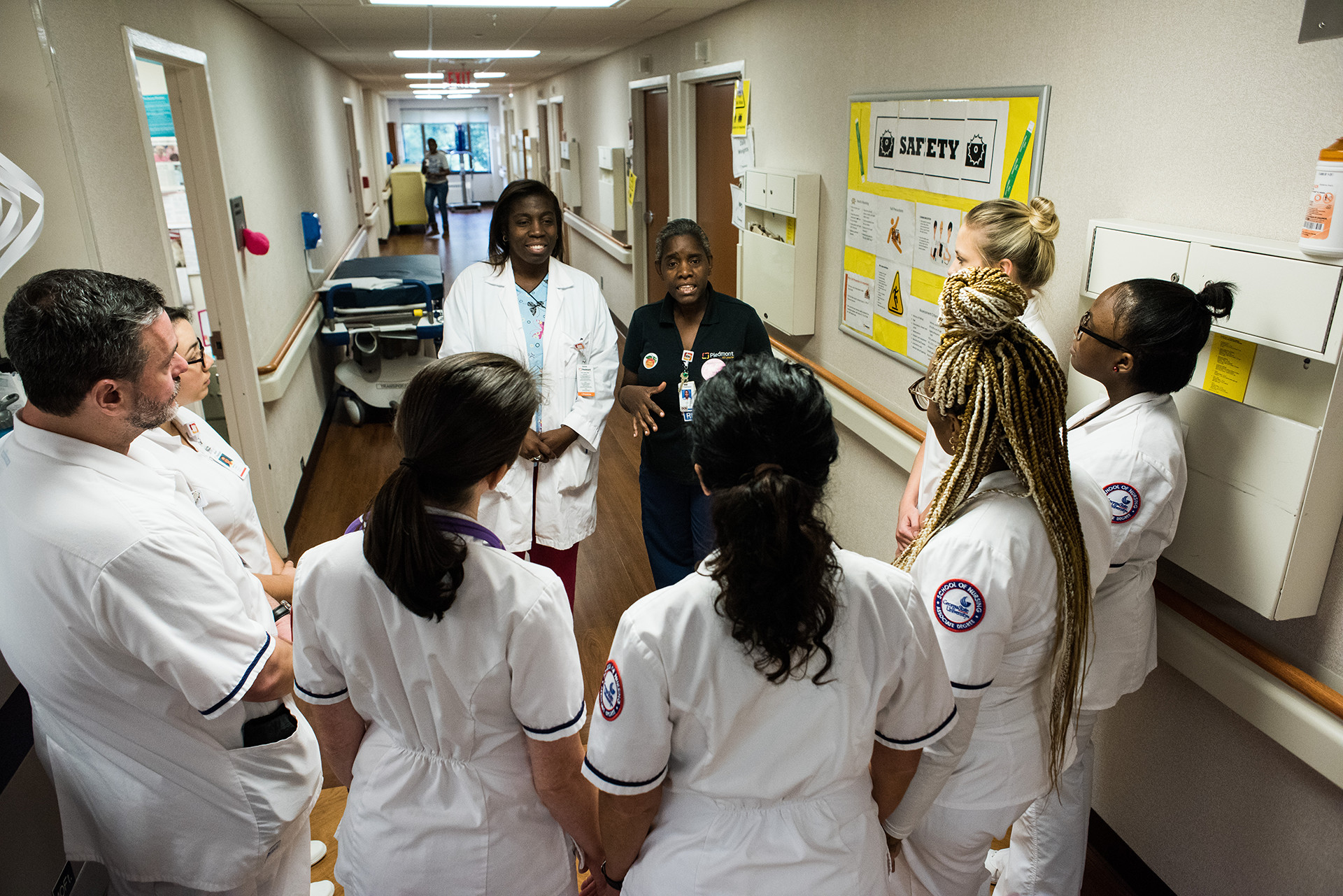

“As nurses, we want to help them be a part of special moments,” says Bobbi Lineham, a nurse in Piedmont Atlanta’s medical/surgical unit. “In these cases, the family focus is on each other. Our focus is on easing their burden.”

Three family members attended, along with the student’s principal, a school administrator, her class president and quite a few nurses. Bobbi videotaped the event for the patient’s mother and a loved one away in the military.

“She appreciated what we had done, but she was weak and it took a lot out of her, so we kept it short,” Bobbi says. “But she did throw her cap in the air when she got her diploma.”

For the Piedmont nurses, the graduation scene illustrates the dignity they protect for the gravely ill and dying. For some, these touching moments preface what nurses call the “transition,” that passage in the course of a patient’s grave illness when it’s time to get everyone ready for what’s coming next.

Protecting dignity is never easy. The wisdom of the ages suggests that suffering and endurance beget hope. With the gravely ill, the embers of hope lose their motivating glow. Endurance and hope have to be shouldered by those who cradle the sick and dying with their care.

“Many of our patients have a goal that keeps them going,” says Bobbi, who works with cancer patients, many in the final stages of life. “Some want to attend a daughter’s wedding, the birth of a grandchild, even a funeral. We try to help them sustain those goals for as long as we can.”

Often the patient is ready for this transition phase, but the family resists. Even physicians feel the powerful tug between what is fully evident and what is wished for. But there comes a time when endurance wanes for everyone. It’s time for the final dignity.

Treating patients in transition isn’t for everyone.

“You have to want to be here,” says Bobbi. “I feel appreciated, that people need me, and that, in the end, they know I’ve helped them through something very difficult. As hard as that can get, you don’t walk away from it.”

The job would be difficult enough if it dealt only with dying patients, but most patients have families who need comforting as well. A picture on the wall at the nurses’ station carries a simple but inspiring caption: “I am someone’s loved one,” a gentle reminder of how much those loved ones need help.

The hospital staff expresses compassion in many simple ways.

“I encourage nurses to sit down when they go into a patient’s room, to not stand there and lean toward the door,” Bobbi says. “Sitting down, facing the patient, will focus your mind on caring instead of just the task you went in the room to perform.”

She describes the simple gifts that nurses offer to patients and families: talking softly while working around a comatose patient, making sure that a patient’s mouth feels clean, turning someone frequently to prevent sores, refusing to leave at the end of a shift if something is still needed.

Bobbi recalls a young patient with a rare, hard-to-recognize ovarian cancer.

“This was difficult because we all adored her,” she says. “She was one of those special elementary school teachers who did so many things for others.

“She had been with us for about six weeks, and we watched her parents and fiancé as they struggled with the idea that she might lose this battle. During this time, the children in her school made ‘helping hands’ for her with encouraging messages. Hundreds of them. We put them everywhere in her room: ceiling, walls, doors, windows. The kids believed this would help her get through this.”

The patient wanted to go home. The nurses knew from her latest X-rays that she had only a few days left. Her physicians and nurses, joined by a chaplain and social worker, met with family members, who didn’t want her told about the prognosis. Nor did they want to call in the rest of the family for a final visit. When the father decided he had to tell her, the nurses helped prepare him for that and joined him in the room for support.

The nurses then made sure she had everything she needed at home. She died within a few hours of getting there. She was 31.

“We still hear from the family and the school, which had a butterfly release in her memory,” Bobbi says. “You put your heart and soul into so many of these people. You can’t help it.”

Relieving the pain of the sick and dying is an ancient medical practice predating recorded history and probably language itself. But “palliative care,” as it is known in the medical profession, has been a board-certified specialty in the United States only since 2008.

The enduring image of end-of-life pain relief is the morphine drip, the last-ditch intervention to “make the patient comfortable.” Fortunately, that image is being replaced by a more modern practice of “symptom relief.” Dr. Kevin Osgood, the head of the Palliative Care department at Piedmont Atlanta, bridges the efforts of those working aggressively to prolong life through therapeutic procedures and those managing the transition. In the case of nurses, the same professionals are cast in both roles.

Dr. Osgood was first trained as an emergency room physician, but soon realized he couldn’t save everyone or even prolong every life. Physicians are action-oriented. The urge to “don’t just stand there, do something” is rooted in their genome. They find it hard to accept the idea that time can run out.

“When we tell patients there is nothing more we can do, we mean we’ve run out of ways to cure the disease,” Dr. Osgood says. “But if our objective is to help patients and families make the journey from diagnosis to prognosis to outcomes, there’s always something we can do for them.”

Time doesn’t “run out” in a patient’s last hour. The signs are evident long before that. That's why palliative care deals with four sets of symptoms: physical, psychological, social and spiritual.

“Only by thinking that way can we treat the patient, not just the disease,” Dr. Osgood says.

The transition can be defined in part by the shift in emphasis from curing a disease to meeting the current needs of a patient.

“That way, when a specific cancer therapy doesn’t work we still know we’ve done everything to help that person through a difficult time despite the persistence of cancer,” says Dr. Osgood continues.

Examples of help through life’s most difficult times are many. There’s the sickle cell patient in and out of the hospital every month who received gifts of coffee and snacks from a special nurse, one who was heartbroken not to be there when he died.

Another patient wanted to live to see one more Christmas, which was weeks away. The nurses knew that was unlikely, so they put up Christmas decorations in his room, bought gifts for other patients as well and helped his family put on a Christmas party for him. His condition was such that it wasn’t certain if he actually knew it wasn’t Christmas yet. It didn’t matter. He was given the care that was called for, not just the care prescribed on the chart.

He died within a week, just before Christmas Eve.

Care and compassion don’t stop when a patient dies. Many families don’t want to leave the hospital while the loved one’s body is still in the room. They don’t have to. The staff makes sure they have time to grieve and say goodbye.

When it is time for the nurses to complete the final tasks of washing and wrapping the body, they do it with great respect, often playing soft music while they work. To them, the patient is still someone’s loved one.

Physicians and nurses have given this person a lot of themselves for weeks or months, doing everything possible to heal and minimize suffering.

“So it’s hard for us to let go,” Bobbi says. “But when we do, it’s important that we do it with respect.”

This is the final dignity.