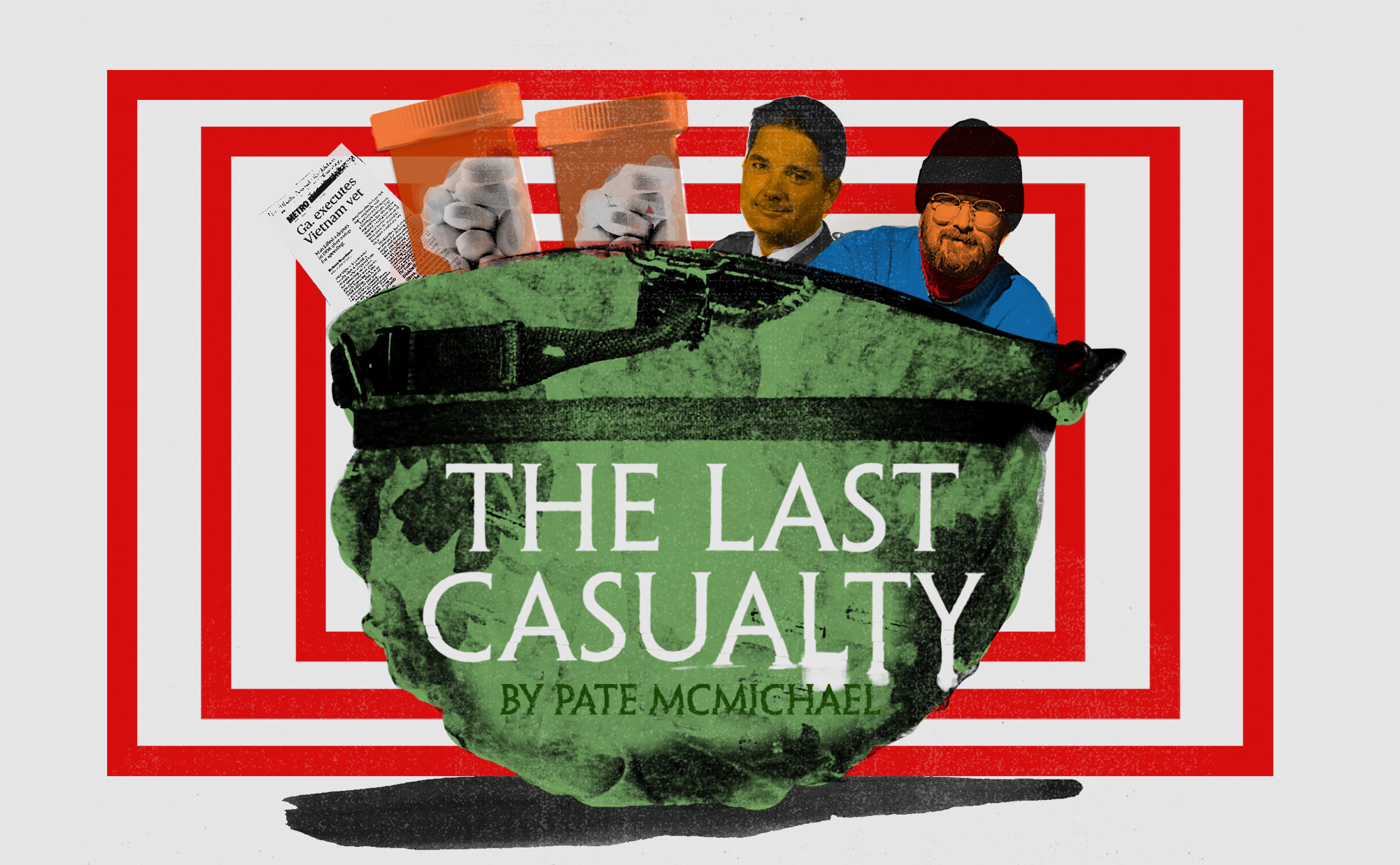

Yesterday, veteran journalist Pate McMichael took us into the life of Andrew Brannan, a decorated Vietnam veteran who was the first person executed in the United States in 2015 — 17 years and one day after he shot and killed Deputy Sheriff Kyle Dinkheller in Laurens County, Georgia. Today, we follow Brannan's troubled life after Vietnam as his escalating struggle with PTSD leads, almost inevitably, to the gates of Georgia's death house.

By Pate McMichael

Like most soldiers sent to Vietnam, Andrew left behind a girlfriend. Her name was Pamela. Her parents lived on Club Drive in Stockbridge, just a few houses down from the Brannans. As children, they played together in his fort but grew apart as the Brannans deployed around the world. But when the colonel finally retired, Andrew and Pamela, now in high school, started dating.

Pamela visited Andrew twice at Fort Bragg just weeks before he deployed to Vietnam. On the first visit, he showed her around the base and talked proudly of serving his country in a time a war. But during the second trip, he let her in on a secret.

"He made it clear that he wanted to avoid participating in combat, and he talked a lot about the two of us going away together to Canada," Pamela later recalled. "The more we talked, the more Andrew seemed to despair over the situation and the more I knew that going to Canada was not just a passing idea. Avoiding the war by going to Canada was something that he had given great thought to and something that he really wanted."

Then he proposed. She felt flattered, but said they should wait. She had two years left in college, and she knew that he would never disappoint his parents, particularly the colonel, by going AWOL.

"To even voice these concerns to anyone in Andrew's family would have certainly provoked a strong and negative reaction from his father," Pamela recalled, "and Andrew would go to great lengths to avoid upsetting or disappointing his father."

She wrote to Andrew during the fall of 1970, as he patrolled downrange in the jungle, but her letters were not answered, even after Andrew was reassigned. She didn't see him again until he returned home holding a peace sign shaped like a teardrop. He placed it in her hand, a souvenir from Vietnam.

"We spent time together, but Andrew was very different than he had been before the war," Pamela recalled. "I tried to get him to open up to me about anything — his daily life, his family or his experiences in Vietnam. No matter what I tried to talk to him about, he remained defensive. I became very confused about our relationship, and eventually we stopped seeing each other." Looking into Andrew's eyes, she noticed something missing. "After Vietnam it wasn't just that Andrew was reserved," Pamela recalled. "It was that he didn't seem to want to have anything to do with anyone."

Back in Stockbridge, Andrew moved into a party house with two buddies, Hank and Doug. His roommates were the personality; he was the furniture. They worshipped bands like Ten Years After and Traffic, the Beatles and the Stones. They smoked grass and threw wild parties, worked on muscle cars and chased free-spirited women. On more chill weekends they would set up sawhorses to play giant board games like Afrika Korps (the German invasion of North Africa during World War II). Andrew loved to waste a Sunday that way, running supply lines in an epic battle.

He lost respect for the war, but not the military. With enthusiasm and passion, he stayed in the Army Reserves and completed his yearly service duties with high marks. But outside the wire, he struggled to fit in. He commuted to college classes while balancing shifts at Hercules, a utilities manufacturer in nearby Covington. He couldn't take the monotony of a regular schedule, so he asked for rotating shifts, preferably at night. Then, after a few failing semesters, he dropped out of college altogether.

He was sitting on the couch one lazy afternoon in 1972, when a young woman named Lynne Perry paid a visit to the party house. She was a champion horsewoman — lean, tan, and Southern, but with a Joan Baez, "Give Peace a Chance" quality. When she appeared out of nowhere, Andrew smiled sheepishly and exchanged courtesies. Then he stood up, took her hand, and danced to a track from Leon Russell and Marc Benno's new record, “Asylum Choir II.”

Lynne and Andrew didn't exactly fall in love. The relationship started as a business proposition: Lynne needed a dependable husband in her life to convince the owners of a stable that she could train their horses. Andrew needed someone low-maintenance who would give him the mental space to work on cars, study computer systems or just sit alone in solitude. On weekends, Lynne traveled the South claiming titles at prestigious competitions like the Dixie National Horse Show in Jackson, Mississippi. Andrew tagged along when he felt like it, but often, they lived independent lives.

"If I needed any help with horses, he was always there. He was always there for you in a time of need," Lynne recalled. "He was a good caring person. He was just so sensitive. Most people didn't understand that."

Lynne's father, a successful businessman in Atlanta, built them a home in Stockbridge. On the night they were supposed to move in, she received a call from her fiancée, who was down in Laurens County — where he later built the camp house and killed Deputy Dinkheller — collecting psilocybin mushrooms.

"Get the truck," Andrew said. "I can't fit them all in the M.G."

Lynne hurried south down Interstate 75 to help ferry those little psychedelic wonders back to Stockbridge. They dried them out with the bathroom heater, then threw an uproarious party. Andrew loved to trip on 'shrooms. It gave him an escape from the nightmares and awkwardness of everyday life. When relaxed and comfortable, he would cheerfully debate the universe, the circle of life and the supernatural. Lynne always viewed his modest drug use as a merciful escape into the cosmos, nothing close to an addiction.

"When Andrew was not being troubled, he was such a sweet and kind person," Lynne recalled. "He laughed. He liked it when it was a no-pressure situation."

They married in February 1975 at Plantation Manor Children's Home in Conyers. She wore a simple teal dress, and he sported a light-colored suit with a red shirt and tie. Lynne had been adopted at birth, and, as a teenager, spent many hours volunteering at the Manor. Orphans served as their wedding party, and not long after, Andrew and Lynne gave temporary shelter to a young teenager who had aged out of the system. But the honeymoon didn't last. A few weeks after the wedding, Andrew received a letter from the Army Reserves with the subject heading: "Nonselection for Promotion after Second Consideration." He had been denied promotion in the Reserves for the second time. No explanation was given, but according to the letter, Andrew should accept it as his discharge notice. Just like that, he was kicked out of the military.

That fall, Bobby died in a military plane crash. Bobby’s widow, Cathy, moved into the Brannan family home with three young children, the youngest two being twins. Cathy didn't always see eye-to-eye with Bob and Esther, so Andrew served as a buffer, on occasion letting her and the children stay with him and Lynne. To make matters worse, Bob and Esther put pressure on Andrew to start a family. They expected him to finish college and find a meaningful career. Now that Bobby was gone, he assumed the burden of satisfying their lofty expectations.

Andrew's mental illnesses progressed from that point forward. Under pressure or backed into a corner, he performed loud tantrums directed at Lynne. When she tried to confront Bob and Esther about his rage, they refused to believe it. She finally resorted to setting the telephone down on the kitchen table so they could hear Andrew yelling at the top of his lungs. Over time, he became physically, not just verbally, abusive. Several nights she slept outside in fear for her life, and during the fall of 1979, she filed for divorce, keeping the house and the horses. Andrew took the sports cars.

Hollywood, perhaps better than the Pentagon, knew what was happening to Andrew. In 1978, Director Hal Ashby released “Coming Home,” a blockbuster motion picture about the nation's indifference to the plight of Vietnam veterans. Medical journals started publishing studies about "post-traumatic stress disorder" as early as 1973, but the affliction was not officially acknowledged until 1980 in the third iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, better known as DSM-III. It took much longer for the VA to approve treatments for PTSD as fundamental to good medicine.

Andrew was one of millions whose mental trauma progressed untreated. After the divorce, he recommitted himself to learning and graduated from West Georgia College with a degree in geology and a minor in computer science. The following year, he secured a stressful job with IBM and somehow held it down until Sam committed suicide that summer. The combination of the two — the stressful job and the shocking death of his little brother — caused a mental breakdown. Andrew locked himself into a bathroom at his parents' home and refused to come out for several days. IBM terminated his employment, and the colonel ushered his last son into a local counseling center, then over to the Decatur VA.

In 1985, doctors diagnosed Andrew with a severe form of PTSD and declared him 10 percent disabled. Since the war, family members had found it nearly impossible to engage him in conversation, but after the breakdown, Andrew sometimes talked frantically — loudly blurting out the details of his mental illness as if reading from a script. These breathless conversations, though still extremely rare, usually segued into disjointed rants about politics or Vietnam.

Embarrassed by his instability, Andrew decided to withdraw from the human world. The limited income he received from the VA helped support what became a mini-career in long-distance hiking. From 1985 to 1989, he trekked thousands of miles across the nation's most grueling terrain. Using military training and mapping skills, he prepared elaborate care packages and plotted drop-off points along the way. Bob and Esther mailed his packages at prearranged times.

It must have felt like an epic tour of duty — sleeping outside, fighting off the cold, surviving on canned rations. His first journey — the Appalachian Trail — started at Springer Mountain in Georgia and ended atop Mount Katahdin in Maine. On Father's Day in 1985, taking a well-deserved and emotional rest at Hopewell Station in upstate New York, he wrote a letter home:

"This is a Father's Day card. I wish to thank you for being the being that means the most to me. You have set a good example which I only am now getting better at following. But I will keep on going. Better to keep on going than to stop. Yet I will never be as good as you, because you just keep getting better. I will always love you, as Bobby and Sam do, for it is just the way it is. So take care. I will, if you will."

In 1987, Andrew hiked the Pacific Crest Trail — from northern Mexico to the Canadian border. The year after that he may have been the first person to complete the Colorado Trail, a newly minted, grueling passage linking Durango and Denver. Then he was off to conquer the Wind River Range trails in Wyoming and the Olympic National Park trails in Washington state. He only stopped when the colonel asked him to seek more help for PTSD. Soon after, Bob was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

In 1989, the Decatur VA kept Andrew hospitalized for nearly two months. The treating psychiatrist felt sure his patient was a danger to society.

"He also states he is uncomfortable with people and feels a continual state of anger, and is afraid of losing control," medical notes read. "He experiences flashbacks and dreams of Vietnam, chronic suicidal ideation, frequent inappropriate laughter. A key event there was … he did not follow his instincts to take out a Vietnamese patrol, and the next day, when he and his commanding officer split the group into two patrols, his commanding officer stepped on a booby trap and was severely wounded. The patient feels guilt, as he felt the death of his commanding officer could have been avoided."

In the fall of 1989, Andrew entered a long-term PTSD treatment program at the Augusta, Georgia, VA. For the next seven years, he would continue intensive therapy, including a sixth-month, in-patient stint with other Vietnam veterans. One nurse reported the following: "Afraid of his rage. States his thoughts are sometimes very violent…. Feels a severe amount of survival guilt because he was an officer…. Problems with authority figures and social interaction are severe. States he knows that his future consists of living alone to prevent his rage from getting out of control."

In 1994, Andrew was diagnosed as bipolar. Up until that point, he had refused to take medication because he wanted to be a "natural person." Medical research shows that an unmedicated bipolar individual with severe PTSD is a ticking time bomb, so, after decades of suffering, Andrew was finally prescribed powerful antipsychotic drugs that kept him on an even keel but did not bring peace or stability. Friends and acquaintances all experienced bizarre and scary behavior from Andrew during his medicated years. He would get hyper and defensive without warning. He talked loudly and showed little self-awareness. The most chilling example happened at a Mexican restaurant in Atlanta. As Andrew and his friend waited to pay the bill, a police officer said something to Andrew that sparked an argument. The friend stood there embarrassed as Andrew berated the cop, brought up his Vietnam service, then somehow avoided arrest.

"The veteran does not make friends and spends his time alone trying to straighten out his thoughts and feelings," a VA psychiatrist wrote in 1995. "He has no patience and is easily upset. The veteran advised the examiner that he wanted to construct a bunker beneath his room. He stated that he is preoccupied by his Vietnam experience and still has dreams about it."

The highs and lows also brought out what may have been an alternate personality. In February 1997, Andrew told his psychiatrist that during moments of "giddy euphoria and sleeplessness" — typical of someone who is bipolar — he received great pleasure (or "hypomania") from "shaving off his beard" and "cross-dressing." His ex-wife, Lynne, experienced similar episodes during their marriage. In the bedroom, Andrew sometimes asked her to switch roles. She played along at first, but just couldn't get into it. She believes that Andrew had longstanding fantasies of being a lesbian.

In early 1997, the VA added a mood stabilizer to Andrew's medication regimen and reported encouraging results. But in the weeks preceding the murder, Andrew forgot to refill his medicine. He also travelled to Nevada to visit an old friend. While there, he purchased the M-1 carbine to scare off crows down at the camp house. In December 1997, he visited the Decatur VA for the last time.

"He was two weeks late in refilling his prescriptions in late November, early December," his psychiatric notes read. "During this time he ran out briefly and noted he was somewhat more irritable. However, he denied any episodes of physical violence. He related stories of how he narrowly escaped death in Vietnam, which was the first time he offered such highly emotional material."

In early January 1998, Lynne called Esther to check on Andrew. She was now remarried with a child of her own and wanted to invite Andrew up to the mountains for a visit. The bitterness of their divorce had ended when she came to Sam's funeral and forged a lasting relationship with Esther. Andrew picked up the phone on the day she called. He sounded excited, said he had other friends in the area from his hiking days, but in typical fashion, never showed.

The following Monday, late at night, Lynne received a startling call from their mutual friend in Nevada, whom Andrew had recently visited. He told her that Andrew had killed a police officer in Dublin, that he was on the run, and that the GBI wanted all his friends to be on the lookout. He might just show up at your doorstep.

A few days later, Lynne drove to Stockbridge to take possession of Moses, the orphan dog Andrew had rescued from the wilderness then abandoned without saying goodbye. Lynne ferried Andrew's dog to the foothills of the Appalachian mountains, supplied him with hearty meals and trained him to follow most orders. Andrew was on death row for a long time when he learned that Moses died of old age.

Life in prison, with no freedom and no hope for redemption, held little purpose. Andrew received the convenience of a private cell because of his mental illness, and the books he kept behind bars were a reflection of his singular obsession: The Vietnam Dictionary, Vietnam: A Visual Encyclopedia, and Vietnam Order of Battle. He passed his days listening to the Beatles, making collect calls to family, and walking alone in the yard while other inmates shot basketball. The state's most notorious killers dubbed him Missing in Action, or "M.I.A.," for short.

His appeal for a new trial failed just before September 11, 2001. It seemed futile to keep trying, but the spike in patriotism reminded him of that sacred oath he took in 1968. The respect and support the public extended to the military, as Operation Enduring Freedom began, ended four decades of public indifference. Andrew felt a moral and legal obligation to fight for his right to stay alive. Justice demanded that he be transferred to a medical facility.

Then the Iraq War began. Media comparisons to Vietnam seemed overstated, but Andrew followed it closely on the break-room television, as "shock and awe" liberations matured into stubborn, bloody insurgencies. He recognized the parallels, especially after one of his heroes, Secretary of State Colin Powell, a fellow veteran of the Americal, took the fall for the Bush Administration's half-baked intelligence. The spike in casualties, both civilian and military, made him so furious and agitated that he could not longer read the days-old newspapers. At least the VA — which Andrew resented for letting down his generation — seemed better prepared to deal with the thousands returning home with severe PTSD. That is, until suicide rates among returning veterans spiked.

In those awful days of constant American bloodshed, investigators for the Georgia Resource Center, a nonprofit law office that receives state funding to challenge capital murder convictions for indigent inmates, approached Andrew about his case. They found it hard to imagine a decorated veteran with such a well-diagnosed, combat-induced mental illness receiving a death warrant. Despite an overwhelming load of cases, they encouraged him to file a habeas corpus petition.

It was a significant undertaking, so the investigators sought help from Lane Dennard, a longtime partner at the prestigious Atlanta law firm King and Spalding. They targeted Dennard because he had survived combat in Vietnam as a decorated company commander and later built a reputation as an advocate for disabled veterans. The fact that Andrew received a 100 percent disability rating for PTSD — without a lawyer — astonished Dennard. The VA does not just hand those out, he knew all too well, especially to someone who made no effort to abuse the system. Executing a man that mentally ill, let alone a combat veteran, did not square with Dennard's interpretation of good law. He put several of King and Spalding's top trial lawyers on the case.

In August 2006, Butts County Superior Court judge Richard Sutton presided over Andrew's habeas hearing in Jackson. It looked and felt like a new trial, lasting three days and including 49 volumes of exhibits. There was no jury, so the state attorney general's office did not pursue the shameful rhetoric heard at trial. No one slandered Andrew as the devil or questioned the legitimacy of PTSD as a medical diagnosis, but the state stood firm in defending Andrew's conviction and death sentence.

Andrew's new lawyers argued that Richard Taylor, his first trial attorney, did not provide effective council. They put Taylor on the stand, and it soon became apparent that he lacked experience in capital murder defense. As a result, he failed to correctly dramatize the intricacies of Andrew's mental illness and the trauma of his combat tour. During the trial, for example, Taylor did not put Andrew's psychiatrist, Dr. Boyer, on the stand. Nor did he seek out veterans who served with Andrew to testify during sentencing.

Judge Sutton heard a much stronger defense. Andrew's new lawyers produced three hard-won affidavits from soldiers who fought under Andrew's command. One of the soldiers, Thomas Darinsky, served in Andrew's four-man squad. He was walking point when Capt. Shaw stepped on that tripwire. Shrapnel from the bomb tore into Darinsky's head, his back and his leg, putting him on the dustoff that included Shaw's mutilated corpse. Down in Jackson, Darinsky vouched for Andrew's integrity, calling him "a good man, very compassionate, easy to get along with, good rapport with the men."

The mystery of why Andrew snapped that particular day in 1998 remained elusive. Judge Sutton heard one controversial but persuasive argument the original jury did not. The FBI calls it "suicide by cop," or SBC, for the rare instances when individuals try to provoke a violent reaction from police as a means of committing suicide. As Judge Sutton learned from defense expert Dr. Keith Caruso, Andrew probably didn't experience a flashback — he just wanted to die. He was trying to force Deputy Dinkheller into a violent encounter by immediately shoving both hands into his pockets, by dancing erratically in the street, and by rushing multiple times into the deputy's space. As the situation got more serious, he snapped out of the fog and reverted back to his military training. That's why he told the GBI, after his capture, about not wanting to commit suicide like so many others. The idea had clearly been on his mind.

Judge Sutton deliberated for more than a year. In March 2008, he "vacated the death sentence for the purpose of retrial." The reasoning made common sense: Richard Taylor should have convinced Andrew to plead "guilty beyond a reasonable doubt but mentally ill" instead of "not guilty by reason of insanity." That would have forced Andrew to take responsibility for the crime and allowed Taylor to spend his time preparing a case for leniency instead of trying to meet the nearly impossible legal hurdle of proving insanity.

No one really celebrated the reprieve, because the state appealed. A few months later, Esther sat inside the Georgia Supreme Court, its marble facade inscribed with a Latin phrase that translates: "Let justice be done though the heavens fall." She listened as the court rejected Judge Sutton's arguments and eventually overturned his decision with this opinion: "We conclude that, unlike the case of juvenile offenders and mentally retarded persons, there is no consensus discernible in the nation or in Georgia sufficient to show that evolving standards of decency require a constitutional ban, under either the Constitution of the United States or under the Georgia Constitution, on executing all persons with mental illnesses, particularly persons who have shown only the sort of mental health evidence that Brannan has shown." Andrew's conviction and death sentence were reinstated.

Seven long years of federal petitions and final pleas could not spare Andrew's life. His legal team argued the perfect precedent, a 2009 case called Porter v. McCollum. In a unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of Korean War veteran George Porter because his lawyer failed to present enough "mitigating evidence" showing that "his combat service left him a traumatized, changed man." Andrew's lawyers cited that case until the end, exhausting every possible avenue and submitting dozens of petitions for relief. The federal courts — including the U.S. Supreme Court — simply refused to intervene.

Despite the international attention it receives for capital punishment, Jackson, Georgia, is a very small town with a quaint downtown square and nearby access to Interstate 75. Esther grew up there as a child, and dozens of her surviving relatives, the Norsworthy clan, still lived in close proximity when Andrew took up residence on death row. Rather than cower in shame, Esther took courage in her faith and made weekly trips — a 29-mile trek — from Stockbridge to the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification State Prison. She also rallied a battery of family members who had to undergo background checks before making the prison's guest list. Some showed up for those early visits wearing dresses or shorts, only to be told to return when they had covered their legs.

Inside the visiting center, Andrew, ghostly white from the lack of sun, waited politely around a circle of chairs that he'd prearranged, surrounded by guards. The family played simple games and told stories, acted out skits and prayed for mercy. Andrew usually spent those precious hours working his way around the room to thank everyone for coming and took his breaks in the least comfortable chair.

Esther's mind started to fail in 2010. She initially refused to leave home, but the unaccounted for dents to her car and the scary falls around the house made it inevitable. Later, at the age of 94, she suffered a stroke, lost much of her memory, and required assisted living. It fell on Bobby's twins, Crissy and Cathleen, to take over what they called "Uncle Andrew's business." His nieces had grown into successful young women with growing families of their own. Despite tiger-mom schedules and independent careers, they shouldered the burdens of caring for Esther and Andrew, who would call collect nearly every week with another list of good deeds to complete for his fellow inmates. He loaned them money, bought them shoes, and even helped one prisoner put his child through law school. By 2014, Crissy and Cathleen's visits to the prison had become so frequent guards routinely asked for updates about Mrs. Esther.

Crissy's daughter, Beth, never really knew her uncle Andrew until those middle school trips to Jackson. She had been born just a few weeks after Andrew's crime, and it broke her heart to leave him behind on a Sunday afternoon. For a teenage girl blooming into a spirited actress, Uncle Andrew, lonely and bored on death row, became the perfect "besty." She picked up when he called the house with those notorious lists and chatted with him about anything — boys, school or religion. She sometimes put her friends on the phone to say hello. Andrew encouraged her to study hard, to prepare for college. He always tried to sound positive, venting jovially about his most recent buzz-cut, but she could hear the sadness in his tired voice.

In December 2014, just before New Year, the twins received word from Andrew's lawyers that the death warrant had been issued. Everyone took it as a relief, an end to the nightmare. But at the same time, the thought of his death brought back raw emotions from 2004, when their older sister, Cindy, died in a mental hospital after a long bout with depression and alcohol. What had held them together was their Christian faith, so to prepare for Andrew's final week of life, they bought sunglasses in the shape of hearts, amassed Bible verses handed down through several generations, and collected prayers to send with Andrew up to heaven. Esther no longer understood the circumstances of her own life, but in the days before Andrew's death, Crissy walked into her private room and kept Andrew on the phone as she awoke from a nap. The last words he heard his mother say were: "I love you, too."

Beth sobbed for days. She couldn't believe the final mug shot that appeared on the Internet. Andrew looked so sad, so defeated — nothing like the big teddy bear who cared so much about her promising young life.

The Georgia state parole board, an all-male body comprised of political cronies and corrections personnel, picked a symbolic date for the clemency hearing: January 12, 2015, the seventeenth anniversary of the crime. Despite little chance of success, Andrew's lawyers mounted a passionate defense, including testimony from seven veterans. Lane Dennard, who had since retired from King and Spalding, told the board that killing a veteran who'd been treated so poorly by his own government, regardless of the crime, put shame on the Constitution.

With 2015 marking the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, now seemed like the perfect time to stop executing mentally ill combat veterans. Brannan's lawyers argued that national and international trends pointed to the demise of capital punishment, particularly for inmates with severe mental illnesses. In fact, Texas prosecutors were not even pursuing the death penalty against the mentally disturbed soldier who point-blank executed Chris Kyle, better known as the American Sniper. Texas had shown mercy at a time when Clint Eastwood's biopic of the victim remained No. 1 at the box office.

Unmoved, the parole board rejected Andrew's petition in a split decision.

One of the last people to see Andrew alive was Dick Tolcher, a Catholic deacon who received a Bronze Star fighting for the Marines in Vietnam. He'd met Andrew a few weeks earlier at the family's request. On the morning of the execution, he led them all in prayer, as Andrew closed his eyes and pleaded for forgiveness. The twins and their families, including Beth, stayed for six hours, assuring Uncle Andrew that he was not a failure, promising that he would soon meet his father and brothers in the free open spaces of Heaven. Andrew's last supper consisted "of three eggs over easy, hash browns, biscuits and gravy, sausage, pecan waffles with strawberries, milk, apple juice and decaffeinated coffee."

The family left Jackson several hours before the execution. Protestors against the death penalty and television reporters would soon line the entrance to Georgia's death house. Andrew had asked Tolcher to bear witness on the family's behalf, so just after dark, he took a seat in a small room that included Deputy Dinkheller's widow, Angela, and his father, Kirk, as they waited quietly for the closure they'd been promised. The deputy's born and unborn children had grown into young adults without a single memory of their father. In only a few years, they would outlive him.

"Nothing will ever bring my son back," Kirk Dinkheller wrote on Facebook, "but finally some justice for the one who took him from his children and his family."

Laurens County Sheriff's Office personnel and peace officers from across the state hovered over the family as they waited for the U.S. Supreme Court to reject Andrew's final plea. Word came down around 8:30 p.m. Tolcher listened as the warden asked for Andrew's final words. Sedated and strapped to a gurney, the condemned man expressed his "condolences" to the Dinkheller family, before blasting the misery of life on death row. The warden then asked for a final prayer.

"I'm glad to be getting out of this place," Andrew blurted out. "And Dick, you're in charge." Tolcher was still processing the comment at 8:33 p.m., the moment Andrew's heart stopped beating.

As he drove away from the prison that night, Tolcher figured out what Andrew meant. Earlier, he'd promised to check in on Esther, who would never know that she had outlived all three of her sons. That's what Andrew meant by "you're in charge." He was relieving himself of duty.

As the state transported Andrew's body for cremation, television stations and newspapers across the world reported the first U.S. execution of 2015. Some noted that the deceased, a 66-year-old Vietnam combat veteran from Georgia, had issued a final statement through his Atlanta-based attorneys. The words read like the prayer of any true soldier, at any point in our history.

"I am proud to have been able to walk point for my comrades," it ended, "and pray that the same thing does not happen to any of them."

~~~

Pate McMichael is the author of "Klandestine: How a Klan Lawyer and a Checkbook Journalist Helped James Earl Ray Cover Up His Crime" (Chicago Review Press, 2015). Currently, he teaches at Georgia College as a senior lecturer in Mass Communication. For additional photos and material on "The Last Casualty," please visit his website: www.patemcmichael.com