With music venues shuttered, musicians across the South face huge losses — but from young to old, many can’t help chasing the notes that might sustain us.

Story by C.H. Hooks

Ever since Covid-19 threw life into a tailspin, my office has been my bedroom floor in my home in coastal Georgia. I emerged one day to take a walk and found that my 5-year-old had taped hand-drawn posters to the front window of our house. One read, “Come see Brer drum.” The other was a picture of him, stick-figured with a giant smile on his face, behind his set of drums. He had decided to put on a live show from our front porch.

My son was one of those kids who banged on everything, so we got him a plastic set of drums. He destroyed them, not in the traditional 2-year-old’s way of breaking plastic things, but by playing them until they fell apart. We upgraded him to a junior set when he turned 4. He was taking lessons from a local musician until the beginning of March. Now our calendar, like most people’s, is completely clear.

It’s easy to take live music for granted, the unifying feeling that flows through the company of the community experiencing it. But now, live music has stopped. With bars and concert venues forced to close, and festivals cancelled, musicians are at home with their families. For many, those cleared calendars meant the cancellation of shows that were their livelihoods.

By choice, I’ve lived in cities around the South where music is essential to culture (Austin, Savannah, St. Augustine). I’ve witnessed as friends worked in all facets of the music world. It’s important to my writing: I have music playing when I write. I write the characters in my stories to specific songs that I feel best embody them. If the music stops, many things stop, including the paychecks of musicians and those who work around them — the people in the background of the business.

One of these people is my friend and neighbor. Josh Giles manages bands, and over the last few weeks, has seen his industry slow to a halt. We have had more time for drinks, at a distance, during this time. In one of our conversations, Josh mentioned how his artists have been affected. I had questions, so I chased down musicians and industry folk I hoped could answer them. When I was done, I had talked to 14 people who told me how their worlds have changed instantly. I asked them all the same question:

“Where do you find hope?”

Photo courtesy of GeeXella

Jacksonville based DJ and vocalist, GeeXella, found out through Twitter that their official South by Southwest event had been canceled.

“It was like I got my stamp of approval, then literally three weeks later I was like, ‘No!’” GeeXella depends on DJ appearances to supplement more consistent income as the program coordinator for Jacksonville-based nonprofit JASMYN. After learning of SXSW’s cancellation, the ripples continued to spread: a DJ residency at a local bar, appearances, parties, all dried up due to forced closures.

“I'm just putting hope into community right now. I see a lot of people really caring for each other in other ways which is super sweet. Especially for the queer community. I feel like we're already like little tender babies already. One of my friends — one of my really dope friends — she's a nurse in Chicago. She just sent me money, and she's like, ‘Hey, like I know this time is hard for you right now, I know you’re a musician, I know you work at a nonprofit. Here’s some coin for you.’ And so that was really dope. I took a little bit of that and sent it out to my little queers and let them know, hey maybe go buy you a drink or buy you a sandwich or whatever you need for right now. That's where I'm putting my hope: community, because I feel like that's what's going to help us get through this.”

An unexpected homecoming in the middle of a tour feels like a step into the unknown. Hours after Nashville singer/songwriter Nikki Barber and her band, the Minks, played a hometown show at Basement East in March, tornadoes wrecked the bar. Despite the ominous kickoff to their tour, the Minks continued, only to land in New York City amid the uncertainty of COVID-19’s spread.

“We had just played in New York City at the Knitting Factory the night before … and we were going to go to D.C. when I got a call that morning that all of our shows except for DC, had been canceled and they were thinking the DC show is going to be canceled too. So we're stuck in New York.” The Minks were left with a decision. “Do we start driving down to D.C. or do we stay here?” Ultimately, Nikki returned to a rebuilding Nashville, and to her part-time job at Duke’s. By March 15, Duke’s and all of Nashville were shuttered.

“I feel like so many people are actually using this time to be creative,” Nikki says. “Whether it be writing a song, making a good meal, writing stuff down in their journals for the first time in two years — I feel like there's going to be a rise in the creative world, kind of like a renaissance in a way. That gives me hope in thinking that that's how we're going to cope from this and take from it.”

Music has already adapted.

Nikki Barber. Photo courtesy of The Minks

Our first Friday night of social distancing, my family streamed The Luck Reunion. We sat down for spaghetti dinner at the coffee table in our den (a risky idea at best) and pulled up streams of some of our very favorite artists as they played live from the comfort of their own living rooms. There is an intimacy to live music, a rawness and tender vulnerability that endears. We didn’t watch, but we listened.

Nashville-based owner of the public relations company IVPR Maria Ivey, who handles Public Relations for The Luck Reunion, said the idea to transition from the physical festival came quickly. “Everyone kind of felt like they had the wind knocked out of them for a second and then quickly, in true Luck fashion, they kind of just pull themselves up and you just keep moving forward.”

A few days later, we watched throwback country musician The Kernal play via Facebook and Instagram Live. He took requests, and, from what I could tell, enjoyed the hell out of having an audience. We donated what we would have paid in ticket prices, without leaving the living room. I think Brer’s porch show idea came from watching The Kernal play the live set.

I asked singer/songwriter Joe Garner (The Kernal) how it felt on his end. “It feels like we were connected with all these people. Just knowing, without even looking at the comments, that those people were out there holed-up. It felt pretty-much like the stage. It's kind of funny how that works, but I think people are starving for it right now, too. It's pretty interesting, especially with how new this stuff is. It would be a much different situation if we didn't have the opportunity to do the streaming thing. It kind of keeps everybody rolling.”

With the way that life feels so accidental and out of control these days, perhaps music (like art and poetry) becomes, again, the thing to rely on. It’s a well in which to pour our frustrations, our emotions, and a space to seek out the connections that we need to continue to feel alive in our isolation. It is, as always, something to share, a tool for the discovery of our lost friends and favorite artists, and now, even more, a place to find our commonality.

Photo courtesy of Caleb Caudle

Nashville singer/songwriter Caleb Caudle was anticipating the release of his new record, “Better Hurry Up,” and had a tour planned. “Our Yeti party got cancelled at South by Southwest. When that happened, I was kind of like, ‘That’s a lot of money, and people don't really mess around with a lot of money unless it's really serious.’ And so I was preparing myself then. I wasn’t prepared to lose the entire tour, and I was definitely not prepared to start losing parts of the European tour as well. … We were just like, ‘Wow, we've really planned a long time for this and put so much work into it, and now this is our new reality.’” Caudle said he will likely lose as many as 80 shows. “For an album release tour of that magnitude, where it's not only in the States but it's also seven weeks in Europe. It's like — those 14 weeks — that's like my almost entire year’s income. So it's been a pretty big blow to us. Obviously, we're very fortunate. We didn't have our house hit by the tornado, and there's many people who have it worse off than us. So I don't want to ever sound like I'm complaining.”

“I think everyone's just trying to figure it out in real time. And sometimes it's easy to kind of slip into that zone where you're so focused on your own situation and you can't see out.” As for how he’s holding on to hope, “Honestly it's just the kindness of humans. Just seeing folks help out each other. I just feel like there's a lot of people out there who have the means to do that, and we've seen it in abundance in our situation. I've seen it across the board. We're always all in this together, so it's nice to see people take that a little bit more seriously.”

I spoke with Joe Baker, manager of Killer Mike and co-manager of Run The Jewels, from his home in Sandy Springs, just outside of Atlanta. His wife and kids were down in Savannah with family. He and his team had been on the west coast preparing for Run The Jewels’ upcoming album release and tour when word began to spread of a possible shutdown. With an industry-wide stop, everyone is affected.

“We were actually in L.A. when everything first started,” Baker said. “We shot a video and we did a photo shoot and then started rehearsing. It was just a lot of talk. You know text messages from friends at CNN asking me, ‘Are you shutting down Coachella?’ I was like, listen, I don't know. I haven't heard from my booking agent yet.”

Baker described the ripple effect of cancellations. “The whole crew: the tour manager, the sound guy, the merch guy, the lighting guy. Those people depend on us moving in order to provide for their families. It’s affecting everybody. Mike and El-P are going to come out of their pockets to assist the guys with anything that's needed. I mean we're family, you know, and they would travel together. … They're not just employees, they're a part of the team.” As for the hope question, “I think the hope is that everybody would be a little more appreciative of things that we lost during this time.”

Run The Jewels. Photo by Zach Wolfe

“The whole crew: the tour manager, the sound guy, the merch guy, the lighting guy. Those people depend on us moving in order to provide for their families. It’s affecting everybody. Mike and El-P are going to come out of their pockets to assist the guys with anything that's needed.”

– Joe Baker, Co-Manager of Run The Jewels

For recording artist and musician William Tyler, the approach of the virus, the cancellation of Big Ears Festival, and a gut feeling led to the desire to be closer to family in Nashville.

“I really had almost the whole calendar year booked up till September, and then everything, within a week, everything went away.” Tyler said he thought, “I'm just going to get as many things as I can fit into my car, and I'm just gonna drive back as quick as possible and try to be as careful as possible because I don't want to be stuck.” He drove the 2,000 miles back to Nashville from Los Angeles. “On the local level I would say I feel like people really are, in my circle, are just being really kind and patient with each other, and on a global level I think It's putting everything into perspective in a way that we really really needed.”

Salisbury, North Carolina based singer and performer Pat “Mother Blues” Cohen has felt a larger dislocation before, when she moved from New Orleans to North Carolina post-Katrina. Since that time, she has continued to feel loss. She watched her house burn to the ground, and she lost two brothers to strokes. She’s picked up the pieces each time.

“I’m thankful, I look at everything that has happened as a blessing,” she said. “I have my life, my health, my strength. I have a refrigerator full of food, I have a freezer full of food. I have about eight cases of soda.” She laughed. She’s spending time at home with her Boston Terrier, Mr. Bubbles. “I’m not sitting around thinking about being broke. I am. But I’m not thinking about it. When I lost everything before, for an entire year I cried every single day. And it didn’t accomplish anything by doing that. I still had the same problems, but only I felt worse from all that crying.”

photo courtesy of Music Maker relief foundation

“Do something nice, keep moving, don’t listen to or get upset by foolishness. You can’t let anybody influence how you feel. Stop all of this craziness. Life is too short. We’re wasting valuable days being upset and being afraid. Think about something positive, what good thing can you do. What could you say yes about? Say yes to somebody. I’m going to constantly take care of myself.”

- Mother Blues

When I asked about hope, she offered good advice.

“Do something nice, keep moving, don’t listen to or get upset by foolishness,” she said. “You can’t let anybody influence how you feel. Stop all of this craziness. Life is too short. We’re wasting valuable days being upset and being afraid. Think about something positive, what good thing can you do. What could you say yes about? Say yes to somebody. I’m going to constantly take care of myself.”

Then, Mother Blues laid down a one-liner I might tattoo on my arm: “We already have a situation here, so why make it worse by stinking-thinking?”

When I spoke with Joe Garner from The Kernal he was taking a walk outside of his Jackson, Tennessee home. “When I'm home from tour I'm normally trying to pick up work, like carpentry work and stuff like that — but being home now, I'm not having gigs and not having work, just wandering around and seeing the blooms and stuff. The world seems in so many ways like it’s stopped, but it's not. The actual world is going, and just being reminded of how unshakable nature is. It puts a lot of things in perspective. It's so easy to kind of get your blinders on and, ‘we're going to put this record out, we dropped a single, we got to get some tour dates, we got to make some connections, we got to get some art work.’ There's always something going on that kind of keeps your mind attached to all the society stuff. This thing just reminded me more of what it is to be a person, living in the world just like we have been for millennia.”

But how do we handle the uncertainty of this situation, as the timeline creeps out?

When Nashvillian singer/songwriter Sean Scolnick — Langhorne Slim — rode to the airport with an Uber driver last month, they got into a political discussion and the pendulum theory came up. The idea that eventually (and hopefully soon) the pendulum which had recently spent so much time hovering into the negative, would need to swing positive. Slim says the driver brought new perspective to the theory. “And he (the driver) was like, ‘I like that theory because it applies to a lot in life. The thing that people don't think of, or realize often, is that one never knows where the pendulum is actually fucking at, and they might think that it's at its apex, but you really don't know.’ And that's really stuck with me, because that's been so true in every situation, not just the political stuff, Trump stuff, tornado, global pandemic, everything...I feel like, well it's got to swing the other way because you can't get any further up at this point, And I’ve got to keep that in mind. It's just like, ‘Oh no, shit just keeps getting crazier and crazier.’ I tend to get the feeling with this particular situation it’s only going to get a little weirder before it gets less weird.”

I asked Slim, “Where is the crux for this pendulum? Is it in the cosmos?” The pendulum was already swinging far enough for most Nashville residents after the tornado hit east Nashville in early March, two weeks pre-lockdown. Slim lives only a couple of blocks from neighbors whose homes were lost. The community came together for mere days only to be forced apart into isolation.

Photo courtesy of Langhorne Slim

The repercussions and uncertainty extend deep into the community — into the service jobs, the hotels, the institutions. The ecosystem surrounding music is robust, but delicate as well. Some festivals have existed long enough that the communities are somewhat dependent on them.

Maria Ivey (IVPR) explained how the 30-year-old MerleFest brings 80,000 festival goers to the small town of Wilkesboro, North Carolina. The community has grown to count on the revenue. MerleFest is also a fundraiser for the local community college. Its cancellation will affect the town heavily. “Sagebrush is a chain steakhouse in the parking lot of the hotel they put us up at, and I remember last year the server saying she makes three months of rent during four days that MerleFest is in town.”

My neighbor Josh Giles owns Small Fry, Inc ( Management for The Minks, The Kernal.) “If this goes on and on, we might not have our shows in 2021. Are these venues even going to open up right now? If it goes on for three or four months, there’s going to be a backlog. We’re trying to plan and coordinate all this stuff. If it keeps getting pushed back, they’re going to have to let go of employees — which, they already are — then let go of leases. Are the venues, which are already running paper-thin anyway, going to be there in three, four, five months? We have to take a proactive approach.”

Yet, Giles remains optimistic. “When things are disrupted this much, it can create opportunities. It forces people to try new things, become even more creative. Even try old things for the first time. It’s inspiring to see people helping each other out. Not just fans supporting artists, but artists supporting venues and sound engineers, bartenders, etc. Which, to me, is what we have to have.”

My kids talk to other neighborhood children through the fence and cry when they’re told that they can’t play tag with them — something that was totally commonplace a few weeks ago. But there’s some power in controlling what we can. There’s some control in accepting our reality. If artists attempt to harness the entropy, perhaps they can ride the collapse.

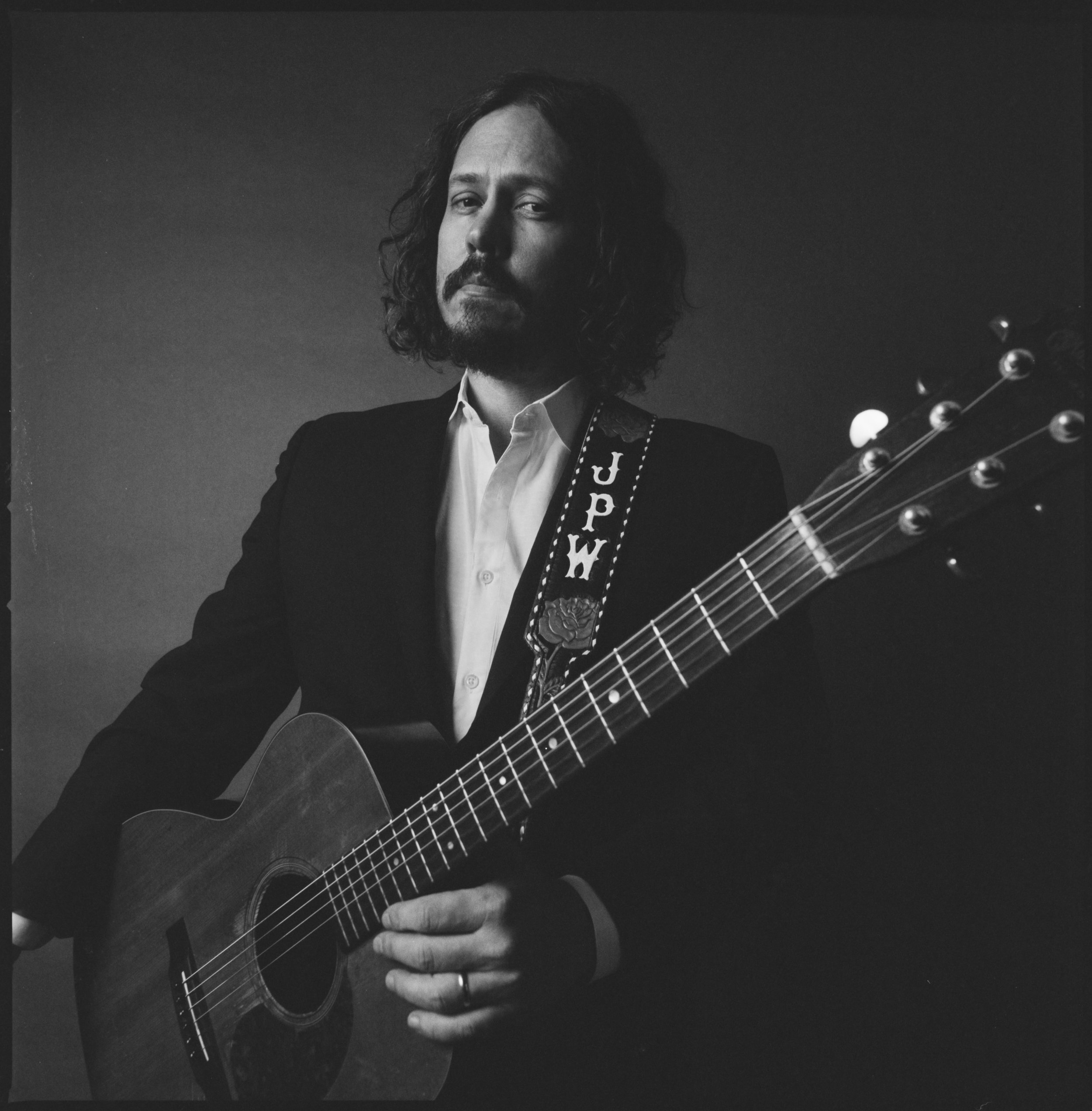

Photo courtesy of John Paul White

“We may get a lot of sad songs out of it. Cause you let musicians, song writers, creative folks sit in one place for too long — you know, our job is to dig in there and open a vein and get at the root of what's bothering us and what's bothering other people and help them articulate it — if we sit here with too much time on our hands they'll probably write some powerful songs.”

– John Paul White

When I spoke to Singer/songwriter John Paul White (also a partner in Single Lock Records) he’d left tour to be at home with his wife and three kids. He’d found some peace in the swing away from compulsive productivity. “As much as I hate losing touring and losing income and not being on the road and doing what I do and what I love — I am really enjoying being home with my kids and my wife...most of us don't get that opportunity.” But he also recognized the realistic nature of musicians in isolation. “We may get a lot of sad songs out of it. Cause you let musicians, song writers, creative folks sit in one place for too long — you know, our job is to dig in there and open a vein and get at the root of what's bothering us and what's bothering other people and help them articulate it — if we sit here with too much time on our hands they'll probably write some powerful songs. You know, there could be a lot more deep emotional songs about isolation, loneliness, and being anti-social and being forced to be anti-social. So there could be a lot of heaviness coming out of this next batch of stuff from me and from all of my friends. On one hand, as a big fan of sad songs, I'll probably eat it all up. On the other hand, once we write the song, that shit doesn't go away. We’re still dealing with it — all that stuff. So I worry a little bit about my buddies.

My hope is just people in general. Everybody’s being respectful and staying in line and going to the grocery store and people for the most part are respectful and you know checking up on each other. And you know, ‘here I've got two of those. Here You take one, because I know there's not any left.’ And they’re doing the right thing. Maybe I'm turning a blind out to the idiots that are stirring the pot, but I think at the end of the day we're going to be a changed nation and I like to think we’re going to be a better one for it.”

Langhorne Slim has also embraced optimism to temper the uncertainty. “There are possibilities in this that can truly be beautiful. Obviously we're being forced to slow down — but I feel within myself an ability to slow down. I feel some of the callouses coming off, some of the hardness or the negativity. I'm hearing from friends that I haven't heard from in a long time. People are calling. People are actually picking up their phone and wanting to talk.”

On the far swing of the pendulum, we think of how to help.

Singer/songwriter MC Taylor of Hiss Golden Messenger has embraced the opportunity to give back to his Durham community. On March 27th Hiss released a live album to benefit the Durham Public Schools Foundation. This will help public school kids Durham, NC, continue to receive lunches while out of school. “The way that this thing is working in kind of an existential sort of cosmic human connection level is pretty fascinating and in a lot of ways really cool to me despite the pain and hardship that is causing. It seems to me that people in their own houses are connecting in ways that we had maybe forgotten about and people are using social media as a way of connecting that feels interesting to me and sort of progressive, you know? Emotionally progressive.”

Maria Ivey. Photo courtesy ivpr

Maria Ivey wanted to be more involved in helping musicians in need. “My husband and I have been cooking a lot. And it’s so interesting to read the story behind the recipe. I put out some feelers to artists and friends in the industry and said, ‘I’m going to put together a cookbook of people’s family recipes.’” She quickly assembled a stack of recipes from artists and industry people including, Bobbie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, and Elizabeth Cook. Once bound and printed, sales of All The Thyme In The World will benefit the Music Health Alliance, a Nashville based organization connecting musicians to healthcare.Tim Duffy, co-founder of the North Carolina-based Music Makers Relief Foundation, said the artists his nonprofit have served for 25 years “are living on the complete fringe anyway.”

“A majority of them are in their late 70s, in their early 80s, up to the 90s, with heart conditions, asthma, diabetes — so they’re the highest risk, really. The ones that have work, that do work — we book about 500 individual performances every year — all that work is lost in the foreseeable future. From spring through June, the entire spring is cancelled. And it seems like the summer as well. And all their side gigs are cancelled, even humble gigs like playing in churches, nursing homes and small bars in their community. When your income is, at best, $12,000 a year, from a Social Security check or something, and then you lose playing the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival where you're going to make $2,500, that's a huge loss.”

Music Makers’ staff is now working hard to make sure their partner artists get the information they need to stay safe. They are also scheduling grocery deliveries to cut back on the artists’ forced interactions with the public.

“I see hope with all the generosity of our donors,” Duffy said. He had just spent two days on the phone meeting a $50,000 fundraising goal. “I was very amazed. That's what makes us unique as Americans. We really do rally, and we’re very generous, and people really do want to help. I've traveled around the world. This is a unique American quality that we do: band together. From my seat, seeing the support coming in and having a staff that can reach out and be a voice and a friend to the artists that we serve — they appreciate the love, they appreciate the help, they appreciate the groceries, and the guidance to get through this. So that's the side of the river I’m on.”

Music Makers supports the kinds of artists who, at this moment in our crisis, feel the most precious to me. COVID-19 puts the South’s aging musical pioneers and standard-bearers in grave jeopardy. That threat seemed to grow in my brain — as relentlessly as the virus itself — during the weeks I worked on this piece. I first learned about a family friend with pneumonia and another friend waiting on test results. Then similar news came from friends on both coasts. A week into April, I watched — on YouTube — the funeral of a woman who helped raise me. Her family was unable to travel and had to gather virtually from around the country. That same night, after my wife put the kids to bed, the news came that one of Appalachia’s (and America’s) most beloved songwriters, John Prine, had succumbed to the virus, his immune system weakened by his two victories over cancer. We sat on the floor of our home office and watched Prine’s NPR Tiny Desk concert. Neither of us could keep it together through even the second song, “Summer’s End,” which reminds us repeatedly, “Come on home, come on home. You don’t have to be alone.”

Freeman Vines (background) and Tim Duffy. North Carolina, 2018 [Photo by Simon Arcache]

The losses now are overwhelming. We all feel the unimaginable shock of losing so many, so quickly.

This week, the music community is still reeling. After losing treasured artists like Prine, New Orleans’ jazz icon Ellis Marsalis, and more, we wonder, naturally, who are we going to get to keep? How can we best protect them?

These older artists, I’ve concluded, share the life experiences that we most need to draw on. They’re qualified. We have depended on them to help us face our personal struggles and fears, our loneliness and doubts. Now, we ache to hear Prine break down the small moments and struggles of this fight for our lives, but these qualified voices are most quickly quieted by the virus itself.

Singer and performer Sam Frazier Jr.’s voice rings heavy with a lifetime of experience. One of Music Makers’ partner artists, a self-described singer and entertainer, Frazier is a blues musician with roots so deep in the Alabama soil he can still pull from the trailblazers before him. His concerns were simple, though at 75 years old he’s arguably one of the most at-risk individuals I spoke with.

“I’ve been doing what the doctors say. Been going to dialysis every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. And I haven’t been performing ’cause everything is closed up. Which is good, because of the virus. I’ve been staying around the house taking it easy, taking medicine, and doing what the doctors tell me to do. And that’s why I’m still going strong. I’m doing pretty good right now.”

He praised the Music Makers Relief Foundation profusely. “Music Makers was the strongest break I’ve had. Music Makers has been here for me. They send me groceries. They take me to the studio and record me. They encourage me with my music and do things for me when I need something. Music Makers has always been right there.”

I asked what gave him hope, and he began by spelling the word back to me.

“H-O-P-E?” Frazier asked me. “I’ve been some of everywhere. So many stops along the way. I’ve been around a long time, and I thank God for every minute of it. That’s my hope forever. That I could make some of it come true, for me. I hope to go farther than where I am. I hope to get where people will know who I am before I leave this world.”

~ Watch Sam Frazier Jr. ~

Sam Frazier Jr. put my recent dragging days into a new perspective. I fear my own entitlement, that I have somehow owned my timeline, that my previous bitterness over isolation is total bullshit. I’ve spent it within four solid walls with my family. I write books. I teach college. What a baby. I look in the mirror for the first time in a long time. I realize the reality I exist in was the only one I noticed, until now.

While I spent my days having these conversations and taking in these stories, my son Brer was practicing for his front-porch session. There was nervous energy around our house. Thankfully, he drummed our couch cushions while I was on phone calls. He woke up early in the mornings to talk to me about his setlist.

Brer’s show was on a Thursday in late March, before our statewide shelter-in-place was issued. I moved his drum kit to the front porch, tightened the heads, then looked around the empty streets and worried for a moment about the noise. I remembered that friends down the block had told me they heard Brer play from the kids’ bedroom sometimes, but also that a noisy neighborhood is one that is still alive. Brer sat down and we checked his setlist. My wife started the livestream for friends. As he started to play, a car or two slowed out of curiosity. By the time he got to the third song, “Otter Wants Salmon,” neighbors were dancing in the yard — several feet apart. His smile matched the anticipatory picture he’d drawn. He was happy to make music for people any way he could. He gave us an encore of “Port-Starboard” and dogs barked and neighbors clapped from the street.

After the show, we re-upped drinks and walked to the park. The world could be falling apart, but the weather is beautiful. The kids raced around and looked for owl feathers. I asked my neighbor Josh “What’s the future look like.”

“Haven’t been there yet,” Josh said.

“Will there be music?”

“For sure.”

C.H. Hooks is the author of the novel “Alligator Zoo-Park Magic” (Bridge Eight Press, 2019). His work has appeared in publications, including American Short Fiction (Bourbon & Milk), Burrow Press (Fantastic Floridas), and Four Way Review. He has been a Tennessee Williams Scholar and Contributor at the Sewanee Writers' Conference, and attended DISQUIET: Dzanc Books International Literary Program. He is a Lecturer at the College of Coastal Georgia.