In the remote mountain towns of northeastern Georgia, state-of-the-heart treatment thrives, thanks to technology. But in the small-town culture of Appalachian communities, technology means little without the human touch of doctors who understand that culture — people like physician/farmer John Kelley.

By Cindy Miller and Edward Miller | Photographs by John Glenn

John Kelley had been busy all morning, so he was looking forward to a quiet lunch break at Mary’s Southern Grill in Young Harris, Georgia. But his entrance in this down-home spot for locals was hardly quiet. It was more like Norm walking into Cheers. Kelley was greeted with a chorus of "Doc, Doc!"

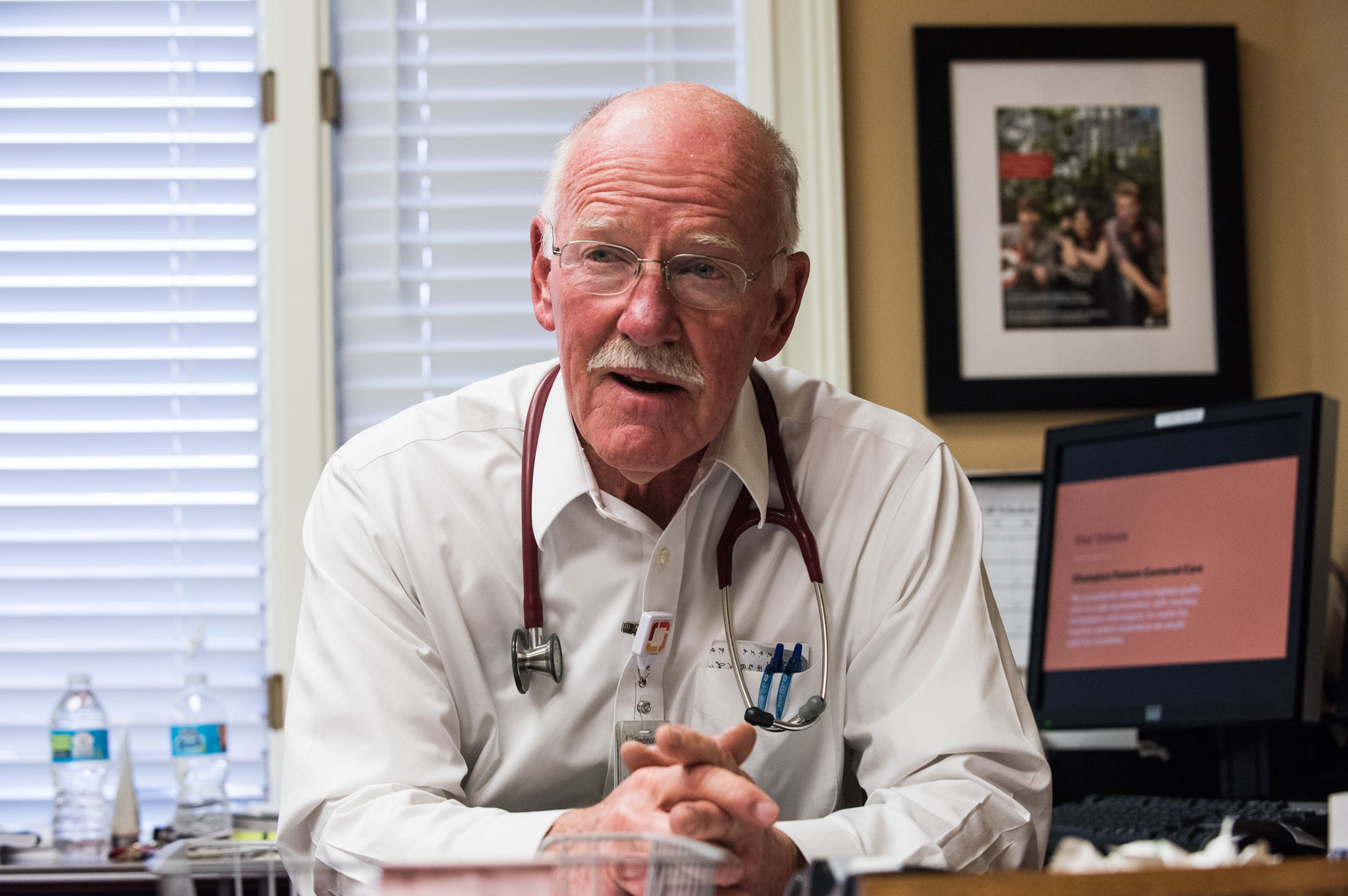

John Kelley is a cardiologist, and a rather famous one at that. But in this part of Georgia, that means more than a stranger with a stethoscope and a white coat, which he seldom wears.

"Done any work today, Doc?" one friend asked.

"Yes, I was at the hospital all morning," Dr. Kelley replied.

"No, I mean real work, farming work."

"Not yet, but it's only lunchtime."

His quiet lunch was a steady stream of greetings from friends and neighbors, including Mary, the diner’s owner, who sat at his booth and talked about a sick friend she had recently referred to him. He treated each interruption as seriously as he would a patient consultation, because many of these folks have been or might become his patients. Besides, politeness is his way.

John Kelley one of several original founding members and a leading cardiologist at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Blairsville, but he fits none of the physician stereotypes. His garb is more likely to be boots, jeans, rodeo belt-buckle, and a rancher's leather hat. He's fifth-generation country. No pretenses.

"I have three goals,” he says. “Glorify God, protect my family, and use my God-given talents to serve others.”

By all accounts, he's doing well on all three.

Rural life in the South is different, but not in the way movies and TV shows portray it. From long experience and deep affection, Dr. Kelley sees mountain culture differently.

“Mountain people often suffer a bad rap — you know, that unfair ‘rube’ image,” he says. “Up here, we take a measure of a man more carefully. If your word is your bond, you’re accepted. Honesty and integrity mean something.”

Rural medicine is different, too. Dr. Kelley calls his work “a country tweaking of Ritz- Carlton medicine,” but tweaking may be too modest a verb. In 2006, when Dr. Kelley moved back to his native Towns County after practicing for 30 years in Augusta, there was no Piedmont Heart Institute.

“I had a successful practice in Augusta, but my roots were here, so my goal was to bring the medical expertise of the city to the country,” Dr. Kelley says. His catalytic efforts started by gathering three existing groups into what was to become the Piedmont Heart Institute network, now a collection of more than 100 specialists spread across about two dozen Georgia locations.

Technology gave the Institute the ability to provide rural patients access to a sophisticated diagnosis close to home. When high-tech treatments like stents, valve replacement or heart transplant are needed, patients are passed along to specialists at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital. “Rural” is merely a location, not a description of a type of healthcare.

A highly coordinated system begins with the careful and personalized methods of diagnosis found throughout the satellite system that contribute to improved outcomes.

“We’ve taken the expertise from the city and delivered it to satellite regions,” Dr. Kelley says. “In that way we can refer people with an accurate diagnosis, not just a problem we can’t solve. If we can treat it here, we do. If not, we can send them downtown to the mother ship.”

Dr. Kelley calls it a down-home approach with sophisticated delivery. To those who work closely with him, this approach means an understanding of the local culture that can have a life-saving impact.

“He has an extraordinary capability to set patients at ease,” says Tanya Chastain, the practice manager for Piedmont Heart Institute’s Blue Ridge and Ellijay locations. She knows this first hand, having also worked as Dr. Kelley’s nurse for two years. “Just knowing that he’s from this area originally makes patients feel comfortable in a way others cannot. Patients relate to him, and take advice from him they just might not take from someone else."

Down-home is something John Kelley knows well. Born and raised on a dairy farm a few miles from his Piedmont office, his childhood was a life of rising at 5 a.m., milking the cows before school, farm chores in the evening, and then doing it all again the next day. The dairy farm was as important as medical school in preparing him to be a physician.

“Medicine requires difficult and arduous training, but it’s easy sledding downhill compared to growing up on a farm with five siblings.” Dr. Kelley says. “It’s a work ethic I learned on the farm and used throughout my schooling and career.”

Dr. Kelley recalls a boyhood incident that helped shape the attitudes that sustained his career:

“When I was very young, the neighboring home of a mother and two daughters burned down. I remember my dad and older brother fighting the fire. They couldn’t save the house, so we took in the family for six or eight months until they could find a new home. What’s worth noting was that there were no agencies involved, no government subsidies to tide them over. They depended on a culture of neighbor helping neighbor. That’s how I grew up. That’s how my world was shaped.”

Family is, and always has been, an important part of Dr. Kelley’s life. His childhood was shaped by a hard-working father who was a farmer and carpenter, and a mother who would care for the family while earning money selling World Book Encyclopedias all over the South.

His family gave him moral and physical strength. It also gave him credibility. “People trusted me from the start. ‘That’s Jack Kelley’s boy,’ they would say. They knew how I was raised.”

His choice of cardiology was also the product of his farm raising. “I was actually studying to be a surgeon,” he says, “but the more I learned about cardiology, the more I realized it entailed characteristics of many of the skills I had learned on the farm: mechanics, hydraulics, plumbing and electricity.”

He also learned to improvise like a farmer.

“In the early days of angioplasty, we used to fashion our own catheters and other devices that weren’t yet available commercially,” he says. “We’d heat them up and reshape them to change the angle in order to get into the arteries. The companies would watch what we were doing and go back to their labs to improve the products and make them available to others.”

Improvisation was part of his musical life as well.

“In ninth grade, I was playing the role of Peter in an Easter pageant. I was supposed to kneel beneath the cross and sing that old Baptist hymn, 'Beneath the Cross of Jesus.' The staging was rather inventive; the cross was backlit, so I was in the shadows.

“Just before I was supposed to sing I heard a voice in the wings whispering to me: ‘Go ahead, start singing.’ It was the pianist, who was also in the shadows and couldn’t read her music, so I had to sing a cappella. That was the start of my amateur solo career, which included singing 'How Great Thou Art' at my grandmother’s funeral.”

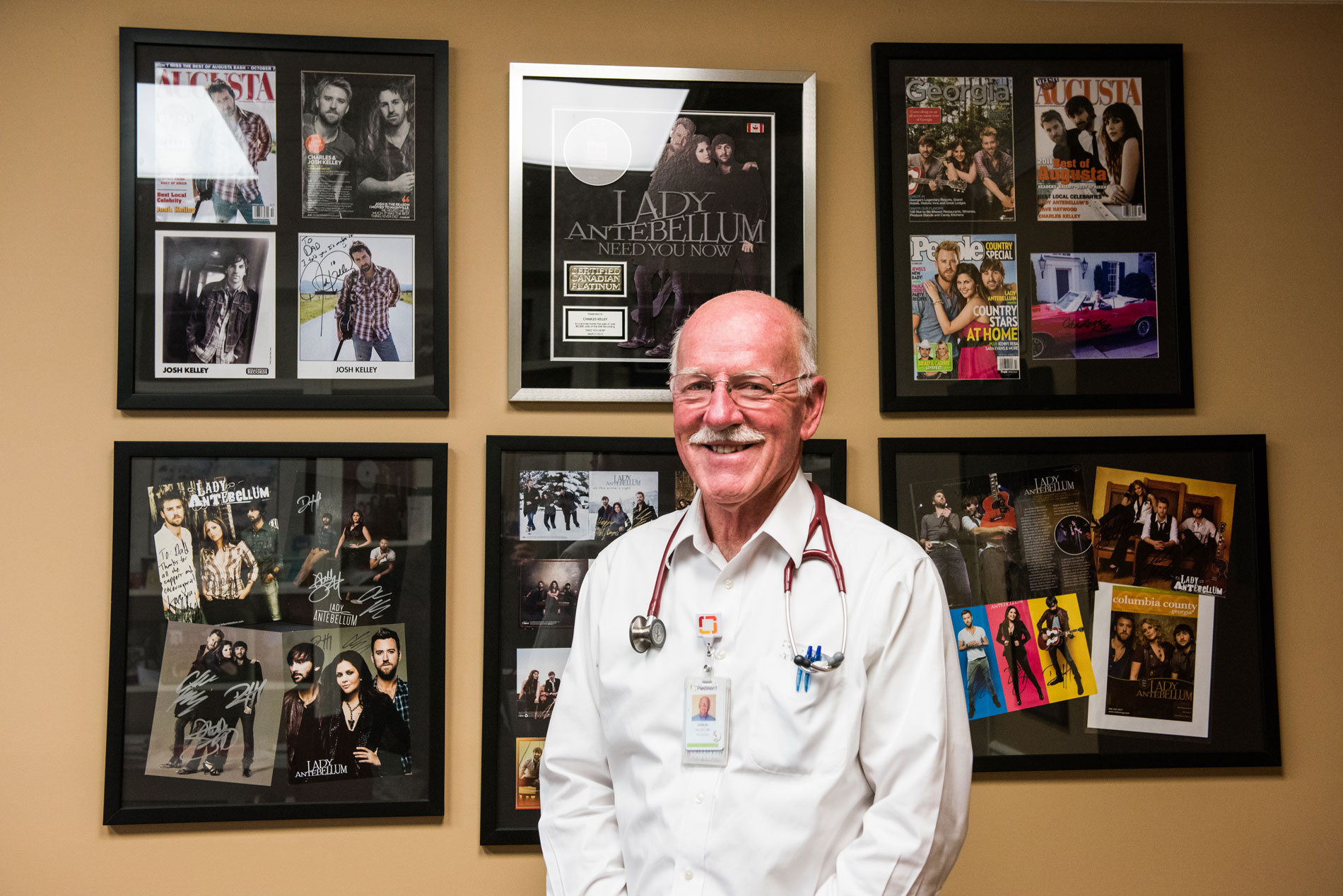

Dr. Kelley passed his love of music — and his strong work ethic — to his seven children, two of whom are professional musicians. Josh Kelley, married to actress and model Katherine Heigl, leads his own band, whose songs are hits on pop and country Top 40 lists. Charles Kelley is a lead singer with the popular country trio Lady Antebellum, which has sent nine singles to No. 1 on the country charts and stacked up seven Grammy Awards.

“I take no credit for their success,” Dr. Kelley adds, “other than exposing them to music and how it can shape the personality of a family. It can turn an ordinary gathering into a memorable event.”

Medicine runs in the family as well. His wife, Angie Kelley, now the director of ambulatory clinics for Piedmont Heart Institute, was a pediatric nurse in Augusta when an overload of cardiovascular patients forced the transfer of a few of them to her pediatric ward. One of her mentors in this quick course on heart patients was a young John Kelley, who today boldly brags about stealing her away to cardiology. Among her early cardiac career highlights was nursing the first heart-transplant patient in Georgia in the mid-1980s.

Back home in Blairsville, Dr. Kelley continues to hear echoes of his past. He describes a recent patient, a woman in her 70s, who needed an aortic valve replacement.

“I took care of her husband for years,” he says. “Both she and her husband were dear friends of my parents, and remember when I was born.”

But then that’s a common story for a country doctor. So, too, are the warm memories of being a farmer/physician. “I used to have a farm with Angus breeding stock,” Dr. Kelley says. “Patients would come in for treatment, but if per chance they needed a herd bull, they would let me know.”

The walls of his Blairsville office are covered with mementos of patients –– a walking stick, a painting, a child’s woolen cap –– many of which were payments from those without insurance during his private practice days.

It’s an office out of a Norman Rockwell painting, yet Kelley merges his folksy small-town demeanor with the sophisticated practices of the nation’s top cardiologists. One by-product of this blend is the ability to attract talent. Dr. Katherine Duello is a good example. An Augusta native, Dr. Duello did her cardiology residency at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville. That might have been a stepping stone to a prominent big-city hospital anywhere in the country, but last fall she chose to come back to Georgia to practice. Why?

“The quality of medicine is as good here as it is at the Mayo Clinic,” she says. “But at a big-city hospital, you tend to treat out-of-towners who eventually return home. There’s little opportunity for follow-up. Here, I can treat locals and establish long-term relationships with them as people and as patients. That’s a lifestyle benefit that I value.”

When Dr. Kelley speaks of his heritage, he uses terms like sanctity, dignity and respect for the moral values he sees in mountain culture. Unlike many urban physicians, he knows his patients intimately as friends and neighbors. They see each other in stores and at civic meetings. Community is more than geography; it’s a way of life.

He describes his medical mission with the metaphors of the countryside:

“As I grew up, I learned to take a piece of land that might not have much worth and work with it until it was a productive site,” he says. “That explains my professional goal to bring to this community a level of cardiac care that was better than what I found here. Driving me toward that goal is a conviction that there should not be a difference in medical care based on where you live or your economic background.”

That’s the paradox. Because of the bonds and connections in rural life, its medicine can be as good or better than that found anywhere.

Dr. Kelley is an elder statesman in medicine now, and has seen a lot of changes — some of which he helped develop himself. "I was doing angioplasty in its infancy," he says. "I would put a patient in my car and drive him to Atlanta for the procedure." At the time, the procedure was typically done only in New York City and San Francisco.

He is modest about his pioneering contributions: “Let’s just say I helped make the technology available to community hospitals.” Humility is in his DNA.

Medicine in rural areas in the past was often hampered by distance from the most sophisticated and up-to-date services. Piedmont Heart Institute has overcome that obstacle through technology and organizational inventiveness. Dr. Kelley tells the story of the husband of one of his high school teachers. The man had a concerning heart murmur, and tests revealed a severe problem with his aortic valve — one that required catheterization.

It didn’t matter that there was 100 miles separating the diagnosis and treatment in Atlanta. Piedmont’s technological and communications networks provide access to all points along an interconnected spectrum — from early diagnosis to treatment and rehabilitation. Rural still means personal and neighborly, but it no longer has to mean remote and disconnected.

“He is now a new man, but I wouldn’t have been able to tell that story 10 years ago, because then he might not have felt confident enough to come in for an exam in the first place,” says Dr. Kelley “That’s how far we’ve come in providing advanced healthcare in this community.”