The Bitter Southerner delves frequently into the history of the South, but our explorations reach back no more than three centuries. Today, we dig far deeper — into the South of 90 million years ago, when Appalachia was not a mountain range, but a continent. And we tell you some fantastic stories — speculations, yes, but based on real paleontology — about the beasts that roamed our lost continent.

This is our land, lost deep beneath the veil of history.

It lies under Georgia’s forests and Tennessee's mountains, beneath the coves of North Carolina and compacted layers of Alabama stone, beyond battlefields and farms, beyond mines, beyond roads walked by European settlers and diasporic Africans and the first nations of the Native Americans. Our lives drape over it, but its story is seldom told.

Ninety million years ago, in the high Cretaceous — the last great epoch of the dinosaurs — a combination of sinking plates, volcanic activity and rising waters split the American continent down the middle. The warm Niobraran Sea sea rolled in a 620-mile-wide trough across what is now the Great Plains and lower Southeast. Where once there had been a single continent, now there were two. To the west rose Laramidia, a landscape of proud mountain slopes stretching from southern Mexico to western Alaska; to the east, the continent of Appalachia, covering everything from the Canadian Maritimes to the Alabama fall line. Only at the end of the Cretaceous — about 66 million years ago — did the Niobrara retreat and the continents rejoin.

The remnants of that age still fill our books, movies, and museums: Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, the spike-headed Styracosaurus, club-tailed Ankylosaurus, and raptor Deinonychus, crocodiles, and lizards and tiny mammals, a symphony of fossils weaving together to tell the story of our planet.

Yet our vision of North America in the late Cretaceous is incomplete. Nearly all of our fossils come from the western deposits of Laramidia. From Appalachia, there is largely silence and void. Few professional paleontologists work on its sediments. Even among amateur enthusiasts, its creatures aren’t household names. It is as if half the story of Cretaceous North America is simply...missing.

But Appalachia obscures its prehistory, just as it has hidden peoples and customs in more recent times.

The Mesozoic rocks of the South are largely covered by either thick vegetation or urban sprawl, exposed only at scattered creeksides, road cuts and chalk-pits. The remains at these sites are not immediately impressive: impressions of leaves, pieces of bone, scattered teeth, or, at best, a rare partial skeleton. Bodies from the Appalachian continent come to us only after being broken up and mixed by the action of waves, or after floating out to sea, and the riverine sediments of the interior don’t preserve bones well.

Paleontologists themselves have not been kind to Appalachia, either: After an initial period of interest in the late 19th century, fossil hunters largely abandoned Appalachian deposits, lured by the spectacular fossil riches of the West.

Only recently have they begun to turn their eyes eastward again, drawn by enticing new discoveries in southeastern states. Like explorers at the edge of an impassible coast, they work from intriguing scraps, uncovered from remarkable sites like the chalk deposits of central Alabama or New Jersey’s Ellisdale Fossil Site. But put enough scraps together, and you can catch a glimpse of something more: the shape of a body, the shape of a forest, the shape of a land lost beneath fathomless time.

Appalachia.

What you are about to read is an attempt to take us deeper into the history of the South than most of us ever go, and breathe life into ecosystems and species that no longer exist. What follows is a tour of a single day, 80 million years ago, on the continent of Appalachia. We will dive into killing seas, walk whispering beaches, and watch huge things moving in the dark forest.

In leading you through this world, I’ve relied on current paleontological thinking. But the past is a foreign country. You can never be correct when you speak of it; you can only be wrong by varying degrees. The choice facing anyone who wishes to reconstruct prehistory is whether to be boringly wrong or excitingly, dashingly wrong. This being The Bitter Southerner, we have opted for the latter.

Strap in. Our lost continent has been ignored long enough. It’s time to resurrect it.

Morning on the Alabama sea. Waves lap in under blue skies. Miles out from shore, sunlight drifts in gentle curtains through clear waters, caressing the sides of a high, jagged reef. The waters are too hot for corals; instead, walls of bivalve mollusks sit in scaffolds dozens of feet high, their shell surfaces encrusted with barnacles and long strands of algae. Marches of immense clams gape into the currents. Shoals of fish dart and swirl, chasing tiny shrimp. An octopus-like ammonite creeps from outcrop to outcrop, tentacles probing, stalk eyes bulging, its coiled shell shining in brilliant colors. A muffled chorus of clicks, squeaks, and croaks echoes along the reef.

Diving into these waters as a human would be like slipping into a warm bath. Even this far from the equator, seawater temperatures hover at a year-round average of 90 degrees or higher. Hot oceans lead to low currents and frequently stagnant waters — the lower reaches of the inland sea suffer frequent drops in oxygen, fueling vast dead zones. Fueled by the heat, massive hurricanes sweep along the coasts, churning up the bottom and carrying tracts of organic material out to sea. But the turbulent ocean supports riches, too: The combination of shallow waters, abundant sunlight, and upwelling nutrients feed a variety of monsters.

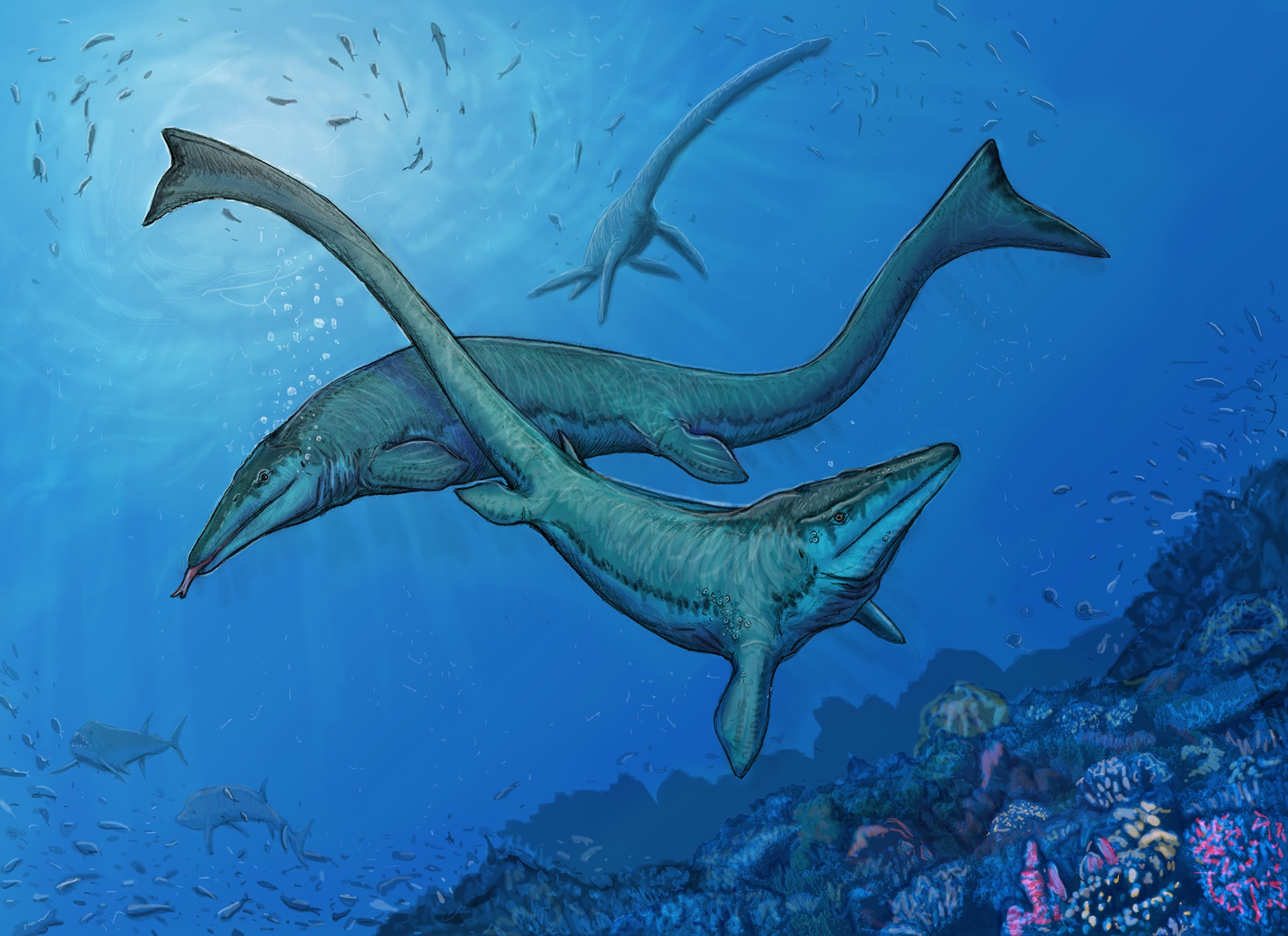

A male and female Tylosaurus perform a mating dance above the mullusk reef. In the gloom to the left, a pair of Xiphactinus hunt fish; above to the right, an Elasmosaurus flies through the water on the same mission.

An immense shadow slides over the mollusk reef. The fish panic, contracting into mirrored walls or exploding into dizzying clouds. With a squirt of sea water, the ammonite pulls inside its shell. Sculling overhead is a 40-foot Tylosaurus, her flippers tucked against her sides, keeled tail moving in slow, sinuous strokes. She’s a mosasaur, a descendent of small monitor lizards that colonized the sea in the earliest Cretaceous. As competing families vanished or turned to specialized fish-eating, the mosasaurs exploded in size and colonized every ocean in the world. The waters of Alabama alone play host to the portly, clam-crushing Globidens, the swift Platecarpus, shy Clidastes, and Tylosaurus, ruler of them all.

This mosasaur is formidable, with long, heavy jaws and a crushing bite. She moves through the water with the lazy assurance of an apex predator. Years ago, she claimed a stretch of the surrounding sea with access to both deep water and high reefs, and now she knows it by heart: the best spots to settle in for a nap, where the cleaner fish gather to nibble at parasites and flakes of dead scales, and most importantly the spots where she can lurk undetected, waiting to seize anything — fish, diving bird, or smaller sea-lizard — outlined against the surface.

Her black eyes scan the riot of colors. Most of the time she guards her territory jealously. But once a year, she makes an exception — for her mate.

He’s coming now: a 46-foot titan, his scarred, barnacle-encrusted head swiveling. A broad tongue laps out, checking her scent trail, trying to assess whether she’s receptive. She circles around, investigating him in turn. She knows him well: Like her distant kin, the modern Komodo dragon, Tylosaurus sometimes form loose but long-lasting relationships, splitting for much of the year before coming together in the breeding season. Despite their familiarity, both are cautious. Mosasaur courtship can swing from tender to violent in a heartbeat, and both bear literal scars from past failed romances. A reintroduction is called for.

Other Mosasaurs of the inland sea: Above, the slender-jawed Clidastes; below, the scarred Platecarpus.

As the fish shift and scatter around them, the two leviathans begin to dance, sliding and spiraling slowly through the water, tongues flicking gently against each other’s sides. Their pebbled flanks brush together, rasping in the water. Once or twice she breaks off when he presses too close, throat inflated in warning, bubbles curling from her open jaws. The male swerves off each time. Then, he returns, and the dance continues. They’ll keep up like this for an hour, breaking occasionally to gulp air, before the male twines around her in a quick embrace. After a few weeks of mating, he’ll be gone; after seven months, she’ll deliver a litter of four tiny pups in open water, a hundred miles from land.

Slowly, the ammonite emerges from its coiled shell and continues its trundling path along the corals. The shoals calm and flit back: The mosasaurs are simply too large to register as a threat for long.

Down among the shells and algae, a flurry of shapes dart along the mollusk reef. These are Enchodus, a three-foot fish with long, projecting teeth and a taste for squid. Theirs is a much more nervous world than that of the Tylosaurus; while beneath the notice of the courting giants, they’re comfortably on the menu for everything else. One of the fish in the shoal has a broken fang and ragged fins, the scars of a run-in with a larger hunter. He turns with the group, scales flashing, eyes staring. The school is his only protection against the terrible, open water on all sides; Together, their silvery scales catch the sunlight, the group shifting and merging in dizzying arrays. More Enchodus shoals rise from the reef and gather into a vast feeding school.

To hungry eyes, such a school is irresistible. A pair of huge bulldog tarpon, Xiphactinus, slip up from the murk, piranha jaws hanging open. The Enchodus bunch closer, wheeling into a tight ball, scales flashing and shimmering in the water. Bulldog tarpon are gluttonous, happy to swallow anything they can and many things they can’t; several fossils preserve them choking to death on ambitious morsels. But the Enchodus are too small for such posthumous revenge, and their projecting fangs are too spindly to protect them. The bulldog tarpon race in, striking at the bait ball and breaking away, attempting to scatter the school. But the flash of light on scales dazzles them, makes it hard to pick a target. A Xiphactinus’ jaws snap shut just above the scarred Enchodus. The shoal turns, panicked, pressing closer into the ball. Something else is emerging from the gloom: a small head with long, interlocking teeth, borne at the end of a long neck and flippers that flap like wings. An Elasmosaurus, one of the great plesiosaurs, has come to join the feast.

Pteranodon is the most famous of the pterosaurs, and its bones are found throughout the rocks of the inland ocean.

The shoal is largely leaderless, but information is transmitted quickly, each fish reacting to the movements of its fellows. A bulldog tarpon dives in from above, and the school dissolves around it, then reforms, only for the Elasmosaurus head to dart in. Panicked clicks drum out across the water. The school is being driven closer and closer to the surface, where they will be trapped between their pursuers and the awful emptiness above the waves. The scarred Enchodus is buffeted by the other fish, sometimes cast to the outside of the school, sometimes safe inside, his vision filled with whirling fins and staring eyes. Occasionally, a predator races in and the shoal presses against the surface, shoving him up into the choking void before the waves reclaim him.

But now the shoal has been noticed from above. Something plummets into the water in a column of white bubbles, beak opening, wings unfurling, seizing a startled Enchodus before paddling back toward the surface. The school wheels. The scarred Enchodus finds himself again on the outer edge. Even as he presses back in, a long, pink beak fills his field of vision, and a crushing weight bites into his sides. He is borne up through the water and into the void and tossed up. He hangs in the air a moment, flopping. The beak snaps and swallows.

The Pteranodon feels the Enchodus slip down his throat, water beading on his slick fur. This one, narrow-hipped and with a long, projecting crest, is a male; he was riding the thermals overhead when he noticed fish jumping and squirming on the waves, a sure sign of an easy meal.

Despite appearances, he is startlingly at home underwater, able to zip around with long strokes of his partially folded wings. His beak snaps out to spear another Enchodus, and then another. He surfaces, swallowing, before considering his options. The bait ball has dwindled somewhat over the past 15 minutes: More predators have arrived to circle from below, including a tusked, swordfish-like Protosphyraena and a couple of raven sharks. These, the Pteranodon eyes with extreme distaste; sharks and bulldog tarpon are greedy eaters, and he’s seen more than a few of his fellows yanked beneath the surf.

On impulse, he cocks his head and ducks beneath the water, just in time to glimpse a raven shark cruising toward him from the blue depths beneath the bait ball. A hot spike of panic spears his breast. His huge wings slam downward into the water, once, twice, the force skipping him across the waves like a stone. One more flex of his powerful shoulders, one more galloping stroke of the wings, and he’s free and clear, flapping up into the warm sky.

The sun is high now, white clouds swirling in heavy arcs, crisp against the eternal blue sky. Squalls gather in distant black lines over the western horizon. The Pteranodon banks, stiff wings flaring, shadow racing over the sparkling waves. The wind is with him; soon, he’s soaring over a lattice of barrier islands and mollusk reefs, black-and-white stripes layered on the cerulean waters, their surfaces thronging with the distant shapes of seabirds.

We can’t follow him where he’s going. Instead, we drop toward the coast, where the movements of rivers, waves, and sand combine to keep a scattered record, and thick forests march down to meet the shining waves.

In the baking light of early afternoon, soft waves slide against the coasts of the continent, sweeping layers of flotsam and driftwood high onto the white sand. Salt winds blow off of a wide, green bay, ruffling the wave caps and battering the rows of shallow dunes, stirring the coarse shrubs into rustling song. Beyond, conifers drop decaying needles and cones in rich carpets on the ground.

Signs of bustling life are everywhere, written out in complex networks of trackways — the delicate impressions of birdlike feet, the vague troughs of turtles coming up from the water, the dipping furrows of crabs and burrowing sandlice. In one spot, huge, three-toed tracks approach the water’s edge and vanish in a confused muddle of sand.

As it still does today, the bounty thrown up by the sea brings together creatures that otherwise seldom mix.

In the early afternoon, a Nodosaur comes down to the shore to scavenge for seafood. Across the inlet lie a pair of massive Deinosuchus. Bold Icthyornis--toothed birds--squabble on the rocks.

As seabirds flit overhead and small pterosaurs clamber amid the nodding pine boughs, a massive crocodilian hauls herself out of the waves and onto the warm sand. She’s a Deinosuchus of the eastern tribe, a 30-foot relative of the alligator with a broad crushing snout and a hide studded with domed armor. Another member of her species is already sprawled out on the beach. She passes it by without a glance, water gleaming on her scales, shells crunching under webbed feet. Deinosuchus are incredibly common along the margins of the Niobrara, colonizing beaches, brackish coves, and rivers with equal enthusiasm. Like modern saltwater crocodiles, they can travel hundreds of miles by navigating ocean currents, occasionally even crossing between the American continents. This female, however, has maintained her hold on this beach for decades, watching generations of animals come and go. Her preferred prey are the big side-necked turtles that inhabit the bay, but she takes bigger game as well. Just this morning she snatched an eastern tyrant, Appalachiosaurus, stashing its shattered remains in a nearby salt marsh. Even now, little fish and crabs have taken up residence inside the shattered body. Where Deinosuchus swims, everything, including predatory dinosaurs, lives on sufferance.

But no predator spends all its time hunting. In fact, like modern alligators, Deinosuchus often spends its day doing as little as possible. She passes much of her life basking or floating, existing in the endless now of crocodile-time, a state of focus that logs the movements of the world yet is rarely touched by them. Only in courtship and nesting does the Deinosuchus display much outward emotion, rushing at interlopers with hissing rage or tenderly guarding her chirruping young. If the other crocodilian sticks around for too long, she will be chased out. For now, the Deinosuchus settles her bulk on the sand a comfortable distance away. Eventually, without any particular rush, she opens her mouth and waits. Soon, groups of bold Icthyornis, toothed seabirds, come winging over to peck scraps of dinosaur meat from between her teeth. Fearsome though she is, Deinosuchus is often generous with her subjects, too. She can afford to be.

At nearly 40 years old, the Deinosuchus is one of the few parts of the bay that has remained constant.

The hurricanes that batter these coastlines in the wet season constantly reshape the beaches and dunes, clearing out vast tracts of foliage and leaving the beachside forests a scattered wasteland of snags and fallen logs. Fast growing pines take advantage of these opportunities, their saplings rapidly taking over any cleared space. Then, the hurricanes come, and the pines sweep back, continuing the dance. The storms are also bonanza for any coastal animals that survive them, casting huge amounts of carrion onto the beaches, and sometimes luring unlikely creatures out of the forest.

A careful distance away from the basking Deinosuchus, a squat nodosaur picks its dainty way over the wet sand, ignoring the cackling seabirds watching from the rock outcrops. Like the rest of his family, he is low-slung and broad-bellied, with a back lined by rows of bone armor and spikes. Despite his bulk, he is fastidious, cropping low-lying ferns, saplings, and flowering plants with quick actions of tongue and beak. Everything goes into his vat of a stomach. Nodosaur guts are fermentation engines, and this, when combined with the species’ sweet tooth, occasionally gets them into trouble. Those who gorge themselves on fallen fruit often end up wobbling about in drunken stupors, charging anything that enters their path.

A shy Clidastes investigates the bobbing carcass of an armored dinosaur.

The storms of the previous evening have cast a few large fish up on the sand. A group of Icthyornis have gathered around a beached sword-eel, tugging off strips of white meat and dancing away before their thieving compatriots can steal them. At the nodosaur’s approach, they take to the air in a rattle of flapping wings and angry protests, dive bombing the intruder. But despite occasionally ducking his armored head, the nodosaur ignores them. It’s not uncommon for herbivores to sample a bit of meat every now and again, and in his wanderings along the coastal estuaries and salt marshes, this male has developed a taste for seafood. He strips the meat from the beached fish with careful, dignified bites. In time, the nitrogen from his beachside excursion will pass with his droppings into the coastal forests, fertilizing the soil, the last step in a chain of energy moving out of the sea.

But energy can flow in both directions: The same hurricanes that cast bounties out of the surf also flood the coastal rivers and marshes, whipping up powerful currents that sweep driftwoods and dinosaurs alike into the ocean. This is what makes the Appalachian coastlines such a valuable window into the period. The record is still spotty, though: Most remains are caught up in the waves, thrown up on the beach and carried back out again, until the tides work them into fragments of bone. Sometimes more does slip though. In the coastal bayous, still waters etch only the impressions of foliage and bark into soft silts, and intense storm surges sometimes preserve animals too delicate to easily fossilize. On rare occasions, a dinosaur carcass makes it out beyond the breakers, where hungry mouths — like that of the sea lizard Clidastes — make short work the meat, leaving whole bones to fossilize in the silt.

A distant rumble of thunder rolls across the bay. The wind picks up, chopping at the waves. Slate grey clouds march against the western horizon. The nodosaur raises his head and, with a worried grunt, retreats up the beach and back into the shade of the pines. Behind him the Deinosuchus lie motionless, birds flitting and squabbling around their massive jaws.

Fifty miles north of the coast, a gentle breeze wafts beneath tangled canopies and over still waters. Sequoia, cypress, and monkey puzzles tower in interlocking trunks over a wide backwater bayou, their branches encrusted with colonies of fern, moss, and creeping fig. Gentle slopes are covered in trees similar to modern beech and walnut, their roots tangled in flowering thickets and piles of decaying leaves. Insects buzz in lazy trails between the flowers. Fruits tumble to the forest floor or plop into the bayou, accompanied by the whoop and honk of toothed birds. Unseen things — striking garfish, perhaps — splash against the surface, sending concentric rings questing out across the reflected forest. The air smells of earth, pollen, and rot, and its humid weight presses down in a suffocating blanket.

This is the temperate Appalachian rainforest, a place known only from scattered leaf impressions, petrified wood and coal, and water-bound bodies. The canopies form a broad, unchanging belt around the continent, with only minimal differences deep into the interior. During the wet season, swollen rivers overflow their banks and spread across the lowlands in a network of backchannels, replenishing ponds and drying swamps. Even the high ground — a relative term here — is cut by narrow, gushing creeks. Plant families that in our day are separated by thousands of miles — jungle ferns and tulip trees, ficus and spruce — grow here in interconnected groves from Montreal to Tuscaloosa. Yet despite the richness of these forests, they seem to support only a few types of large dinosaurs.

To understand why this is the case, it helps to look at the intersection of geology and evolutionary theory. Of the many processes driving the evolution of distinct species, one of the most powerful is geographic diversity and isolation: Animal populations that can’t easily interbreed tend to grow more distinct over time. In Laramidia, the growing Rocky Mountains carve the landscape into isolated provinces, leading to a cornucopia of distinctly horned, armored, duck-billed and carnivorous dinosaurs. But Appalachia’s mountains are dying. By the late Cretaceous, they’ve been reduced to low foothills and slumping tablelands, and it will be many millennia before tectonic processes raise them to their current heights. The ability to move across the entire continent without much effort means that the same sorts of plants and animals are found across the entire landmass. There are only a handful of big herbivores and a solitary big carnivore. The lower ranks of small dinosaurs and birds are doing somewhat better, but can’t match their western comrades in terms of distinct species. The continent is a warning of a coming state of affairs. In 12 million years, dwindling dinosaur diversity will culminate in the catastrophic Cretaceous extinction.

But for now, while biodiversity is low, the creatures that do live here are numerous, successful, and quite distinct from their western neighbors. The continent is a refuge for the archaic and the bizarre, and several million years of isolation have led to ecological relationships that can only be guessed at.

In the shadows of the high boughs, one of the habitat’s primary architects is currently at work, a hundred feet from the bayou’s edge. A duck-billed dinosaur, Lophorhothon, is stripping the nearby vegetation with single-minded thoroughness. Thirty-six feet long and heavy as a bull elephant, she scoops up leaves and ferns, shoulders over saplings, and scrapes orange mushrooms off overturned logs. Everything is mashed by batteries of teeth and swallowed into a bulging crop. She is eating for 10 — several miles away, she and the other females in her loose group have shallow nests filled with crowds of striped, peeping young. For the first month of their life, the chicks are dependent on their parents for food. So, while the males guard against predators, the females spread out on foraging missions.

Appalachia is the ancestral home of the hadrosauroids, the group of herbivorous dinosaurs to which Lophorhothon belongs, and the eastern branch of the family has largely kept the appearance of its forebearers. Unlike their western kin, they generally don’t have elaborate head crests.

They make up for it by being loud.

While forest hadrosauroids generally live in small groups — it’s rare to see more than six adults at a time — their movements through the forest are often accompanied by a racket of honks and rumbles, loose skin on their nostrils ballooning outward in brilliant flashes of color. These groups sculpt the forest in important ways. Several types of plant depend on foraging hadrosauroids to help them disperse, their seeds hitching rides in the animal’s gut and dung. Rooting hadrosauroids break up the rotting logs that otherwise litter the forest floor and wear great muddy wallows in low swamps, deepening the channels. They are also some of the only locals big enough to easily clear pathways through the thick forest, and animals of all sizes use these “hadrosaur roads” to move across their territories.

Hypsibema is one of the largest known hadrosaurs from Appalachia, and likely one of the loudest.

For hadrosauroids like the small, timid Claosaurus of the deep woods, these are the limit of their activities. But the 50-foot behemoth Hypsibema bulldozes through the world, knocking over grown trees to get at fresh growth and waging bruising battles in communal breeding grounds, leaving fresh clearings of trampled earth. Lophorhothon tend to split the difference: For all the logs they overturn and saplings they strip, they generally leave adult trees alone.

But levels of destruction are subjective. For tiny forest-dwellers in the Lophorhothon’s path, the grazing dinosaur is akin to a natural disaster. As she crashes down toward the margins of the water, she raises clouds of disturbed insects and sends smaller animals scurrying. Tiny fig wasps — early members of an evolutionary partnership that will continue for over 70 million years — crawl impotently over the Lophorhothon’s hide as she shakes their vines. On the forest floor, a fat, vole-shaped mammal waddles away from a crushed log at speed, squeaking in distress. Attendant ornithomimosaurs — ostrich-shaped dinosaurs closely related to birds — stalk officiously at the Lophorhothon’s footsteps, heads turning in sardonic arcs, occasionally snapping up small game flushed by the huge feet. While she’ll drive them off if they try and follow her back to the nest site, right now their sharp senses make them useful animals to have around.

The rainforest is not safe in the dusk.

The hadrosaur road ends in a bayou about ninety feet across, slow waters flowing over a deeper channel that is slowly silting over. Liquid mud and layers of decaying leaves carpet the water margin beneath stands of dawn redwood and cypress, their trunks shining dimly in the fading light.

The Lophorhothon and the ornithomimosaur flock emerge onto the muddy bank and hang back from the water for a few minutes, peering around carefully, searching for anything that might betray a lurking crocodilian. Only once the ornithomimosaurs splash out into the water does the Lophorhothon lower her head and begin to drink. Around them, the bayou’s evening shift begins to emerge. Painted frogs and early spadefoot toads hop from beneath rotting trees, croaking a discordant chorus in advance of the evening rains. Side-necked turtles peep up through the mirrored waters, take a breath, and vanish.

Across the waterway, another ornithomimosaur has emerged from the forest. He moves in miserable, jerky strides, stopping every few steps to twist his head back and root through his shaggy coat. At the base of his feathers, tiny bodies scuttle away from the nipping beak.

Ticks, nematodes, and leeches are constant issues for forest dinosaurs, and few are completely free of parasites. But feathered dinosaurs — like their modern avian relatives — are also afflicted by specialized lice and mites, many of which have been evolving alongside them for millions of years, splitting into new species alongside their hosts. To try and cope, most feathered dinosaurs spend a hefty chunk of the day preening.

A pair of Appalachiosaurus scrap over territory. There’s been debate in paleontological circles over whether these primitive tyrants had three fingers or two.

This male’s lice infestation is particularly bad. He slips down the cypress knees with careful steps and squats in the mud, splashing silt and water over his back with long strokes of his plumed wings. Cool relief seeps across his inflamed skin. Yet this is a risky solution: While the mud smothers the parasites, it also fouls his feathers and weighs him down, a potentially lethal tradeoff for an animal that relies on speed.

The bath has also left him distracted at a very dangerous time.

Overhead, clouds march in steady grey strides against the painted sky. The sun has disappeared beneath the western canopy. Deep shadows swallow the tree trunks. Slow, fat raindrops patter on the bayou. He stands, fluffing his sodden feathers, preening out a few of the larger clumps of mud before proceeding back up the bank. A few steps later, he freezes. Something is lurking in the trees.

Instinct tells him to stay still and trust his colors to keep him hidden. But he’s exposed here on the bank, without any clear avenue of escape. Here the trees and shrubs grow thick, and running in the soft mud could break his leg. Across the channel is the hadrosaur road, but to get there he’ll have to plunge into the water, and that will leave his back exposed to the forest. He flinches, stops, and moves in another direction, torn by indecision and fear. As he raises a leg, the unseen hunter makes its move.

Branches snap. The Appalachiosaurus explodes out of the forest in eerie silence, a black streak propelled by long hind limbs, heavy head darting forward like a striking hawk. Time slows; the ornithomimosaur leaps; his massive feathered body blurs past with the force of a runaway train, crashing into the water and floundering, taloned feet slipping in the shallows. A moment later the ornithomimosaur’s feet slam back into the mud. The world tilts, something twanging in his long leg. Behind him, the Appalachiosaurus is turning, tail lashing the surface of the water, a frustrated hiss bellowing from huge lungs. A blast of adrenaline floods his veins and he hauls forward, pain searing up from the ankle joint. In three steps he’s among the trunks and making for the safety of the thickets, the twigs tearing at his sides.

Then a larger form — another Appalachiosaurus — rears out of the gloom, and its jaws plummet from above in a blast of rotting breath. The ornithomimosaur jukes away, the pain in his ankle blooming into grinding agony. Without a sprained leg and mud-clogged feathers, he’d have left a foot of space between himself and the new attacker. Instead, the snapping mouth clamps on a clump of louse-infested feathers. For an instant he’s held fast in mid-air. Then, with a rip, the feathers yank free of his skin and he’s away, hobbling into the dark. With an injured leg, he has a hard future ahead. But for now — miraculously — he’s alive.

Behind him, the two Appalachiosaurus stand on the narrow bank. They are primitive tyrannosaurs, with longer forelimbs and bigger hands than their western cousins, their hides covered in thick, feathered pelts. Both are under 5 years old. But tyrants grow fast: The hunter who made the first strike is 20 feet long and weighs a ton. The other is 25 feet, his jaws webbed by lines of scar tissue, his body by compact, deadly muscle.

Despite appearances, this was not a cooperative hunt: It was a foiled attempt at poaching. Tyrants are rare in these forests, requiring huge amounts of land to sustain them, and males in particular are jealous landlords. The smaller Appalachiosaurus is a trespasser, unable to hold his own territory, and the larger male has been following the offending odor since he noticed it earlier in the day. Now that the ornithomimid is gone, the full force of his attention falls on the other animal.

Normally, the smaller Appalachiosaurus would flee. But by bad luck he’s found himself in the same position as his earlier prey: his back to the channel and a lethal predator blocking his escape route into the forest.

Nothing left now but bravado. He rears, clapping his jaws and fluffing out his feathers in a threatening display. The landlord stands straighter as well, his own feathers bristling, tail arched in a taut bow. They stand there, frozen, water dripping from scaly lips. Huge eyes blink away moisture, watching for a telltale twitch in the other animal. Muscles tense and relax in involuntary ripples. The rain is intensifying, hammering down cold and hard; visibility is dropping by the second.

The trespasser’s nerve breaks. Turning, he crashes back into the bayou, thigh muscles straining to propel him through the liquid, clutching muck. Instantly the landlord is after him, nipping at his sides. Goaded by pain the trespasser wheels and lunges, waves crashing around his thighs. He lands a kick, scoring against the landlord’s flank.

But he should have kept running. What began as a territorial spat is escalating wildly, panic and adrenaline driving both animals into a frenzy. The landlord’s bulk slams down against the trespasser, forcing him under the black waters. Disoriented, he fights his way to the surface, slime arching from matted feathers, only for a heavy kick to hit him in the side, driving a grunt of air from his lungs. The bayou bottom offers little purchase to either, but the landlord’s superior weight and reach are more than enough to make up the difference. The tyrants lunge and snap, bodies slamming together in thunderclaps of displaced water, feet kicking out with terrible force. Again, the smaller tyrant is shoved beneath the surface. His lungs scream; bubbles pour from his mouth. This time when he comes up, the landlord’s jaws close between his shoulder and neck with a crunch of bone. He goes limp.

The landlord wades back onto the bank, coat matted with silt and blood. A lucky kick by the smaller animal cracked his rib. But the trespasser fared far worse. After a few moments, the smaller Appalachiosaurus stirs feebly in the water. The landlord gives a snarling hiss, tail stiffening in threat, but the trespasser is in no shape to fight. Drunkenly he hauls himself onto the opposite bank, the side of his chest a mangled ruin, his breath coming in bubbling wheezes. He limps off, following the hadrosaur road. In a few hours, a combination of shock and the increasingly heavy storm will divert him onto the shores of a flooding river. He’ll drown attempting to cross.

Only a third of Appalachiosaurus make it past five years: A vanishingly small amount reach their full size. But this one is lucky, in a way. The powerful current will carry his body, tangling and bumping it along the log-strewn bottom, before bloat brings it back to the surface. Then, like other dinosaurs before him, he’ll travel back down the line, past the lush wall of trees, past the sandbars and salt-marshes and out into the open ocean, where the silent raven sharks and sea-lizards circle, and the endless tides wait to cover what remains.

These are only a few of the stories Appalachia has to tell. More still wait to be pulled from the stone, or reconstructed from scattered pieces.

In 2015, paleontologist Nick Longrich published a description of a small horned dinosaur known only from a piece of North Carolina jawbone, the first such member of that family known from Appalachia. At the Arlington Archosaur Site outside of Dallas, researcher Christopher Noto has found fossils of other previously unknown animals from the shoreline of Appalachian Texas, although in deposits earlier than those of Alabama. Among the remains are parrot-beaked oviraptorosaurs, Velociraptor-like dromaeosaurids, and members of the tyrant lineage that gave rise to Appalachiosaurus. Work continues on the Ellisdale site in New Jersey, where pieces of tiny Appalachian vertebrates are pulled from the marl pits. Just this year, Greg Erickson and other paleontologists published a description of the skull of a new, primitive hadrosaur, Eotrachodon. Much remains to be done, but after nearly a century of neglect, the study of Cretaceous Appalachia has come into its own.

And yet despite this work, Appalachia itself remains remote, separated from us by the abyss of time. No matter how much we learn, we can never reach it, never fully understand it. It lies beyond all of our works, an undiscovered country, impossible to visit outside dream and imagination, receding with every passing year.

If it has lessons to teach us beyond the simple thrill of discovery, they lie in our attempts to understand what has happened to our planet before, and what might happen again. We are emerging from the chill of the last Ice Age at terrible, unprecedented speed, into a world of rising waters, fiercer storms, falling biodiversity and landscapes bound by cities, roads, farms, and mines. The oceans are gnawing high on the beaches of the Gulf Coast, and may well push higher still. Balances are tilting, ecosystems changing: Something hotter and stranger awaits, and in its wake passes the era we knew. The world that’s coming may not look much like that of the Late Cretaceous, but there’s a terrible possibility it will end the same way. Time passes, and its crushing weight erases nearly everything. Ultimately, we all live on lost continents.