In St. Augustine lie the ruins of Fort Mose, built in 1738 as the first free black settlement in what would become the United States. The story of its people and their leaders will make you wonder if America might have developed more enlightened racial attitudes if the Spanish had conquered the British for possession of the New World. And the story of the man who found Mose’s ruins reminds us, yet again, of the complex and confounding nature of the South.

Florida is not typically the first place that comes to mind when you think of the Enlightenment.

No, the state is more closely associated with tourism, swamps, shady land deals, environmental devastation, and cantankerous old men. For this, it has been the object of America’s ridicule, resentment, and, increasingly, pity and affection.

We’ll certainly get to all that because most stories about Florida devolve into the same hoary tropes. Everything here is sad, and everything here is funny. I know you people want to hear the hits, but they are merely impressions left by Florida’s scads of interlopers, like footsteps in the sugar sand. Besides the swamps, nothing of this place is native.

But before the cliches took hold, before the peninsula became the corridor of convalescence for wealthy northerners, when Orlando was still a swamp, and Lake Okeechobee was known as Laguna de Espiritu Santo, something remarkable took place early in Florida’s colonial period. This incredible occurrence existed as a distinct foil to the horrors of colonialism, and it was skillfully glossed over in American history because it didn’t really belong to America.

The story suggests that America more accurately belongs to Florida. The state with the longest recorded history of any state in the country. The account that was never well known to begin with, and for that reason always seems one bulldozer or king tide away from oblivion.

The first known European encounter with Florida was by Spain’s Juan Ponce de Leon in 1513. After being deposed as governor of Puerto Rico, Ponce charted north in search of better prospects and a clean source of water. He landed near the Timucua village of Seloy (present-day St. Augustine, although exact locations are hotly contested) and claimed the entire Atlantic coast La Florida: “The Flowery Land” for Spain (or so he thought, as if it had been Spain’s for the claiming). Ponce filled his cisterns with the natural spring water bubbling up from the Florida Aquifer and left five days later. His fleet sailed around the Florida Keys and landed near Charlotte Harbor on the Gulf Coast. During a battle with the Calusa Indians, Ponce was shot with a poisoned arrow. He returned to Cuba, where he promptly died.

On September 6, 1565, 52 years after Ponce, another conquistador arrived at roughly the same location: Pedro Menendez de Aviles. He had agreed to the voyage so he could search for his son Juan, whose ship had gone missing after being caught in a hurricane off of the Florida coast. Menendez planted the Spanish Cross of Burgundy at the St. Augustine Harbor. In doing so, he founded a city — the first permanently occupied city in America — but never found his son, despite searching until the day he died.

Spain’s Juan Ponce de Leon

Pedro Menendez de Aviles

Long before Jamestown, there was St. Augustine. There had already been a generation of children born in Florida by the time the English established what history books tell us was the first permanent colonial settlement in America. St. Augustine is not only the first capital of Florida but the first capital of the country and putative site of the first convivial meeting (or “Thanksgiving,” if you like) between the Spaniards and the Timucua — between Pedro Menendez and the Seloy “cacique,” or chief, Saturiwa.

It’s hard to say anything good about the Spanish presence on this continent, knowing what Spanish warfare and disease did to native populations. Nevertheless, in relation to the American Experiment, Spanish St. Augustine has mostly gone uncredited as the original “city upon a hill” — the fleeting first example of a proto-liberal, proto-enlightened, diverse society of European origin in the New World.

If Spain hadn’t lost its footing, the Florida peninsula — perhaps the entire country — would look much different than it does today. Ground zero for Spanish Florida’s brief experiment in progressive society was a place called Fort Mose, which was also the setting of a more modern kind of Florida story when, 230 years later, a prickly World War II Veteran began uncovering the fort’s ruins.

Fort mose rendering courtesy of the university of florida

Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, or Fort Mose (pronounced MOH-say), was established in 1738. It is now considered the first free black settlement in what would become the United States of America. Alternatively spelled Mosa, Moosa, Mossa, and Moze — translated to moss in all respects — Mose was the last stop on the original Underground Railroad, which began in the South and pointed not north but further south, toward a pine forest on a swamp facing the Atlantic Ocean. To the edge of St. Augustine.

No discussion about Fort Mose opens without Francisco Menendez (no relation to Pedro Menendez de Aviles). Menendez was a Mandinga boy captured in his West African home and enslaved in the British colony of South Carolina. He had twice escaped from slavery, disappearing into the coastal swamps of Carolina and Georgia, where he lived for years among the Yamasee Indians and led his first successful military campaign against his former masters in the Yamasee War. Menendez was fated to become the revered captain of the free black militia in St. Augustine, and a founding member of Fort Mose.

In 1725, a group of runaway slaves turned up in St. Augustine seeking refuge in the rumored Spanish sanctuary state. They had fled Charleston, South Carolina, after word spread of a royal decree from the Spanish king that promised liberty to all fugitives who came to Florida seeking Catholic conversion. They were led by Francisco Menendez (given that name in baptism once he arrived in Spanish territory, his birth name is unknown). Unlike their neighbors to the north, Spain had largely attenuated their slavery practices by the turn of the 18th century. Historian Jane Landers notes in her seminal book Black Society in Spanish Florida that runaway slaves from British plantations had been fleeing to Florida since the late 17th century. The first documented runaways from Carolina made it to St. Augustine in 1687. And then again in 1688, 1689, and 1690.

Mixed societies, which included a free black class, had long existed in Spain, a precedent commonly attributed to the Moors’ occupation of the Iberian Peninsula. Landers also points out by the time Mose was founded, free black towns in the Spanish colonies of Panama, Venezuela, New Spain, and Hispaniola had already been established and received a royal sanction.

Yet it was not uncommon for runaways, or “maroons,” to be re-enslaved once they reached Spanish territory. In messages directed at the Spanish crown, Francisco Menendez wrote it was unacceptable that only some fugitive slaves had been freed when others hadn’t, even if the conditions of Spanish slaveholders were favorable to the chattel slavery of the British. In their conversion to Christianity, runaways had upheld their end of the bargain.

Not until March of 1738 did Manuel de Montiano, the 41st colonial governor of Florida, officially free all runaway slaves and establish Fort Mose to house the burgeoning numbers of fugitives arriving in St. Augustine, a result of Menendez’s persistent petitioning. Governor Montiano installed Menendez as the captain of the free black militia and the de facto leader of the fort. An obvious choice, Menendez spoke four languages and held a decorated military dossier. He chose his lieutenants. Residents of the fort were referred to as his “subjects.”

None of this is to say the settlement was some great expression of Iberian altruism. Delivering a man from slavery under strict military and religious pretenses is just another variation on enslavement. And, in a sense, recognizing and writing policies as a response to the condition of slavery is to validate something that should otherwise be considered arbitrary. Fort Mose can best be understood as a creative solution to a litany of colonial problems that marred Spanish Florida. In no small part, the settlement owed its existence to the ongoing competition between Spain and England for control of the Southeast. A stated goal in inciting runaways was to disrupt the British slave economy, but also to use the black militia as a parapet against potential invasions. As such, tentative freedom for the enslaved class of the Carolinas — which by 1700 vastly outnumbered the white planters—was within reach, just across the St. Marys River and into North Florida.

British slaveholders were fully aware of the so-called sanctuary settlement in St. Augustine and the Indian guides who led runaways there. South Carolina slave revolts in 1711 and 1714 were blamed on the Spanish, as was the infamous Stono Rebellion in Charleston in 1739, one year after Mose was founded. Carolina planters responded to slave uprisings with increased repression. Harsher bills were passed to prevent rebellions. British planters paid Indian, white, and black slave catchers to track and kill escaped slaves “whose owners were then compensated from public funds,” as Landers notes. Captain Caleb Davis, a slaveholder from Port Royal, South Carolina, turned up in St. Augustine to recover two dozen of his slaves, who had successfully escaped to Spanish Florida. Governor Montiano refused. Davis’s former slaves reportedly laughed him out of town.

These provocations would inevitably culminate in armed conflict. Governor James Oglethorpe of the newly formed Georgia territory invaded Florida in 1740, heading straight for Mose. Residents of the fort retreated to St. Augustine and were locked within the throwing-star-shaped Castillo de San Marcos, the oldest masonry fort in the U.S. The Castillo thwarted two bombardments during Spanish occupation and “still stands today, its dank gray walls brooding over the city it saved,” as Florida’s preeminent historian Michael Gannon wrote. Its porous, coquina-shell bulwark swallowed British cannonballs like marbles in Jell-O.

The throwing-star-shaped Castillo de San Marcos, the oldest masonry fort in the U.S. photo by Jordan Blumetti

After a month of being garrisoned at the Castillo, Captain Antonio Salgado and Captain Francisco Menendez led their militias to Mose at dawn and slaughtered just about every last British soldier who had been occupying the fort. The battle would be referred to as Bloody Mose by the few surviving British troops. They witnessed bludgeoning, castration, and beheadings at the hands of their former slaves who were led by the canniest militiaman, Francisco Menendez. His name was now infamous among British soldiers.

A disgraced Oglethorpe escaped with his life and retreated to Georgia. The black militia burned everything that wasn’t destroyed in the battle. With nowhere else to go, the displaced residents of Fort Mose went on to live within the city walls of St. Augustine, where there had already been a mixed European and Native American citizenry. But now, a class of free blacks was added, and for the next 12 years, a social condition emerged that, for its time, was unlike any other in North America.

Francisco Menendez had higher ambitions. He became a corsair and sailed off with the Spanish Armada, intending to reach Spain and appeal in person to the crown for an officer’s salary, which he felt was owed to him for his service to Spanish colonial ambitions. In his unrequited letter to the King, he wrote, “My sole object was to defend the Holy Gospel and the sovereignty of the Royal Crown … although it advanced my poverty.”

He was soon captured by a British ship off the coast of North Carolina. Unable to conceal the fact that this was the same man who led the assault at Bloody Mose, Menendez was tortured, “brined and pickled,” and shipped to the colony of the Bahamas, condemned to slavery once again.

Menendez would unfortunately not be around to witness what transpired in St. Augustine over the next two decades. After 150 years of Spanish rule, St. Augustine matured into a comparatively progressive society in an epoch where nothing good seemed to exist. It was a polyglot community, with an excess of languages and cultures: any number of Spanish, Irish, Italian, German, Portuguese, Guinean, Congolese, and Timucua.

Map of st. augustine and fort mosa, courtesy of the university of florida

St. Augustine stood in stark contrast to the white European cultural hegemony that pervades colonial narratives. The Panglossian blueprint for America, as we often perceive it today, was devised in Spanish Florida, an earnest Spanish experiment before an American one. It’s not an overstatement to say that in 1741 the first city looked more diverse than it does today. Indeed, this notion of diversity still seems aptly provisional and elusive.

The free blacks of St. Augustine fished and hunted, were building contractors, rounded up wild horses and cattle, tracked escaped prisoners. They owned land and generally fared for themselves. When the mullet weren’t biting, they were given corn and beef from government stores. But as the number of runaway slaves increased and the threat of British encroachments loomed, a new administration in Spanish Florida ordered Fort Mose rebuilt at a larger site adjacent to the original one. In 1752 — after living within the city limits for nearly 12 years — the black community in St. Augustine was moved, more or less forcibly, back to their billet on the outskirts of town.

Meanwhile, in the Bahamas, the artful Menendez had prevailed once more. As Landers writes, “Francisco Menendez might well have been among the ‘disappeared’ of the era; however, as he proved many times, Menendez was a man of unusual abilities. Whether [he] successfully appealed for his freedom in British courts as he had in the Spanish, was ransomed back by the Spanish officials of Florida, or escaped is unknown, but by at least 1759 he was once again in command at Mose.”

Menendez returned to St. Augustine as it had looked before Bloody Mose, not with its black citizens living in the city center, but on the periphery. To make matters worse, it was also spiraling into bankruptcy.

By the early 1760s, Spain’s sustained effort to populate and build the inhospitable Florida frontier into a viable colony was a resounding failure. Spain would ultimately go broke on the prospect of Florida. It was nearly impossible for residents of Mose to meet their own needs, and the Spanish government could no longer afford to subsidize the fort.

The geopolitics of the day forced Spain into ceding Florida to Britain as a ransom for Cuba (although Spain would temporarily regain control of Florida after Britain’s defeat in the Revolutionary War).

Once there was no more Spanish St. Augustine, there was no reason for a Fort Mose to protect it. The fort served an invaluable objective for the city in its time, a “negroid littoral” as the scholar Leon Campbell put it. Had the residents of Mose not been placed directly in the line of fire, they might have avoided military conscription. Then again, armed combat against one’s former captor might have satisfied a palpable, bloodthirsty vendetta. A pure, exploitable emotion.

In August of 1763, at age 49, Captain Francisco Menendez, his wife Maria de Escovar, and the 50-odd remaining residents of Fort Mose sailed to Cuba on a schooner named Our Lady of the Sorrows. They landed in Ceiba Mocha and, alongside their Spanish compatriots, christened their new settlement San Agustin de la Nueva Florida (Saint Augustine of the New Florida). No descendants of the original fort were identified, living or deceased. Likewise, nothing of Menendez’s remaining years has survived.

Thus ended, at least for two more centuries, the story of Fort Mose.

In 1995, Florida Representative Alzo J. Reddick of Orlando said St. Augustine should become a tourist mecca for African-Americans. He cited Fort Mose in particular, which had recently come to light after a series of archeological digs funded by the state of Florida and backed by the Black Legislative Caucus.

Twenty-three years later, there has been no such development. Fort Mose is a place even most St. Augustinians do not know about, which is symptomatic of a more significant issue: the trouble this city has had in the pursuit of autobiography.

Roughly 7 million tourists visit the city annually, but they are not necessarily coming for a history lesson. And if they do, it’s often the Disneyfied version — a history unmoored from history, complete with snack bars and swashbucklers and torture chambers, with alligator farms and ghosts tours, and yet more snack bars.

A struggle between historical accuracy and a tawdry gimmick economy has existed in St. Augustine since Reconstruction. An essay from 1937 by historian Charles B. Reynolds titled “Fact Versus Fiction for the New Historical St. Augustine” remarks on the inauspicious establishment of the St. Augustine Historical Society and a series of historical fallacies created to beguile tourists. If the cutting sentiment behind “New Historical St. Augustine” from the title wasn’t enough of a reproach, the author’s foreword states:

“The history of the town’s beginnings current in St. Augustine is of a dual nature. On the one hand, it is as chronicled by contemporary writers some of whom had personal part in the events recorded. On the other hand, it has been invented within the past 30 years by persons ignorant of or contemptuous of the original contemporaneous records. The two elements are discrepant, contradictory and irreconcilable. To believe one is to disbelieve the other.”

That inferior hand is comprised of “flimflams, pure and simple, concocted for the mercenary hoaxing of tourists.” Landowners in St. Augustine were grilling up their own versions of history and selling tickets on their front lawns.

One of the oldest scams in town is Ponce de Leon’s Fountain of Youth, purchased in 1904 by Luella Day McConnell — known among St. Augustine residents as Diamond Lil, on account of the diamond curiously set in her front tooth — with the fortune she made in the Klondike Gold Rush. This was the site where, some argue, Ponce de Leon and Pedro Menendez de Aviles landed in 1513 and 1565, respectively. Diamond Lil was the first to call the well on the property the “Fountain of Youth,” a satirical phrase which first appeared as an irreverent joke at Ponce’s expense and by the 17th century had become accepted history. Diamond Lil began charging for admission, selling cups of water for an additional 10 cents.

Diamond Lil's Fountain of Youth, now and then. Archival photos courtesy of the Florida State Archives

Park administration has since cleaned up its act, no longer claiming the spring water has mystical anti-aging powers. Today, a ticket will run you $15. A statue of Ponce stands valiantly at the entrance. For some unknown reason, there’s also a muster of peacocks that swagger across the parking lot, squawking at tourists as they fumble out of their cars. They are curtly shooed away, dragging their iridescent, many-eyed plumage back and forth across the asphalt like the trains of unwanted brides.

The early St. Augustine Historical Society, as well as politicians, were at the center of the controversy. Finding itself with more influence and responsibility than was initially ventured, the Society was often in on the ruse, and unable to stop people like Diamond Lil from peddling whatever yarn sold the most tickets. This dual nature of dubious landmarks mixed with legitimate ones formed the conflicted basis of regional history. Being in downtown St. Augustine today, one is still up against a barrage of extraneous, anecdotal dispatches. Commercial tourism competes with whatever real history beckons. The guided tours run all hours. They intersect and interrupt one another. A walking tour going one way, a rickety trolley going another. A horse-drawn carriage, a rickshaw. The tour guides always in mid-sentence, echoing down craggy cobblestone lanes. A desire exists, as W.G. Sebald once said, to reach out and rescue something from that stream of history rushing by.

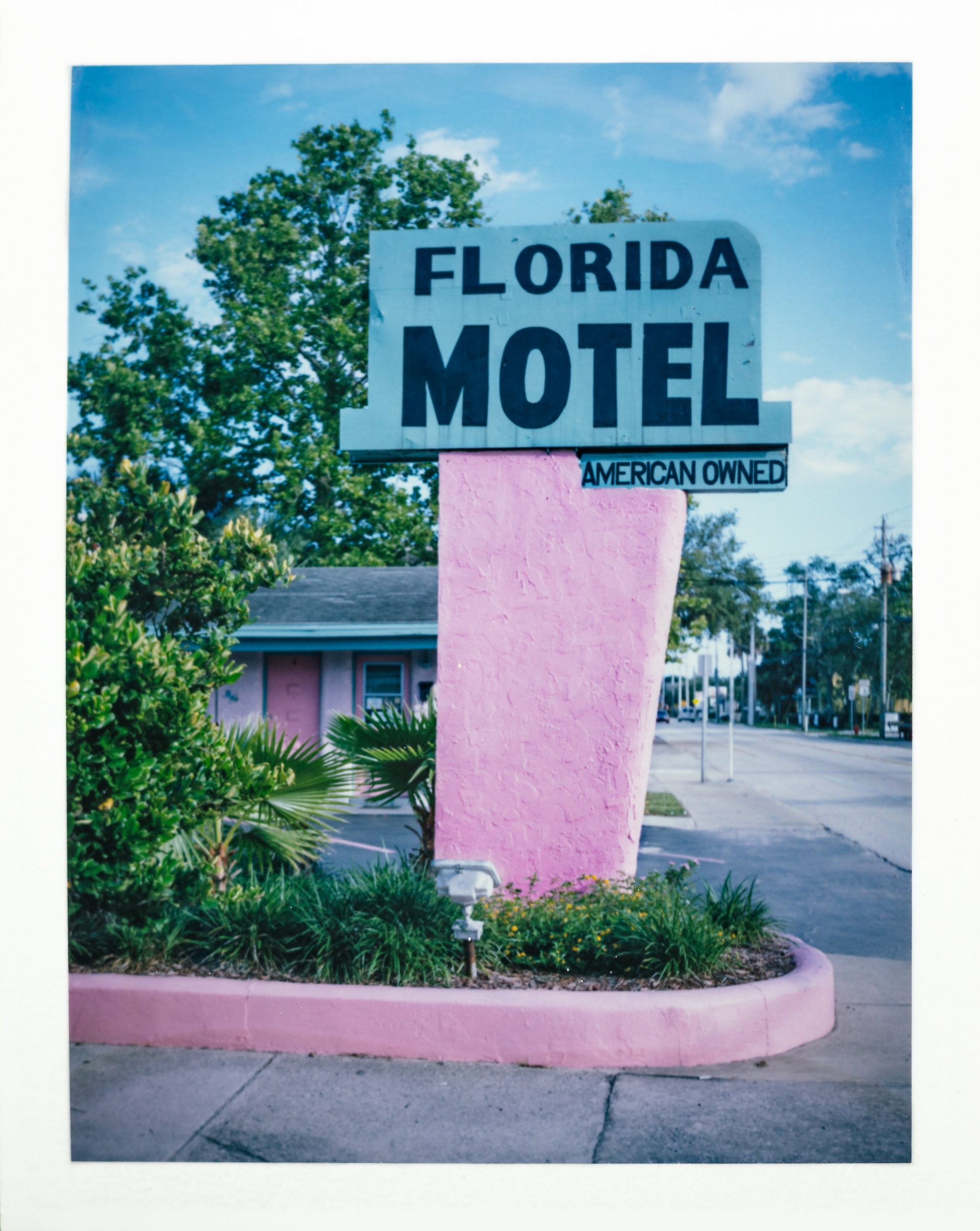

Driving north on U.S. Route 1, past the Fountain of Youth and the Old City Jail and Ripley’s Believe It or Not, where the tourist shuttles no longer run, where the Raddisons and Travel Lodges give way to non-franchised, increasingly vacant motels — here, just outside the city limits of St. Augustine, there is a brown road sign about the size of shoebox. It reads “Fort Mose” in spartan white letters with an arrow pointing east.

I slammed on my brakes to make the turn, inciting some vitriol I spotted in the rearview. It snuck up on me a couple hundred yards north of the welcome sign for St. Augustine, which seemed to imply that all things outside the sign, permanently fixed or not moving toward it, are somehow unwelcome.

There had been some nasty weather. The sky was one massive cloud bank. The storms left small craters of standing water all around the park entrance, scourges of mosquitos conspiring above.

The Visitor’s Center at Fort Mose State Park

The Visitor’s Center at Fort Mose State Park is the only structure on site. A squat, ash-grey building, with a line of African tiles near the foundation that dress up an otherwise drab, government facade. The name was misleading in the sense that the building is conspicuously light on visitors. There was a lone group of birders standing in the empty parking lot with craned necks, binoculars pointed at the flashy, gray and white sky. They were motionless — visitors, but not very good ones, what with their fey indifference to terrestrial matters.

“What’s up there?” I said as I approached the doors.

“We think it’s the yellow-throated warbler,” one replied, faintly, face still buried in her binoculars. “If you see him, let him know we’re looking for him.”

I found Carl Marchand, the park supervisor, in a small room adjoining the entrance. He and a volunteer were working on renovations to the center’s media room. They had a set of doors propped up on sawhorses, rolling on a coat of paint. Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” was playing over a tinny stereo in the corner. He put his brush down and led me into his office. A large man, with a thick, salt-and-pepper mustache and a blocky head, his algae-colored park-ranger pants sagged below his stomach line.

The first site of Fort Mose is now underwater, he said. All that remains of the second site — the larger more robust version built In 1752, 12 years after Bloody Mose — is the half-eroded structural bank overlooking Robinson Creek (formerly Mose Creek) with salt marshes fanning out on all sides.

“At the time, this was all upland agricultural land. Mose Creek was what ran behind both sites,” Carl said. “Henry Flagler came through in the late 1880s and dredged the area for fill for construction of the buildings that make up downtown St. Augustine. Like [Flagler] College, which used to be the Flagler Hotel. So it’s reverted to becoming the salt marsh you see out there today.”

The site of fort mosa has reverted to salt marsh partly due to the dredging of Henry flagler in the 1880s.

He told me about the founding of St. Augustine, Spain’s unique social theories, the remarkable story of Francisco Menendez. He said the artifacts in the Visitor’s Center came from the relatively recent material discovery of Fort Mose. The discovery, as Carl put it, “lends itself to our being the first legally sanctioned, free black settlement in what is today the United States.”

The lead excavator on those digs, which began in the 1980s, was the critically acclaimed archeologist (and a person who would not respond to my emails) Kathleen Deagan. She worked in conjunction with Jane Landers, then a doctoral candidate at the University of Florida, now a professor of history at Vanderbilt (who answered my emails, albeit laconically). Together, they located the approximate sites of the first and second forts. Deagan and Landers are credited with the material discovery of Mose. Their names are everywhere — on placards, in pamphlets, in welcome videos. But little is said publicly of exactly how these two scholars arrived here in the first place. In other words, what led them to investigate this overgrown and anonymous purlieu of St. Augustine?

click to enlarge the image of the park brochure

Jane Landers said, not inaccurately, that everything I needed to know could be found in her book. Kathleen Deagan, on the other hand, showed commendable restraint. She literally said nothing, to the point of my triple-checking I had the right email address. It was true that everything I needed to know was in Landers’s book, but not everything I wanted to know.

Murmurs of a free black antebellum settlement near St. Augustine had been circulating since the early 20th century. There were mentions in Spanish and British colonial records and renderings on 18th-century maps. Irene Aloha Wright, one of the great underrated historians of the last century, produced volumes of English translations from the Archives of the Indies, in Spain, from which details about Mose were extracted. Wright penned an ethnographic sketch and timeline of Mose in The Journal of Negro History in 1924. And no less than Zora Neale Hurston, forever with her finger on the pulse, later contributed another report on Mose to the Journal in October 1927. (Not only was this the same year that Hurston would first visit Cudjo Lewis, subject of the recently published Barracoon, but her trip to Mose was also part of the very same research commission from the Journal’s editor that led her south, first to Florida and then Plateau “Africatown,” Alabama. Hurston’s first story about Cudjo Lewis, “Cudjo’s Own Story of the Last African Slaver,” appeared in the same issue as her report on Fort Mose.)

But it wasn't either of these two women (or the handful of rare texts that made passing mention of Mose) that put Deagan and Landers on the trail. It was Air Force veteran Frederick Eugene Williams III, the man they called Jack.

Jack Williams ran an antique-weapons museum in downtown St. Augustine in the 1960s and ’70s. A somewhat fanatical historian of a prominent military bent, he was also a lifelong member of the St. Augustine Historical Society.

He became interested in Fort Mosa (MOH-suh, as he pronounced it, the Anglo version) sometime in the 1950s, after reading a piece of historical fiction set in Florida called The Flames of Time. His interest soon grew into a formidable obsession. The exact location of Mose was still unknown, but Jack researched the site extensively until he became convinced the lost fort was somewhere beneath a salt marsh two miles north of town.

The parcel of land he identified happened to be owned by the Historical Society at the time. Local Judge David R. Dunham donated the property to the society in the early part of the 20th century. Jack would show up at Historical Society meetings with his 200-year-old maps and an armful of colonial documents, ranting with increased fervor about commissioning archeological digs, only to be met with a stifled yawn.

The Historical Society wasn't interested in Jack’s discovery, which they considered misguided, but they still let him conduct his own field research until imperiously revoking that privilege due to financial strife. The 1960s were troubled times for the Society. After losing its contract to operate one of the more lucrative tourist attractions — the Castillo de San Marcos — it began hemorrhaging money. The land that Jack said contained Fort Mose would thus be put on the market for developers to cover mounting debts. As the Historical Society moved closer to a sale, Jack swooped in at the 11th hour and purchased it himself for $10,000. The year was 1968.

JACK WILLIAMS WITH PISTOL 2003, Photo by WALTER COKER

The Williams family moved from their stately home in the center of downtown St. Augustine to a concrete block house on the salt marsh just outside the city. It was Jack, his wife, and their son and daughter — Dana and Diana.

Jack’s fixation on Mose consolidated. He financed land and aerial surveys of the property to pinpoint sections of interest. Pictured in aviator sunglasses, swamp boots, corduroy shorts, and terry-cloth bucket hat — often shirtless, occasionally with a revolver on his hip, looking every bit of Hunter S. Thompson from the Sugarloaf days — he waded through tidal creeks, parted sawgrass and saw palmettos, digging.

JACK DIGGING NEAR THE BIG ISLAND AT MOSA, photo courtesy of the williams family

“Days and days and days; weeks, months of digging in the mush and the muck and the rain and the heat,” he said. Jack pulled materials from daily life at Fort Mose out of the marsh: glass shards, broken weapons, gun flints.

His money dwindled. His wife left with their daughter in late 1969. His son stayed behind. A few years later, at the precise moment when Jack felt he was on to something incontrovertible, he put down his spade and called the University of Florida. The archeology department, where Kathleen Deagan was then a student, arrived in 1972 to conduct some preliminary tests. It would take nearly 15 years, but the archeologists returned with their excavation tools and gadgets, plus a $100,000 grant from the State of Florida. That’s where Jack’s trouble began.

“It was Dad. Without him, none of this would have been possible,” Jack’s daughter Diana Hamann (née Williams) says. “It’s terrible what happened to him.”

Diana was eight years old when her father purchased Fort Mose. She remembers feral weekends on the island, picnicking and chasing quail with her brother while her father dug for artifacts.

By the late 1980s, Deagan had endorsed Jack’s discovery of Mose. He was right, she said. It was at this point, Diana remembers, the State of Florida became interested in acquiring the property for historical purposes. Her father received a letter from Tallahassee congratulating him for the discovery. Not soon after, the state issued its first offer: $23,800.

“I told them to get lost,” Jack remarked to a reporter in 1989. He wanted about ten times that. The value of a piece of coastal land that size had substantially inflated over the previous 20 years.

The second offer came in: $29,700.

“Go jump,” Jack said.

The state came back a third time, with $100,587.

“I told them to go to you-know-where.”

Where they ended up was in the courtroom. In an acrimonious legal dispute that cost Jack a small fortune and divided the community on their perceptions of the man, the state won the property for $100,000 through an ad hoc version of eminent domain, written with the express goal of acquiring Fort Mose.

Williams family picnic, 1968, photo courtesy of the williams family

“He was branded a money-grubbing jerk, and it killed his reputation,” Diana says. Even before the sloppy custody battle over Fort Mose, there were certain members of the community who took a dim view of Jack. Although he was regarded by select friends and contemporaries as an “expert” colonial and military historian, Jack was uncredentialed, and therefore considered to be of amateur distinction, a rank for which he harbored a lifelong enmity. It worked against him in the courtroom, and in the court of public opinion. He became the greedy, impudent landowner refusing to concede a historical site to the state, and he was no longer recognized or celebrated for being the sole reason no housing development or marina stands there today.

Greed was not the worst charge. The more damning accusation was the one that branded Jack a stark racist. An article in the North Florida alt-weekly Folio — titled “White Man’s Burden: How an unapologetic good ol’ boy became the savior of black history in St. Augustine” — effectively skewered Jack and his motivations. The indictments of his character were abundant and variegated.

Jack’s son, Dana, argues the Folio story was ad hominem. He points out that Hamilton Nolan, the story’s author, is the son of David Nolan, one of the most prominent and revered historians in St. Augustine who had an adversarial relationship with his father.

“There can be little doubt that the St. Augustine Historical Society’s lack of knowledge about the site in the ’60s and its subsequent sale to my father was very embarrassing,” Dana says. “Some people were trying to capitalize on the positive attention Mose was receiving to pad their professional resumes, and they may have been envious of the attention Dad was getting.”

“Jack would never speak to me again after that article appeared,” David Nolan says in response. “I always considered him a friend, a somewhat eccentric friend, but a friend nonetheless. [The story] was not out of hostility, and I certainly didn’t try to pass off any hostility to Hamilton.”

The piece merely captured Jack’s character, he says: “I thought it turned Jack into a folk hero.”

For his part, Jack seemed unperturbed by the charges of impropriety (save for the fact that he was quoted taking the Lord’s name in vain). And even if he wanted to, he could do little in the way of untangling the Gordian knot. Certain loyalties of his own manufacture hurt his case. Throughout his many years of mining Fort Mose, Jack maintained that his primary interest was in the site’s recondite military history, not what appeared to be the ascendant narrative — that of runaway slaves finding sanctuary in Spanish Florida, and what that story meant for the colonial history of Africans on this continent.

Jack Williams at Fort Mosa, 2003 Photo by Walter Coker

“It was [Mose’s] weird, quirky military history that he was into — not the African-American history,” Diana says.

She refers to the relatively unknown Patriot War of 1812, which took place near Fort Mose 50 years after Francisco Menendez had sailed off to an uncertain future in Cuba, taking the story of the first free black settlement with him. As Jack saw it, Diana says, the Patriot War was the first secret war carried out by the U.S. government.

During the Second Spanish period, American patriots, backed by James Madison, invaded North Florida with designs to overthrow the Spanish government and turn the peninsula into a U.S. territory. The war was a complete failure. But the story, which Jack first read about in The Flames of Time, a work of misty-eyed historical fiction, consumed him to the point that he bought the property and searched for the remnants himself. A military man at heart and deeply invested in history — which is to say never truly of the present moment — Jack was given to military euphemisms. In this first government-backed secret war, Jack divined clever parallels with the secret wars of his day. He was, after all, a veteran living in Cold War America, the period when America’s covert involvement in regime change was at its most prolific, spanning four continents.

Jack repeatedly said he was just not aware of the black narrative upon beginning his investigation all those years ago. Dana and Diana recall that he wholeheartedly adopted its cause once Deagan’s excavations began to reveal not the obscure Patriot War of 1812, but the discovery of America’s first state-sanctioned slave sanctuary.

But the claims of his exhaustive research, as stated by Jack and his family, make this notion difficult to abide. He could not have committed himself so entirely to the scholarship and history of this particular site without encountering some material regarding the slave sanctuary, especially those early reports from Irene Wright and Zora Hurston, which were published in an American academic journal right under his nose. Hurston opens her story by outlining every which way the name of the fort may be uttered, including the variation Jack preferred:

“Near St. Augustine,” Hurston writes, “there is evidence of an old Negro Fort called Fort Moosa (also spelled Moze, Mosa, Mossa, Mose, translated means Moss). There is a map of the Fort Mose, three miles from St. Augustine, on General Oglethorpe’s map of 1740, a copy of which may be had from the Library of Congress, Division of Maps.”

“He was a man of his generation, with all the complexity that entails,” Diana says. “I challenged my parents about their racial views my entire life.”

Unlike two centuries prior, race relations in the oldest city in Jack’s day were as bad as anywhere in the country. On the laundry list of essential, yet little known historical details about St. Augustine is its pivotal role in the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The intensely segregated “ancient city” had been preparing for its 400th-anniversary celebration when things went awry. Members of the Florida state legislature and local politicians were taking the opportunity to package St. Augustine as “the oldest community of the white race in America.” In addition to promoting integration, civil rights activists were attempting to tell the full story of St. Augustine. Namely, that the city was — and had always been — multicultural.

At the center of things was Lincolnville, the historically black neighborhood established by freedmen after the Civil War (ergo, Lincoln-ville) in the southwest corner of downtown St. Augustine. (It was initially called “Africa” by its residents and built on the dirt that Henry Flagler dredged from Fort Mose. The name Lincolnville came sometime in the 1880s, shortly after Flagler attempted to turn the neighborhood into subdivisions, but failed.)

A local dentist, Dr. Robert Hayling — one of the most significant grassroots civil rights leaders of all time, as David Nolan has it — went to investigate a Klan rally near Lincolnville in the fall of 1963. Hayling and his companions were subsequently beaten and stacked like cordwood, narrowly escaping before being burned alive. Later that year, hooded Klansmen shot up the Lincolnville neighborhood. One resident fired back, killing one of the so-called night riders. In the intervening months, St. Augustine received more national attention than it had in its previous 400 years of existence. Sit-ins and swim-ins proliferated all over the city. Notable segregationists showed up to speak.

[First] Civil rights activists clash with segregationists at St. Augustine Beach, 1964 [Second] Dr. Robert Hayling and Len Murray of the SCLC in downtown St. Augustine, 1964 [Third] Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leaving the grand jury in police custody in St. Augustine, 1964. All images courtesy of the Florida State Archives

Then, in the spring of 1964, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference arrived.

The Williams family house was across the street from City Hall at the time. Diana remembers the swim-ins at segregated pools and beaches turning violent. She recalls cars burning in front of their house, windows shattering, having to skip town with her mother and head north to Jacksonville. Jack stayed behind. He kept his gun shop open. Alongside a cadre of local men, he was deputized by the sheriff to control the riots.

On June 11, 1964, King was arrested on the steps of the Monson Motor Lodge on the bayfront for attempting to enter the segregated motel. Less than one month later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law.

Jack was already a decade into his research of Fort Mose. In 1968, he bought the property.

Diana cuts through the static concerning her father and his legacy. She laments how he was treated, the fact that he was never adequately reimbursed for his efforts, and the disappearing act performed on his legacy. But the seeming irony in his secretly being Mose’s guardian is not lost on her: “That’s the heart of the story,” she says.

Jack’s son Dana, on the other hand, offers no equivocation.

“Dad regularly had breakfast with the head of the NAACP,” Dana says. “What really happened when he tried to sell the property was that people started finding excuses to criticise him. Politicians and journalists accused him of being racist, but I never saw that.”

Dana is also an antique weapons specialist and a historical pedant with an encyclopedic mind. The elder of the two siblings, he was old enough to assist his father on several research trips across Florida and into the Caribbean, padding his father’s extensive cache of colonial artifacts.

“It is a very difficult subject for me and my sister. He was very poorly treated. He spent nearly all of his time and money on Mosa,” Dana says. “And after all that, the state tried to keep his artifacts, too, but the judge ultimately ruled that they belonged to Dad.”

Dana is the executor of his father’s trust, which contains remarkable “curios and relics” — not just from Mose, but various periods throughout colonial and early American history. The artifacts Dana references were those from Jack’s early digs, some of the only material from Fort Mose that wasn’t lost, eroded, or submerged underwater. These were the trappings and debris of everyday life: rum bottles, plates, pipes. The most remarkable find was a silver St. Christopher’s Medallion, a dime-sized amulet Deagan called “the most evocative” for representing the accord with Catholicism that runaway slaves were forced to broker in exchange for their freedom.

St. Christopher's medallion found by Jack Williams on the site of Fort Mosa

Many of these same artifacts, including the medallion, are now on display in the Visitor’s Center. But they are replicas. The originals belonged to Jack until his death in 2011, at which point they were inherited by Dana.

“Yep, they’re all boxed up right here next to me,” Dana says, taking debit of his storage unit.

Shortly before he died, Jack lent the University of Florida some articles from Mose for research. Once he was gone, Dana had trouble retrieving them. They were eventually returned, not before being copied, Dana claims, without permission.

“Do you have any plans for them?” I ask.

“You know what, I don’t really know what to do. You can imagine the state hasn’t left a great taste in my mouth,” he says.

There was no great windfall of artifacts to begin with, so the idea that there are yet more materials in the hands of private citizens seems to appeal for more attention than it has been given. The replicas at the Visitor’s Center do not masquerade as originals, but there is also no mention of where those originals are held, or if they exist at all.

The scarcity of information about the chapter before Kathleen Deagan arrived, and what brought her there, was not coincidental. Luis Arana, the Historical Society Trustee and historian for the National Parks Service when it approved the sale to Jack Williams in 1968, admitted before he died that this recommendation was the worst mistake of his career.

As a result, Jack’s name is neither seen nor spoken by anyone affiliated with the park and mentioning it within Historical Society walls will certainly not curry favor, even though the staff today cannot be held accountable. Just about everyone besides David Nolan and Jack’s family balked at the mention of the irascible and unwitting hero of Fort Mose, a man said to have the suspicious and unsustainably lofty conceit of “being very protective of truth in history” by his daughter, who lost a large portion of his adult life in pursuit of it.

In an interview after the trial in 1989 that had been filmed by a local TV station but apparently never aired, Jack said: “Now that this trial has gone down, anybody that has a piece of land which they think has historic value, if they have any sense at all, they’re never gonna tell the State of Florida about it. This [precedent] will hurt the cause of history and gaining historic knowledge in the future.”

It’s hard to say precisely what Jack wanted, material or no, in exchange for all that time, money, and energy spent on these lost articles of American history. He said his drive was never monetary, but he still deserved a fair price for the land, not to have the state employ the machinations of eminent domain to confiscate it. He griped until the bitter end. But possibly no reward would have sated the more abstract dilemma — reaching the end of the road, having no place in the present. An old man resigned to his room of ancient things.

JACK WILLIAMS WITH OLD BOTTLE 2003, Photo by WALTER COKER

There was one other anecdote about Jack Williams I heard from Walter Coker, the photographer assigned to Jack’s infamous Folio Weekly profile. This was the only thing he remembered of their encounter, and as I looked back on Jack’s life, the story began to emerge as an ideal and aptly plaintive summary.

Coker visited Jack, then an old man, at his home downtown, where he posed with some of his artifacts.

“I don’t remember too much about the guy,” Walter begins.

This was in 2003, shortly after an embittered Williams received the Aviles Award from the City of St. Augustine, which recognized his role in the discovery of the fort. The gesture was regarded by Jack and his family as glib and perfunctory, intended to grease the wheels for loaning some of his artifacts to the state.

“He had all kinds of artifacts,” Coker recalls. “And he wasn’t afraid to pose with them. But he had the shakes. And he was picking up all this stuff which he wouldn’t have been handling without me there taking his picture.

“At one point he pulls out this clay pipe,” Walter says. But the pipe wasn’t related to Fort Mose, most likely one of Jack’s many priceless Native American relics. “All the sudden, he just dropped this thing, and it shattered.”

Walter was stunned. He felt loosely responsible, but could only stand there and watch Jack as he hovered over the broken shards, cursing to himself.

Jack wasn’t wrong to say that his case will hurt the cause of history, but perhaps he missed the point that it was never safe to begin with. As Walter Benjamin once said, “Only a redeemed mankind receives the fullness of its past.” Only then will “its past become citable in all its moments.” Ownership of land is tantamount to ownership of history, subject to the vagaries and temperament of the one holding its deed. Presumably, redemption does not come in the form of fair-market prices paid on demand. Nor is it the result of all historic landmarks being corralled by bureaucrats. Had the case been decided in Jack’s favor, the cause of history would still be injured. The cause is clearly unwell.

And yet all of this conjecture obscures the fact that — if he hadn’t been blithely handed a piece of history by the organization nominally entrusted to protect it — Jack would have never found himself in court with the state to begin with. David Nolan says the Historical Society gave up the land because black history was a toxic subject during the 1960s. Although it seems plausible, Dana Williams says there’s just no evidence to back that up.

In the story of Jack Williams, one gathers a sense of St. Augustine as what it appears to have always been, at least since statehood: a city in deep turmoil, full of squabbling historians, with so much to be proud of and to preserve, so much that has been invented for effect, other parts it might like to bury, and an ultimately loose grip on the controls. It was not a proud moment for anyone involved. Not even the dead. In this story, the likes of Francisco Menendez, Zora Hurston, Robert Hayling, and Irene Wright — who should have been the principal figures — play second fiddle.

After the state won Jack’s land, the Florida Park Service refused to buy any of the adjacent property. The surrounding area was incorporated in the original settlement. Rundown motels and creekside estates sit on what were the pastures and farmland that supplied food. The Fort Mose defensive line, across U.S. 1, is now a Winn-Dixie.

“Welcome to Freedom” reads the official Florida Parks Service pamphlet doled out at the entrance to the park. The bathos of this statement — printed in a tiny 12-point font — encapsulates the whole embarrassing, clumsily handled ordeal.

With all adjoining land privately owned, and the remnants of the forts half-sunken in an inaccessible tidal marsh, experiences are now limited to observation decks. Two narrow boardwalks jut out over sawgrass to overlook the respective sites of the first and second fort.

A placard on the railing reads: “Human actions such as dredging, canal construction, and development contribute to the changes in sea levels.” As Carl at the Visitor’s Center said, it began with Henry Flagler, who took the dirt underlying Fort Mose and used it as the foundation for his beaux arts Alcazar Hotel downtown, which has since been converted into St. Augustine’s City Hall.

One of two narrow boardwalks overlooking the respective sites of the first and second fort.

In the distance, the Vilano Bridge stretches over the Intracoastal Waterway to a span of the Atlantic coast lined with beachfront homes — vacation homes that remain empty for most of the year. They waver over the ocean, ever perilous. After Hurricane Irma, their spindly wooden staircases and balconies were deposited in crumpled, contorted piles on the beach like giant dead spiders. One house altogether tumbled off of the dune and into the water. Every day, the dunes seem to lose a little more sand, and the tides creep that much closer to the tarmac. City officials want a bigger seawall to rescue this coastline, the edge of the New World, from a force intent on washing it away.

For now, the glades surrounding the Visitor’s Center are quiet. Moss dangles from drooping oak limbs like threadbare rags; the silky gray bromeliad is the fort’s namesake for a good reason. Runaway slaves and Indians would often hide from slave catchers in beds of it. A line of teetering pine trees separate the park from nearby houses and dull the traffic noise. There is only Carl, his volunteer, and the birders. The latter have flitted off somewhere behind the scrub line. In their absence, a finch jumps unremarked from limb to limb.