A Thanksgiving Story

Story by Chuck Reece | Photos by John-Robert Ward II

My father, Clarence Reece, and my mother, Flora Smith, got married in February of 1940 while sitting in the cab of a Dodge pickup truck.

Dad was 20 years old, and Mom had just turned 18. The way I heard the story, they just decided one day to get married and drove up a dirt road in a driving rainstorm to the house where preacher Otto Brawner lived. Otto waded through the mud to the truck, and they asked him to marry them on the spot. So Otto leaned in through the driver’s side window and conducted the ceremony.

He got soaked, but whatever Mom was wearing for a wedding dress stayed pretty. He was a good man, Otto Brawner.

Clarence and Flora must have figured there wasn’t much point in staging a more formal wedding. Dad was the 11th of 12 children born to Richard and Rosley Reece, and Mom was the youngest of four kids belonging to Belle and Burdine (just plain “Burd,” even to his grandkids) Smith. Weddings had probably long since lost their appeal in the Reece and Smith households. In the Reece home, my grandparents had even given up on middle names. After eight boys, they gave my father one name only: Clarence.

Mom and Dad tried for many years to get pregnant, and finally, Charles B. Watkins, the Ellijay town doctor, had declared Mom could never have children. Then, in the spring of 1960, not long after my parents’ 20th wedding anniversary, Mom began to show the telltale signs. Dad caught Doc Watkins on the street as he was returning from lunch.

“Doc,” Dad said, “I think Floss is pregnant.” Floss was my mom’s nickname.

“The hell you say,” Doc Watkins replied.

Almost nine months later, on Jan. 10, 1961, Flora Louise Smith Reece gave birth to her only son, me, a month and two days before her 39th birthday.

I guess you could say I was a miracle baby.

Clarence and Flora Reece, 1940

~ The Gospel Quartet ~

How would a young couple in the Appalachian foothills in the 1940s and ’50s spend their time if they had no children? Surely, they felt left out as their 14 brothers and sisters birthed countless cousins into the family. So Clarence and Flora did something different for themselves.

They put together a gospel quartet. It was the 1940s teetotaling Appalachian Baptist equivalent of starting a rock band.

My mom sang alto, and my dad sang bass. One of my uncles, Roy Kiker, sang lead, and their friend G.L. Moore from down in Jasper handled the tenor. Another friend, Eva Simmons, played piano. The five of them spent years traveling from church to church in the mountains of Georgia, Tennessee and North Carolina, singing for whatever the congregants would deposit in the “love offering” plate at the end of the service.

They never even got close to fame. It didn’t help that they never really named their group. They were called The Gospel Quartet. It was like naming a funk band The Funk Band.

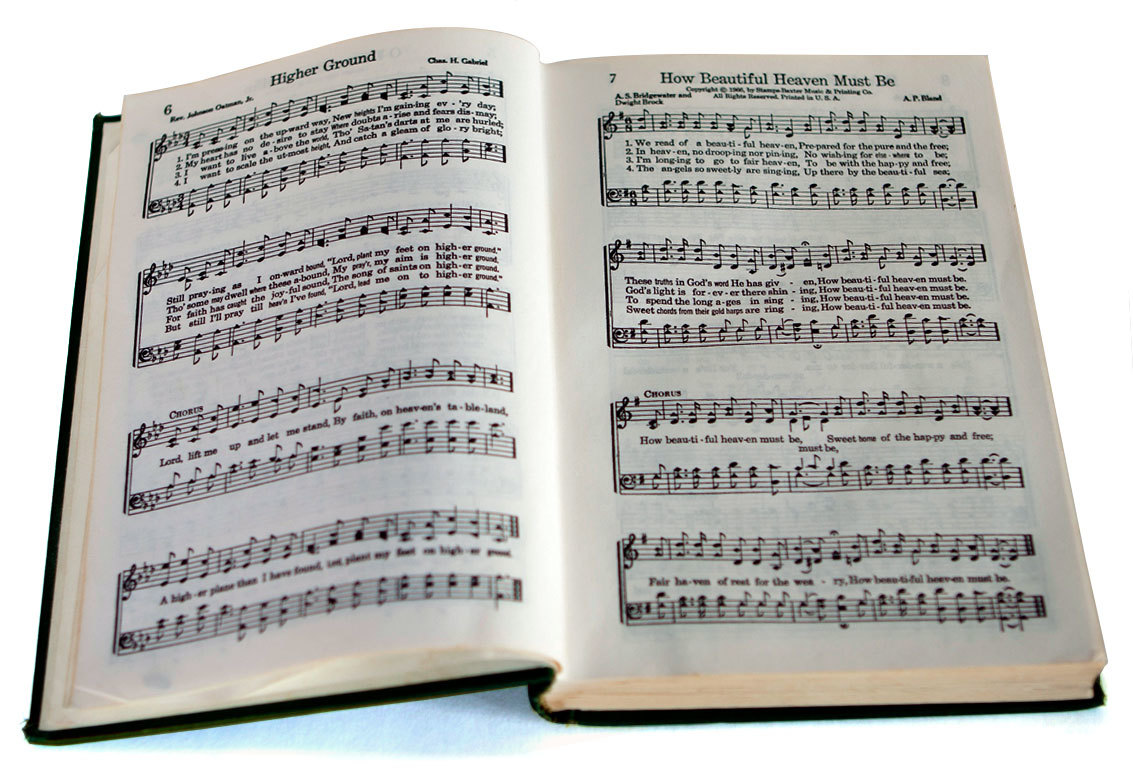

What they sang was firmly in the tradition of Southern gospel quartet music that flourished across the South in the middle 20th century.

Well, really, there were two traditions, because Jim Crow wanted it that way. In the late 1940s, gospel music — particularly in the four-part harmony quartet style — began to break out of the South’s churches and into auditoriums. It became not only a form of worship, but also a form of entertainment. This phenomenon happened simultaneously in the black and white communities of the South.

Black people had Rev. Claude Jeter and the Swan Silvertones, the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Golden Gate Quartet, among others. White folks had Hovie Lister and the Statesmen, the Blackwood Brothers Quartet and the Speer Family, to name a few.

The black quartets gave themselves a bit more room for the inspiring improvisation and swing that was typical of black church music. But a few of the white quartets could give them a run for their money if they locked into the right groove on the right song. I’ll put the Statesmen’s version of “Get Away Jordan” right up there with a Swan Silvertones classic like “Oh Mary Don’t You Weep.”

Jim Crow laws prevented the black and white quartets from sharing venues. Dad and Mom brought me to many of the “Wally Fowler All-Night Singings” at the old Atlanta Municipal Auditorium, and I don’t remember ever seeing a black quartet sing.

But the songs themselves crossed the color line. As I grew up, we watched the Civil Rights Movement unfold on our black-and-white TV, and I noticed that Dad began taking great care to point out that many of the songs we loved were the work of black songwriters. When a white quartet would do “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” Dad would tell me about the great Thomas Dorsey. Or when someone would sing “Just a Little Talk With Jesus,” Dad would tell me a little history about Cleavant Derricks, the black Chattanooga minister who penned countless gospel standards.

It was his indirect way of telling me he believed we were all equal, at least in God’s eyes.

By the time Dad began schooling me in the history of gospel music, it was already two decades after Mom and Dad had started a band, as it were. The Gospel Quartet came together after Dad got home from World War II. Drafted in 1943, he’d served as a private in Gen. George Patton’s Third Army in Europe. He came home in one piece in 1945 with a Silver Star medal and a tattered picture of my mom bearing the message, in her neat handwriting, “Lots of love, Flora.” It had survived the Battle of the Bulge in his wallet.

The late 1940s and early 1950s were the heyday of my mom and dad’s singing career. But in 1957, they quit their weekend tours of mountain churches and settled in to life in Ellijay. Four years later, I came along, and I became the center of their attention. But even though their quartet was gone, music remained at the core of their existence.

They kept singing because they loved it, and I grew up loving the sound of Mama’s country alto soaring above Dad’s deep bass. Dad was the choir director at Pleasant Valley Baptist, our little country church, and mom became the de facto leader of the alto section. I grew up in the back row of the choir, bathed in music.

To this day, I can't recall a single fight between them. Even years after the quartet had parted ways, the two of them on certain nights would spontaneously break into "I Can Call Jesus Anytime" or "Love Lifted Me" at the dinner table. Their love for each other was as harmonious as their voices. The hymns connected them.

By the time I entered elementary school, I understood that my dad and I shared our two greatest loves: music and Mama.

~ The Source of Tolerance ~

Dad was never very forthcoming about the war. He was a gregarious storyteller, but until he was deep into his 70s, he shied away from that subject. When I was 12, I was alone at home after school one day and went digging through an old cedar chest that sat at the foot of my parents’ bed. They’d always made clear the chest was off limits to my prowling, but that day, I opened it anyway. In the chest I discovered a blue leather box with the words “Silver Star Medal” embossed in gold on the front. In it were the medal and a folded sheet of parchment. It was the citation, the document that explained why my dad was given this decoration.

The citation told the story of how Pvt. Clarence Reece, out on a reconnaissance mission with a replacement soldier who’d recently joined his company, had encountered a German tank in the village of Werkel and had been spotted. My dad sent the replacement back to the company for reinforcements. When the tank’s commander rose from the turret, Dad shot and killed him. The German’s body lodged in the turret. The Nazis inside the tank could not dislodge it and thus could not move the vehicle. Dad ran toward the tank and got close to it, underneath the reach of its big gun barrel. He exchanged fire with the Nazis and held the tank until his company reached him.

The short version: Clarence Reece singlehandedly captured a German tank.

At the time I went prowling in the forbidden cedar chest, I had developed a fascination with military memorabilia. A lot of us kids wore Army jackets to school, and every time my friends and I got the chance to go to an Army surplus store, we’d hunt for different insignia to sew or pin onto our jackets, with the goal of outranking each other. So when I discovered that my dad was a legitimate, certified War Hero, it was a big deal.

Dad came home that afternoon, and I showed him the blue box.

“Why’d you never tell me about this?” I asked, eager to hear his version of the story.

“Because I had to a kill a man to get it,” he said. He took the box from my hand and closed it, then opened the cedar chest and returned it to its place. He said nothing else.

My Dad never came right out and said this directly, but I believe the source of the racial tolerance he showed years later, with his drive to make sure that I gave black songwriters their due, was what he’d seen in the war.

His unit had been among those that liberated Buchenwald, the Nazi concentration camp where more than 50,000 Jews went to their deaths. He never told me about Buchenwald until he was very old, but when he did, I knew the experience had changed him fundamentally.

A particular memory of Buchenwald haunted him. Upon arriving at the death camp, his company began breaking the locks on the two-story wooden barracks that housed the prisoners. The imprisoned began streaming outside. Then Dad’s company went upstairs, expecting to find more prisoners. Instead, they found hundreds of cases of canned food.

He and his fellow soldiers had found the imprisoned Jews starving to death, when directly above their heads sat the food they needed to survive. Dad told me he tossed cases of canned vegetables out the window to the prisoners in the yard, then watched them use rocks to beat open the cans, so desperate were they to sate their hunger.

Six decades later, when my Dad was 80 and I was living in New York City, I got a call one day from my cousin Curtis.

“Your old man got in a fight in the barber shop today,” he said.

I was flummoxed. Dad was not a fighter. I think he’d had his fill during the war.

“He what?” I said. “What did he get in a fight about?”

“I don’t know,” Curtis said. “But they said he threw somebody against the wall. I haven’t talked to him. You better call him.”

So I did. Dad answered the phone and I said, “Curtis told me you got in a fight at the barber shop today. What happened? You don’t get in fights.”

“Some little son of a bitch came in and started talking about how the Holocaust never happened,” he said. “Pissed me off. I grabbed him and I said, ‘By God, it did happen. I was there. I saw it.’”

I’m not sure what the young moron believed would happen when he came into the barber shop and started spouting his white-supremacist bullshit. But I’m sure the last thing he expected was for an 80-year-old to come down out of the barber’s chair, grab him by the shirt collar and throw him up against the wall.

Clarence Reece's Silver Star.

~ Big as a Grapefruit ~

As I approached puberty, I still loved the music that Dad and Mom loved, but my interests had broadened. I’d always watched football, and as soon as I was old enough I started playing pee-wee ball for the East Ellijay Elementary Eagles.

Every day, my mom would pick me up from football practice. Sometimes, we’d go to dad’s office, where he sold insurance for Georgia Farm Bureau Mutual, but usually the first stop was Starnes’ Rexall Drugs on the Ellijay town square. She’d buy me a snack, usually one hot dog and a Sprite, at the soda fountain. It was our routine, our daily time to hang out and talk.

And this was a critical time for talking. The truth is, I was never cut out for playing football. I was certainly cut out to watch it, talk about it and write about it. But not playing it. Hell on Earth? Football practice.

I’d talk to Mom about what had happened at practice, which was never much fun. I’d also tell her about how I was afraid to quit because I didn’t want to be left out. In those days, if you didn’t play sports it was hard to be cool. She never told me to quit, and she never told me to keep at it. She just told me that whatever I did, everything would be all right.

Talking to Mama got my head straight. She never sugarcoated things. Flora Reece held no quarter for bullshit. She was plainspoken to everyone. “Floss’ll tell you straight,” I heard it said more than once. And she was funny. She loved to tell jokes. Clean, corny jokes. One-liners. Her delivery was spot-on. Everybody in town loved her.

One day in the fall of 1971, Mama came to pick up me up as usual after football practice. She was 49, and I was 10. But on this day, there was no humor in her eyes.

“I have to go into the hospital,” she told me. “I have to have surgery. They’ve found something in there they have to take care of.”

We didn’t go to the drug store. We went straight home.

A few days later, she was in the hospital — a place in Chattanooga called Campbell’s Clinic. I sat with my dad and my Aunt Elsie, Dad’s only younger sibling, while my mom was in surgery. Her surgeon was a kindly but gruff Cuban immigrant, Dr. E.J. Fernandez. He stuck his head in the door, still in his scrubs, and asked my dad to come out into the hallway. Aunt Elsie told me to stay inside. But I was already close enough to the door to eavesdrop. I strained to hear their conversation. I picked up only one thing the doctor said to my dad.

“It was already as big as a grapefruit, Clarence.”

That was in late October, and Mom stayed in the hospital for about six weeks. We made it home for Christmas. It was the first time I had experienced anything but wild joy on Christmas Day. I remember feeling a darkness in the house. Something foreboding was there, but no one would acknowledge it or talk about it.

A few weeks later, right after my 11th birthday, Mom went back into the hospital in Chattanooga. A month later, we celebrated Mom’s birthday in her hospital room. I gave her a huge, gold-tinted glass vase, a place for all the flowers people were sending. A few days after that, my dad asked me to go for a walk with him on McCallie Avenue, outside Campbell’s Clinic. He told me Mom had ovarian cancer and that she was going to die soon.

She got to come home one more time late in February. I remember the last time we all went to church together. I remember Mom’s alto as the choir sang “Higher Ground.”

Lord, lift me up and let me stand

By faith on heaven’s tableland

A higher plane than I have found

Lord, plant my feet on higher ground.

On the morning of March 13, 1972, back in Chattanooga, I went into my Mom’s hospital room. I took her hand, and it was as cold as ice. It shocked me. She was down to about 90 pounds, but she seemed determined to keep her sense of humor.

“How you feeling, Mama?” I asked.

“With my fingers, like always,” she replied, and managed a laugh.

A couple hours later, Flora Louise Smith Reece died. She was 50 years old. She had been married for 32 years and had been a mother for 11.

~ Growing Up ~

Mom’s death meant instant adulthood for me. Dad was broken. During the six months Mom spent in and out of the hospital, he had been a rock for me. But when she actually passed, he had nothing left. The natural harmony in our house gradually began to dissipate. Part of this surely came from the normal tension that develops between parent and child when child hits puberty. But without Mom in the house, every tension felt magnified.

Although I still went to church with Dad most Sundays, by the time I reached my mid-teens, rock and roll records had replaced the gospel quartet albums in my collection. Life didn’t make much sense to me anymore, so I gravitated toward tunes that reflected the chaos in my head. After I got my driver’s license, Dad rarely objected to letting me head to Atlanta for rock shows with my friends. Then I left Ellijay and moved to Athens for college. A year after I graduated from the University of Georgia, I found myself living alone in a one-room, fifth-floor-walkup apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I was a working journalist, writing for Adweek magazine.

My father was proud of me, but the rest of my family back in Ellijay didn’t much get it. To most of them, the idea of moving even to Atlanta was a frightening thought. But New York? What was wrong with that boy?

In my earliest days in Manhattan, I found myself missing Southern cooking. I’d call Aunt Elsie, who had served as my surrogate mother in the years after my mom’s passing, with questions. “How do you make biscuits? How do you make fried chicken? You remember those apple pies Mama used to make? How did she do those?” Aunt Elsie tried her best to teach me to cook over the phone. Biscuits and fried chicken might be the most basic of Southern comfort foods, but mastering them is no easy feat.

Over the years, I thought of my mother less frequently. Memories faded, as they do, but a few stayed solid in my head. All the sights and sounds and smells of my mother’s kitchen were still as plain as day to me. I could close my eyes and see her hands in a wooden bowl of buttermilk, flour and shortening, gently working them into biscuit dough. I could hear the sizzle of her chicken hitting the hot bacon grease.

But on my little kitchenette stove, nothing came out right. The biscuits were flat and hard. The chicken burned on the outside but stayed bloody and inedible near the bone. One night in Manhattan, with one more batch of bad biscuits getting cold on the counter of my tiny kitchen, I tried to conjure my Mama’s voice in my head. I hoped I could hear her voice as I envisioned her hands in the biscuit bowl and that maybe, as a result, I could turn out something worthy of butter and jelly.

No recipe came. In fact, nothing came. It wasn’t just that I couldn’t imagine Mom telling me how to make a decent biscuit: I could no longer hear her voice at all. I frantically pictured her standing up in church. I let my brain run through every gospel song I knew that had an alto lead. But for the life of me, I could not muster the sound of Mama’s alto, the sound that had been my greatest comfort.

I couldn’t hear it anymore. I had lost my mother’s voice.

~ The Box in the Closet ~

I’ve spent my entire adult life in one of two cities: Atlanta and New York. Atlanta to New York in 1984. Back to Atlanta in 1989. Then back to New York in 2000.

The next year was a bad one in New York, as you might remember. My ex-wife, Allyson Bowers, saw both towers fall on Sept. 11 with her own eyes. I watched them fall on TV in a conference room three miles north in midtown Manhattan, then spent three hours with my co-worker and fellow expat Southerner Allen Putman and his boyfriend Jeff Patrick, walking home to Greenwich Village. We tried to follow the advice we’d heard from cops about avoiding landmarks. We walked west and ran into Rockefeller Center. We turned south and saw the Chrysler Building, so we weaved our way south and west until we got down to 40th Street, which we followed toward the Hudson River. The west side of the island. Our side. Even that route took us just two blocks south of Times Square.

Those cops were nuts, I thought. In Manhattan, you can’t get there from here without passing a landmark. We just kept walking and made it home as fast as we could.

When the telephone connections became solid again, I spoke with my dad quite often. He was 81 then. I’d just call him with updates: how it felt to wake up on Sept. 12 to the frightening sound of complete silence, because we lived south of 14th Street, where nothing but emergency vehicles were allowed to move; how the indescribably horrible scent of flaming everything, the whole world on fire, filled my nostrils. He’d tell me that my stories reminded him of things he’d seen and lived through in France, Germany and Belgium a half-century before.

Not long after, my Dad called to tell me he’d been cleaning out the closet of his bedroom and had found something I might be interested in. A small flat box, less than an inch in height and about seven inches square. On the cover was written, “Gospel Quartet. May 6, 1957.”

“We recorded it one night in the living room with that old Sears reel-to-reel,” he said.

“Just one microphone?” I asked.

“Yeah, just the one that came with the tape recorder,” he said. “I got a buddy who’s a sound engineer. He says he thinks he can clean it up some and make us some CDs.”

A couple weeks later, a package from my dad arrived in New York. Inside was a garden-variety CD-ROM and a handwritten note with a song list — 12 in all.

The first track on the album, if you could call it that, was the voice of my Dad from four years before I was born, introducing the members of the quartet and announcing, to whomever would someday listen, that this was their final recording session.

“We hope,” he says into the microphone, “that in the years to come, we’ll be able to come back and enjoy some of the songs that we have sung over a period of years.” He sounded official, as if he were making a documentary recording for the Library of Congress.

From there, I skipped immediately to “Peace Like a River.” It was an old Blackwood Brothers song, and I knew that my mom would take the alto lead that James Blackwood had sung as a tenor in his all-male quartet. I also knew I’d hear my dad bring in the chorus with a bass lead.

I hit play.

“Peace like a river flows to my soul,” I heard my mama sing. “I’ve been forgiven … cleansed and made whole.”

There it was again. The way my mama let her twang flow even freer when she sang. “Peace like a ree-uh-ver.” The two-syllable word stretched into a comfortable Southern three. Then Mom’s voice, oohing in harmony with Roy’s and G.L.’s as Dad hit the bass: “Peace like a river so gently is flowing. How sweet to my soul is this marvelous peace. Sweeter and sweeter each day it is growing.”

Sweet peace. That’s what I felt. How could I have forgotten that voice? The voice that sang me to sleep at night, the one that made everything broken come back together again, without fail.

~ The Circle ~

On that day in 1972, we had to wait a while for the funeral home men from Ellijay to make it over Chatsworth Mountain to come pick up Mama’s body. It was raining, and I stared out the window of the hospital to look for the arrival of the hearse.

I kept hearing an old gospel song in my head.

I was standing by my window

One cold and cloudy day

Then I saw that hearse come rolling

For to carry my mother away

Will the circle be unbroken, by and by, lord, by and by?

There’s a better home awaiting, in the sky, lord, in the sky.

I'd grown up hearing that song but never thinking much, if at all, about what motivated the writer. Now I wasn't just listening to it. I was in it. I felt, even then at 11 years old, as if I could have written it. That feeling stayed with me for 30 more years, until my dad found that box in the closet.

We’d each had our trials in the years since she passed. It took Dad two marriages after Mom died before he finally found someone he could spend a little happy time with again. As for me, I’d racked up some fat therapy bills and my fair share of mistakes while trying to make peace with the hole Mom’s death had left in me.

My dad got sick in 2002, and we moved back to Georgia so I could help take care of him. I’ll never forget picking him up for a chemotherapy appointment on the morning after we invaded Iraq. As he maneuvered slowly into my Mini Cooper, I asked him what he thought about the invasion. “Makes about as much sense as if FDR had sent me to Mexico,” he said. Both he and Mom always knew how to tell a joke or make a point or both, as the occasion dictated.

I always swore you couldn’t kill Clarence Reece. He’d survived the Battle of the Bulge, bypass surgery, a dead pine that fell on him and crushed his leg, and even a bus wreck when he was on tour with the Apple City Boys, a quartet he sang bass with for a while when he was in his 70s. But multiple myeloma finally got him in 2003. The headline on the front page of the Ellijay Times-Courier, where my time as a writer had begun, said: “World War II hero, gospel singer Reece dead at 83.” There was a picture of him with a songbook in his hand, leading the choir.

But on that autumn day in 2001 when the lost voice arrived in the mail, I called him and we just enjoyed talking. We both felt happy. We felt contented with each other. Neither of us said so, but I think we were remembering who we had been before, all those years ago. The music, the harmony, had done its trick. Mama’s voice had made everything broken come back together again, as it always had.

Two blocks from my apartment building, the trucks on the West Side Highway were still hauling away wreckage, but my adopted city was beginning to come back. Things were starting to feel sort of normal again. Hearing Mom’s voice had made me feel hopeful for the first time in a while. Thanksgiving was approaching, and we both had something unexpected and precious to be thankful for that year.

“Sure sounds good to hear her again, don’t it?” Dad said.

“I had forgotten how her voice sounded, you know,” I replied. I don’t think I’d ever told him that.

He ended the conversation just as he’d ended every conversation about Mom.

“She was a good’un,” he said. “The best. The very best.”

Happy Thanksgiving.

Dig a Little Deeper

Go with The Bitter Southerner on an amazing journey through the annals of Southern gospel quartet music — including the single greatest quartet performance ever captured on video.